Pine Tar Incident

The Pine Tar Incident (also known as the Pine Tar Game) was a controversial incident in 1983 during an American League baseball game played between the Kansas City Royals and New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium in New York City on July 24, 1983 (a Sunday).

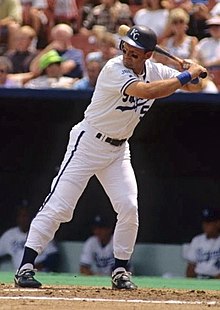

With his team trailing 4–3 in the top half of the ninth inning and two out, Royals' third baseman George Brett hit a two-run home run to give his team the lead. However, Yankees manager Billy Martin, who had noticed a large amount of pine tar[1] on Brett's bat, requested that the umpires inspect his bat. The umpires ruled that the amount of pine tar on the bat exceeded the amount allowed by rule, nullified Brett's home run, and called him out. As Brett was the third out in the ninth inning with the home team in the lead, the game ended with a Yankees win.[2][3][4][5][6]

The Royals protested the game, and American League president Lee MacPhail upheld their protest. MacPhail ordered that the game be continued from the point of Brett's home run.[7][8][9] The game was resumed 25 days later on August 18, and officially ended with the Royals winning 5–4.[6][10]

Incident[]

Playing at New York's Yankee Stadium, the Royals were trailing 4–3 with two outs in the top of the ninth and U L Washington on first base. George Brett came to the plate and reliever Dale Murray was replaced by closer Rich "Goose" Gossage. After fouling off the first pitch to the left, Brett connected on a high strike and put it well into the right field stands for a two-run home run and a 5–4 lead.[2][3][6]

As Brett crossed the plate, however, New York manager Billy Martin approached rookie home plate umpire Tim McClelland and requested Brett's bat be examined. Before the game, Martin and other members of the Yankees had noticed the amount of pine tar used by Brett, but Martin had chosen not to say anything until it was strategically useful to do so.[11] Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles recalled a similar incident involving Thurman Munson in a 1975 game against the Minnesota Twins.[12] In Nettles' autobiography Balls, Nettles claims that he actually informed Martin of the pine tar rule, as Nettles had previously undergone the same scrutiny with his own bat while with the Twins.

With Brett watching from the dugout, McClelland and the rest of the umpiring crew, Drew Coble, Joe Brinkman, and Nick Bremigan, inspected the bat. Measuring the bat against the width of home plate (17 inches or 43 centimetres), they determined that the amount of pine tar on the bat's handle exceeded that allowed by Rule 1.10(c) of the Major League Baseball rule book, which read that "a bat may not be covered by such a substance more than 18 inches [46 cm] from the tip of the handle." At the time, such a hit was defined in the rules as "an illegally batted ball," and under the terms of the then-existing provisions of Rule 6.06, any batter who hit an illegally batted ball was automatically called out. The umpires concluded that Brett's home run was disallowed under this interpretation, and he was out, thus ending the game.

McClelland searched for Brett in the visitors' dugout, pointed at him with the bat, and signaled that he was out, handing the Yankees a 4–3 win. An enraged Brett ran out of the dugout and confronted McClelland, requiring him to be physically restrained by his manager Dick Howser, several of his teammates, and crew chief Joe Brinkman. (As one commentator noted, "Brett had the ignominious distinction of hitting a game-losing home run." Ironically, the call was announced just after the broadcaster's prediction. [13]) Despite the furious protests of Brett and Howser, McClelland's ruling stood.[2][3]

He's out! Look at this!...He is out, and having to be forcibly restrained from hitting plate umpire Tim McClelland. And the Yankees have won the ball game 4 to 3! Brett is called out for using an...illegal substance on the bat!

Protest and reversal[]

The Royals protested the game. Four days later, American League president Lee MacPhail upheld the Royals' protest. In explaining his decision, MacPhail noted that the "spirit of the restriction" on pine tar on bats was based not on the fear of unfair advantage, but simple economics; any contact with pine tar would discolor the ball, render it unsuitable for play, and require that it be discarded and replaced—thus increasing the home team's cost of supplying balls for a given game. MacPhail ruled that Brett had not violated the spirit of the rules nor deliberately "altered [the bat] to improve the distance factor".[8][9]

MacPhail's ruling followed precedent established after a protest in 1975 of the September 7 game played between the Royals and the California Angels.[14] In that game, the umpiring crew had declined to negate one of John Mayberry's home runs for excessive pine tar use. MacPhail, who also heard this protest, upheld the umpires' decision with the view that the intent of the rule was to prevent baseballs from being discolored during game play and that any discoloration that may have occurred to a ball leaving the ballpark did not affect the game's competitive balance.

MacPhail thus restored Brett's home run and ordered the game resumed with two outs in the top of the ninth inning with the Royals leading 5–4. Although MacPhail ruled that Brett's home run counted, he retroactively ejected Brett for his outburst against McClelland. He also ejected Howser and coach Rocky Colavito for arguing with the umpires, and Royals pitcher Gaylord Perry for giving the bat to the bat boy so he could hide it in the clubhouse.

Conclusion[]

Strategic maneuvering[]

The Yankees resisted the resumption of the game, and waited until near the end of the season to agree to it, to see if the game would have an effect on the standings or should be forfeited.[15]

After ordering the resumption of gameplay, MacPhail and other league officials held a strategy session to anticipate tricks the Yankees might use to prevent the game from continuing.[16]

Legal battle[]

For the resumption of the game, the Yankees announced that they would charge non-season-ticket holders a $2.50 admission fee (equivalent to $6.5 in 2020) to attend. Two lawsuits were filed against the Yankees and Bronx Supreme Court (trial court) Justice Orest Maresca issued an injunction, also requested by the Yankees, preventing the game from being resumed until the lawsuits were litigated.[15] Maresca also cited the Yankees' expressed concerns about security problems resulting from confusion over admission to the game.[17]

That injunction was immediately appealed by the American League and was overturned by Supreme Court Appellate Division Justice Joseph Sullivan. The Royals, who were in flight during that day's legal battles, did not know that the game would be played until they arrived at Newark Airport.[15]

The Yankees finally agreed to allow admission for the game's conclusion to anybody with a ticket stub from the July 24 game at no additional charge.[15]

Resumption of play[]

On August 18 (a scheduled off-day for both teams), the game was resumed from the point of Brett's home run, with about 1,200 fans in attendance. On paper, the scoring of the incident reads as follows: a home run for George Brett, scoring Brett and U L Washington; on the play, Brett, Perry, coach Colavito, and manager Howser were ejected; game suspended, with two outs in the top of the ninth.[15]

Brett himself did not attend the game, and after the team landed in New Jersey, he departed directly for Baltimore, where the Royals were scheduled to play the next day[15]—although other sources indicate Brett was waiting at Newark International Airport for the rest of the team, passing the time playing hearts.[18]

A still-furious Martin symbolically protested the continuation of the game by putting pitcher Ron Guidry in center field and first baseman Don Mattingly at second base.[19] Mattingly was ostensibly placed at second because the second baseman from the July 24 game, Bert Campaneris, was injured, and Guidry replaced original center-fielder Jerry Mumphrey, who had since been traded to the Houston Astros. By keeping Mattingly and Guidry in the game and filling in at needed positions, Martin was able to avoid "wast[ing] a possible pinch hitter or runner."[19]

Mattingly, a lefty, became a rare Major League southpaw second baseman; no left-hander had played second base or shortstop in a big-league game since Cleveland Indians left-handed pitcher Sam McDowell was switched from pitcher to second base for one batter in a game in 1970 against the Washington Senators in order to avoid facing Senators slugger Frank Howard.[20][21]

Base touching affidavit[]

Before the first pitch to Hal McRae (who followed Brett in the lineup), Yankee pitcher George Frazier threw the first ball to first base to challenge Brett's home run on the grounds that Brett had not touched first base.[19] Umpire Tim Welke (given incorrectly in some sources as Tim McClelland, the original home plate umpire[19]) called safe, even though he had not officiated the July 24 game and seen Brett touch the bases.[15] Frazier then threw to second, claiming that the base was touched by neither Brett nor U L Washington, the other player scoring on the home run, but umpire Dave Phillips signaled safe.[19]

Martin went on the field to protest, and Phillips, chief of the new crew, pulled out a notarized affidavit, produced by MacPhail's administrative assistant Bob Fishel, signed by all four umpires from July 24 indicating that Brett had touched every base.[19] Fishel had anticipated that Martin would protest the base touching and the umpires' personal knowledge of it.[16]

Martin claimed to be surprised by the affidavit because he had spoken by telephone to the first base umpire from July 24, Drew Coble, who had said that he wasn't looking at first base when Brett had circled first base.[19] As he exited, the umpires announced that the game was being played under protest by the Yankees.[15]

Resumed game play[]

Frazier struck out McRae to end the top of the ninth, 25 days after the inning began. Royals' closer Dan Quisenberry retired New York in order for the save, preserving the Royals' 5–4 win.[15]

The loss placed the Yankees in fifth place, three and a half games out of first.[15] Neither team advanced to the postseason.

Quisenberry gained his league-leading 33rd save, while Mattingly lost a 25-game hitting streak.[18]

Aftermath[]

The bat is currently on display in the Baseball Hall of Fame, where it has been since 1987. During a broadcast of Mike & Mike in the Morning, ESPN analyst Tim Kurkjian stated that Brett used the bat for a few games after the incident until being cautioned that the bat would be worthless if broken. Brett sold the bat to famed collector and then-partial owner of the Yankees, Barry Halper, for $25,000 (equivalent to $55,000 in 2019),[22] had second thoughts, repurchased the bat for the same amount, and then donated the bat to the Hall of Fame.

The home-run ball was caught by journalist Ephraim Schwartz, who sold it and his game ticket stub to Halper for $500 (equivalent to $1,300 in 2020) plus 12 Yankees tickets.[23][24] Halper also acquired the signed business card of Justice Orest V. Maresca, who had issued the injunction, and the can of Oriole Pine Tar Brett had used on the bat. Gossage later signed the pine-tar ball, "Barry, I threw the fucking thing".[25] The winning pitcher for the Royals was reliever Mike Armstrong, who went 10–7 that year in 58 appearances, notching career highs in wins and games. Armstrong said in a 2006 interview that, as the Royals were leaving for the airport after the resumed game, an angry Yankees fan threw a brick from an overpass at Kansas City's bus, cracking its windshield.

"It was wild to go back to New York and play these four outs in a totally empty stadium," Armstrong said in 2006. "I'm dressed in the uniform, and nobody's there."[26]

Before a game against the Yankees at Kauffman Stadium on May 5, 2012, the Royals gave each fan who attended the game a replica baseball bat designed to look like the one Brett used with the pine tar.[27]

As part of the Royals' fiftieth season in 2018, before a game against the Yankees at Kauffman Stadium on May 19, the Royals gave 18,000 fans who attended the game a George Brett Pine Tar bobblehead to celebrate the incident and Royals victory. It depicts Brett, after his home run was nullified, rushing at the umpires in anger.[28]

In 2010, Major League Baseball amended the official rules with a comment on rule 1.10(c) clarifying the consequences of using excessive pine tar on a bat. The comment codifies the interpretation of the rule issued by McPhail in his reversal:

If no objections are raised prior to a bat’s use, then a violation of Rule 1.10(c) on that play does not nullify any action or play on the field and no protests of such play shall be allowed.[29]

Scoring[]

| Pitcher New York Yankees |

Batter Kansas City Royals |

Result (outs in bold) |

Score Royals – Yankees |

Date played |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dale Murray (R) | Don Slaught (R) | Ground out to shortstop | 3–4 | July 24 |

| Pat Sheridan (L) | Line out to first baseman | |||

| U L Washington (S) | Single up the middle | |||

| Rich Gossage (R) | George Brett (L) | Home run to right | 5–4 | |

| George Frazier (R) | Hal McRae (R) | Strikeout |

In popular culture[]

In 1983, folk and "hillbilly" artist Red River Dave McEnery released "The Pine-Tarred Bat (The Ballad of George Brett)" on Longhorn Records.[30]

Country music artist C. W. McCall dedicated the 1985 song "Pine Tar Wars" to the event, composing a lyric that features an accurate[citation needed] telling of the relevant facts of the story. The lyric is strongly critical of Billy Martin, referring to him as "Tar Baby Billy".[31][32][33]

Left Field Brewery in Toronto, Ontario named one of its products the 'Pine Tar Incident IPA.' The craft brewery states that the India pale ale is a "dank, flavourful tribute to one of the game’s most controversial home run calls."[34]

See also[]

- Pine tar § Applications in baseball

References[]

- ^ Petri, Josh. "What Is Pine Tar And Why Is It Illegal In Baseball?". Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chass, Murray (July 25, 1983). "KC stuck with loss after pine tar homer". Lawrence Journal-World. (Kansas). New York Times News Service. p. 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jackson, Derrick (July 25, 1983). "Yankees stick it to Brett Royally on using an illegal bat". Pittsburgh Press. (Washington Post). p. C6.

- ^ "Brett's bat prompts battle Royal". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. July 25, 1983. p. 18.

- ^ "Too much tar nullifies homer". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. July 25, 1983. p. D3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c http://local.sandiego.com/sports/padres-manager-bud-black-relives-george-bretts-pine-tar-incident Archived August 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ruling by MacPhail yanks win from N.Y." Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. July 29, 1983. p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Brett says ruling courageous, but Yankees can't figure it out". Lawrence Journal-World. (Kansas). Associated Press. July 29, 1983. p. 15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Brett happy, umps angry". Pittsburgh Press. combined wire services. July 29, 1983. p. C2.

- ^ "Quisenberry saves tar victory; Yankees file one more protest". Lawrence Journal-World. (Kansas). Associated Press. August 19, 1983. p. 11.

- ^ "Pine tar nullifies home run, so Brett goes ballistic". Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Minnesota Twins 2, New York Yankees 1". Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ McKenzie, Mike (July 25, 1983). "Umpires' Ruling Beats the Tar Out of Royals". Kansas City Star. ISBN 9781582613376. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "The pine tar games from". The Hardball Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Yankees, Royals, courts put an end to Tar Wars". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 19, 1983. p. 13. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, Dick (August 22, 1983). "MacPhail's Folly". The Hour. Norwalk, Conn. p. 17.

After MacPhail ordered the Yanks and KC to play the last of the ninth inning, Lee and Bob Fishel and others in the league office held a meeting to discuss counter-strategy. They tried to anticipate what tricks the Yankees might come up with when they got on the field to play those last few outs. [...] And at that meeting it was Bob Fishel who suggested they should be ready in case the Yankees claimed Brett missed a base

- ^ "Judge blocks conclusion of KC-NY 'pine-tar' game". Daily Union. Junction City, Kansas. Associated Press. August 18, 1983. p. 9. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b van Dyck, Dave (August 20, 1983). "Final act of pine tar farce is panned by critics". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Infamous pine tar game over in 12 minutes". Merced Sun-Star. Associated Press. August 19, 1983. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "July 6, 1970 Washington Senators at Cleveland Indians Play by Play and Box Score". Baseball-Reference.com. July 6, 1970. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Preston, JG. "Left-handed throwing second basemen, shortstops and third basemen". prestonjg.wordpress.com. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler. (2008-07-24) Whatever Happened to Brett's Pine-Tar Bat? - NYTimes.com. Bats.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Schwartz, Ephraim. (2008-07-22) Can high tech really improve baseball? | Tech industry analysis. InfoWorld. Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Lidz, Franz. (1995-05-22) The Sultan Of Swap: From Babe Ruth's Spittoon To George Brett's Pine Tar, Barry Halper Has Begged, Bought And Bartered For A Fabulous Trove Of Baseball Treasures. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved on 2015-07-27.

- ^ Olson, Greg; Palmer, Ocean (2012). We Got to Play Baseball: 60 Stories from Men Who Played the Game. Strategic Book Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-61897-983-4.

- ^ Craig Peters (23 July 2006). "Who was the winning pitcher in the legendary pine tar game?". Athens Banner-Herald. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ Duquette, Dan (2012-05-07). "Kansas City Celebrates George Brett With Mini Pine Tar Bat Giveaway (Photo) | MLB". NESN.com. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ^ "The Royals are giving away a George Brett pine tar bobblehead, and yes, he looks intense". MLB.com. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ "2010 Official Baseball Rules" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ "The Pine-Tarred Bat (The Ballad of George Brett)". YouTube. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "Pine Tar Wars". YouTube. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ http://www.cw-mccall.com/works/passing_lane/pine_tar_wars.html

- ^ https://www.45cat.com/record/0018391

- ^ https://www.leftfieldbrewery.ca/beers/pine-tar-incident

Further reading[]

- Barbarisi, Daniel (July 8, 2013). "Pine Tar: The Untold Story". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 6, 2015. "The bat boy tells his version of the pine-tar tale involving George Brett and the Yankees." (subscription required)

- "Rose Colored Glasses". Snap Judgment. Segment: "The Bat Boy and the Pine Tar Game". Episode 625. October 2, 2015. Public Radio Exchange and NPR. Retrieved October 6, 2015. The radio version of the story, featuring an interview with the batboy, Merritt Riley.

- Bondy, Filip (2015). The Pine Tar Game: The Kansas City Royals, the New York Yankees, and Baseball's Most Absurd and Entertaining Controversy. Scribner. ISBN 978-1476777177.

- Carbone, Nick (September 25, 2012). "The Most Controversial Game Endings in Sports: The Pine Tar Incident". Time.

External links[]

- 1983 in sports in New York City

- 1983 Major League Baseball season

- Kansas City Royals

- Major League Baseball controversies

- Major League Baseball games

- New York Yankees

- Yankee Stadium (1923)

- July 1983 sports events in the United States