Paraskeva Friday

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (November 2021) |

The embodiment of the day of the week is Friday. The saint is considered by the Eastern Slavs as the healer of mental and bodily ailments, the guardian of family well-being and happiness. The saint is commemorated {

| |||

| Folklore | Slavic Mythology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Paraskeva Friday - In popular tradition of the mythologized an image based on personification of Friday as the day of the week and the cult of saints Paraskeva of Iconium, called Friday and Paraskeva of Serbia.[1] According to a number of researchers, on Paraskeva Friday were transferred some signs and functions of the main female character Slavic mythology - Mokosh, whose image is associated with female works (spinning, sewing, etc.), with marriage and childbearing, with the earthly moisture.[2] In folk tradition, the image of Paraskeva Friday also correlated with the image of Goddess, Saint Anastasia of the Lady of Sorrows, and the Week as personified image of Sunday.[1]

Etymology[]

The word "paraskeva" (Greek: παρασκευη paraskeue) means "preparation [for the Sabbath]; preparation. Thus, Paraskeva Friday is preparation for the Sabbath; the day of the sixth; a semi-holiday. In Evangelion John 19.31 "'But since then it was Friday' (paraskeva)..."

Representations of the Eastern Slavs[]

In East Slavs, Paraskeva Friday is a personified representation of day of the week.[3] Otherwise, she was called Linyanitsa, other nicknames were Paraskeva Pyatnitsa, Paraskeva Lyanyanikha, Nenila Linyanitsa. Paraskeva Friday was dedicated 27 [O.S. ] October - Paraskeva Muddyha Day and [O.S. ] 10 November - Day of Paraskeva the Flaxwoman. In the church, these days commemorate Paraskeva of Srpska and Paraskeva of Iconium, respectively. On these days, no spinning, washing, or plowing was done so as not to "dust the Paraskeva or to clog her eyes." It was believed that in the case of violation of the ban, she could inflict disease. One of the decrees of the [Stoglav Synod] (1551) is devoted to condemnation of such Superstition superstitions:

Yes, by pogosts and by the villages walk false prophets, men and wives, and maidens, and old women, naked and barefoot, and with their hair straight and loose, shaking and being killed. And they say that they are Saint Friday and Saint Anastasia and that they command them to command the canons of the church. They also command the peasants in and in Friday not to do manual labor, and to wives not to spin, and not to wash clothes, and not to kindle stones.[4][5]

The echo of Slavic pre-Christian beliefs some authors consider preserved in some places in the XIX - early XX centuries " idols" sculptural images of saints. The most common was the sculpture of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa - and not only in Russian, but also in the neighboring peoples.[5] Previously, in the chapels in foreign areas "there were images made of wood rough work of St. Paraskeva and Nicholas... All carved images of Saints Paraskeva and Nicholas have the common name of Pyatnits".[6] In the Russians were widespread sculptures - "wooden painted statue of Pyatnitsa, sometimes in the form of a woman in oriental dress, and sometimes in the form of a simple woman in paneve and lapti". The statue of Paraskeva "was placed in churches in special cabinets and people prayed before this idol".[7]

In the eastern Slavs wooden sculptures of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa were also placed on wells, to her were brought sacrifices (in the well threw cloths, kudel, threads, sheep's wool). The rite was called mokrida (cf. Mokosh).

Silver hryvnias and quintuplets at the bottom of wells... various articles of women's free will were handed over or thrown directly, often with a loud declaration of the direct purpose of the donation: sewn linen as shirts, towels to decorate the corolla and countenance, combed out linen hemp or straightened ready threads, and wool (sheep's wool) ("To the Weasel for chulovki! ", "To Mother Friday for an apron!" - the women shout on such occasions).

- C. V. Maximov[8]

In ancient times, in honor of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa, special columns with a picture of the saint were placed at crossroads and on roads that were named after her. These monuments were like roadside chapels or crosses and were considered sacred places.[9]

The Russians prayed to Paraskeva Pyatnitsa for protection against the death of livestock, especially cows. The saint was also considered the healer of human ailments, especially devil's obsession, fever, toothache, headache, and other ailments.

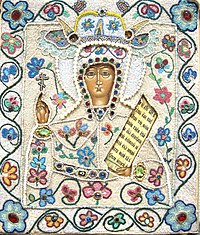

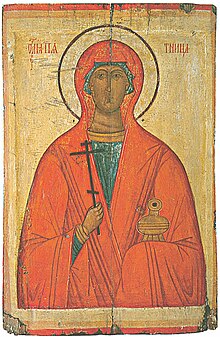

Image[]

The image of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa according to folk beliefs is markedly different from the iconographic image, where she is depicted as an ascetic-looking woman in a red maforiya. The carved icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa from the village of Illyeshi is widely known. It is revered in the Russian Orthodox Church as a miracle worker and is housed in the Trinity Cathedral of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg.[10]

The popular imagination sometimes gave Paraskeva Friday demonic features: tall stature, long loose hair, large breasts, which she throws behind her back, etc., which brings her closer to the female mythological characters like Dola, Death, Mermaid. There was a ritual of "driving Pyatnitsa" documented in the 18th century: "In Small Russia, in the Starodubsky regiment on a holiday day they drive a plain-haired woman named Pyatnitsa, and they drive her in the church and at church people honor her with gifts and with the hope of some benefit".[11] In the stories Paraskeva Pyatnitsa spins the kudel left by the mistress (like home, kimora, mare),[12] punishes the woman who dared in spite of the ban on spinning, thread winding, sewing: tangles the thread, may skin the offending woman, take away her eyesight, turn her into a frog, throw forty spindles into the window with orders to strain them until morning, etc. [13]

According to beliefs, Paraskeva Friday also controls the observance of other Friday prohibitions (washing laundry, bleaching canvases, combing hair, etc.)[14]

According to Ukrainian beliefs, Friday walks pierced with needles and spindles of negligent hosts who have not honored the saint and her days. Until the 19th century, the custom of "leading Pyatnitsa" - a woman with loose hair{[15] was preserved in Ukraine.

In bylichki and spiritual verses Paraskeva Pyatnitsa complains that she is not honored by not observing the Friday prohibitions - they prick her with spindles, spin her hair, clog her eyes kostra. According to beliefs, the icons depict Paraskeva Friday with spokes or spindles sticking out of her chest (cf. images of Our Lady of the Seven Spears or Softening of the Evil Hearts).[1]

In the folk calendar[]

[O.S. October] 27 is celebrated everywhere by South Slavs: Bulgarian: Petkovden, St. Petka, Petka, Pejcinden, Macedonian: Petkovden, Serbian: Petkovica, Petkovaca, Sveta Paraskeva, Sveta Petka, Pejcindan, etc. Some regions of Serbia and Bosnia also celebrate 8 August [O.S. ], called Petka Trnovska, Petka Trnovka, Trnovka Petka, Mlada Petka, Petka Vodonosha. In Bulgaria (Frakia), St. Petka is dedicated to the Friday after Easter (Bulgarian: Latna St. Petka, Presveta Petka, Petka Balklia), and in Serbia (Požega) the Friday before St. Evdokija Day (14 [O.S. ] March)[16]

Ninth Friday[]

The celebration of the ninth Friday after Easter was widespread among Russians. In Solikamsk, the miraculous deliverance of the city from the invasion of Nogais and voguls in 1547 was remembered on this day.[17]

In Nikolsky County Vologda province] on the ninth Friday there was a custom to "build a customary linen": the girls would come together, rub the flax, spin and weave the linen in a day{.[5]

At Komi people, living along the river Vashke, the ninth Friday was called the "Covenant Day of the Sick" (Komi: Zavetnoy lun vysysyaslӧn). It was believed that on this day the miracle-working icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (Komi: Paraskeva-Peknicha from the chapel in the village of Krivoy Navolok could bring healing to the sick. There is still a tradition of crosswalks to the Ker-yu river, where elderly women and girls wash temple and home icons in the waters blessed with the icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa. The water is considered holy for three days after the feast, and it is collected and taken away with them. Dipping icons in standing water is considered a sin.

Sayings and Prohibitions[]

- On Friday, Mother Praskovia, it is sinful to disturb the earth, for there was an earthquake[5] at the time of the Savior's death on the cross.

- Whoever spins on Friday, his father and mother will be blind in the next world{.[5]

- Women were not allowed to scratch or wash their hair on Friday.[5]

- Men don't plow on Fridays, women don't spin.[18]

- Polish: Co piątek, to świątek [19]

- Squinting like Wednesday on Friday (Ukrainian: Squinting yak sreda na p'yatnitsya)[20]

See Also[]

References[]

- ^ a b c Levkievskaya, Tolstaya 2009.

- ^ Levkievskaya, Thick 2009.

- ^ Kruk, Kotovich 2003.

- ^ Chicherov, 1957, p.

- ^ a b c d e f Chicherov 1957.

- ^ Mozharovsky 1903.

- ^ Svyatsky 1908.

- ^ Maksimov, 1903, pp. 232-233.

- ^ Kalinsky 2008.

- ^

Старцева Ю. В.,

Старцева Ю. В.,  Попов И. В. (2001). "Явление вмц. Параскевы Пятницы в Ильешах" (PDF) (Журнал) (25) (Санкт-Петербургские Епархиальные ведомости ed.): 91–96.

Попов И. В. (2001). "Явление вмц. Параскевы Пятницы в Ильешах" (PDF) (Журнал) (25) (Санкт-Петербургские Епархиальные ведомости ed.): 91–96. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lavrov 2000.

- ^ Levkievskaya, Fat 2009.

- ^ Madlevskaya et al. 2007.

- ^ Szczepanska 2003.

- ^ Voropay 1958.

- ^ Levkija, Thick 2009.

- ^ "The Ninth Friday after Easter in Solikamsk". Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Dal & 1880-1882.

- ^ Ermolov 1905.

- ^ Vakulenko et al. 1994.

Literature[]

- Пять // Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка : в 4 т. / авт.-сост. В. И. Даль. — 2-е изд. — СПб. : Типография М. О. Вольфа, 1880—1882.

- Параскева Пятница / Левкиевская Е. Е., Толстая С. М. // Славянские древности: Этнолингвистический словарь : в 5 т. / под общ. ред. Н. И. Толстого; ru:Институт славяноведения РАН. — М. : Межд. отношения, 2009. — Т. 4: П (Переправа через воду) — С (Сито). — С. 631—633. — ISBN 5-7133-0703-4, 978-5-7133-1312-8.

- Максимов С. В. Параскева Пятница; Вода-Царица // Нечистая, неведомая и крестная сила. — СПб.: Товарищество Р. Голике и А. Вильворг, 1903. — С. 516—518, 225—250.

- Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

Links[]

- Параскева Пятница (hrono.ru)

- Параскева // Российский этнографический музей

- Пятница // Энциклопедия культур

- Успенский Б. А. Почитание Пятницы и Недели в связи с культом Мокоши // Успенский Б. А. Филологические разыскания в области славянских древностей

- Рыбаков Б. А. Двоеверие. Языческие обряды и празднества XI—XIII веков // Рыбаков Б. А. Язычество Древней Руси

- Страсти по Святой Параскеве (dralexmd.livejournal.com)

- Basil Lourié. Friday Veneration in the Sixth- and Seventh-Century Christianity and the Christian Legends on Conversion of Nağrān (англ.)

- Folk Christianity

- Slavic legendary creatures

- Friday