Personal life of Leonardo da Vinci

The Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) left thousands of pages of writings and drawings, but rarely made any references to his personal life.[1] The resulting uncertainty, combined with mythologized anecdotes from his lifetime, has resulted in much speculation and interest in Leonardo's personal life. Particularly, his personal relationships, sexuality, philosophy, religion, vegetarianism, left-handedness and appearance.

Leonardo has long been regarded as the archetypal Renaissance man, described by the Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari as having qualities that "transcended nature" and being "marvellously endowed with beauty, grace and talent in abundance".[2] Interest in and curiosity about Leonardo has continued unabated for five hundred years.[3] Modern descriptions and analysis of Leonardo's character, personal desires and intimate behaviour have been based upon various sources: records concerning him, his biographies, his own written journals, his paintings, his drawings, his associates, and commentaries that were made concerning him by contemporaries.

Biography[]

Leonardo was born to unmarried parents on 15 April 1452, "at the third hour of the night"[4] in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, in the lower valley of the Arno River in the territory of the Republic of Florence. He was the out-of-wedlock son of the wealthy Messer Piero Fruosino di Antonio da Vinci, a Florentine legal notary, and an orphaned girl, Caterina di Meo Lippi.[5][6][7] His full birth name was "Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci", meaning "Leonardo, (son) of (Mes)ser Piero from Vinci". The inclusion of the title "ser" indicated that Leonardo's father was a gentleman.

Leonardo spent his first five years in the hamlet of Anchiano in the home of his mother, then from 1457 lived in the household of his father, grandparents and uncle, Francesco, in the small town of Vinci. His father had married a sixteen-year-old girl named Albiera;[8] Ser Piero married four times and produced children by his two later marriages.[9] Leonardo's seven brothers were later to argue with him over the distribution of his father's estate.

At the age of about fourteen Leonardo was apprenticed by his father to the artist Andrea del Verrocchio. Leonardo was eventually to become a paid employee of Verrocchio's studio. During his time there, Leonardo met many of the most important artists to work in Florence in the late fifteenth century including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Pietro Perugino. Leonardo helped Verrocchio paint The Baptism of Christ, completed around 1475. According to Vasari, Verrocchio, on seeing the beauty of the angel that his young pupil had painted, never painted again.[10]

Florence was at this time a Republic, but the city was increasingly under the influence of a single powerful family, the Medici, led by Lorenzo de' Medici, who came to be known as "Lorenzo the Magnificent". In 1481 Leonardo commenced an important commission, the painting of a large altarpiece for the church of San Donato in Scopeto. The work was never completed. Leonardo left Florence and travelled to Milan carrying a gift from Lorenzo to the regent ruler, Ludovico Sforza. He was employed by Ludovico from 1481 to 1499, during which time his most important works were the Virgin of the Rocks, the Last Supper and a huge model of a horse for an equestrian monument which was never completed. Other important events during this time were the arrival in his studio of the boy Salaì in 1490, and in 1491 the marriage of Ludovico Sforza to Beatrice d'Este, for which he organized the celebrations. When Milan was invaded by the French in 1499, Leonardo left and spent some time in Venice, and possibly Rome and Naples before returning to Florence.[11]

In Florence, Leonardo lived at premises of the Servite Community, and at that time drew the large cartoon for the Madonna and Child and St Anne, which attracted a lot of popular attention. He is also reported to have had a job to do for King Louis XII of France.[11] From 1506 Leonardo was once again based mostly in Milan. In 1507 Francesco Melzi joined his household as an apprentice, and remained with him until his death. In 1513 Leonardo left Milan for Rome and was employed by the Medici family. In 1516 he went to France as court painter to King Francis I.[11] The king gave the chateau of Clos Lucé as his home and regarded him with great esteem. It is said that the king held Leonardo's head as he died. Leonardo is buried in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert adjacent to the Château d'Amboise in France.

Character[]

Leonardo da Vinci was described by his early biographers as a man with great personal appeal, kindness, and generosity. He was generally well loved by his contemporaries. According to Vasari, "Leonardo's disposition was so lovable that he commanded everyone's affection". He was "a sparkling conversationalist" who charmed Ludovico Sforza with his wit. Vasari sums him up by saying:

... his magnificent presence brought comfort to the most troubled soul; he was so persuasive that he could bend other people to his will. ... He was so generous that he fed all his friends, rich or poor... Through his birth Florence received a very great gift, and through his death it sustained an incalculable loss.

Vasari also says:

In the normal course of events many men and women are born with various remarkable qualities and talents; but occasionally, in a way that transcends nature, a single person is marvellously endowed by heaven with beauty, grace and talent in such abundance that he leaves other men far behind... Everyone acknowledged that this was true of Leonardo da Vinci, an artist of outstanding physical beauty who displayed infinite grace in everything he did and who cultivated his genius so brilliantly that all problems he studied were solved with ease.

While painting The Last Supper, Leonardo wrote, "Wine is good, but water is preferable at table. ... Small rooms or dwellings set the mind in the right path, large ones cause it to go astray. ... If you want money in abundance, you will end by not enjoying it." He also wrote, "He who wishes to become rich in a day is hanged in a year."[12]

Some of Leonardo's philosophies can be found in a series of fables he wrote for the court of Ludovico Sforza. These were presented as jests (labelled 'prophecies') in which he told a riddle and made his audience guess the title.[13] Prevalent themes include the dangers of an inflated sense of self-worth, often as described in opposition to the benefits that one can gain through awareness, humility and endeavour. Leonardo also had a distinctive sense of humour, showing newfound friends a lizard he had decorated in scales, a horn and beard made from quicksilver to surprise them,[14] and describing a practical joke in his Treatise on Painting:

If you want to make a fire which will set a hall in a blaze without injury, do this: first perfume the hall with a dense smoke of incense or some other odoriferous substance: it is a good trick to play. ... then go into the room suddenly with a lighted torch and at once it will be in a blaze.[15]

Personal relationships[]

Little is known about Leonardo's intimate relationships from his own writing. Some evidence of Leonardo's personal relationships emerges both from historic records and from the writings of his many biographers.

Pupils[]

Leonardo maintained long-lasting relationships with two pupils who were apprenticed to him as children. These were Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, who entered his household in 1490 at the age of 10,[16][17] and Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Milanese aristocrat who was apprenticed to Leonardo by his father in 1506, at the age of 14, remaining with him until his death.

Gian Giacomo was nicknamed Salaì or il Salaino meaning "the little devil". Vasari describes him as "a graceful and beautiful youth with fine curly hair". The "Little Devil" lived up to his nickname: a year after his entering the household Leonardo made a list of the boy’s misdemeanours, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton". But despite Salaì's thievery and general delinquency—he made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions, spent a fortune on apparel, including twenty-four pairs of shoes, and eventually died in a duel—he remained Leonardo's servant and assistant for thirty years. At Leonardo's death he was bequeathed the Mona Lisa, a valuable piece even then, valued in Salaì's own will at the equivalent of £200,000.

Melzi accompanied Leonardo in his final days in France. On Leonardo's death he wrote a letter to inform Leonardo's brothers, describing him as "like an excellent father to me" and goes on to say: "Everyone is grieved at the loss of such a man that Nature no longer has it in her power to produce."[18] Melzi subsequently played an important role as the guardian of Leonardo's notebooks, preparing them for publication in the form directed by the master. He was not to see this project fully realized, but gathered the Codex Urbinas.

Sexuality[]

Little is self-revealed about Leonardo's sexuality, as, although he left hundreds of pages of writing, very little of it is personal in nature. He left no letters, poetry or diary that indicate any romantic interest. He never married and it cannot be stated with certainty that he had a sexually intimate relationship with any person, male or female. One of the few references that Leonardo made to sexuality in his notebooks states: "The act of procreation and anything that has any relation to it is so disgusting that human beings would soon die out if there were no pretty faces and sensuous dispositions."[19] This statement has been the subject of various extrapolations and interpretations in attempts to gain a picture of his sexuality. He also wrote "Intellectual passion drives out sensuality. ... Whoso curbs not lustful desires puts himself on a level with the beasts."[12]

The only historical document concerning Leonardo's sexual life is an accusation of sodomy made in 1476,[20] while he was still at the workshop of Verrocchio.[21] Florentine court records show that on 9 April 1476, an anonymous denunciation was left in the tamburo (letter box) in the Palazzo della Signoria (town hall) accusing a young goldsmith and male prostitute, Jacopo Saltarelli (sometimes referred to as an artist's model) of being "party to many wretched affairs and consents to please those persons who request such wickedness of him". The denunciation accused four people of sodomizing Saltarelli: Leonardo da Vinci, a tailor named Baccino, Bartolomeo di Pasquino, and Leonardo Tornabuoni, a member of the aristocratic Tornabuoni family. Saltarelli's name was known to the authorities because another man had been convicted of sodomy with him earlier the same year.[22] Charges against the five were dismissed on the condition that no further accusations appear in the tamburo. The same accusation did in fact appear on 7 June, but charges were again dismissed.[23] The charges were dismissed because the accusations did not meet the legal requirement for prosecution: all accusations of sodomy had to be signed, but this one was not. (Such accusations could be made secretly, but not anonymously.) There is speculation that since the family of one of the accused, Leonardo Tornabuoni, was associated with Lorenzo de' Medici, the family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal.[24][25] Sodomy was theoretically an extremely serious offense, carrying the death penalty, but its very seriousness made it equally difficult to prove. It was also an offence for which punishment was very seldom handed down in contemporary Florence, where homosexuality was sufficiently widespread and tolerated to make the word Florenzer (Florentine) slang for homosexual in Germany.[26]

A comedic illustration made in 1495 for a poem by Gaspare Visconti may depict Leonardo as a court lawyer with allusions to his alleged homosexual proclivities.[27] Michael White points out that willingness to discuss aspects of Leonardo's sexual identity has varied according to contemporary attitudes.[28][29] His near-contemporary biographer Vasari makes no reference to Leonardo's sexuality whatsoever.[10] In the 20th century, biographers made explicit references to a probability that Leonardo was homosexual,[30] though others concluded that for much of his life he was celibate.[31]

Elizabeth Abbott, in her History of Celibacy, contends that, although Leonardo was probably homosexual, the trauma of the sodomy case converted him to celibacy for the rest of his life.[32] A similar view of a homosexually inclined but chaste Leonardo appears in a famous 1910 paper by Sigmund Freud, Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood, which analysed a memory Leonardo described of having been attacked as a baby by a bird of prey that opened his mouth and "stuck me with the tail inside my lips again and again". Freud claimed the symbolism was clearly phallic, but argued that Leonardo's homosexuality was latent, and that he did not act on his desires.[33][34] However, Freud's premise was based on an erroneous translation of the bird as a vulture, leading him in the direction of Egyptian mythology, when it was actually a kite in Leonardo's story.[35]

Other authors contend that Leonardo was actively homosexual. Serge Bramly states that "the fact that Leonardo warns against lustfulness certainly need not mean that he himself was chaste".[29] David M. Friedman argues that Leonardo's notebooks show a preoccupation with men and with sexuality uninterrupted by the trial and agrees with art historian Kenneth Clark that Leonardo never became sexless.[33][36]

Michael White, in Leonardo: The First Scientist, says it is likely that the trial simply made Leonardo cautious and defensive about his personal relationships and sexuality, but did not dissuade him from intimate relationships with men: "there is little doubt that Leonardo remained a practising homosexual".[37]

Leonardo's late painting of Saint John the Baptist is often cited as support of the case that Leonardo was homosexual. There is also an erotic drawing of Salaì known as The Incarnate Angel, perhaps by the hand of Leonardo, which was one of a number of such drawings once among those contained in the British Royal Collection, but later dispersed. The particular drawing, showing an angel with an erect phallus, was rediscovered in a German collection in 1991. It appears to be a humorous take on Leonardo's St. John the Baptist.[38] The painting of John the Baptist was copied by several of Leonardo's followers, including Salaì. The drawing may also be by one of Leonardo's pupils, perhaps Salaì himself, as it appears to have been drawn by the right, rather than the left hand, and bears strong resemblance to Salaì's copy of the painting.[citation needed]

Patrons, friends and colleagues[]

Leonardo da Vinci had a number of powerful patrons, including the King of France. He had, over the years, a large number of followers and pupils.

- His patrons included the Medici, Ludovico Sforza and Cesare Borgia, in whose service he spent the years 1502 and 1503, and King Francis I of France.

- He had working relations with two other notable scientists, Luca Pacioli and Marcantonio della Torre, and also collaborated with Niccolò Machiavelli.[39][40]

- He had a close, long-lasting friendship with Isabella d'Este, a renowned patroness of the arts, whose portrait he drew while on a journey that took him through Mantua.

- The de Predis brothers and collaboration on Virgin of the Rocks

- His relationship with Michelangelo (23 years his junior) was always tense and ambivalent, as the two had such contrasting characters.

- He spent a notable amount of time with his pupils Francesco Melzi and Salaì, particularly later in life.

Interests[]

Vasari says of the child Leonardo "He would have been very proficient in his early lessons, if he had not been so volatile and flexible; for he was always setting himself to learn a multitude of things, most of which were shortly abandoned. When he began the study of arithmetic, he made, within a few months, such remarkable progress that he could baffle his master with the questions and problems that he raised... All the time, through all his other enterprises, Leonardo never ceased drawing..."

Leonardo's father, Ser Piero, realising that his son's talents were extraordinary, took some of his drawings to show his friend, Andrea del Verrocchio, who ran one of the largest artists' workshops in Florence. Leonardo was accepted for apprenticeship and "soon proved himself a first class geometrician". Vasari says that during his youth Leonardo made a number of clay heads of smiling women and children from which casts were still being made and sold by the workshop some 80 years later. Among his earliest significant known paintings are the Annunciation in the Uffizi, the angel that he painted as a collaboration with Verrocchio in The Baptism of Christ, and a small predella of the Annunciation to go beneath an altarpiece by Lorenzo di Credi. The little predella picture is probably the earliest.

The diversity of Leonardo's interests, remarked on by Vasari as apparent in his early childhood, was to express itself in his journals which record his scientific observations of nature, his meticulous dissection of corpses to understand anatomy, his experiments with machines for flying, for generating power from water and for besieging cities, his studies of geometry and his architectural plans, as well as personal memos and creative writing including fables.

Philosophy and religion[]

There is not much firsthand information about Leonardo's religious inclination, but most historians have deemed him as Catholic.[41] Leonardo was not a particularly devout man, but referred to God as a kind of supreme being. Leonardo could be described as a spiritual metaphysician,[42] who was interested in Greek philosophy such as that of Plato[43] and Aristotle. He describes friars as the "fathers of the people who know all secrets by inspiration" and calls books such as the Bible "supreme truth",[44] while also jesting that "Many who hold the faith of the Son only build temples in the name of the Mother."[45]

Leonardo argues against the myth of a universal flood (as in the story of Noah), doubting that so much water could have evaporated away from the Earth.[46] In an early example of ichnology, he explains that the fossils of marine shells would have been scattered in such a deluge, and not gathered in groups, which were in fact left at various times on mountains in Lombardy.[47]

Leonardo discredited pagan mythology as well, saying that gods the size of planets would appear as mere specks of light in the universe. He also calls these personifications "mortal ... putrid and corrupt in their sepulchers".[48]

Résumé[]

Leonardo sent the following letter to Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan, in 1482:

Most Illustrious Lord: Having now sufficiently seen and considered the proofs of all those who count themselves masters and inventors in the instruments of war, and finding that their invention and use does not differ in any respect from those in common practice, I am emboldened... to put myself in communication with your Excellency, in order to acquaint you with my secrets. I can construct bridges which are very light and strong and very portable with which to pursue and defeat an enemy... I can also make a kind of cannon, which is light and easy of transport, with which to hurl small stones like hail... I can noiselessly construct to any prescribed point subterranean passages — either straight or winding — passing if necessary under trenches or a river... I can make armored wagons carrying artillery, which can break through the most serried ranks of the enemy. In time of peace, I believe I can give you as complete satisfaction as anyone else in the construction of buildings, both public and private, and in conducting water from one place to another. I can execute sculpture in bronze, marble or clay. Also, in painting, I can do as much as anyone, whoever he may be. If any of the aforesaid things should seem impossible or impractical to anyone, I offer myself as ready to make a trial of them in your park or in whatever place shall please your Excellency, to whom I commend myself with all possible humility.[49]

Musical ability[]

It appears from Vasari's description that Leonardo first learned to play the lyre as a child and that he was very talented at improvisation. In about 1479 he created a lyre in the shape of a horse's head, which was made "mostly of silver", and of "sonorous and resonant" tone. Lorenzo de' Medici saw this lyre and wishing to better his relationship with Ludovico Sforza, the usurping Duke of Milan, he sent Leonardo to present this lyre to the Duke as a gift. Leonardo's musical performances so far surpassed those of Ludovico's court musicians that the Duke was delighted.

Love of nature[]

Leonardo always loved nature. One of the reasons was because of his childhood environment. Near his childhood house were mountains, trees, and rivers. There were also many animals. This environment gave him the perfect chance to study the surrounding area; it also may have encouraged him to have interest in painting. Later in life he recalls his exploration of an ominous cavern in the mountains as formative.[citation needed]

Vegetarianism[]

Leonardo's love of animals has been documented both in contemporary accounts as recorded in early biographies, and in his notebooks. Remarkably for the period, he even questioned the morality of eating animals when it was not necessary for health. Statements from his notebook and a comment by a contemporary have led to the widely held view that he was vegetarian. Additionally, he categorized humans as being in the same set of species as apes and monkeys, just as he did with other animals in their respective genus.[50] He also dissected dead animals for the purpose of comparative anatomy.[51]

Edward MacCurdy (one of the two translators and compilers of Leonardo's notebooks into English) wrote:

...The mere idea of permitting the existence of unnecessary suffering, still more that of taking life, was abhorrent to him. Vasari tells, as an instance of his love of animals, how when in Florence he passed places where birds were sold he would frequently take them from their cages with his own hand, and having paid the sellers the price that was asked would let them fly away in the air, thus giving them back their liberty. That this horror of inflicting pain was such as to lead him to be a vegetarian is to be inferred from a reference which occurs in a letter sent by Andrea Corsali to Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, in which, after telling him of an Indian race called Gujerats, who neither eat anything that contains blood nor permit any injury to any living creature, he adds "like our Leonardo da Vinci".[52][53]

Leonardo wrote the following in his notebooks, which were not deciphered and made available for reading until the 19th century:

If you are as you have described yourself the king of the animals – it would be better for you to call yourself king of the beasts since you are the greatest of them all! – why do you not help them so that they may presently be able to give you their young in order to gratify your palate, for the sake of which you have tried to make yourself a tomb for all the animals? Even more I might say if to speak the entire truth were permitted me.[54]

Weapons and war[]

One might question Leonardo's concern for human life, given his weapon designs. Nothing came of his designs for offensive weapons.[55] It is possible his mention of his capabilities of creating weapons helped him in his quest to find powerful patrons, or perhaps he was fond of drawing them as he was of gargoyles. He did work on fortifications, however. In his own words:

When besieged by ambitious tyrants I find a means of offence and defense in order to preserve the chief gift of nature, which is liberty; and first I would speak of the position of the walls, and then of how the various peoples can maintain their good and just lords.[54]

He referred to war as pazzia bestialissima, the "most bestial madness".[55]

And thou, man, who by these labours dost look upon the marvelous works of nature, if thou judgest it to be an atrocious act to destroy the same, reflect that it is an infinitely atrocious act to take away the life of man.[54]

Physical characteristics[]

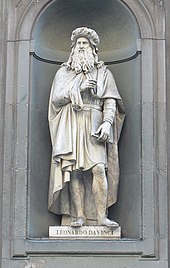

Descriptions and portraits of Leonardo combine to create an image of a man who was tall for his time and place, athletic and extremely handsome. He was 5ft 7 inches, based on the length of his purported skeleton.[56] However, the remains, which were attributed to Leonardo due to the unusually large skull and accompanying stone fragments inscribed "EO [...] DUS VINC", have not yet been positively identified.[57] Portraits indicate that as an older man, he wore his hair long, at a time when most men wore it cropped short, or reaching to the shoulders. While most men were shaven or wore close-cropped beards, Leonardo's beard flowed over his chest.

His clothing is described as being unusual in his choice of bright colours, and at a time when most mature men wore long garments, Leonardo's preferred outfit was the short tunic and hose generally worn by younger men. This image of Leonardo has been recreated in the statue of him that stands outside the Uffizi Gallery.

According to Vasari, Leonardo possessed "great strength and dexterity", being "physically so strong that he could withstand violence and with his right hand he could bend the ring of an iron door knocker or a horseshoe as if they were lead". He was "striking and handsome" and "marvellously endowed by heaven with beauty, grace [and] outstanding physical beauty", and "displayed infinite grace in everything he did".

Author Simon Hewitt claims that a figure in the Sforzida manuscript depicts a youthful Leonardo and that the figure in the illustration has red hair.[58]

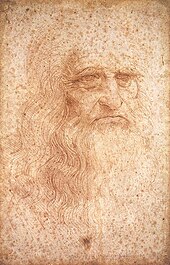

Portraits[]

Leonardo's face is best known from a drawing in red chalk that appears to be a self-portrait. However, there is some controversy over the identity of the subject, because the man represented appears to be of a greater age than the 67 years lived by Leonardo. A solution which has been put forward is that Leonardo deliberately aged himself in the drawing, as a modern forensic artist might do, in order to provide a model for Raphael's painting of him as Plato in The School of Athens. A profile portrait in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan is generally accepted to be a portrait of Leonardo, and also depicts him with flowing beard and long hair. This image was repeated in the woodcut designed for the first edition of Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.[59]

In a 2008 TED talk, artist Siegfried Woldhek, based on Leonardo's features allegedly featured in Andrea del Verrocchio's bronze statue of David, proposed that Leonardo may have done three self-portraits: Portrait of a Musician, the Vitruvian Man, and the aforementioned Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk.[60]

Left-handedness[]

It has been written that Leonardo "may be the most universally recognized left-handed artist of all time", a fact documented by numerous Renaissance authors, and manifested conspicuously in his drawing and handwriting. In his notebooks, he wrote in mirror script because of his left handedness (it was easier for him), and he was falsely accused of trying to protect his work.[61] Leonardo also wrote of using a mirror to judge his compositions more objectively.[62] Early Italian connoisseurs were divided as to whether Leonardo also drew with his right hand. More recently, Anglo-American art historians have for the most part discounted suggestions of ambidexterity.[63]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Zöllner 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists p. 254

- ^ Bortolon, Liana (1967). The Life and Times of Leonardo. London: Paul Hamlyn.

- ^ His birth is recorded in the diary of his paternal grandfather Ser Antonio, as cited by Angela Ottino della Chiesa in Leonardo da Vinci, and Reynal & Co., Leonardo da Vinci (William Morrow and Company, 1956): "A grandson of mine was born April 15, Saturday, three hours into the night". The date was recorded in the Julian calendar; as it was Florentine time and sunset was 6:40 pm, three hours after sunset would be sometime around 9:40 pm which was still April 14 by modern reckoning. The conversion to the New Style calendar adds nine days; hence Leonardo was born April 23 according to the modern calendar.

- ^ "Identity of Leonardo da Vinci's mother revealed in new book". ox.ac. University of Oxford. May 26, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Vezzosi, Alessandro (1997) [1996]. Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Man. ‘New Horizons’ series. Translated by Bonfante-Warren, Alexandra. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30081-7.

- ^ della Chiesa, Angela Ottino (1967). The Complete Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. p. 83.

- ^ Bortolon, Liana (1967). The Life and Times of Leonardo. London: Paul Hamlyn.

- ^ Rosci, p. 20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vasari, Giorgio (2006). The Life of Leonardo da Vinci. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4286-2880-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Martin Kemp, Leonardo seen from the inside out, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-280644-0 pp. 255-274

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wallace 1972, p. 168.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 56.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 150.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 72.

- ^ White, Michael (2000). Leonardo, the first scientist. London: Little, Brown. p. 133. ISBN 0-316-64846-9.

- ^ "Oreno" (in Italian). IT.

- ^ Martin Kemp, Leonardo seen from the inside out, Oxford University Press, (2004) ISBN 0-19-280644-0

- ^ Sigmund Freud: Leonardo da Vinci, translated by Abraham Brill, 1916, chapter I. bartleby.com, after Edmondo Solmi: Leonardo da Vinci. German Translation by Emmi Hirschberg. Berlin, 1908, p. 24 books.google. In Edmondo Solmi: Leonardo (1452-1519), 2nd ed., Firenze G. Barbéra 1907, p. 21 archive.org, the quote reads: « L' atto del coito e le membra a quello adoprate, scriverà Leonardo con ardita espressione, son di tanta bruttura, che, se non fusse la bellezza de' volti e li ornamenti delli opranti e la sfrenata disposizione, la natura perderebbe la spezie umana. » The source is given as W[indsor]. An[atomical manuscript]. A. 8v, p. 227 archive.org, = the vertebral column RL 19007v, cf. Martin Clayton (2010) p. 158 books.google

- ^ "Denuncia contro Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)". Giovannidallorto.com. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Caravaggio and his two cardinals Creighton Gilbert, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio; p. 303 N96.

- ^ Crompton, p. 265

- ^ Wittkower and Wittkower, pp. 170—71

- ^ Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society, 1986, p. 197.

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci — How do we know Leonardo was gay?, website". Bnl.gov. 2001-05-03. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ White, Michael (2000). Leonardo, the first scientist. London: Little, Brown. p. 70. ISBN 0-316-64846-9.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (September 29, 2019). "Italians laughed at Leonardo da Vinci, the ginger genius". The Observer. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ White, Michael (2000). Leonardo, the first scientist. London: Little, Brown. p. 137. ISBN 0-316-64846-9.

(Leonardo's homosexuality has been) "a subject too sensitive to investigate candidly"

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bramly, Serge (1994). Leonardo: The Artist and the Man. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-023175-7.

- ^ White, Michael (2000). Leonardo, the first scientist. London: Little, Brown. p. 7. ISBN 0-316-64846-9.

(Leonardo was) "a homosexual vegetarian born out of wedlock"

- ^ Abbott, Elizabeth (2001). History of Celibacy. James Clark & Co. p. 21. ISBN 0-7188-3006-7.

- ^ Abbott, Elizabeth (2001). History of Celibacy. James Clark & Co. p. 341. ISBN 0-7188-3006-7.

To minimize or deny his homosexual orientation, he probably opted for the safety device of chastity

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friedman, David M (2003). A Mind of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis. Penguin. p. 48. ISBN 0-14-200259-3.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1964). Leonardo Da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood. Norton. ISBN 0-393-00149-0.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 166.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1988). Leonardo da Vinci. Viking. p. 274.

Those who wish, in the interests of morality, to reduce Leonardo, that inexhausible source of creative power, to a neutral or sexless agency, have a strange idea of doing service to his reputation.

- ^ White, Michael (2000). Leonardo, the first scientist. London: Little, Brown. p. 95. ISBN 0-316-64846-9.

- ^ Sewell, Brian. Sunday Telegraph, April 5, 1992.

- ^ Masters, Roger (1996). Machiavelli, Leonardo and the Science of Power.

- ^ Masters, Roger (1998). Fortune is a River: Leonardo Da Vinci and Niccolò Machiavelli's Magnificent Dream to Change the Course of Florentine History. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-452-28090-8.

- ^ Zhu & Zhang 2016, p. 227.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 165.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 103.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 118.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 178.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, pp. 142–148.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 126.

- ^ Full, and somewhat different, translation under the heading Drafts of Letters to Lodovico il Moro (1340-1345). 1340. in The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, volume 2, translated by Jean Paul Richter, 1888, https://archive.org/stream/thenotebooksofle04999gut/8ldv210.txt

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 121.

- ^ Edward MacCurdy, The Mind of Leonardo da Vinci (1928) in Leonardo da Vinci's Ethical Vegetarianism

- ^ Richter, Jean Paul (1970) [1883]. The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci (3rd ed.). Retrieved May 23, 2021.

Alcuni gentili chiamati Guzzarati non si cibano di cosa alcuna che teng consentono che si noccia ad alcuna cosa animata, come il nostro Leonardo da Vinci.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c MacCurdy, Edward (1956) [1939]. "The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Robert Payne, Leonardo (1978)

- ^ Mrs. Charles W. Heaton (1874), Leonardo da Vinci and his works, Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, MT, 2004, p. 204: "The skeleton, which measured five feet eight inches, accords with the height of Leonardo da Vinci. The skull might have served for the model of the portrait Leonardo drew of himself in red chalk a few years before his death. M. Robert Fleury, head master of the Fine Art School at Rome, has handled the skull with respect, and recognized in it the grand and simple outline of this human yet divine head, which once held a world within its limits."

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (May 5, 2016). "Leonardo da Vinci Paintings Analysed for DNA to Solve Grave Mystery". Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (September 29, 2019). "Italians laughed at Leonardo da Vinci, the ginger genius". The Observer. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ Angela Otino della Chiesa, Leonardo da Vinci, Penguin, 1967, ISBN 0-14-008649-8

- ^ TED2008. "Siegfried Woldhek shows how he found the true face of Leonardo". Ted.com. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Bambach, Carmen C., Leonardo, Left-Handed Draftsman and Writer, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived January 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Da Vinci 1971, p. 59.

- ^ Bambach. Archived January 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

Sources[]

- Da Vinci, Leonardo (1971). Taylor, Pamela (ed.). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. New American Library.

- Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books.

- Zhu, Zhenwu; Zhang, Aiping (2016). The Dan Brown Craze: An Analysis of His Formula for Thriller Fiction. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Further reading[]

- Taylor, Rachel Annand (1991). Leonardo The Florentine: A Study in Personality. Easton Press. (hardback).

- Abbott, Elizabeth (2001). A History of Celibacy. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81041-7.

- Crompton, Louis (2006). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02233-5.

- Gilbert, Creighton and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1995). Caravaggio and His Two Cardinals. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01312-5.

- Leonardo da Vinci: anatomical drawings from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1983. ISBN 9780870993626.

- Wittkower, Rudolph and Margaret Wittkower (2006). Born Under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists : A Documented History from Antiquity to the French Revolution. New York, New York Review of Books. ISBN 1-59017-213-2.

External links[]

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Leonardo and the Virgin of the Rocks: What is the real story behind these remarkable paintings?

- Leonardo da Vinci by Maurice Walter Brockwell' at Project Gutenberg

- Vasari Life of Leonardo: in Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

- Leonardo's Will

- Leonardo da Vinci fingerprint reconstructed

- Leonardo da Vinci's Ethical Vegetarianism

- The Art of War: Leonardo da Vinci's War Machines

- Leonardo da Vinci interactive timeline

- Medieval LGBT history

- 16th century in LGBT history

- Renaissance

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Personal life and relationships of individuals