Pectodens

| Pectodens Temporal range: Anisian,

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Dinocephalosauridae |

| Genus: | †Pectodens Li et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| Pectodens zhenyuensis Li et al., 2017

| |

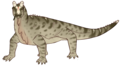

Pectodens (meaning "comb tooth") is an extinct genus of archosauromorph reptile which lived during the Middle Triassic in China. The type and only species of the genus is P. zhenyuensis, named by Chun Li and colleagues in 2017. It may be a member of the Protorosauria; an unusual combination of traits similar (such as the long neck) and dissimilar (such as the absence of a hook on the fifth metatarsal bone) to other members causes Pectodens to elude exact classification.

A small, slender animal measuring 38 centimetres (15 in) long, Pectodens was named after the peculiar comb-like arrangement of long, conical teeth present in its mouth. Unlike Dinocephalosaurus and the other reptiles that it was preserved with, well-developed joints and claw-like digits indicate that Pectodens was entirely terrestrial. However, its presence in marine deposits suggests that lived relatively close to the coastline.

Description[]

Pectodens is a small animal with a slender build, measuring roughly 38 centimetres (15 in) long. The skull measures 25.7 mm (1.01 in) long, while the lower jaw was probably 25–26 mm (0.98–1.02 in) long when complete. Uniquely, numerous conical teeth in the jaws of Pectodens form a comb-like structure. These teeth have weakly-developed broad enamel ridges. There are 10 teeth in each premaxilla at the front of the jaw, and at least 24 more on the maxilla further back. There are also teeth on the palate, with at least 15 being present on the pterygoid bone. Additionally, the eye socket is very large, measuring 10.5 mm (0.41 in) long, although this may be due to the animal's immaturity. Meanwhile, the rear (temporal) region of the skull is quite short.[1]

The neck and tail of Pectodens were long, with the former being the same length as the torso. In life, it had 66 to 68 vertebrae, with 11-12 cervical vertebrae, 11-13 dorsal vertebrae, 2 sacral vertebrae, and 41 caudal vertebrae in the tail. The cervicals have low neural spines, like Tanystropheus. The cervical ribs are generally also long, having short forward processes and long rear processes that bridge two to three vertebral joints each. Meanwhile, the transverse processes of the dorsals are characteristically long and pronounced, terminating in sub-circular facet joints for the rounded heads of the ribs. Also like Tanystropheus, the transverse processes of the tail become gradually reduced alongside the forward processes of the chevrons, disappearing by the 35th caudal vertebra.[1]

Like Tanystropheus and Macrocnemus, the scapula is low.[2] The long bones of the forelimbs have expanded and robust top ends; the deltopectoral crest on the humerus is also rather prominent. The humerus is longer than the ulna and radius, while the tibia and fibula are conversely slightly longer than the femur. An empty gap in the wrist suggests that not all of the wrist bones were ossified; the distal tarsals also appear to be missing from the ankle, but the remaining bones articulate directly with the foot. Unusually, there is no "hook" on the fifth metatarsal bone, unlike Tanystropheus. The hands and feet each have five digits, with the five digits respectively having 2, 3, 4, 5, and 4 phalanges (although there may only be 3 in the fifth digits of the hands).[1]

Discovery and naming[]

Pectodens is known from one specimen, consisting of a well-preserved and almost complete skeleton. The fossil is preserved on two separate blocks that broke cleanly, but details of the pelvis were lost in the process. Additionally, the left femur is missing, as is part of one cervical. The specimen is catalogued as IVPP V18578, being stored in the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China. It was described by Chun Li, Nicholas Fraser, Olivier Rieppel, Li-Jun Zhao, and Li-Ting Wang in a 2017 research paper published in the Journal of Paleontology.[1]

The specimen itself was found in Luoping County in Yunnan, China. It is part of the "Panxian-Luoping fauna", a faunal assemblage which is part of Member II of the Anisian (Middle Triassic) Guanling Formation. Conodont biostratigraphy (based on the presence of )[3] and radiometric dating[4] have dated the assemblage in Luoping to 244 million years old. Predominant deposits in Member II of the Guanling Formation consist of grey layers of marly limestone and limestone.[1][5]

In their 2017 description of IVPP V18578, Li and colleagues named the new genus Pectodens, from Latin pecto- ("comb") and dens ("tooth"), in reference to the animal's characteristic comb-like arrangement of elongated teeth. They also named the type species Pectodens zhenyuensis after Zhenyu Li, who had assisted with the collection of the specimen.[1]

Classification[]

The classification of Pectodens is complicated by the presence of both characteristics similar to the Protorosauria as well as characteristics which would be expected in more basal archosauromorphs. Like Tanystropheus, Macrocnemus, and other protorosaurs, the cervicals are long with low neural spines, and bear cervical ribs that bridge multiple joints.[6][7][8] These same characteristics previously allowed Li, Fraser, and Rieppel to assign Dinocephalosaurus to the Protorosauria.[9] Yet, in Pectodens, the puboischiadic plate (formed from the pubis and ischium) does not appear to bear a perforation known as the thyroid fenestra, the astragalus and calcaneum of the ankle are simple and rounded, and the fifth metatarsal is not hooked.[1]

Poor preservation in some regions also hampered the classification of Pectodens. The blocks containing the type specimen had split through the puboischiadic plate, for instance; the neural spines of the dorsals are also not visible, which means that they cannot be compared with those of the Tanystropheidae (which are tall and elongated). Also related is the uncertainty in the number of phalanges in the fifth digit of the hand; most protorosaurs have three, while Pectodens may have three or four depending on whether a breakage is interpreted as obscuring one single phalanx or two overlapping phalanges. Considering all of this uncertainty, Li and colleagues thus tentatively considered Pectodens a protorosaur.[1]

Paleobiology[]

Judging by the slender limbs with robust joints and claw-tipped elongate digits, Pectodens was most likely an entirely terrestrial animal. It exhibits no adaptations for an aquatic lifestyle, unlike other archosauromorphs in the Panxian-Luoping biota (the amphibious Qianosuchus, for instance, or the marine Dinocephalosaurus).[1]

Paleoecology[]

Pectodens on the land surrounding a shallow sea that covered much of southern China during the Middle Triassic. Four major landmasses were present in this region, which had been formed by a mountain-building event known as the Indosinian orogeny: Khamdian to the west, Jiangnan occupying a central position, Yunkai to the south, and Cathaysia to the east. The Lagerstätten of Panxian and Luoping were laid down as fossil-bearing sediments on the western edge of an oceanic basin located between Khamdian and Jiangnan, known as the Nanpanjiang Basin.[5][10][11][12] All of these geological features are part of the South China Block, a tectonic plate presently composed of the Yangtze Craton and the South China Fold Belt.[10][13]

Although Pectodens was fully terrestrial, it was preserved alongside the other fauna of Luoping within a small oceanic intraplatform basin, in which preservation was facilitated by the presence of anoxic sediments. Reptiles, including Dinocephalosaurus alongside Mixosaurus cf. panxianensis, Dianopachysaurus dingi, Sinosaurosphargis yunguiensis, and an archosaur,[5] constitute the minority of fossils, constituting 0.07% of 19,759 specimens found at Luoping.[14] By comparison, 93.7% of Luoping's fossils are arthropods, including decapods, isopods, cycloids, mysidaceans, clam shrimp, ostracods, millipedes, and horseshoe crabs. Fish consist of 25 taxa in 9 families and form 3.66% of fossil specimens, including saurichthyids, palaeoniscids, birgeriids, perleidids, eugnathids, semionotids, pholidopleurids, peltopleurids, and coelacanths. Molluscs, including bivalves and gastropods account for 1.69% alongside ammonoids and belemnoids. Echinoderms such as crinoids, starfish, and sea urchins, as well as branchiopods, are rare, and probably did not originate from local waters. Branches and leaves from conifers have also been found, representing coastal forests located less than 10 km (6.2 mi) away from the intraplatform basin.[14] The proximity of the shoreline to this basin is supported by the occurrence of Pectodens.[1]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Li, C.; Fraser, N.C.; Rieppel, O.; Zhao, L.-J.; Wang, L.-T. (2017). "A new diapsid from the Middle Triassic of southern China" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 91 (6): 1306–1312. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.12.

- ^ Nosotti, S. "Tanystropheus longobardicus (Reptilia, Protorosauria): re-interpretations of the anatomy based on new specimens from the Middle Triassic of Besano (Lombardy, northern Italy)". Memorie della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano. 35 (3): 1–88.

- ^ Zhang, Q.-Y.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Lu, T.; Xie, T.; Lou, X.-Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Zhao, L.-S. (2009). "A conodont-based Middle Triassic age assignment for the Luoping Biota of Yunnan, China". Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences. 52 (10): 1673–1678. Bibcode:2009ScChD..52.1673Z. doi:10.1007/s11430-009-0114-z. S2CID 129857181.

- ^ Liu, J.; Organ, C.L.; Benton, M.J.; Brandley, M.C.; Aitchison, J.C. (2017). "Live birth in an archosauromorph reptile". Nature Communications. 8: 14445. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814445L. doi:10.1038/ncomms14445. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5316873. PMID 28195584.

- ^ a b c Benton, M.J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, S.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Wen, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, C.; Xie, T.; Tong, J.; Choo, B. (2013). "Exceptional vertebrate biotas from the Triassic of China, and the expansion of marine ecosystems after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction". Earth-Science Reviews. 123: 199–243. Bibcode:2013ESRv..125..199B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.05.014.

- ^ Jalil, N.-E. (1997). "A new prolacertiform diapsid from the Triassic of North Africa and the interrelationships of the Prolacertiformes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (3): 506–525. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010998.

- ^ Benton, M.J.; Allen, J.L. (1997). "Boreopricea from the Lower Triassic of Russia, and the relationships of the prolacertiform reptiles". Palaeontology. 40: 931–953.

- ^ Evans, S.E. (1998). "The early history and relationships of the Diapsida". In Benton, M.J. (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 221–253.

- ^ Rieppel, O.; Li, C.; Fraser, N.C. (2008). "The Skeletal Anatomy of the Triassic Protorosaur Dinocephalosaurus orientalis Li, from the Middle Triassic of Guizhou Province, Southern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[95:TSAOTT]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 30126337.

- ^ a b Lehrmann, D.J.; Minzoni, M.; Enos, P.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Wei, J.-Y.; Li, R.-X. (2009). "Triassic depositional history of the Yangtze platform and Great Bank of Guizhou in the Nanpanjiang basin of South China". Journal of Earth Sciences and Environment. 31 (4): 344–367.

- ^ Lehrmann, D.J.; Payne, J.L.; Felix, S.V.; Dillett, P.M.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Wei, J. (2003). "Permian–Triassic Boundary Sections from Shallow-Marine Carbonate Platforms of the Nanpanjiang Basin, South China: Implications for Oceanic Conditions Associated with the End-Permian Extinction and Its Aftermath". PALAIOS. 18 (2): 138–152. Bibcode:2003Palai..18..138L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.1486. doi:10.1669/0883-1351(2003)18<138:PBSFSC>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Lehrmann, D.J.; Payne, J.L.; Pei, D.; Enos, P.; Druke, D.; Steffen, K.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Orchard, M.J.; Ellwood, B. (2007). "Record of the end-Permian extinction and Triassic biotic recovery in the Chongzuo-Pingguo platform, southern Nanpanjiang basin, Guangxi, South China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (1): 200–217. Bibcode:2007PPP...252..200L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.044.

- ^ Lehrmann, D.J.; Enos, P.; Payne, J.L.; Montgomery, P.; Wei, J.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Orchard, M.J. (2005). "Permian and Triassic depositional history of the Yangtze platform and Great Bank of Guizhou in the Nanpanjiang basin of Guizhou and Guangxi, South China" (PDF). Albertiana. 33: 149–168.

- ^ a b Hu, S.-X.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Lü, T.; Xie, T.; Wen, W.; Huang, J.-Y.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "The Luoping biota: exceptional preservation, and new evidence on the Triassic recovery from end-Permian mass extinction". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1716): 2274–2282. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2235. PMC 3119007. PMID 21183583.

External links[]

- Prehistoric archosauromorphs

- Prehistoric reptile genera

- Middle Triassic reptiles of Asia

- Triassic China

- Fossils of China

- Fossil taxa described in 2017