Photovoltaics

Photovoltaics (PV) is the conversion of light into electricity using semiconducting materials that exhibit the photovoltaic effect, a phenomenon studied in physics, photochemistry, and electrochemistry. The photovoltaic effect is commercially utilized for electricity generation and as photosensors.

A photovoltaic system employs solar modules, each comprising a number of solar cells, which generate electrical power. PV installations may be ground-mounted, rooftop-mounted, wall-mounted or floating. The mount may be fixed or use a solar tracker to follow the sun across the sky.

Some hope that photovoltaic technology will produce enough affordable sustainable energy to help mitigate global warming caused by CO

2. Solar PV has specific advantages as an energy source: once installed, its operation generates no pollution and no greenhouse gas emissions, it shows simple scalability in respect of power needs and silicon has large availability in the Earth's crust, although other materials required in PV system manufacture such as silver will eventually constrain further growth in the technology. Other major constraints identified are competition for land use and lack of labor in making funding applications.[1] The use of PV as a main source requires energy storage systems or global distribution by high-voltage direct current power lines causing additional costs, and also has a number of other specific disadvantages such as unstable power generation and the requirement for power companies to compensate for too much solar power in the supply mix by having more reliable conventional power supplies in order to regulate demand peaks and potential undersupply. Production and installation does cause pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and there are no viable systems for recycling the panels once they are at the end of their lifespan after 10 to 30 years.

Photovoltaic systems have long been used in specialized applications as stand-alone installations and grid-connected PV systems have been in use since the 1990s.[2] Photovoltaic modules were first mass-produced in 2000, when German environmentalists and the Eurosolar organization received government funding for a ten thousand roof program.[3]

Decreasing costs has allowed PV to grow as an energy source. This has been partially driven by massive Chinese government investment in developing solar production capacity since 2000, and achieving economies of scale. Much of the price of production is from the key component polysilicon, and most of the world supply is produced in China, especially in Xinjiang. Beside the subsidies, the low prices of solar panels in the 2010s has been achieved through the low price of energy from coal and cheap labour costs in Xinjiang,[4] as well as improvements in manufacturing technology and efficiency.[5][6] Advances in technology and increased manufacturing scale have also increased the efficiency of photovoltaic installations.[2][7] Net metering and financial incentives, such as preferential feed-in tariffs for solar-generated electricity, have supported solar PV installations in many countries.[8] Panel prices dropped by a factor of 4 between 2004 and 2011. Module prices dropped 90% of over the 2010s, but began increasing sharply in 2021.[4][9]

In 2019, worldwide installed PV capacity increased to more than 635 gigawatts (GW) covering approximately two percent of global electricity demand.[10] After hydro and wind powers, PV is the third renewable energy source in terms of global capacity. In 2019 the International Energy Agency expected a growth by 700 - 880 GW from 2019 to 2024.[11] In some instances, PV has offered the cheapest source of electrical power in regions with a high solar potential, with a bid for pricing as low as 0.01567 US$/kWh in Qatar in 2020.[12]

Etymology[]

The term "photovoltaic" comes from the Greek φῶς (phōs) meaning "light", and from "volt", the unit of electromotive force, the volt, which in turn comes from the last name of the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, inventor of the battery (electrochemical cell). The term "photovoltaic" has been in use in English since 1849.[13]

Solar cells[]

Photovoltaics are best known as a method for generating electric power by using solar cells to convert energy from the sun into a flow of electrons by the photovoltaic effect.[14][15]

Solar cells produce direct current electricity from sunlight which can be used to power equipment or to recharge a battery. The first practical application of photovoltaics was to power orbiting satellites and other spacecraft, but today the majority of photovoltaic modules are used for grid-connected systems for power generation. In this case an inverter is required to convert the DC to AC. There is still a smaller market for stand alone systems for remote dwellings, boats, recreational vehicles, electric cars, roadside emergency telephones, remote sensing, and cathodic protection of pipelines.

Photovoltaic power generation employs solar modules composed of a number of solar cells containing a semiconductor material.[16] Copper solar cables connect modules (module cable), arrays (array cable), and sub-fields. Because of the growing demand for renewable energy sources, the manufacturing of solar cells and photovoltaic arrays has advanced considerably in recent years.[17][18][19]

Cells require protection from the environment and are usually packaged tightly in solar modules.

Photovoltaic module power is measured under standard test conditions (STC) in "Wp" (watts peak).[20] The actual power output at a particular place may be less than or greater than this rated value, depending on geographical location, time of day, weather conditions, and other factors.[21] Solar photovoltaic array capacity factors are typically under 25%, which is lower than many other industrial sources of electricity.[22]

Solar cell efficiencies[]

The electrical efficiency of a PV cell is a physical property which represents how much electrical power a cell can produce for a given Solar irradiance. The basic expression for maximum efficiency of a photovoltaic cell is given by the ratio of output power to the incident solar power (radiation flux times area)

The efficiency is measured under ideal laboratory conditions and represents the maximum achievable efficiency of the PV cell or module. Actual efficiency is influenced by temperature, irradiance and spectrum.[citation needed]

Solar cell energy conversion efficiencies for commercially available photovoltaics are around 14–22%.[24][25] Solar cell efficiencies are only 6% for amorphous silicon-based solar cells. In experimental settings, an efficiency of 44.0% has been achieved with experimental multiple-junction concentrated photovoltaics.[26] The US-based speciality gallium arsenide (GaAs) PV manufacturer Alta Devices produces commercial cells with 26% efficiency[27] claiming to have "the world's most efficient solar" single-junction cell dedicated to flexible and lightweight applications. For silicon solar cell, the US company SunPower remains the leader with a certified module efficiency of 22.8%,[28] well above the market average of 15–18%. However, competitor companies are catching up like the South Korean conglomerate LG (21.7% efficiency[29]) or the Norwegian REC Group (21.7% efficiency).[30]

For best performance, terrestrial PV systems aim to maximize the time they face the sun. Solar trackers achieve this by moving PV modules to follow the sun.[citation needed]. Static mounted systems can be optimized by analysis of the sun path. PV modules are often set to latitude tilt, an angle equal to the latitude, but performance can be improved by adjusting the angle for summer or winter. Generally, as with other semiconductor devices, temperatures above room temperature reduce the performance of photovoltaic modules.[31]

Conventionally, direct current (DC) generated electricity from solar PV must be converted to alternating current (AC) used in the power grid, at an average 10% loss during the conversion. An additional efficiency loss occurs in the transition back to DC for battery driven devices and vehicles.[citation needed]

A large amount of energy is also required for the manufacture of the cells.[4]

Effect of the temperature[]

The performance of a photovoltaic module depends on the environmental conditions, mainly on the global incident irradiance G on the module plane. However, the temperature T of the p–n junction also influences the main electrical parameters: the short‐circuit current ISC, the open‐circuit voltage VOC, and the maximum power Pmax. The first studies about the behavior of PV cells under varying conditions of G and T date back several decades ago.1-4 In general, it is known that VOC shows a significant inverse correlation with T, whereas for ISC that correlation is direct, but weaker, so that this increment does not compensate for the decrease of VOC. As a consequence, Pmax reduces when T increases. This correlation between the output power of a solar cell and its junction working temperature depends on the semiconductor material,2 and it is due to the influence of T on the concentration, lifetime, and mobility of the intrinsic carriers, that is, electrons and holes, inside the PV cell.

The temperature sensitivity is usually described by some temperature coefficients, each one expressing the derivative of the parameter it refers to with respect to the junction temperature. The values of these parameters can be found in any PV module data sheet; they are the following:

– β Coefficient of variation of VOC with respect to T, given by ∂VOC/∂T.

– α Coefficient of variation of ISC with respect to T, given by ∂ISC/∂T.

– δ Coefficient of variation of Pmax with respect to T, given by ∂Pmax/∂T.

Techniques for estimating these coefficients from experimental data can be found in the literature.[32] Few studies analyse the variation of the series resistance with respect to the cell or module temperature. This dependency is studied by suitably processing the current–voltage curve. The temperature coefficient of the series resistance is estimated by using the single diode model or the double diode one. [33]

Manufacturing[]

Overall the manufacturing process of creating solar photovoltaics is simple in that it does not require the culmination of many complex or moving parts. Because of the solid state nature of PV systems they often have relatively long lifetimes, anywhere from 10 to 30 years. To increase electrical output of a PV system, the manufacturer must simply add more photovoltaic components and because of this economies of scale are important for manufacturers as costs decrease with increasing output.[34]

While there are many types of PV systems known to be effective, crystalline silicon PV accounted for around 90% of the worldwide production of PV in 2013. Manufacturing silicon PV systems has several steps. First, polysilicon is processed from mined quartz until it is very pure (semi-conductor grade). This is melted down when small amounts of boron, a group III element, are added to make a p-type semiconductor rich in electron holes. Typically using a seed crystal, an ingot of this solution is grown from the liquid polycrystalline. The ingot may also be cast in a mold. Wafers of this semiconductor material are cut from the bulk material with wire saws, and then go through surface etching before being cleaned. Next, the wafers are placed into a phosphorus vapor deposition furnace which lays a very thin layer of phosphorus, a group V element, which creates an n-type semiconducting surface. To reduce energy losses, an anti-reflective coating is added to the surface, along with electrical contacts. After finishing the cell, cells are connected via electrical circuit according to the specific application and prepared for shipping and installation.[35]

Environmental costs of manufacture[]

Solar photovoltaic power is not entirely "clean energy", production produces GHG (Green House Gas) emissions, materials used to build the cells are potentially unsustainable and will run out eventually, the technology uses toxic substances which cause pollution, and there are no viable technologies for recycling solar waste.[36] A large amount of energy is required for the production of the panels, most of which is now produced from coal-fired plants in China.[4] Data required to investigate their impact are sometimes affected by a rather large amount of uncertainty. The values of human labor and water consumption, for example, are not precisely assessed due to the lack of systematic and accurate analyses in the scientific literature.[1] One difficulty in determining impacts due to PV is to determine if the wastes are released to the air, water, or soil during the manufacturing phase.[37] Life-cycle assessments, which look at all different environment impacts ranging from global warming potential, pollution, water depletion and others, are unavailable for PV. Instead, studies have tried to estimate the impact and potential impacts of various types of PV, but these estimates are usually restricted to simply assessing energy costs of the manufacture and/or transport, because these are new technologies and the total environmental impacts of their components and disposal methods are unknown, even for commercially available first generation solar cells, let alone experimental prototypes with no commercial viability.[38]

Thus, estimates of the environmental impacts of PV have focused on carbon dioxide equivalents per kWh or energy pay-back time (EPBT). The EPBT describes the timespan a PV system needs to operate in order to generate the same amount of energy that was used for its manufacture.[39] Another study includes transport energy costs in the EPBT.[40] The EPBT has also been defined completely differently as "the time needed to compensate for the total renewable- and non-renewable primary energy required during the life cycle of a PV system" in another study, which also included installation costs.[41] This energy amortization, given in years, is also referred to as break-even energy payback time.[42] The lower the EPBT, the lower the environmental cost of solar power. The EPBT depends vastly on the location where the PV system is installed (e.g. the amount of sunlight available and the efficiency of the electrical grid)[40] and on the type of system, namely the system's components.[39]

A 2015 review of EPBT estimates of first and second generation PV suggested that there was greater variation in embedded energy than in efficiency of the cells implying that it was mainly the embedded energy that needs to reduced to have a greater reduction in EPBT.[43]

A large amount of energy is required for the production of the panels.[4] In general, the most important component of solar panels, which accounts for much of the energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, is the refining of the polysilicon.[39] China is the source of the majority of the polysilicon in the world, most of it produced in Xinjiang using energy produced from coal-fired plants.[4] As to how much percentage of the EPBT this silicon depends on the type of system. A fully autarkic system requires additional components ('Balance of System', the power inverters, storage, etc..) which significantly increase the energy cost of manufacture, but in a simple rooftop system some 90% of the energy cost is from silicon, with the remainder coming from the inverters and module frame.[39]

In an analysis by Alsema et al. from 1998, the energy payback time was higher than 10 years for the former system in 1997, while for a standard rooftop system the EPBT was calculated as between 3.5 to 8 years.[39][44]

The EPBT relates closely to the concepts of net energy gain (NEG) and energy returned on energy invested (EROI). They are both used in energy economics and refer to the difference between the energy expended to harvest an energy source and the amount of energy gained from that harvest. The NEG and EROI also take the operating lifetime of a PV system into account and a working life of 25 to 30 years is typically assumed. From these metrics, the Energy payback Time can be derived by calculation.[45][46]

EPBT improvements[]

PV systems using crystalline silicon, by far the majority of the systems in practical use, have such a high EPBT because silicon is produced by the reduction of high-grade quartz sand in electric furnaces. This coke-fired smelting process occurs at high temperatures of more than 1000 °C and is very energy intensive, using about 11 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per produced kilogram of silicon.[47] The energy requirements of this process makes the energy cost per unit of silicon produced relatively inelastic, which means that the production process itself will not become more efficient in the future.

Nonetheless, the energy payback time has shortened significantly over the last years, as crystalline silicon cells became ever more efficient in converting sunlight, while the thickness of the wafer material was constantly reduced and therefore required less silicon for its manufacture. Within the last ten years, the amount of silicon used for solar cells declined from 16 to 6 grams per watt-peak. In the same period, the thickness of a c-Si wafer was reduced from 300 μm, or microns, to about 160–190 μm. Crystalline silicon wafers are nowadays only 40 percent as thick as they used to be in 1990, when they were around 400 μm.[citation needed] The sawing techniques that slice crystalline silicon ingots into wafers have also improved by reducing the kerf loss and making it easier to recycle the silicon sawdust.[48][49]

| Parameter | Mono-Si | CdTe |

|---|---|---|

| Cell efficiency | 16.5% | 15.6% |

| Derate cell to module efficiency | 8.5% | 13.9% |

| Module efficiency | 15.1% | 13.4% |

| Wafer thickness / layer thickness | 190 μm | 4.0 μm |

| Kerf loss | 190 μm | – |

| Silver per cell | 9.6 g/m2 | – |

| Glass thickness | 4.0 mm | 3.5 mm |

| Operational lifetime | 30 years | 30 years |

| Source: IEA-PVPS, Life Cycle Assessment, March 2015[50] | ||

Impacts from first-generation PV

Crystalline silicon modules are the most extensively studied PV type in terms of LCA since they are the most commonly used. Mono-crystalline silicon photovoltaic systems (mono-si) have an average efficiency of 14.0%.[51] The cells tend to follow a structure of front electrode, anti-reflection film, n-layer, p-layer, and back electrode, with the sun hitting the front electrode. EPBT ranges from 1.7 to 2.7 years.[52] The cradle to gate of CO2-eq/kWh ranges from 37.3 to 72.2 grams.[53]

Techniques to produce multi-crystalline silicon (multi-si) photovoltaic cells are simpler and cheaper than mono-si, however tend to make less efficient cells, an average of 13.2%.[51] EPBT ranges from 1.5 to 2.6 years.[52] The cradle to gate of CO2-eq/kWh ranges from 28.5 to 69 grams.[53]

Assuming that the following countries had a high quality grid infrastructure as in Europe, in 2020 it was calculated it would take 1.28 years in Ottawa, Canada for a rooftop photovoltaic system to produce the same amount of energy as required to manufacture the silicon in the modules in it (excluding the silver, glass, mounts and other components), 0.97 years in Catania, Italy, and 0.4 years in Jaipur, India. Outside of Europe, where net grid efficiencies are lower, it would take longer. This 'energy payback time' can be seen as the portion of time during the useful lifetime of the module in which the energy production is polluting. At best, this means that a 30-year old panel has produced clean energy for 97% of its lifetime, or that the silicon in the modules in a solar panel produce 97% less greenhouse gas emissions than a coal-fired plant for the same amount of energy (assuming and ignoring many things).[40] Some studies have looked beyond EPBT and GWP to other environmental impacts. In one such study, conventional energy mix in Greece was compared to multi-si PV and found a 95% overall reduction in impacts including carcinogens, eco-toxicity, acidification, eutrophication, and eleven others.[54]

Impacts from second generation

Cadmium telluride (CdTe) is one of the fastest-growing thin film based solar cells which are collectively known as second generation devices. This new thin film device also shares similar performance restrictions (Shockley-Queisser efficiency limit) as conventional Si devices but promises to lower the cost of each device by both reducing material and energy consumption during manufacturing. The global market share of CdTe was 4.7% in 2008.[37] This technology's highest power conversion efficiency is 21%.[55] The cell structure includes glass substrate (around 2 mm), transparent conductor layer, CdS buffer layer (50–150 nm), CdTe absorber and a metal contact layer.

CdTe PV systems require less energy input in their production than other commercial PV systems per unit electricity production. The average CO2-eq/kWh is around 18 grams (cradle to gate). CdTe has the fastest EPBT of all commercial PV technologies, which varies between 0.3 and 1.2 years.[56]

Experimental technologies[]

Crystalline silicon photovoltaics are only one type of PV, and while they represent the majority of solar cells produced currently there are many new and promising technologies that have the potential to be scaled up to meet future energy needs. As of 2018, crystalline silicon cell technology serves as the basis for several PV module types, including monocrystalline, multicrystalline, mono PERC, and bifacial.[57]

Another newer technology, thin-film PV, are manufactured by depositing semiconducting layers of perovskite, a mineral with semiconductor properties, on a substrate in vacuum. The substrate is often glass or stainless-steel, and these semiconducting layers are made of many types of materials including cadmium telluride (CdTe), copper indium diselenide (CIS), copper indium gallium diselenide (CIGS), and amorphous silicon (a-Si). After being deposited onto the substrate the semiconducting layers are separated and connected by electrical circuit by laser scribing.[58][59] Perovskite solar cells are a very efficient solar energy converter and have excellent optoelectronic properties for photovoltaic purposes, but their upscaling from lab-sized cells to large-area modules is still under research.[60] Thin-film photovoltaic materials may possibly become attractive in the future, because of the reduced materials requirements and cost to manufacture modules consisting of thin-films as compared to silicon-based wafers.[61] In 2019 university labs at Oxford, Stanford and elsewhere reported perovskite solar cells with efficiencies of 20-25%.[62]

Other possible future PV technologies include organic, dye-sensitized and quantum-dot photovoltaics.[63] Organic photovoltaics (OPVs) fall into the thin-film category of manufacturing, and typically operate around the 12% efficiency range which is lower than the 12–21% typically seen by silicon based PVs. Because organic photovoltaics require very high purity and are relatively reactive they must be encapsulated which vastly increases cost of manufacturing and meaning that they are not feasible for large scale up. Dye-sensitized PVs are similar in efficiency to OPVs but are significantly easier to manufacture. However these dye-sensitized photovoltaics present storage problems because the liquid electrolyte is toxic and can potentially permeate the plastics used in the cell. Quantum dot solar cells are solution processed, meaning they are potentially scalable, but currently they peak at 12% efficiency.[60]

Copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) is a thin film solar cell based on the copper indium diselenide (CIS) family of chalcopyrite semiconductors. CIS and CIGS are often used interchangeably within the CIS/CIGS community. The cell structure includes soda lime glass as the substrate, Mo layer as the back contact, CIS/CIGS as the absorber layer, cadmium sulfide (CdS) or Zn (S,OH)x as the buffer layer, and ZnO:Al as the front contact.[64] CIGS is approximately 1/100th the thickness of conventional silicon solar cell technologies. Materials necessary for assembly are readily available, and are less costly per watt of solar cell. CIGS based solar devices resist performance degradation over time and are highly stable in the field.

Reported global warming potential impacts of CIGS range from 20.5 – 58.8 grams CO2-eq/kWh of electricity generated for different solar irradiation (1,700 to 2,200 kWh/m2/y) and power conversion efficiency (7.8 – 9.12%).[65] EPBT ranges from 0.2 to 1.4 years,[56] while harmonized value of EPBT was found 1.393 years.[43] Toxicity is an issue within the buffer layer of CIGS modules because it contains cadmium and gallium.[38][66] CIS modules do not contain any heavy metals.

Third-generation PVs are designed to combine the advantages of both the first and second generation devices and they do not have Shockley-Queisser limit, a theoretical limit for first and second generation PV cells. The thickness of a third generation device is less than 1 µm.[67]

One emerging alternative and promising technology is based on an organic-inorganic hybrid solar cell made of methylammonium lead halide perovskites. Perovskite PV cells have progressed rapidly over the past few years and have become one of the most attractive areas for PV research.[68] The cell structure includes a metal back contact (which can be made of Al, Au or Ag), a hole transfer layer (spiro-MeOTAD, P3HT, PTAA, CuSCN, CuI, or NiO), and absorber layer (CH3NH3PbIxBr3-x, CH3NH3PbIxCl3-x or CH3NH3PbI3), an electron transport layer (TiO, ZnO, Al2O3 or SnO2) and a top contact layer (fluorine doped tin oxide or tin doped indium oxide).

There are a limited number of published studies to address the environmental impacts of perovskite solar cells.[68][69][70] The major environmental concern is the lead used in the absorber layer. Due to the instability of perovskite cells lead may eventually be exposed to fresh water during the use phase. These LCA studies looked at human and ecotoxicity of perovskite solar cells and found they were surprisingly low and may not be an environmental issue.[69][70] Global warming potential of perovskite PVs were found to be in the range of 24–1500 grams CO2-eq/kWh electricity production. Similarly, reported EPBT of the published paper range from 0.2 to 15 years. The large range of reported values highlight the uncertainties associated with these studies. Celik et al. (2016) critically discussed the assumptions made in perovskite PV LCA studies.[68]

Two new promising thin film technologies are copper zinc tin sulfide (Cu2ZnSnS4 or CZTS),[38] zinc phosphide (Zn3P2)[38] and single-walled carbon nano-tubes (SWCNT).[71] These thin films are currently only produced in the lab but may be commercialized in the future. The manufacturing of CZTS and (Zn3P2) processes are expected to be similar to those of current thin film technologies of CIGS and CdTe, respectively. While the absorber layer of SWCNT PV is expected to be synthesized with CoMoCAT method.[72] by Contrary to established thin films such as CIGS and CdTe, CZTS, Zn3P2, and SWCNT PVs are made from earth abundant, nontoxic materials and have the potential to produce more electricity annually than the current worldwide consumption.[73][74] While CZTS and Zn3P2 offer good promise for these reasons, the specific environmental implications of their commercial production are not yet known. Global warming potential of CZTS and Zn3P2 were found 38 and 30 grams CO2-eq/kWh while their corresponding EPBT were found 1.85 and 0.78 years, respectively.[38] Overall, CdTe and Zn3P2 have similar environmental impacts but can slightly outperform CIGS and CZTS.[38] A study on environmental impacts of SWCNT PVs by Celik et al., including an existing 1% efficient device and a theoretical 28% efficient device, found that, compared to monocrystalline Si, the environmental impacts from 1% SWCNT was ∼18 times higher due mainly to the short lifetime of three years.[71]

Organic and polymer photovoltaic (OPV) are a relatively new area of research. The tradition OPV cell structure layers consist of a semi-transparent electrode, electron blocking layer, tunnel junction, holes blocking layer, electrode, with the sun hitting the transparent electrode. OPV replaces silver with carbon as an electrode material lowering manufacturing cost and making them more environmentally friendly.[75] OPV are flexible, low weight, and work well with roll-to roll manufacturing for mass production.[76] OPV uses "only abundant elements coupled to an extremely low embodied energy through very low processing temperatures using only ambient processing conditions on simple printing equipment enabling energy pay-back times".[77] Current efficiencies range from 1–6.5%,[41][78] however theoretical analyses show promise beyond 10% efficiency.[77]

Many different configurations of OPV exist using different materials for each layer. OPV technology rivals existing PV technologies in terms of EPBT even if they currently present a shorter operational lifetime. A 2013 study analyzed 12 different configurations all with 2% efficiency, the EPBT ranged from 0.29 to 0.52 years for 1 m2 of PV.[79] The average CO2-eq/kWh for OPV is 54.922 grams.[80]

Where land may be limited, PV can be deployed as floating solar. In 2008 the Far Niente Winery pioneered the world's first "floatovoltaic" system by installing 994 photovoltaic solar panels onto 130 pontoons and floating them on the winery's irrigation pond.[81][82] A benefit of the set up is that the panels are kept at a lower temperature than they would be on land, leading to a higher efficiency of solar energy conversion. The floating panels also reduce the amount of water lost through evaporation and inhibit the growth of algae.[83]

Concentrator photovoltaics is a technology that contrary to conventional flat-plate PV systems uses lenses and curved mirrors to focus sunlight onto small, but highly efficient, multi-junction solar cells. These systems sometimes use solar trackers and a cooling system to increase their efficiency.

Economics[]

Source: Apricus[84] |

There have been major changes in the underlying costs, industry structure and market prices of solar photovoltaics technology, over the years, and gaining a coherent picture of the shifts occurring across the industry value chain globally is a challenge. This is due to: "the rapidity of cost and price changes, the complexity of the PV supply chain, which involves a large number of manufacturing processes, the balance of system (BOS) and installation costs associated with complete PV systems, the choice of different distribution channels, and differences between regional markets within which PV is being deployed". Further complexities result from the many different policy support initiatives that have been put in place to facilitate photovoltaics commercialisation in various countries.[2]

Renewable energy technologies have generally gotten cheaper since their invention.[85][86][87] Renewable energy systems have become cheaper to build than fossil fuel power plants across much of the world, thanks to advances in wind and solar energy technology, in particular.[88]

Hardware costs[]

In 1977 crystalline silicon solar cell prices were at $76.67/W.[89]

Although wholesale module prices remained flat at around $3.50 to $4.00/W in the early 2000s due to high demand in Germany and Spain afforded by generous subsidies and shortage of polysilicon, demand crashed with the abrupt ending of Spanish subsidies after the market crash of 2008, and the price dropped rapidly to $2.00/W. Manufacturers were able to maintain a positive operating margin despite a 50% drop in income due to innovation and reductions in costs. In late 2011, factory-gate prices for crystalline-silicon photovoltaic modules suddenly dropped below the $1.00/W mark, taking many in the industry by surprise, and has caused a number of solar manufacturing companies to go bankrupt throughout the world. The $1.00/W cost is often regarded in the PV industry as marking the achievement of grid parity for PV, but most experts do not believe this price point is sustainable. Technological advancements, manufacturing process improvements, and industry re-structuring, may mean that further price reductions are possible.[2] The average retail price of solar cells as monitored by the Solarbuzz group fell from $3.50/watt to $2.43/watt over the course of 2011.[90] In 2013 wholesale prices had fallen to $0.74/W.[89] This has been cited as evidence supporting 'Swanson's law', an observation similar to the famous Moore's Law, which claims that solar cell prices fall 20% for every doubling of industry capacity.[89] The Fraunhofer Institute defines the 'learning rate' as the drop in prices as the cumulative production doubles, some 25% between 1980 to 2010. Although the prices for modules have dropped quickly, current inverter prices have dropped at a much lower rate, and in 2019 constitute over 61% of the cost per kWp, from a quarter in the early 2000s.[40]

Note that the prices mentioned above are for bare modules, another way of looking at module prices is to include installation costs. In the US, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association, the price of installed rooftop PV modules for homeowners fell from $9.00/W in 2006 to $5.46/W in 2011. Including the prices paid by industrial installations, the national installed price drops to $3.45/W. This is markedly higher than elsewhere in the world, in Germany homeowner rooftop installations averaged at $2.24/W. The cost differences are thought to be primarily based on the higher regulatory burden and lack of a national solar policy in the USA.[91]

By the end of 2012 Chinese manufacturers had production costs of $0.50/W in the cheapest modules.[92] In some markets distributors of these modules can earn a considerable margin, buying at factory-gate price and selling at the highest price the market can support ('value-based pricing').[2]

In California PV reached grid parity in 2011, which is usually defined as PV production costs at or below retail electricity prices (though often still above the power station prices for coal or gas-fired generation without their distribution and other costs).[93] Grid parity had been reached in 19 markets in 2014.[94][95]

Levelised cost of electricity[]

The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) is the cost per kWh based on the costs distributed over the project lifetime, and is thought to be a better metric for calculating viability than price per wattage. LCOEs vary dramatically depending on the location.[2] The LCOE can be considered the minimum price customers will have to pay the utility company in order for it to break even on the investment in a new power station.[5] Grid parity is roughly achieved when the LCOE falls to a similar price as conventional local grid prices, although in actuality the calculations are not directly comparable.[96] Large industrial PV installations had reached grid parity in California in 2011.[87][96] Grid parity for rooftop systems was still believed to be much farther away at this time.[96] Many LCOE calculations are not thought to be accurate, and a large amount of assumptions are required.[2][96] Module prices may drop further, and the LCOE for solar may correspondingly drop in the future.[97]

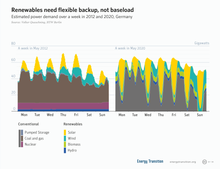

Because energy demands rise and fall over the course of the day, and solar power is limited by the fact that the sun sets, solar power companies must also factor in the additional costs of supplying a more stable alternative energy supplies to the grid in order to stabilize the system, or storing the energy somehow (current battery technology cannot store enough power). These costs are not factored into LCOE calculations, nor are special subsidies or premiums that may make buying solar power more attractive.[5] The unreliability and temporal variation in generation of solar and wind power is a major problem. Too much of these volatile power sources can cause instability of the entire grid.[98]

As of 2017 power-purchase agreement prices for solar farms below $0.05/kWh are common in the United States, and the lowest bids in some Persian Gulf countries were about $0.03/kWh.[99] The goal of the United States Department of Energy is to achieve a levelised cost of energy for solar PV of $0.03/kWh for utility companies.[100]

Subsidies and financing[]

Financial incentives for photovoltaics, such as feed-in tariffs (FITs), are often been offered to electricity consumers to install and operate solar-electric generating systems, and in some countries such subsidies are the only way photovoltaics can remain economically profitable. In Germany FIT subsidies are generally around €0.13 above the normal retail price of a kWh (€0.05).[101] PV FITs have been crucial for the adoption of the industry, and are available to consumers in over 50 countries as of 2011. Germany and Spain have been the most important countries regarding offering subsidies for PV, and the policies of these countries have driven demand in the past.[2] Some US solar cell manufacturing companies have repeatedly complained that the dropping prices of PV module costs have been achieved due to subsidies by the government of China, and the dumping of these products below fair market prices. US manufacturers generally recommend high tariffs on foreign supplies to allow them remain profitable. In response to these concerns, the Obama administration began to levy tariffs on US consumers of these products in 2012 to raise prices for domestic manufacturers.[2] Under the Trump administration the US government imposed further tariffs on US consumers to restrict trade in solar modules.[citation needed] The USA, however, also subsidies the industry, offering consumers a 30% federal tax credit to purchase modules. In Hawaii federal and state subsidies chop off up to two thirds of the installation costs.[91]

Some environmentalists have promoted the idea that government incentives should be used in order to expand the PV manufacturing industry to reduce costs of PV-generated electricity much more rapidly to a level where it is able to compete with fossil fuels in a free market. This is based on the theory that when the manufacturing capacity doubles, economies of scale will cause the prices of the solar products to halve.[5]

In many countries there is access to capital is lacking to develop PV projects. To solve this problem, securitization has been proposed to accelerate development of solar photovoltaic projects.[93][102] For example, SolarCity offered the first U.S. asset-backed security in the solar industry in 2013.[103]

Other[]

Photovoltaic power is also generated during a time of day that is close to peak demand (precedes it) in electricity systems with high use of air conditioning. Since large-scale PV operation requires back-up in the form of spinning reserves, its marginal cost of generation in the middle of the day is typically lowest, but not zero, when PV is generating electricity. This can be seen in Figure 1 of this paper:.[104] For residential properties with private PV facilities networked to the grid, the owner may be able earn extra money when the time of generation is included, as electricity is worth more during the day than at night.[105]

One journalist theorised in 2012 that if the energy bills of Americans were forced upwards by imposing an extra tax of $50/ton on carbon dioxide emissions from coal-fired power, this could have allowed solar PV to appear more cost-competitive to consumers in most locations.[90]

Growth[]

Solar photovoltaics formed the largest body of research among the seven sustainable energy types examined in a global bibliometric study, with the annual scientific output growing from 9,094 publications in 2011 to 14,447 publications in 2019.[106]

Likewise, the application of solar photovoltaics is growing rapidly and worldwide installed capacity reached about 515 gigawatts (GW) by 2018.[107] The total power output of the world's PV capacity in a calendar year is now beyond 500 TWh of electricity. This represents 2% of worldwide electricity demand. More than 100 countries use solar PV.[108][109] China is followed by the United States and Japan, while installations in Germany, once the world's largest producer, have been slowing down.

Honduras generated the highest percentage of its energy from solar in 2019, 14.8%.[110] As of 2019, Vietnam has the highest installed capacity in Southeast Asia, about 4.5 GW.[111] The annualized installation rate of about 90 W per capita per annum places Vietnam among world leaders.[111] Generous Feed-in tariff (FIT) and government supporting policies such as tax exemptions were the key to enable Vietnam's solar PV boom. Underlying drivers include the government's desire to enhance energy self-sufficiency and the public's demand for local environmental quality.[111]

A key barrier is limited transmission grid capacity.[111]

China has the world's largest solar power capacity, with 253 GW of installed capacity at the end-2020 compared with about 151 GW in the European Union, according to International Energy Agency data. (https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/china-add-55-65-gw-solar-power-capacity-2021-industry-body-2021-07-22/)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Data: IEA-PVPS Snapshot of Global PV Markets 2020 report, April 2020[112] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2017 it was thought probable that by 2030 global PV installed capacities could be between 3,000 and 10,000 GW.[99] Greenpeace in 2010 claimed that 1,845 GW of PV systems worldwide could be generating approximately 2,646 TWh/year of electricity by the year 2030, and by 2050 over 20% of all electricity could be provided by PV.[113]

Applications[]

Photovoltaic systems[]

A photovoltaic system, or solar PV system is a power system designed to supply usable solar power by means of photovoltaics. It consists of an arrangement of several components, including solar panels to absorb and directly convert sunlight into electricity, a solar inverter to change the electric current from DC to AC, as well as mounting, cabling and other electrical accessories. PV systems range from small, roof-top mounted or building-integrated systems with capacities from a few to several tens of kilowatts, to large utility-scale power stations of hundreds of megawatts. Nowadays, most PV systems are grid-connected, while stand-alone systems only account for a small portion of the market.

- Rooftop and building integrated systems

- Photovoltaic arrays are often associated with buildings: either integrated into them, mounted on them or mounted nearby on the ground. Rooftop PV systems are most often retrofitted into existing buildings, usually mounted on top of the existing roof structure or on the existing walls. Alternatively, an array can be located separately from the building but connected by cable to supply power for the building. Building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) are increasingly incorporated into the roof or walls of new domestic and industrial buildings as a principal or ancillary source of electrical power.[114] Roof tiles with integrated PV cells are sometimes used as well. Provided there is an open gap in which air can circulate, rooftop mounted solar panels can provide a passive cooling effect on buildings during the day and also keep accumulated heat in at night.[115] Typically, residential rooftop systems have small capacities of around 5–10 kW, while commercial rooftop systems often amount to several hundreds of kilowatts. Although rooftop systems are much smaller than ground-mounted utility-scale power plants, they account for most of the worldwide installed capacity.[116]

- Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector

- Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector (PVT) are systems that convert solar radiation into thermal and electrical energy. These systems combine a solar PV cell, which converts sunlight into electricity, with a solar thermal collector, which captures the remaining energy and removes waste heat from the PV module. The capture of both electricity and heat allow these devices to have higher exergy and thus be more overall energy efficient than solar PV or solar thermal alone.[117][118]

- Power stations

- Many utility-scale solar farms have been constructed all over the world. In 2011 the 579-megawatt (MWAC) Solar Star project was proposed, to be followed by the Desert Sunlight Solar Farm and the Topaz Solar Farm in the future, both with a capacity of 550 MWAC, to be constructed by US-company First Solar, using CdTe modules, a thin-film PV technology. All three power stations will be located in the Californian desert.[119] When the Solar Star project was completed in 2015, it was the world's largest photovoltaic power station at the time.[120]

- Agrivoltaics

- A number of experimental solar farms have been established around the world that attempt to integrate solar power generation with agriculture. An Italian manufacturer has promoted a design which track the sun's daily path across the sky to generate more electricity than conventional fixed-mounted systems.[121]

- Rural electrification

- Developing countries where many villages are often more than five kilometres away from grid power are increasingly using photovoltaics. In remote locations in India a rural lighting program has been providing solar powered LED lighting to replace kerosene lamps. The solar powered lamps were sold at about the cost of a few months' supply of kerosene.[122][123] Cuba is working to provide solar power for areas that are off grid.[124] More complex applications of off-grid solar energy use include 3D printers.[125] RepRap 3D printers have been solar powered with photovoltaic technology,[126] which enables distributed manufacturing for sustainable development. These are areas where the social costs and benefits offer an excellent case for going solar, though the lack of profitability has relegated such endeavors to humanitarian efforts. However, in 1995 solar rural electrification projects had been found to be difficult to sustain due to unfavorable economics, lack of technical support, and a legacy of ulterior motives of north-to-south technology transfer.[127]

- Standalone systems

- Until a decade or so ago, PV was used frequently to power calculators and novelty devices. Improvements in integrated circuits and low power liquid crystal displays make it possible to power such devices for several years between battery changes, making PV use less common. In contrast, solar powered remote fixed devices have seen increasing use recently in locations where significant connection cost makes grid power prohibitively expensive. Such applications include solar lamps, water pumps,[128] parking meters,[129][130] emergency telephones, trash compactors,[131] temporary traffic signs, charging stations,[132][133] and remote guard posts and signals.

- In transport

- PV has traditionally been used for electric power in space. PV is rarely used to provide motive power in transport applications, but it can provide auxiliary power in boats and cars. Some automobiles are fitted with solar-powered air conditioning.[134] A self-contained solar vehicle would have limited power and utility, but a solar-charged electric vehicle allows use of solar power for transportation. Solar-powered cars, boats[135] and airplanes[136] have been demonstrated, with the most practical and likely of these being solar cars.[137] The Swiss solar aircraft, Solar Impulse 2, achieved the longest non-stop solo flight in history and completed the first solar-powered aerial circumnavigation of the globe in 2016.

- Telecommunication and signaling

- Solar PV power is ideally suited for telecommunication applications such as local telephone exchange, radio and TV broadcasting, microwave and other forms of electronic communication links. This is because, in most telecommunication application, storage batteries are already in use and the electrical system is basically DC. In hilly and mountainous terrain, radio and TV signals may not reach as they get blocked or reflected back due to undulating terrain. At these locations, low power transmitters (LPT) are installed to receive and retransmit the signal for local population.[138]

- Spacecraft applications

- Solar panels on spacecraft are usually the sole source of power to run the sensors, active heating and cooling, and communications. A battery stores this energy for use when the solar panels are in shadow. In some, the power is also used for spacecraft propulsion—electric propulsion.[139] Spacecraft were one of the earliest applications of photovoltaics, starting with the silicon solar cells used on the Vanguard 1 satellite, launched by the US in 1958.[140] Since then, solar power has been used on missions ranging from the MESSENGER probe to Mercury, to as far out in the solar system as the Juno probe to Jupiter. The largest solar power system flown in space is the electrical system of the International Space Station. To increase the power generated per kilogram, typical spacecraft solar panels use high-cost, high-efficiency, and close-packed rectangular multi-junction solar cells made of gallium arsenide (GaAs) and other semiconductor materials.[139]

- Specialty Power Systems

- Photovoltaics may also be incorporated as energy conversion devices for objects at elevated temperatures and with preferable radiative emissivities such as heterogeneous combustors.[141]

- Indoor Photovoltaics (IPV)

- Indoor photovoltaics have the potential to supply power to the Internet of Things, such as smart sensors and communication devices, providing a solution to the battery limitations such as power consumption, toxicity, and maintenance. Ambient indoor lighting, such as LEDs and fluorescent lights, emit enough radiation to power small electronic devices or devices with low-power demand.[142] In these applications, indoor photovoltaics will be able to improve reliability and increase lifetimes of wireless networks, especially important with the significant number of wireless sensors that will be installed in the coming years.[143]

- Due to the lack of access to solar radiation, the intensity of energy harvested by indoor photovoltaics is usually three orders of magnitude smaller than sunlight, which will affect the efficiencies of the photovoltaic cells. The optimal band gap for indoor light harvesting is around 1.9-2 eV, compared to the optimum of 1.4 eV for outdoor light harvesting. The increase in optimal band gap also results in a larger open-circuit voltage (VOC), which affects the efficiency as well.[142] Silicon photovoltaics, the most common type of photovoltaic cell in the market, is only able to reach an efficiency of around 8% when harvesting ambient indoor light, compared to its 26% efficiency in sunlight. One possible alternative is to use amorphous silicon, a-Si, as it has a wider band gap of 1.6 eV compared to its crystalline counterpart, causing it to be more suitable to capture the indoor light spectra.[143]

- Other promising materials and technologies for indoor photovoltaics include thin-film materials, III-V light harvesters, organic photovoltaics (OPV), and perovskite solar cells.

- There has been various organic photovoltaics that have demonstrated efficiencies of over 16% from indoor lighting, despite having low efficiencies in energy harvesting under sunlight.[143] This is due to the fact that OPVs have a large absorption coefficient, adjustable absorptions ranges, as well as small leakage currents in dim light, allowing them to convert indoor lighting more efficiently compared to inorganic PVs.[142]

- Perovskite solar cells have been tested to display efficiencies over 25% in low light levels.[143] While perovskite solar cells often contain lead, raising the concern of toxicity, lead-free perovskite inspired materials also show promise as indoor photovoltaics.[147] While plenty of research is being conducted on perovskite cells, further research is needed to explore its possibilities for IPVs and developing products that can be used to power the internet of things.

Photo sensors[]

Photosensors are sensors of light or other electromagnetic radiation.[148] A photo detector has a p–n junction that converts light photons into current. The absorbed photons make electron–hole pairs in the depletion region. Photodiodes and photo transistors are a few examples of photo detectors. Solar cells convert some of the light energy absorbed into electrical energy.

Experimental technology[]

A number of solar modules may also be mounted vertically above each other in a tower, if the zenith distance of the Sun is greater than zero, and the tower can be turned horizontally as a whole and each module additionally around a horizontal axis. In such a tower the modules can follow the Sun exactly. Such a device may be described as a ladder mounted on a turnable disk. Each step of that ladder is the middle axis of a rectangular solar panel. In case the zenith distance of the Sun reaches zero, the "ladder" may be rotated to the north or the south to avoid a solar module producing a shadow on a lower one. Instead of an exactly vertical tower one can choose a tower with an axis directed to the polar star, meaning that it is parallel to the rotation axis of the Earth. In this case the angle between the axis and the Sun is always larger than 66 degrees. During a day it is only necessary to turn the panels around this axis to follow the Sun. Installations may be ground-mounted (and sometimes integrated with farming and grazing)[149] or built into the roof or walls of a building (building-integrated photovoltaics).

Efficiency[]

The most efficient type of solar cell to date is a multi-junction concentrator solar cell with an efficiency of 46.0% produced by Fraunhofer ISE in December 2014.[150] The highest efficiencies achieved without concentration include a material by Sharp Corporation at 35.8% using a proprietary triple-junction manufacturing technology in 2009,[151] and Boeing Spectrolab (40.7% also using a triple-layer design).

There is an ongoing effort to increase the conversion efficiency of PV cells and modules, primarily for competitive advantage. In order to increase the efficiency of solar cells, it is important to choose a semiconductor material with an appropriate band gap that matches the solar spectrum. This will enhance the electrical and optical properties. Improving the method of charge collection is also useful for increasing the efficiency. There are several groups of materials that are being developed. Ultrahigh-efficiency devices (η>30%)[152] are made by using GaAs and GaInP2 semiconductors with multijunction tandem cells. High-quality, single-crystal silicon materials are used to achieve high-efficiency, low cost cells (η>20%).

Recent developments in organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs) have made significant advancements in power conversion efficiency from 3% to over 15% since their introduction in the 1980s.[153] To date, the highest reported power conversion efficiency ranges from 6.7% to 8.94% for small molecule, 8.4%–10.6% for polymer OPVs, and 7% to 21% for perovskite OPVs.[154][155] OPVs are expected to play a major role in the PV market. Recent improvements have increased the efficiency and lowered cost, while remaining environmentally-benign and renewable.

Several companies have begun embedding power optimizers into PV modules called smart modules. These modules perform maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for each module individually, measure performance data for monitoring, and provide additional safety features. Such modules can also compensate for shading effects, wherein a shadow falling across a section of a module causes the electrical output of one or more strings of cells in the module to decrease.[156]

One of the major causes for the decreased performance of cells is overheating. The efficiency of a solar cell declines by about 0.5% for every 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature. This means that a 100 degree increase in surface temperature could decrease the efficiency of a solar cell by about half. Self-cooling solar cells are one solution to this problem. Rather than using energy to cool the surface, pyramid and cone shapes can be formed from silica, and attached to the surface of a solar panel. Doing so allows visible light to reach the solar cells, but reflects infrared rays (which carry heat).[157]

Advantages[]

The 122 PW of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface is plentiful—almost 10,000 times more than the 13 TW equivalent of average power consumed in 2005 by humans.[158] This abundance leads to the suggestion that it will not be long before solar energy will become the world's primary energy source.[159] Additionally, solar electric generation has the highest power density (global mean of 170 W/m2) among renewable energies.[158]

Solar power is pollution-free during use, which enables it to cut down on pollution when it is substituted for other energy sources. For example, MIT estimated that 52,000 people per year die prematurely in the U.S. from coal-fired power plant pollution[160] and all but one of these deaths could be prevented from using PV to replace coal.[161][162] Production end-wastes and emissions are manageable using existing pollution controls. End-of-use recycling technologies are under development[163] and policies are being produced that encourage recycling from producers.[164]

PV installations could ideally operate for 100 years or even more[165] with little maintenance or intervention after their initial set-up, so after the initial capital cost of building any solar power plant, operating costs are extremely low compared to existing power technologies.

Grid-connected solar electricity can be used locally thus reducing transmission/distribution losses (transmission losses in the US were approximately 7.2% in 1995).[166]

Compared to fossil and nuclear energy sources, very little research money has been invested in the development of solar cells, so there is considerable room for improvement. Nevertheless, experimental high efficiency solar cells already have efficiencies of over 40% in case of concentrating photovoltaic cells[167] and efficiencies are rapidly rising while mass-production costs are rapidly falling.[168]

In some states of the United States, much of the investment in a home-mounted system may be lost if the homeowner moves and the buyer puts less value on the system than the seller. The city of Berkeley developed an innovative financing method to remove this limitation, by adding a tax assessment that is transferred with the home to pay for the solar panels.[169] Now known as PACE, Property Assessed Clean Energy, 30 U.S. states have duplicated this solution.[170]

There is evidence, at least in California, that the presence of a home-mounted solar system can actually increase the value of a home. According to a paper published in April 2011 by the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory titled An Analysis of the Effects of Residential Photovoltaic Energy Systems on Home Sales Prices in California:

The research finds strong evidence that homes with PV systems in California have sold for a premium over comparable homes without PV systems. More specifically, estimates for average PV premiums range from approximately $3.9 to $6.4 per installed watt (DC) among a large number of different model specifications, with most models coalescing near $5.5/watt. That value corresponds to a premium of approximately $17,000 for a relatively new 3,100 watt PV system (the average size of PV systems in the study).[171]

Disadvantages[]

- Pollution and Energy in Production

PV has been a well-known method of generating clean, emission-free electricity. PV systems are often made of PV modules and inverter (changing DC to AC). PV modules are mainly made of PV cells, which has no fundamental difference from the material used for making computer chips. The process of producing PV cells is energy-intensive and involves highly poisonous and environmentally toxic chemicals. There are a few PV manufacturing plants around the world producing PV modules with energy produced from PV. This counteractive measure considerably reduces the carbon footprint of the manufacturing process of PV cells. Management of the chemicals used and produced during the manufacturing process is subject to the factories' local laws and regulations.[citation needed]

- Impact on Electricity Network

For behind-the-meter rooftop photovoltaic systems, the energy flow becomes two-way. When there is more local generation than consumption, electricity is exported to the grid, allowing for net metering. However, electricity networks traditionally are not designed to deal with two-way energy transfer, which may introduce technical issues. An over-voltage issue may come out as the electricity flows from these PV households back to the network.[172] There are solutions to manage the over-voltage issue, such as regulating PV inverter power factor, new voltage and energy control equipment at electricity distributor level, re-conductor the electricity wires, demand side management, etc. There are often limitations and costs related to these solutions.

High generation during the middle of the day reduces the net generation demand, but higher peak net demand as the sun goes down can require rapid ramping of utility generating stations, producing a load profile called the duck curve.

- Implications for Electricity Bill Management and Energy Investment

There is no silver bullet in electricity or energy demand and bill management, because customers (sites) have different specific situations, e.g. different comfort/convenience needs, different electricity tariffs, or different usage patterns. Electricity tariff may have a few elements, such as daily access and metering charge, energy charge (based on kWh, MWh) or peak demand charge (e.g. a price for the highest 30min energy consumption in a month). PV is a promising option for reducing energy charges when electricity prices are reasonably high and continuously increasing, such as in Australia and Germany. However, for sites with peak demand charge in place, PV may be less attractive if peak demands mostly occur in the late afternoon to early evening, for example in residential communities. Overall, energy investment is largely an economic decision and it is better to make investment decisions based on systematic evaluation of options in operational improvement, energy efficiency, onsite generation and energy storage.[173][174]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Photovoltaics. |

- Agrivoltaic

- American Solar Energy Society

- Anomalous photovoltaic effect

- Copper in renewable energy § Solar photovoltaic power generation

- Cost of electricity by source

- Energy demand management

- Electromotive force § Solar cell

- Graphene § Solar cells

- List of photovoltaics companies

- List of solar cell manufacturers

- Photoelectrochemical cell

- Quantum efficiency § Quantum efficiency of solar cells

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Solar cell fabric

- Solar module quality assurance

- Solar photovoltaic monitoring

- Solar power by country

- Solar thermal energy

- Theory of solar cell

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lo Piano, Samuele; Mayumi, Kozo (2017). "Toward an integrated assessment of the performance of photovoltaic systems for electricity generation". Applied Energy. 186 (2): 167–74. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.05.102.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Bazilian, M.; Onyeji, I.; Liebreich, M.; MacGill, I.; Chase, J.; Shah, J.; Gielen, D.; Arent, D.; Landfear, D.; Zhengrong, S. (2013). "Re-considering the economics of photovoltaic power" (PDF). Renewable Energy. 53: 329–338. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.1880. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.11.029. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Palz, Wolfgang (2013). Solar Power for the World: What You Wanted to Know about Photovoltaics. CRC Press. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-981-4411-87-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Biden's New Problem: Rising Solar Panel Prices". Institute for Energy Research. 2 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Why did renewables become so cheap so fast?". Our World in Data. 1 December 2020.

- ^ Shubbak, Mahmood H. (2019). "The technological system of production and innovation: The case of photovoltaic technology in China". Research Policy. 48 (4): 993–1015. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.003.

- ^ Swanson, R. M. (2009). "Photovoltaics Power Up" (PDF). Science. 324 (5929): 891–2. doi:10.1126/science.1169616. PMID 19443773. S2CID 37524007.

- ^ Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st century (REN21), Renewables 2010 Global Status Report, Paris, 2010, pp. 1–80.

- ^ Xiao, Carrie (7 June 2021). "Tackling solar's polysilicon crisis, part one: Supply chain flexibility, differentiation and rigorous testing". PV Tech Premium. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "PHOTOVOLTAICS REPORT" (PDF). Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems. 16 September 2020. p. 4.

- ^ "Renewables 2019". IEA. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "KAHRAMAA and Siraj Energy Sign Agreements for Al-Kharsaah Solar PV Power Plant". Qatar General Electricity & Water Corporation “KAHRAMAA”. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Smee, Alfred (1849). Elements of electro-biology,: or the voltaic mechanism of man; of electro-pathology, especially of the nervous system; and of electro-therapeutics. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 15.

- ^ Photovoltaic Effect Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mrsolar.com. Retrieved 12 December 2010

- ^ The photovoltaic effect Archived 12 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclobeamia.solarbotics.net. Retrieved on 12 December 2010.

- ^ Jacobson, Mark Z. (2009). "Review of Solutions to Global Warming, Air Pollution, and Energy Security". Energy & Environmental Science. 2 (2): 148–173. Bibcode:2009GeCAS..73R.581J. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.180.4676. doi:10.1039/B809990C.

- ^ German PV market. Solarbuzz.com. Retrieved on 3 June 2012.

- ^ BP Solar to Expand Its Solar Cell Plants in Spain and India Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Renewableenergyaccess.com. 23 March 2007. Retrieved on 3 June 2012.

- ^ Bullis, Kevin (23 June 2006). Large-Scale, Cheap Solar Electricity. Technologyreview.com. Retrieved on 3 June 2012.

- ^ Luque, Antonio & Hegedus, Steven (2003). Handbook of Photovoltaic Science and Engineering. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-49196-5.

- ^ The PVWatts Solar Calculator Retrieved on 7 September 2012

- ^ Massachusetts: a Good Solar Market Archived 12 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Remenergyco.com. Retrieved on 31 May 2013.

- ^ Measuring PV Efficiency. pvpower.com

- ^ Schultz, O.; Mette, A.; Preu, R.; Glunz, S.W. "Silicon Solar Cells with Screen-Printed Front Side Metallization Exceeding 19% Efficiency". The compiled state-of-the-art of PV solar technology and deployment. 22nd European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, EU PVSEC 2007. Proceedings of the international conference. CD-ROM : Held in Milan, Italy, 3 – 7 September 2007. pp. 980–983. ISBN 978-3-936338-22-5.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary. (20 June 2011) Sunpower Panels Awarded Guinness World Record. Reuters.com. Retrieved on 31 May 2013.

- ^ "UD-led team sets solar cell record, joins DuPont on $100 million project". UDaily. University of Delaware. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Alta Devices product solar cell" (PDF).

- ^ "SunPower is manufacturing solar panels verified at 22.8 percent efficiency". 8 October 2015.

- ^ "LG375A1C-V5 NeON ® R ACe Solar Panel with Built-in Microinverter System | LG US Solar". LG USA.

- ^ "REC 380AA 21.7% module efficiency" (PDF).

- ^ Vick, B.D., Clark, R.N. (2005). Effect of module temperature on a Solar-PV AC water pumping system, pp. 159–164 in: Proceedings of the International Solar Energy Society (ISES) 2005 Solar Water Congress: Bringing water to the World, 8–12 August 2005, Orlando, Florida.

- ^ Piliougine, M.; Oukaja, A.; Sidrach‐de‐Cardona, M.; Spagnuolo, G. (2021). "Temperature coefficients of degraded crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules at outdoor onditions". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 29 (5): 558–570. doi:10.1002/pip.3396.

- ^ Piliougine, M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Sidrach‐de‐Cardona, M. (2020). "Series resistance temperature sensitivity in degraded mono–crystalline silicon modules". Renewable Energy. 162: 677–684. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.08.026.

- ^ Platzer, Michael (27 January 2015). "U.S. Solar Photovoltaic Manufacturing: Industry Trends, Global Competition, Federal Support". Congressional Research Service.

- ^ "How PV Cells Are Made". www.fsec.ucf.edu. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Are we headed for a solar waste crisis?". Environmentalprogress.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fthenakis, V. M., Kim, H. C. & Alsema, E. (2008). "Emissions from photovoltaic life cycles". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (6): 2168–2174. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.2168F. doi:10.1021/es071763q. hdl:1874/32964. PMID 18409654.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Collier, J., Wu, S. & Apul, D. (2014). "Life cycle environmental impacts from CZTS (copper zinc tin sulfide) and Zn3P2 (zinc phosphide) thin film PV (photovoltaic) cells". Energy. 74: 314–321. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2014.06.076.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "An analysis of the energy efficiency of photovoltaic cells in reducing CO2 emmisions" (PDF). clca.columbia.edu. 31 May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "PHOTOVOLTAICS REPORT" (PDF). Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems. 16 September 2020. p. 36, 43, 46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anctil, A., Babbitt, C. W., Raffaelle, R. P. & Landi, B. J. (2013). "Cumulative energy demand for small molecule and polymer photovoltaics". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 21 (7): 1541–1554. doi:10.1002/pip.2226.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Ibon Galarraga, M. González-Eguino, Anil Markandya (1 January 2011). Handbook of Sustainable Energy. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0857936387. Retrieved 9 May 2017 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bhandari, K. P., Collier, J. M., Ellingson, R. J. & Apul, D. S. (2015). "Energy payback time (EPBT) and energy return on energy invested (EROI) of solar photovoltaic systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 47: 133–141. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.057.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "An analysis of the energy efficiency of photovoltaic cells in reducing CO2 emmisions". University of Portsmouth. 31 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015.

Energy Pay Back time comparison for Photovoltaic Cells (Alsema, Frankl, Kato, 1998, p. 5

- ^ Marco Raugei, Pere Fullana-i-Palmer and Vasilis Fthenakis (March 2012). "The Energy Return on Energy Investment (EROI) of Photovoltaics: Methodology and Comparisons with Fossil Fuel Life Cycles" (PDF). www.bnl.gov/. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Vasilis Fthenakis, Rolf Frischknecht, Marco Raugei, Hyung Chul Kim, Erik Alsema, Michael Held and Mariska de Wild-Scholten (November 2011). "Methodology Guidelines on Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity" (PDF). www.iea-pvps.org/. IEA-PVPS. pp. 8–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "Production Process of Silicon". www.simcoa.com.au. Simcoa Operations. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "Reaching kerf loss below 100 μm by optimizations" (PDF). Fraunhofer ISE, 24th European PV Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition. September 2009.

- ^ "Silicon kerf loss recycling". HZDR - Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf. 4 April 2014.

- ^ "Life Cycle Assessment of Future Photovoltaic Electricity Production from Residential-scale Systems Operated in Europe". IEA-PVPS. 13 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Solar Photovoltaics, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, 2012, 1–2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Krebs, F. C. (2009). "Fabrication and processing of polymer solar cells: a review of printing and coating techniques". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 93 (4): 394–412. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2008.10.004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yue, D., You, F. & Darling, S. B. (2014). "Domestic and overseas manufacturing scenarios of silicon-based photovoltaics: Life cycle energy and environmental comparative analysis". Solar Energy. 105: 669–678. Bibcode:2014SoEn..105..669Y. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2014.04.008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Gaidajis, G. & Angelakoglou, K. (2012). "Environmental performance of renewable energy systems with the application of life-cycle assessment: a multi-Si photovoltaic module case study". Civil Engineering and Environmental Systems. 29 (4): 231–238. doi:10.1080/10286608.2012.710608. S2CID 110058349.

- ^ Photovoltaics Report. (Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, ISE, 2015).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goe, M. & Gaustad, G. (2014). "Strengthening the case for recycling photovoltaics: An energy payback analysis". Applied Energy. 120: 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.01.036.

- ^ "Solar PV Modules". www.targray.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Kosasih, Felix Utama; Rakocevic, Lucija; Aernouts, Tom; Poortmans, Jef; Ducati, Caterina (11 December 2019). "Electron Microscopy Characterization of P3 Lines and Laser Scribing-Induced Perovskite Decomposition in Perovskite Solar Modules". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 11 (49): 45646–45655. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b15520. PMID 31663326.

- ^ Di Giacomo, Francesco; Castriotta, Luigi A.; Kosasih, Felix U.; Di Girolamo, Diego; Ducati, Caterina; Di Carlo, Aldo (20 December 2020). "Upscaling Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells: Optimization of Laser Scribing for Highly Efficient Mini-Modules". Micromachines. 11 (12): 1127. doi:10.3390/mi11121127. PMC 7767295. PMID 33419276.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matteocci, Fabio; Vesce, Luigi; Kosasih, Felix Utama; Castriotta, Luigi Angelo; Cacovich, Stefania; Palma, Alessandro Lorenzo; Divitini, Giorgio; Ducati, Caterina; Di Carlo, Aldo (17 July 2019). "Fabrication and Morphological Characterization of High-Efficiency Blade-Coated Perovskite Solar Modules". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 11 (28): 25195–25204. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b05730. PMID 31268662.

- ^ "Thin Film Photovoltaics". www.fsec.ucf.edu. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Best Research Cell Efficiences. nrel.gov (16 September 2019). Retrieved on 31 October 2019.

- ^ Nikolaidou, Katerina; Sarang, Som; Ghosh, Sayantani (2019). "Nanostructured photovoltaics". Nano Futures. 3 (1): 012002. Bibcode:2019NanoF...3a2002N. doi:10.1088/2399-1984/ab02b5.

- ^ Eisenberg, D. A., Yu, M., Lam, C. W., Ogunseitan, O. A. & Schoenung, J. M. (2013). "Comparative alternative materials assessment to screen toxicity hazards in the life cycle of CIGS thin film photovoltaics". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 260: 534–542. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.06.007. PMID 23811631.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Kim, H. C., Fthenakis, V., Choi, J. K. & Turney, D. E. (2012). "Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of thin-film photovoltaic electricity generation". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 16: S110–S121. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2011.00423.x. S2CID 153386434.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Werner, Jürgen H.; Zapf-Gottwick, R.; Koch, M.; Fischer, K. (2011). Toxic substances in photovoltaic modules. Proceedings of the 21st International Photovoltaic Science and Engineering Conference. 28. Fukuoka, Japan.

- ^ Brown, G. F. & Wu, J. (2009). "Third generation photovoltaics". Laser & Photonics Reviews. 3 (4): 394–405. Bibcode:2009LPRv....3..394B. doi:10.1002/lpor.200810039.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Celik, Ilke; Song, Zhaoning; Cimaroli, Alexander J.; Yan, Yanfa; Heben, Michael J.; Apul, Defne (2016). "Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of perovskite PV cells projected from lab to fab". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 156: 157–69. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2016.04.037.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Espinosa, N., Serrano-Luján, L., Urbina, A. & Krebs, F. C. (2015). "Solution and vapour deposited lead perovskite solar cells: Ecotoxicity from a life cycle assessment perspective". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 137: 303–310. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2015.02.013.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gong, J., Darling, S. B. & You, F. (2015). "Perovskite photovoltaics: life-cycle assessment of energy and environmental impacts". Energy & Environmental Science. 8 (7): 1953–1968. doi:10.1039/C5EE00615E.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Celik, I., Mason, B. E., Phillips, A. B., Heben, M. J., & Apul, D. S. (2017). Environmental Impacts from Photovoltaic Solar Cells Made with Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Environmental Science & Technology.

- ^ Agboola, A. E. Development and model formulation of scalable carbon nanotube processes: HiPCO and CoMoCAT process models;Louisiana State University, 2005.

- ^ Wadia, C., Alivisatos, A. P. & Kammen, D. M. (2009). "Materials Availability Expands the Opportunity for Large-Scale Photovoltaics Deployment". Environmental Science and Technology. 43 (6): 2072–2077. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.2072W. doi:10.1021/es8019534. PMID 19368216.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Alharbi, Fahhad; Bass, John D.; Salhi, Abdelmajid; Alyamani, Ahmed; Kim, Ho-Cheol; Miller, Robert D. (2011). "Abundant non-toxic materials for thin film solar cells: Alternative to conventional materials". Renewable Energy. 36 (10): 2753–2758. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.03.010.