Paleo-Indians

| Paleo-Indians hunting a glyptodont Heinrich Harder (1858–1935), c.1920.  The Lithic peoples or Paleo-Indians are the earliest-known settlers of the Americas. The period's name derives from the appearance of "lithic flaked" stone tools. |

Paleo-Indians, Paleoindians or Paleo-Americans, were the first peoples who entered, and subsequently inhabited, the Americas during the final glacial episodes of the late Pleistocene period. The prefix "paleo-" comes from the Greek adjective palaios (παλαιός), meaning "old" or "ancient". The term "Paleo-Indians" applies specifically to the lithic period in the Western Hemisphere and is distinct from the term "Paleolithic".[1]

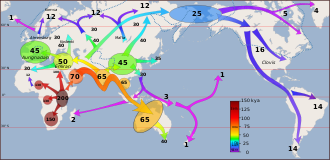

Traditional theories suggest that big-animal hunters crossed the Bering Strait from North Asia into the Americas over a land bridge (Beringia). This bridge existed from 45,000 to 12,000 BCE (47,000–14,000 BP).[2] Small isolated groups of hunter-gatherers migrated alongside herds of large herbivores far into Alaska. From c. 16,500 – c. 13,500 BCE (c. 18,500 – c. 15,500 BP), ice-free corridors developed along the Pacific coast and valleys of North America.[3] This allowed animals, followed by humans, to migrate south into the interior of the continent. The people went on foot or used boats along the coastline. The precise dates and routes of the peopling of the Americas remain subjects of ongoing debate.[4] At least two morphologically different Paleo-Indian populations were coexisting in different geographical areas of Mexico 10,000 years ago.[5]

Stone tools, particularly projectile points and scrapers, are the primary evidence of the earliest human activity in the Americas. Archaeologists and anthropologists use surviving crafted lithic flaked tools to classify cultural periods.[6] Scientific evidence links Indigenous Americans to eastern Siberian populations. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and genetic composition as indicated by molecular data, such as DNA.[7] There is evidence for at least two separate migrations.[8] From 8000 to 7000 BCE (10,000–9,000 BP) the climate stabilized, leading to a rise in population and lithic technology advances, resulting in a more sedentary lifestyle.

Migration into the Americas[]

Researchers continue to study and discuss the specifics of Paleo-Indian migration to and throughout the Americas, including the exact dates and routes traveled.[10] The traditional theory holds that these early migrants moved into Beringia between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska 17,000 years ago,[11] at a time when the Quaternary glaciation significantly lowered sea levels.[12] These people are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[13] An alternative proposed scenario involves migration - either on foot or using boats - down the Pacific coast to South America.[14] Evidence of the latter would since have been covered by a sea-level rise of more than a hundred meters following the end of the last glacial period.[15]

Archaeologists contend that Paleo-Indians migrated out of Beringia (western Alaska), between c. 40,000 and c. 16,500 years ago.[16][17][18] This time range remains a source of substantial debate. The few areas of agreement achieved to date are the origin from Central Asia, with widespread habitation of the Americas during the end of the last glacial period, or more specifically what is known as the late glacial maximum, around 16,000–13,000 years before present.[11][19] However, alternative theories about the origins of Paleoindians exist, including migration from Europe.[20]

Periodization[]

Sites in Alaska (East Beringia) are where some of the earliest evidence has been found of Paleo-Indians,[21][22][23] followed by archaeological sites in northern British Columbia, western Alberta and the Old Crow Flats region in the Yukon.[24] The Paleo-Indian would eventually flourish all over the Americas.[25] These peoples were spread over a wide geographical area; thus there were regional variations in lifestyles. However, all the individual groups shared a common style of stone tool production, making knapping styles and progress identifiable.[23] This early Paleo-Indian period's lithic reduction tool adaptations have been found across the Americas, utilized by highly mobile bands consisting of approximately 20 to 60 members of an extended family.[26][27] Food would have been plentiful during the few warm months of the year. Lakes and rivers were teeming with many species of fish, birds and aquatic mammals. Nuts, berries and edible roots could be found in the forests and marshes. The fall would have been a busy time because foodstuffs would have to be stored and clothing made ready for the winter. During the winter, coastal fishing groups moved inland to hunt and trap fresh food and furs.[28]

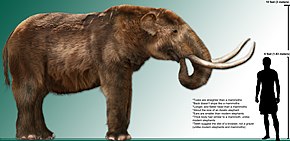

Late ice-age climatic changes caused plant communities and animal populations to change.[29] Groups moved from place to place as preferred resources were depleted and new supplies were sought.[25] Small bands utilized hunting and gathering during the spring and summer months, then broke into smaller direct family groups for the fall and winter. Family groups moved every 3–6 days, possibly traveling up to 360 km (220 mi) a year.[30][31] Diets were often sustaining and rich in protein due to successful hunting. Clothing was made from a variety of animal hides that were also used for shelter construction.[32] During much of the Early and Middle Paleo-Indian periods, inland bands are thought to have subsisted primarily through hunting now-extinct megafauna.[25] Large Pleistocene mammals were the giant beaver, steppe wisent, musk ox, mastodons, woolly mammoths and ancient reindeer (early caribou).[33]

The Clovis culture, appearing around 11,500 BCE (c. 13,500 BP),[34] undoubtedly did not rely exclusively on megafauna for subsistence.[35] Instead, they employed a mixed foraging strategy that included smaller terrestrial game, aquatic animals, and a variety of flora.[36] Paleo-Indian groups were efficient hunters and carried a variety of tools. These included highly efficient fluted-style spear points, as well as microblades used for butchering and hide processing.[37] Projectile points and hammerstones made from many sources are found traded or moved to new locations.[38] Stone tools were traded and/or left behind from North Dakota and Northwest Territories, to Montana and Wyoming.[39] Trade routes also have been found from the British Columbia Interior to the coast of California.[39]

The glaciers that covered the northern half of the continent began to gradually melt, exposing new land for occupation around 17,500–14,500 years ago.[29] At the same time as this was occurring, worldwide extinctions among the large mammals began. In North America, camelids and equids eventually died off, the latter not to reappear on the continent until the Spanish reintroduced the horse near the end of the 15th century CE.[40] As the Quaternary extinction event was happening, the Late Paleo-Indians would have relied more on other means of subsistence.[41]

From c. 10,500 – c. 9,500 BCE (c. 12,500 – c. 11,500 BP), the broad-spectrum big game hunters of the great plains began to focus on a single animal species: the bison (an early cousin of the American bison).[42] The earliest known of these bison-oriented hunting traditions is the Folsom tradition. Folsom peoples traveled in small family groups for most of the year, returning yearly to the same springs and other favored locations on higher ground.[43] There they would camp for a few days, perhaps erecting a temporary shelter, making and/or repairing some stone tools, or processing some meat, then moving on.[42] Paleo-Indians were not numerous and population densities were quite low.[44]

Classification[]

Paleo-Indians are generally classified by lithic reduction or lithic core "styles" and by regional adaptations.[23][45] Lithic technology fluted spear points, like other spear points, are collectively called projectile points. The projectiles are constructed from chipped stones that have a long groove called a "flute". The spear points would typically be made by chipping a single flake from each side of the point.[46] The point was then tied onto a spear of wood or bone. As the environment changed due to the ice age ending around 17–13Ka BP on short, and around 25–27Ka BP on the long,[47] many animals migrated overland to take advantage of the new sources of food. Humans following these animals, such as bison, mammoth and mastodon, thus gained the name big-game hunters.[48] Pacific coastal groups of the period would have relied on fishing as the prime source of sustenance.[49]

Archaeologists are piecing together evidence that the earliest human settlements in North America were thousands of years before the appearance of the current Paleo-Indian time frame (before the late glacial maximum 20,000-plus years ago).[50] Evidence indicates that people were living as far east as northern Yukon, in the glacier-free zone called Beringia before 30,000 BCE (32,000 BP).[51][52] Until recently, it was generally believed that the first Paleo-Indian people to arrive in North America belonged to the Clovis culture. This archaeological phase was named after the city of Clovis, New Mexico, where in 1936 unique Clovis points were found in situ at the site of Blackwater Draw, where they were directly associated with the bones of Pleistocene animals.[53]

Recent data from a series of archaeological sites throughout the Americas suggest that Clovis (thus the "Paleo-Indians") time range should be re-examined. In particular, sites located near in Idaho,[54] Cactus Hill in Virginia,[55] Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania,[56] Bear Spirit Mountain in West Virginia,[57] Catamarca and Salta in Argentina,[58] Pilauco and Monte Verde in Chile,[59][60] Topper in South Carolina,[61] and Quintana Roo in Mexico[62][63] have generated early dates for wide-ranging Paleo-Indian occupation. Some sites significantly predate the migration time frame of ice-free corridors, thus suggesting that there were additional coastal migration routes available, traversed either on foot and/or in boats.[64] Geological evidence suggests the Pacific coastal route was open for overland travel before 23,000 years ago and after 16,000 years ago.[65]

South America[]

In South America, the site of Monte Verde indicates that its population was probably territorial and resided in their river basin for most of the year. Some other South American groups, on the other hand, were highly mobile and hunted big-game animals such as mastodon and giant sloths. They used classic bifacial projectile point technology.

The primary examples are populations associated with El Jobo points (Venezuela), fish-tail or Magallanes points (various parts of the continent, but mainly the southern half), and Paijan points (Peru and Ecuador) at sites in grasslands, savanna plains, and patchy forests.[66]

The dating for these sites ranges from c. 14,000 BP (for Taima-Taima in Venezuela) to c. 10,000 BP.[67] The bi-pointed El Jobo projectile points were mostly distributed in north-western Venezuela; from the Gulf of Venezuela to the high mountains and valleys. The population using them were hunter-gatherers that seemed to remain within a certain circumscribed territory.[68][69] El Jobo points were probably the earliest, going back to c. 14,200 – c. 12,980 BP and they were used for hunting large mammals.[70] In contrast, the fish-tail points, dating to c. 11,000 B.P. in Patagonia, had a much wider geographical distribution, but mostly in the central and southern part of the continent.[71][72]

Archaeogenetics[]

The haplogroup most commonly associated with indigenous Amerindian genetics is Haplogroup Q-M3.[73] Y-DNA, like (mtDNA), differs from other nuclear chromosomes in that the majority of the Y chromosome is unique and does not recombine during meiosis. This allows the historical pattern of mutations to be easily studied.[74] The pattern indicates Indigenous Amerindians experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes: first with the initial peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonization of the Americas.[75] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous Amerindian populations.[76]

Human settlement of the Americas occurred in stages from the Bering sea coast line, with an initial layover on Beringia for the founding population.[77][78][79][80] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[81] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations, however, exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations that are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA mutations.[82][83][84] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.[85]

Transition to archaic period[]

The Archaic period in the Americas saw a changing environment featuring a warmer, more arid climate and the disappearance of the last megafauna.[86] The majority of population groups at this time were still highly mobile hunter-gatherers, but now individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally. Thus with the passage of time there is a pattern of increasing regional generalization like the Southwest, Arctic, Poverty, Dalton, and Plano traditions. These regional adaptations would become the norm, with reliance less on hunting and gathering, and a more mixed economy of small game, fish, seasonally wild vegetables, and harvested plant foods.[31][87] Many groups continued to hunt big game but their hunting traditions became more varied and meat procurement methods more sophisticated.[29] The placement of artifacts and materials within an Archaic burial site indicated social differentiation based upon status in some groups.[88]

See also[]

- Adams County Paleo-Indian District – (Archeological site)

- Arlington Springs Man – (Human remains)

- Blackwater Draw – (Archeological site)

- Borax Lake Site – (Archeological site)

- Buhl woman – (Human remains)

- Calico Early Man Site – (Archeological site)

- Caverna da Pedra Pintada – (Archeological site)

- Cody complex – (Culture group)

- Cueva de las Manos – (Cave paintings)

- East Fork Site – (Archeological site)

- Fort Rock Cave – (Archeological site)

- Hiscock Site – (Archeological site)

- Kennewick Man – (Human remains)

- Lehner Mammoth-Kill Site – (Archeological site)

- Lindenmeier Site – (Archeological site)

- Luzia Woman – (Human remains)

- Marmes Rockshelter – (Archeological site)

- Mastodon State Historic Site – (Archeological site)

- Mummy Cave – (Archeological site)

- Naia – (Human remains)

- Paisley Caves – (Archeological site)

- Peñon woman – (Human remains)

- Post Pattern – (Archaeological culture)

- San Dieguito Complex – (Archeological site)

- Sandia Man Cave – (Archeological site)

- Upward Sun River site – (Archeological site)

- Witt Site – (Archeological site)

- X̲áːytem – (Archeological site)

- Quad Site – (Archeological site)

![]() Indigenous peoples of the Americas portal

Indigenous peoples of the Americas portal

References[]

- ^ Paleolithic specifically refers to the period between c. 2.5 million years ago and the end of the Pleistocene in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is not used in New World archaeology.

- ^ Liz Sonneborn (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover – Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

Archaeological evidence, in fact, recognizes that people started to leave Beringia for the New World around 40,000 years ago, but rapid expansion into North America didn't occur until about 15,000 years ago, when the ice had literally broken

page 2 Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine - ^ H. Trawick Ward; R. P. Stephen Davis (1999). Time before history: the archaeology of North Carolina. UNC Press Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8078-4780-0. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "10,000-year-old skeleton challenges theory of how humans arrived in Americas". The Independent. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Method and Theory in American Archaeology". Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips. University of Chicago. 1958. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Patricia J. Ash; David J. Robinson (2011). The Emergence of Humans: An Exploration of the Evolutionary Timeline. John Wiley & Sons. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-119-96424-7.

- ^ Pitblado, B. L. (2011-03-12). "A Tale of Two Migrations: Reconciling Recent Biological and Archaeological Evidence for the Pleistocene Peopling of the Americas". Journal of Archaeological Research. 19 (4): 327–375. doi:10.1007/s10814-011-9049-y. S2CID 144261387.

- ^ Burenhult, Göran (2000). Die ersten Menschen. Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8289-0741-6.

- ^ Phillip M. White (2006). American Indian chronology: chronologies of the American mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-33820-5. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford, Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Fladmark, K. R. (Jan 1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189.

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-04-24. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago as at U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ^ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- ^ "Journey of mankind". Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Bonatto, SL; Salzano, FM (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". PNAS. 94 (5): 1866–71. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1866B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- ^ Neves, W. A.; Powell, J. F.; Prous, A.; Ozolins, E. G.; Blum, M. (1999). "Lapa vermelha IV Hominid 1: morphological affinities of the earliest known American". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 22 (4): 461. doi:10.1590/S1415-47571999000400001.

- ^ Bruce Elliott Johansen; Barry Pritzker (2008). Encyclopedia of American Indian history. ABC-CLIO. pp. 451–. ISBN 978-1-85109-817-0. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Period 1 (10,000 to 8,000 years ago)". Learners Portal Breton University. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wm. Jack Hranicky; Wm Jack Hranicky Rpa (17 June 2010). North American Projectile Points - Revised. AuthorHouse. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4520-2632-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Norman Herz; Ervan G. Garrison (1998). Geological methods for archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-509024-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Barry Lewis; Robert Jurmain; Lynn Kilgore (10 December 2008). Understanding Humans: Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Archaeology. Cengage Learning. pp. 342–348. ISBN 978-0-495-60474-7. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ David J. Wishart (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. U of Nebraska Press. p. 589. ISBN 978-0-8032-4787-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Rickey Butch Walker (December 2008). Warrior Mountains Indian Heritage - Teacher's Edition. Heart of Dixie Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-934610-27-5. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Dawn Elaine Bastian; Judy K. Mitchell (2004). Handbook of Native American mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-85109-533-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pielou, E.C. (1991). After the Ice Age : The Return of Life to Glaciated North America (Digitised online by Google books). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66812-3. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ David R. Starbuck (31 May 2006). The archeology of New Hampshire: exploring 10,000 years in the Granite State. UPNE. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58465-562-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fiedel, Stuart J (1992). Prehistory of the Americas (Digitised online by Google books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42544-5. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ "Alabama Archaeology: Prehistoric Alabama". University of Alabama Press. 1999. Archived from the original on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ Breitburg, Emanual; John B. Broster; Arthur L. Reesman; Richard G. Strearns (1996). "Coats-Hines Site: Tennessee's First Paleoindian Mastodon Association" (PDF). Current Research in the Pleistocene. 13: 6–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ Catherine Anne Cavanaugh; Michael Payne; Donald Grant Wetherell (2006). Alberta formed, Alberta transformed. University of Alberta. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-55238-194-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ McMenamin, M. A. S. (2011). "A recycled small Cumberland-Barnes Palaeoindian biface projectile point from southeastern Connecticut". Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 72 (2): 70–73.

- ^ Scott C. Zeman (2002). Chronology of the American West: from 23,000 B.C.E. through the twentieth century. ABC-CLIO. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-57607-207-3. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ William C. Sturtevant (21 February 1985). Handbook of North American Indians. Government Printing Office. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-16-004580-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Emory Dean Keoke; Kay Marie Porterfield (January 2005). Trade, Transportation, and Warfare. Infobase Publishing. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-8160-5395-7. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brantingham, P. Jeffrey; Kuhn, Steven L.; Kerry, Kristopher W. (2004). The Early Upper Paleolithic beyond Western Europe. University of California Press. pp. 41–66. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ "A brief history of the horse in America: Horse phylogeny and evolution". Ben Singer. Canadian Geographic. 2005. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ Anderson, David G; Sassaman, Kenneth E (1996). The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast (Digitised online by Google books). University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0835-3. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mann, Charles C. (2006-10-10). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (Digitised online by Google books). Random House of Canada. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Folsom Traditions". University of Manitoba, Archaeological Society. 1998. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ "Beginnings to 1500 C.E". Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. Archived from the original on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Vance T. Holliday (1997). Paleoindian geoarchaeology of the southern High Plains. University of Texas Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-292-73114-1. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Adovasio, J. M., J.M. (2002). The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology's Greatest Mystery. with Jake Page. New York: Random House. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-375-50552-2.

- ^ Wolfgang H. Berger; Elizabeth Noble Shor (25 April 2009). Ocean: reflections on a century of exploration. University of California Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-520-24778-9. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ McHugh, Tom; Hobson, Victoria (1979). The Time of the Buffalo. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8105-9. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ deFrance, Susan D.; Keefer, David K.; Richardson, James B.; Alvarez, Adan U. (2010). "Late Paleo-Indian Coastal Foragers: Specialized Extractive". Latin American Antiquity. 12 (4): 413–426. doi:10.2307/972087. JSTOR 972087. S2CID 163802845.

- ^ "Alberta History pre 1800 - Jasper Alberta". Jasper Alberta. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Bradley, B. and Stanford, D. "The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World." World Archaeology 34, 2004.

- ^ Lauber, Patricia. Who Came First? New Clues to Prehistoric Americans. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2003.

- ^ "National Park Service Southeastern Archaeological Center: The Paleoindian Period". Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (2019-08-29). "First people in the Americas came by sea, ancient tools unearthed by Idaho river suggest". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ "Science News Online: Early New World Settlers Rise in East". Science News. 2000. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Meadowcroft Rockshelter". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Author Discovers Ceremonial Site". Archaeology Site Article listing. Herald Mall Media. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ "Encontraron la evidencia humana más antigua de Argentina".

- ^ https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/2019/04/27/confirman-huella-humana-en-chile-como-la-mas-antigua-de-america-4987.html

- ^ "Monte Verde Archaeological Site - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "CNN.com: Man in Americas Earlier Than Thought". 2004-11-18. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Ignacio Villarreal (2010-08-25). "Mexican Archaeologists Extract 10,000 Year-Old Skeleton from Flooded Cave in Quintana Roo". Artdaily.com. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ "Skull in Underwater Cave May Be Earliest Trace of First Americans - NatGeo News Watch". Blogs.nationalgeographic.com. 2011-02-18. Archived from the original on 2011-02-26. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ "Does skull prove that the first Americans came from Europe?". The University of Texas at Austin - Web Central. Archived from the original on 2004-03-02. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Jordan, David K (2009). "Prehistoric Beringia". University of California-San Diego. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ TOM D. DILLEHAY, The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America. Evolutionary Anthropology, 1999

- ^ Cummings, Vicki; Jordan, Peter; Zvelebil, Marek (2014). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers. OUP Oxford. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-19-102526-6.

- ^ José R. Oliver, Implications of Taima-taima and the Peopling of Northern South America. Archived 2016-04-25 at the Wayback Machine bradshawfoundation.com

- ^ Oliver, J.R., Alexander, C.S. (2003). Ocupaciones humanas del Plesitoceno terminal en el Occidente de Venezuela. Maguare, 17 83-246

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-387-75228-0.

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-75228-0.

- ^ Dillehay, Thomas D. (2008). The Settlement of the Americas. Basic Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7867-2543-4.

- ^ "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas" (PDF). University College London 73:524–539. 2003. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Orgel L (2004). "Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world" (PDF). Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 39 (2): 99–123. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.537.7679. doi:10.1080/10409230490460765. PMID 15217990. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ Wendy Tymchuk, ed. (2008). "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. Archived from the original (Verbal tutorial possible) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Wendy Tymchuk, ed. (2008). "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. Archived from the original (Verbal tutorial possible) on 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2009-11-21.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Alice Roberts (2010). The Incredible Human Journey. A&C Black. pp. 101–03. ISBN 978-1-4088-1091-0.

- ^ "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover - Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Archived from the original on 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2009-11-18. page 2 Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pause Is Seen in a Continent's Peopling". The New York Times. 13 Mar 2014.

- ^ Than, Ker (2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ^ "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ Ruhlen M (November 1998). "The origin of the Na-Dene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (23): 13994–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513994R. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13994. PMC 25007. PMID 9811914.

- ^ Zegura SL, Karafet TM, Zhivotovsky LA, Hammer MF (January 2004). "High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single, recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (1): 164–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- ^ Saillard, Juliette; Forster, Peter; Lynnerup, Niels; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Nørby, Søren (2000). "mtDNA Variation among Greenland Eskimos. The Edge of the Beringian Expansion". Laboratory of Biological Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, University of Hamburg, Hamburg. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ^ Torroni, A.; Schurr, T. G.; Yang, C. C.; Szathmary, E.; Williams, R. C.; Schanfield, M. S.; Troup, G. A.; Knowler, W. C.; Lawrence, D. N.; Weiss, K. M.; Wallace, D. C. (January 1992). "Native American Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Indicates That the Amerind and the Nadene Populations Were Founded by Two Independent Migrations". Center for Genetics and Molecular Medicine and Departments of Biochemistry and Anthropology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Genetics Society of America. 1992. Vol 130, 153-162. 130 (1): 153–162. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ^ Douglas Ian Campbell; Patrick Michael Whittle (2017). Resurrecting Extinct Species: Ethics and Authenticity. Springer. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-3-319-69578-5.

- ^ Stuart B. Schwartz, Frank Salomon (1999-12-28). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas (Digitised online by Google books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63075-7. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Imbrie, J; K.P.Imbrie (1979). Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery. Short Hills NJ: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 978-0-226-66811-6.

Further reading[]

- Jablonski, Nina G (2002). The First Americans: The Pleistocene Colonization of the New World. California Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-940228-49-8.

- Peter Charles Hoffer (2006). The Brave New World: A History of Early America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8483-2.

- Meltzer, David J (2009). First peoples in a new world: colonizing ice age America. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-0-520-25052-9.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lithic period. |

- Atlas of the Human Journey, Genographic Project, National Geographic

- Journey of Mankind - Genetic Map - Bradshaw Foundation

- The Paleoindian Period - United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service

- Alabama Archaeology: Prehistoric Alabama - The University of Alabama, Department of Archaeology

- The Paleoindian Database - The University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology.

- Paleoindians and the Great Pleistocene Die-Off - American Academy of Arts and Sciences, National Humanities Center

- Paleo-Indian period

- Pre-Columbian cultures

- Archaeological cultures of North America

- Archaeological cultures of South America

- History of indigenous peoples of North America

- History of Indigenous peoples in Canada

- Native American history

- History of the Americas

- History of North America

- History of South America

- Hunter-gatherers

- Hunter-gatherers of the United States

- Hunter-gatherers of Canada

- Hunter-gatherers of South America

- Late Pleistocene

- Mesoamerica

- Pleistocene life

- Pleistocene North America

- Pleistocene South America

- Pre-Columbian archaeology