Peytoia

| Peytoia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil specimen, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| |

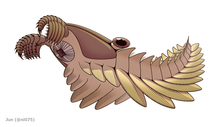

| Reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Dinocaridida |

| Order: | †Radiodonta |

| Family: | †Hurdiidae |

| Genus: | †Peytoia Walcott, 1911 |

| Type species | |

| †Peytoia nathorsti Walcott, 1911

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Peytoia is a genus of hurdiid radiodont that lived in the Cambrian period, containing two species, Peytoia nathorsti and Peytoia infercambriensis.[1] Its two frontal appendages had long bristle-like spines, it had no fan tail, and its short stalked eyes were behind its large head.

Paleontologists have determined that these attributes disqualify Peytoia from apex predator status (as opposed to Anomalocaris), to the extent that it used its appendages to filter water and sediment on the sea floor to find food.[2]

108 specimens of Peytoia are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 0.21% of the community.[3]

Classification[]

Peytoia belongs to the clade Hurdiidae, and is closely related to the contemporary genus Hurdia.[4]

History[]

The history of Peytoia is entangled with that of "Laggania" and Anomalocaris: all three were initially identified as isolated body parts and only later discovered to belong to one type of animal. This was due in part to their makeup of a mixture of mineralized and unmineralized body parts; the oral cone (mouth) and frontal appendage were considerably harder and more easily fossilized than the delicate body.[5]

The first was a detached frontal appendage of Anomalocairs, described by Joseph Frederick Whiteaves in 1892 as a phyllocarid crustacean, because it resembled the abdomen of that taxon.[5] The first fossilized oral cone was discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott, who mistook it for a jellyfish and placed it in the genus Peytoia. In the same paper, Walcott described a poorly-preserved body specimen as Laggania; he interpreted it as a holothurian (sea cucumber). In 1978, Simon Conway Morris noted that the mouthparts of Laggania were identical to Peytoia, but interpreted this as indicating that Laggania was a composite fossil of Peytoia and the sponge Corralio undulata.[6] Later, while clearing what he thought was an unrelated specimen, Harry B. Whittington removed a layer of covering stone to discover the unequivocally connected arm thought to be a phyllocarid abdomen and the oral cone thought to be a jellyfish.[7][5] Whittington linked the two species, but it took several more years for researchers to realize that the continuously juxtaposed Peytoia, Laggania and frontal appendage represented one enormous creature.[5] Laggania and Peytoia were named in the same publication, but Simon Conway Morris selected Peytoia as the valid name in 1978, which makes it the valid name according to International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature rules.[6][8]

A second species, Peytoia infercambriensis, was named in 1975 as Pomerania infercambriensis. Its discoverer, Kazimiera Lendzion, interpreted it as a member of Leanchoiliidae,[9] a family which now known as part of the unrelated megacheirans (great appendage arthropods). It was subsequently renamed Cassubia infercambriensis because the name Pomerania had already been used for an ammonoid.[10] C. infercambriensis was later recognized as a radiodont.[2] It was later determined that the specimen was a composite of a radiodont frontal appendage and the body of an unknown arthropod.[1] Due to the close similarity of the appendage to Peytoia nathorsti, C. infercambriensis was reassigned to Peytoia.

References[]

- ^ a b Daley, A. C.; Legg, D. A. (2015). "A morphological and taxonomic appraisal of the oldest anomalocaridid from the Lower Cambrian of Poland". Geological Magazine. 152 (5): 949–955. doi:10.1017/S0016756815000412.

- ^ a b Dzik, J.; Lendzion, K. (1988). "The Oldest Arthropods of the East European Platform". Lethaia. 21: 29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1988.tb01749.x.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022.

- ^ Vinther, J.; Stein, M.; Longrich, N. R.; Harper, D. A. T. (2014). "A suspension-feeding anomalocarid from the Early Cambrian" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 497–499. doi:10.1038/nature13010. PMID 24670770.

- ^ a b c d Gould, Stephen Jay (1989). Wonderful life: the Burgess Shale and the nature of history. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 194–206. ISBN 0-393-02705-8.

- ^ a b Conway Morris, S. (1978). "Laggania cambria Walcott: A composite fossil". Journal of Paleontology. 52 (1): 126–131.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1998). The crucible of creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–9. ISBN 0-19-850256-7.

- ^ Daley, A. and Bergström, J. (2012). "The oral cone of Anomalocaris is not a classic 'peytoia'." Naturwissenschaften, doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0910-8

- ^ Lendzion, Kazimiera (1975). "Fauna of the Mobergella zone in the Polish Lower Cambrian". 19 (2): 237–242. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Lendzion, Kazimiera (1977). "Cassubia - a new generic name for Pomerania Lendzion, 1975". Geological Quarterly. 21 (1).

External links[]

- "Laggania cambria". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011.

- Burgess Shale fossils

- Cambrian arthropods

- Anomalocaridids