Physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence

The physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence spans from its original drafting in 1776 into the discovery of historical documents in modern time. This includes a number of drafts, handwritten copies, and published broadsides. The Declaration of Independence states that the thirteen "United Colonies", "are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States"; and were no longer a part of the British Empire.

Drafts and pre-publication copies[]

Composition Draft[]

The earliest known draft of the Declaration of Independence is a fragment known as the "Composition Draft".[1] The draft, written in July 1776, is in the handwriting of Thomas Jefferson, principal author of the Declaration. It was discovered in 1947 by historian Julian P. Boyd in the Jefferson papers at the Library of Congress. Boyd was examining primary documents for publication in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson when he found the document, a piece of paper that contains a small part of the text of the Declaration, as well as some unrelated notes made by Jefferson.[2] Prior to Boyd's discovery, the only known draft of the Declaration had been a document known as the Rough Draft. The discovery confirmed speculation by historians that Jefferson must have written more than one draft of the text.[2]

Many of the words from the Composition Draft were ultimately deleted by Congress from the final text of the Declaration. George Mason was a Virginian politician and wrote the Virginia Declaration of Rights in May-June 1776. Mason wrote something very similar to Jefferson's first section of the declaration. Its opening was:

Section 1. That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.[3]

Phrases from the fragment to survive the editing process include "acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our separation" and "hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends".[2]

Forensic examination has determined that the paper of the Composition Draft and the paper of the Rough Draft were made by the same manufacturer.[4] In 1995, conservators at the Library of Congress undid some previous restoration work on the fragment and placed it in a protective mat. The document is stored in a cold storage vault. When it is exhibited, the fragment is placed in a temperature and humidity controlled display case.[4]

Rough Draft[]

Thomas Jefferson preserved a four-page draft that late in life he called the "original Rough draft".[5][6] Known to historians as the Rough Draft, early students of the Declaration believed that this was a draft written alone by Jefferson and then presented to the Committee of Five drafting committee. Some scholars now believe that the Rough Draft was not actually an "original Rough draft", but was instead a revised version completed by Jefferson after consultation with the committee.[5] How many drafts Jefferson wrote prior to this one, and how much of the text was contributed by other committee members, is unknown.

Jefferson showed the Rough Draft to John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, and perhaps other members of the drafting committee. Adams and Franklin made a few more changes.[5] Franklin, for example, may have been responsible for changing Jefferson's original phrase "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable" to "We hold these truths to be self-evident."[7] Jefferson incorporated these changes into a copy that was submitted to Congress in the name of the committee. Jefferson kept the Rough Draft and made additional notes on it as Congress revised the text. He also made several copies of the Rough Draft without the changes made by Congress, which he sent to friends, including Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe, after July 4. At some point in the process, Adams also wrote out a copy.[5]

Fair Copy[]

In 1823, Jefferson wrote a letter to James Madison in which he recounted the drafting process. After making alterations to his draft as suggested by Franklin and Adams, he recalled that "I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the Committee, and from them, unaltered, to Congress."[8] If Jefferson's memories were correct, and he indeed wrote out a fair copy which was shown to the drafting committee and then submitted to Congress on June 28, this document has not been found.[9] "If this manuscript still exists," wrote historian Ted Widmer, "it is the holy grail of American freedom."[10]

The Fair Copy was presumably marked up by Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Continental Congress, while Congress debated and revised the text.[11] This document was the one that Congress approved on July 4, making it what Boyd called the first "official" copy of the Declaration. The Fair Copy was sent to John Dunlap to be printed under the title "A Declaration by the Representatives of the united states of america, in General Congress assembled". Boyd argued that if a document was signed in Congress on July 4, it would have been the Fair Copy, and probably would have been signed only by John Hancock with his signature being attested by Thomson.[12]

The Fair Copy may have been destroyed in the printing process,[13] or destroyed during the debates in accordance with Congress's secrecy rule. Author Wilfred J. Ritz speculates that the Fair Copy was immediately sent to the printer so that copies could be made for each member of Congress to consult during the debate, and that all of these copies were then destroyed to preserve secrecy.[14]

Broadsides[]

The Declaration was first published as a broadside printed by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. One broadside was pasted into Congress's journal, making it what Boyd called the "second official version" of the Declaration.[15] Dunlap's broadsides were distributed throughout the thirteen states. Upon receiving these broadsides, many states issued their own broadside editions.[16]

Dunlap broadside[]

The Dunlap broadsides are the first published copies of the Declaration of Independence, printed on the night of July 4, 1776. It is unknown exactly how many broadsides were originally printed, but the number is estimated at about 200.[17] John Hancock's eventually famous signature is not on this document, but his name appears in large type under "Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress", with secretary Charles Thomson listed as a witness ("Attest").

On July 4, 1776, Congress ordered the same committee charged with writing the document to "superintend and correct the press", that is, supervise the printing. Dunlap, an Irish immigrant then 29 years old, was tasked with the job; he apparently spent much of the night of July 4 setting type, correcting it, and running off the broadside sheets.[18]

"There is evidence it was done quickly, and in excitement—watermarks are reversed, some copies look as if they were folded before the ink could dry and bits of punctuation move around from one copy to another", according to Ted Widmer, author of Ark of the Liberties: America and the World. "It is romantic to think that Benjamin Franklin, the greatest printer of his day, was there in Dunlap's shop to supervise, and that Jefferson, the nervous author, was also close at hand."[18] John Adams later wrote, "We were all in haste."[18] The Dunlap broadsides were sent across the new United States over the next two days, including to Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, who directed that the Declaration be read to the troops on July 9. Another copy was sent to England.[18]

In 1949, 14 copies of the Dunlap broadside were known to exist.[16] The number had increased to 21 by 1975.[19] There were 24 known copies of the Dunlap broadside in 1989, when a 25th broadside was discovered[20] behind a painting bought for four dollars at a flea market.

On July 2, 2009, it was announced that a 26th Dunlap broadside was discovered in The National Archives in Kew, England. It is currently unknown how this copy came to the archive, but one possibility is that it was captured from an American coastal ship intercepted during the War of Independence.[21][22]

List of extant Dunlap broadsides[]

| # | Location | Owner | Provenance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New Haven, Connecticut | Beinecke Library, Yale University | [18] | |

| 2 | Bloomington, Indiana | Lilly Library, Indiana University | Previous owner was Henry N. Flynt of Greenwich, Connecticut. | [18] |

| 3 | Portland, Maine | Maine Historical Society | Given to the society in 1893 at the bequest of John S. H. Fogg. | [18] |

| 4 | Chicago, Illinois | Chicago Historical Society | Signed by John Steward (1747–1829) of Goshen, New York; sold July 2, 1975, at auction, by Christie's, London; later sold to the Chicago Historical Society. | [18] |

| 5 | Baltimore, Maryland | Maryland Historical Society | Fragment of upper left area of the document, including the first 36 lines. | [18] |

| 6 | Boston, Massachusetts | Massachusetts Historical Society | [18] | |

| 7 | Cambridge, Massachusetts | Houghton Library, Harvard University | Donated in 1947 by Carleton R. Richmond. | [18] |

| 8 | Williamstown, Massachusetts | Williams College | Previously owned by the Wood family; sold at auction, April 22, 1983, by Christie's, New York. | [18] |

| 9 | Princeton, New Jersey | Scheide Library, Firestone Library, Princeton University | Currently owned by William R. Scheide; bought by John H. Scheide from A. S. W. Rosenbach. | [18] |

| 10 | New York, New York (last known location) |

Private collector | Sold by the New-York Historical Society to a private collector in the United States, sometime between 1993 and 2008. | [18][23] |

| 11 | New York, New York | New York Public Library | [18] | |

| 12 | New York, New York | Morgan Library | Once owned by the Chew family; sold April 1, 1982, at auction at Christie's, New York. | [18] |

| 13 | Exeter, New Hampshire | American Independence Museum | Copy discovered in 1985 in the Ladd-Gilman House in Exeter. | [18] |

| 14 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | American Philosophical Society | Acquired from the Library of Congress in 1901 in a trade for Benjamin Franklin's Passy imprint of The Boston Independent Chronicle "Supplement." | [18] |

| 15 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Historical Society of Pennsylvania | Fragment including the first 32 lines, thought to be likely an uncorrected proof, from the Frank M. Etting collection; Etting asserted it was this document that had been read in public. However, Charles Henry Hart wrote in 1900: "The endorsement is in the handwriting of the late Frank M. Etting, who died insane, one of the most inexact and inaccurate of collectors." | [18] |

| 16 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence National Historical Park | Previously owned by Col. John Nixon, appointed by the sheriff of Philadelphia to read the Declaration of Independence to the public on July 8, 1776, in the State House yard; presented to the park by his heirs in 1951. | [18] |

| 17 | Dallas, Texas | Dallas Public Library | "The Leary Copy" discovered in 1968 amid the stock of Leary's Book Store of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in a crate that had been unopened since 1911. Ira G. Corn Jr. and Joseph P. Driscoll of Dallas bought the manuscript on May 7, 1969. A group of 17 people later sold it to the Dallas city government. | [18] |

| 18 | Charlottesville, Virginia | University of Virginia | 1/2. Found in 1955 in an attic in Albany, New York, where it had been used to wrap other papers. Bought by Charles E. Tuttle Company of Rutland, Vermont; later sold to David Randall, who sold it in 1956 to the university. | [18] |

| 19 | Charlottesville, Virginia | University of Virginia | 2/2. "The H. Bradley Martin Copy"; exhibited at the Grolier Club in 1974; sold on January 31, 1990 to Albert H. Small, who gave it to the university. | [18] |

| 20 | Washington, D.C. | Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division | [18] | |

| 21 | Washington, D.C. | Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division, Washington Papers | Fragment copy with 54 lines; thought to be the copy George Washington read to the troops on July 9, 1776, in New York. | [18] |

| 22 | Washington, D.C. | National Archives | Inserted into the Continental Congress manuscript journal, previously attached with a seal. | [18] |

| 23 | Roving copy | Norman Lear | Found in the back of a picture frame bought at a yard sale for $4.00 at an Adamstown, Pennsylvania flea market; now owned by a consortium which includes Norman Lear; sold in 2000 for $8.14 million; previously sold for $2.42 million on June 4, 1991. | [24][25] |

| 24 | London, United Kingdom | The National Archives, Colonial Office Papers | General William Howe and Vice Admiral Richard Howe from the flagship Eagle, off Staten Island, sent this copy with a letter dated August 11, 1776, which states, "A printed copy of this Declaration of Independency came accidentally to our hands a few days after the dispatch of the Mercury packet, and we have the honor to enclose it." | [18] |

| 25 | London, United Kingdom | The National Archives, Admiralty Papers | Vice Admiral Richard Howe sent this copy from the flagship Eagle, then "off Staten Island" with a letter dated July 28, 1776. | [18] |

| 26 | London, United Kingdom | The National Archives, Colonial Office Papers | Discovered in box of documents in 2008. Exact provenance is currently unknown. | [21][22] |

Goddard broadside[]

In January 1777, Congress commissioned Mary Katherine Goddard to print a new broadside that, unlike the Dunlap broadside, lists the signers of the Declaration.[26][27] With the publication of the Goddard broadside, the public learned for the first time who had signed the Declaration.[27] One of the eventual signers of the Declaration, Thomas McKean, is not listed on the Goddard broadside, suggesting that he had not yet added his name to the signed document at that time.

In 1949, nine Goddard broadsides were known to still exist. The reported locations of those copies at that time were these:[28]

- Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.)

- Connecticut State Library (Hartford, Connecticut)

- Library of the late John W. Garrett

- Maryland Hall of Records (Annapolis, Maryland)

- Maryland Historical Society (Baltimore, Maryland)

- Massachusetts Archives (Dorchester, Massachusetts)

- New York Public Library (New York, New York)

- Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- Rhode Island State Archives (Providence, Rhode Island)

Other broadsides[]

In addition to the broadsides authorized by Congress, many states and private printers also issued broadsides of the Declaration, using the Dunlap broadside as a source. In 1949, an article in the Harvard Library Review surveyed all the broadsides known to exist at that time and found 19 editions or variations of editions, including the Dunlap and Goddard printings. The author was able to locate 71 copies of these various editions.[16]

A number of copies have been discovered since that time. In 1971, a copy of a rare four-column broadside probably printed in Salem, Massachusetts was discovered in Georgetown University's Lauinger Library.[29] In 2010, there were media reports that a copy of the Declaration was located in Shimla, India, having been discovered sometime during the 1990s. The type of copy was not specified.[30]

Parchment copies[]

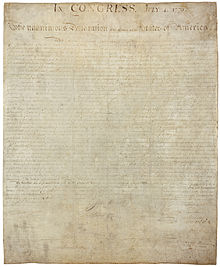

The Matlack Declaration[]

The copy of the Declaration that was signed by Congress is known as the engrossed or parchment copy. This copy was probably handwritten by clerk Timothy Matlack, and given the title of "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America".[31] This was specified by the Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776:

Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America," and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.[32]

Throughout the Revolutionary War, the engrossed copy was moved with the Continental Congress,[33] which relocated several times to avoid the British army. In 1789, after creation of a new government under the United States Constitution, the engrossed Declaration was transferred to the custody of the secretary of state.[33] The document was evacuated to Virginia when the British attacked Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812.[33]

After the War of 1812, the symbolic stature of the Declaration steadily increased even though the engrossed copy's ink was noticeably fading.[17] In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned printer William J. Stone to create an engraving essentially identical to the engrossed copy.[33] Stone's engraving was made using a wet-ink transfer process, where the surface of the document was moistened, and some of the original ink transferred to the surface of a copper plate, which was then etched so that copies could be run off the plate on a press. When Stone finished his engraving in 1823, Congress ordered 200 copies to be printed on parchment.[33] Because of poor conservation of the engrossed copy through the 19th century, Stone's engraving, rather than the original, has become the basis of most modern reproductions.[34] 48 of the documents produced by Stone are known to still exist as of 2021; one was sold at auction for $4,420,000 on July 1, 2021.[35]

From 1841 to 1876, the engrossed copy was publicly displayed on a wall opposite a large window at the Patent Office building in Washington, D.C. Exposed to sunlight and variable temperature and humidity, the document faded badly. In 1876, it was sent to Independence Hall in Philadelphia for exhibit during the Centennial Exposition, which was held in honor of the Declaration's 100th anniversary, and then returned to Washington the next year.[33] In 1892, preparations were made for the engrossed copy to be exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but the poor condition of the document led to the cancellation of those plans and the removal of the document from public exhibition.[33] The document was sealed between two plates of glass and placed in storage. For nearly 30 years, it was exhibited only on rare occasions at the discretion of the Secretary of State.[36]

In 1921, custody of the Declaration, along with the United States Constitution, was transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress. Funds were appropriated to preserve the documents in a public exhibit that opened in 1924.[37] After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the documents were moved for safekeeping to the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox in Kentucky, where they were kept until 1944.[38]

For many years, officials at the National Archives believed that they, rather than the Library of Congress, should have custody of the Declaration and the Constitution. The transfer finally took place in 1952, and the documents, along with the Bill of Rights, are now on permanent display at the National Archives in the "Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom". Although encased in helium, by the early 1980s the documents were threatened by further deterioration. In 2001, using the latest in preservation technology, conservators treated the documents and transferred them to encasements made of titanium and aluminum, filled with inert argon gas.[39] They were put on display again with the opening of the remodeled National Archives Rotunda in 2003.[40]

The Sussex Declaration[]

On April 21, 2017, the Declaration Resources Project at Harvard University announced that a second parchment manuscript copy had been discovered at West Sussex Record Office in Chichester, England.[41] Named the "Sussex Declaration" by its finders, Danielle Allen and Emily Sneff, it differs from the National Archives copy (which the finders refer to as the "Matlack Declaration") in that the signatures on it are not grouped by States. How it came to be in England is not yet known, but the finders believe that the randomness of the signatures points to an origin with signatory James Wilson, who had argued strongly that the Declaration was made not by the States but by the whole people.[42][43] The Sussex Declaration was probably brought to Sussex, England by Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, known as the 'radical duke'.[44]

The finders identify the Sussex Declaration as a transcription of the Matlack Declaration, probably made between 1783 and 1790 and likely in New York City or possibly Philadelphia. They propose that the Sussex Declaration "descended from the Matlack Declaration, and it (or a copy) served, before disappearing from view, as a source text for both the 1818 Tyler engraving and the 1836 Bridgham engraving".[45]

See also[]

- The Pennsylvania Evening Post, the first newspaper to print the Declaration, on July 6, 1776

- Syng inkstand, used by the delegates to sign the Declaration

- Printing of the United States Constitution

References[]

- ^ Boyd, Papers of Jefferson, 1:421.

- ^ a b c Gerald Gawalt (July 1999). "Jefferson and the Declaration: Updated Work Studies Evolution of Historic Text". Information Bulletin. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ see "Virginia Declaration of Rights"

- ^ a b Mark Roosa (July 1999). "Preservation Corner: Piecing Together Fragments of History". Information Bulletin. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Boyd, "Lost Original", 446.

- ^ Kaufman, Mark (July 2, 2010). "Jefferson changed 'subjects' to 'citizens' in Declaration of Independence". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ^ Becker, Declaration of Independence, 142 note 1. Boyd (Papers of Jefferson, 1:427–28) casts doubt on Becker's belief that the change was made by Franklin.

- ^ Maier, 100.

- ^ Becker, 139.

- ^ Widmer.

- ^ Boyd, "Lost Original", 449.

- ^ Boyd, "Lost Original", 450.

- ^ Boyd, "Lost Original", 448–50.

- ^ Ritz, Wilfred J. (October 1992). "From the Here of Jefferson's Handwritten Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence to the There of the Printed Dunlap Broadside". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 116, no. 4. pp. 499–512.

- ^ Boyd, "Lost Original", 452.

- ^ a b c Walsh, Michael J. "Contemporary Broadside Editions of the Declaration of Independence". Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume III, Number 1 (Winter 1949), 31–43.

- ^ a b Phillips, Heather A., Safety and Happiness; The Paradox of the Declaration of Independence. The Early America Review, Vol. VII No. 4. http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2007_summer_fall/preserving-documents.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Illustration for Widmer, Ted, "Looking for Liberty", oped commentary article, The New York Times, July 4, 2008, accessed July 7, 2008

- ^ Boyd, "Lost Original", 453.

- ^ "Hidden Copy of Declaration of Independence to be Auctioned". The Washington Post. April 3, 1991. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Katz, Gregory (July 2, 2009). "Rare Copy of Declaration of Independence Found". Huffington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Rare copy of United States Declaration of Independence found in Kew". The Daily Telegraph. July 3, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (4 June 1993). "Sotheby's Challenged In Selling Declaration". The New York Times.

- ^ "Projects - The Norman Lear Center".

- ^ McSorley, Joshua. "Reliam: Maintenance Page".

- ^ "The Declaration of Independence: A History". Charters of Freedom. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Ann Marie Dube (May 1996). "The Declaration of Independence". A Multitude of Amendments, Alterations and Additions: The Writing and Publicizing of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution of the United States. National Park Service. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ Ann Marie Dube (May 1996). "Appendix D". A Multitude of Amendments, Alterations and Additions: The Writing and Publicizing of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution of the United States. National Park Service. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Heller, Chris (July 6, 2010). "Lauinger Library owns a very expensive document". The Georgetown Voice. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Copy of US Declaration found in Shimla". The Times of India. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ This copy of the Declaration renders the "u" in United States in small case, "united States", one of several variations in capitalization and punctuation that historians Boyd and Becker believed to be of no significance; Boyd, Evolution, 25–26. In his notes and Rough Draft, Jefferson capitalized variously as "United states" (Boyd, Papers of Jefferson, 1:315) and "United States" (ibid., 1:427).

- ^ "Journals of the Continental Congress --FRIDAY, JULY 19, 1776".

- ^ a b c d e f g Gustafson, "Travels of the Charters of Freedom".

- ^ National Archives.

- ^ "Copy of US Declaration of Independence found in Scottish attic". STV News. 1 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Malone, Story of the Declaration, 257.

- ^ "Charter of Liberties Finds a Home". New York Times Magazine. April 6, 1924. p. SM7.

- ^ Malone, Story of the Declaration, 263.

- ^ "National Archives Press Release". Archives.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ "A New Era Begins for the Charters of Freedom". Archives.gov. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Wang, Amy B. (April 24, 2017). "A rare copy of the Declaration of Independence has been found — in England". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Yuhas, Alan (April 22, 2017). "Rare parchment copy of US Declaration of Independence found in England". The Guardian. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ "The Sussex Declaration". Declaration Resources Project. Harvard University. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ "Rare Parchment Amerian Declaration of Independence Found in Chichester Records Office". 24 April 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Allen, Danielle; Sneff, Emily (April 20, 2017). "The Sussex Declaration: Dating the Parchment Manuscript of the Declaration of Independence Held at the West Sussex Record Office (Chichester, UK) (Under final revision and preparation for publication at Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America)" (PDF). Retrieved April 22, 2017.

Bibliography[]

- Becker, Carl (1970) [Originally published 1922]. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas at Google Books (Revised ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-70060-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|others= - Boyd, Julian P. (1999) [Originally published 1945]. Gawalt, Gerard W. (ed.). The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text (Revised ed.). University Press of New England. ISBN 0-8444-0980-4.

- Boyd, Julian P. (1950). Boyd, Julian P. (ed.). The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press.

- Boyd, Julian P. (October 1976). The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 100. pp. 438–467.

- Hazelton, John H. (1970) [Originally published 1906]. The Declaration of Independence: Its History. Physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence at Google Books. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-71987-8.

{{cite book}}: External link in|others= - Maier, Pauline (1997). American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-45492-6.

- Malone, Dumas (1975). The Story of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Phillips, Heather A. Safety and Happiness; The Paradox of the Declaration of Independence. The Early America Review. Vol. VII.

Further reading[]

- Goff, Frederick R. The John Dunlap Broadside: the first printing of the Declaration of Independence. Washington: Library of Congress, 1976.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Draft of the United States Declaration of Independence. |

- "Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents" from the Library of Congress

- "Declaration Resources Project". Harvard University.

- Three copies of the Dunlap Broadside are held by the UK National Archives.

- The Declaration of Independence Home Page from Duke University features the evolution of the text through the drafts

- PBS/NOVA: The Preservation and History of the Declaration

- 1776 in the British Empire

- 1776 in the United States

- Documents of the American Revolution

- The National Archives (United Kingdom)

- United States Declaration of Independence