Polynesians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 2,000,000[1][need quotation to verify] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| New Zealand | 887,338 |

| United States | 820,000[2] |

| French Polynesia | c. 215,000 [3] |

| Australia | 210,843 |

| Samoa | 192,342 |

| Tonga | 103,036 |

| Cook Islands | 17,683 |

| Canada | 10,760[4] |

| Tuvalu | 10,645 [5] |

| Chile | 5,682 |

| Languages | |

| Polynesian languages (Hawaiian, Māori, Rapa Nui, Samoan, Tahitian, Tongan, Tuvaluan and others), English, French and Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (96.1%)[6] and Polynesian mythology[7] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Austronesians | |

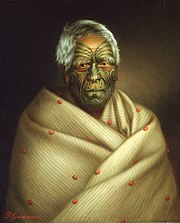

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Southeast Asia and form part of the larger Austronesian ethnolinguistic group with an Urheimat in Taiwan. They speak the Polynesian languages, a branch of the Oceanic subfamily of the Austronesian language family.

As of 2012 there were an estimated 2 million ethnic Polynesians (full and part) worldwide, the vast majority of whom either inhabit independent Polynesian nation-states (Samoa, Niue, Cook Islands, Tonga, and Tuvalu) or form minorities in countries such as Australia, Chile (Easter Island), New Zealand, France (French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna), United Kingdom Overseas Territories (Pitcairn Islands) and the United States (Hawaii and American Samoa). New Zealand had the highest population of Polynesians, estimated at 110,000 in 18th century.[8]

Polynesians have acquired a reputation as great navigators—their canoes reached the most remote corners of the Pacific, allowing the settlement of islands as far apart as Hawaii, Rapanui (Easter Island) and Aotearoa (New Zealand).[9] The people of Polynesia accomplished this voyaging using ancient navigation skills of reading stars, currents, clouds and bird movements—skills passed to successive generations down to the present day.[10]

Origins[]

Polynesians, including Samoans, Tongans, Niueans, Cook Islands Māori, Tahitian Mā'ohi, Hawaiian Māoli, Marquesans and New Zealandic Māori, are a subset of the Austronesian peoples. They share the same origins as the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, Southeast Asia (especially the Philippines, Malaysia and eastern Indonesia), Micronesia, and Madagascar.[11] This is supported by genetic,[12] linguistic[13] and archaeological evidence.

There are multiple hypotheses on the ultimate origin and mode of dispersal of the Austronesian peoples, but the most widely accepted theory is that modern Austronesians originated from migrations out of Taiwan between 3000 and 1000 BC. Using relatively advanced maritime innovations like the catamaran, outrigger boats, and crab claw sails, they rapidly colonized the islands of both the Indian and the Pacific oceans. They were the first humans to cross vast distances of water on ocean-going boats.[15][16] Polynesians are known to have definitely originated from a branch of the Austronesian migrations in Island Melanesia, despite the popularity of rejected hypotheses like Thor Heyerdahl's belief that Polynesians are descendants of "bearded white men" who sailed on primitive rafts from South America.[17][18]

The direct ancestors of the Polynesians were the Neolithic Lapita culture, which emerged in Island Melanesia and Micronesia at around 1500 BC from a convergence of migration waves of Austronesians originating from both Island Southeast Asia to the west and an earlier Austronesian migration to Micronesia to the north. The culture was distinguished by distinct dentate-stamped pottery. However, their eastward expansion stopped when they reached the western Polynesian islands of Fiji, Samoa and Tonga by around 900 BC. This remained the furthest extent of the Austronesian expansion in the Pacific for around 1,500 years, during which the Lapita culture in these islands abruptly lost the technology of making pottery for unknown reasons. They resumed their eastward migrations by around 700 AD, spreading to the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, and the Marquesas. From here, they spread further to Hawaii by 900 AD, Easter Island by 1000 AD, and finally New Zealand by 1200 AD.[19][20]

Genetic studies[]

Analysis by Kayser et al. (2008) discovered that only 21% of the Polynesian autosomal gene pool is of Australo-Melanesian origin, with the rest (79%) being of Austronesian origin.[21] Another study by Friedlaender et al. (2008) also confirmed that Polynesians are closer genetically to Micronesians, Taiwanese Aborigines, and Islander Southeast Asians, than to Papuans. The study concluded that Polynesians moved through Melanesia fairly rapidly, allowing only limited admixture between Austronesians and Papuans.[22] Polynesians belong almost entirely to the Haplogroup B (mtDNA) especially to mtDNA B4a1a1 (Polynesian motif), and thus the high frequencies of mtDNA B4 in the Polynesians are the result of drift and represent the descendants of a few Austronesian females who mixed with Papuan males.[23] The Polynesian population experienced a founder effect and genetic drift due to the ancestors of Polynesian being very few in numbers.[24][25] As a result of founder effect, the Polynesian are distinctively different both genotypically and phenotypically from the parent population from which it is derived. This is due to new population being established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population which also causes a loss of genetic variation.[26][27]

Soares et al. (2008) have argued for an older pre-Holocene Sundaland origin in Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) based on mitochondrial DNA.[28] The "out of Taiwan model" was challenged by a study from Leeds University and published in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Examination of mitochondrial DNA lineages shows that they have been evolving in ISEA for longer than previously believed. Ancestors of the Polynesians arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago of Papua New Guinea at least 6,000 to 8,000 years ago.[29]

A 2014 study by Lipson et al. using whole genome data supports the findings of Kayser et al. Modern Polynesians were shown to have lower levels of admixture with Australo-Melanesians than Austronesians in Island Melanesia. Regardless, both show admixture, along with other Austronesian populations outside of Taiwan, indicating varying degrees of intermarriage between the incoming Neolithic Austronesian settlers and the preexisting Paleolithic Australo-Melanesian populations of Island Southeast Asia and Melanesia.[30][31][32]

Other studies in 2016 and 2017 also support the implications that the earliest Lapita settlers mostly bypassed New Guinea, coming directly from Taiwan or the northern Philippines. The intermarriage and admixture with Australo-Melanesian Papuans evident in the genetics of modern Polynesians (as well as Islander Melanesians) occurred after the settlement of Tonga and Vanuatu.[33][34][35]

A 2020 study found that Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Polynesians came in contact around 1200.[36]

People[]

There are an estimated 2 million ethnic Polynesians and many of partial Polynesian descent worldwide, the majority of whom live in Polynesia, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.[1] The Polynesian peoples are shown below in their distinctive ethnic and cultural groupings (estimates of the larger groups are shown):

- Māori: New Zealand (Aotearoa) – c. 744,800[37] (not including 130,000 residing in Australia[38])

- Samoan: Samoa, American Samoa – c. 249,000 (worldwide: c. 500,000–600,000, including the 109,000 residing in the US and 145,000 in New Zealand)

- Tahitians (Maohi): Tahiti – c. 178,000 (including multiracial: 250,000+)

- Native Hawaiians: Hawaii – c. 140,000 (including multiracial: 400,000)

- Tongan: Tonga – c. 104,000 (+ 8,000 Australia, 35,000 U.S.A, & 60,300 New Zealand)

- Cook Islands Māori: Cook Islands – 98,000+ (including 62,000 in New Zealand and 16,000 residing in Australia)

- Niuean: Niue – c. 20,000–25,000 (95% of whom live in New Zealand)

- Tuvaluan: Tuvalu – c. 10,000 (+ 3,500 in New Zealand)

- Tokelauan: Tokelau – c. 1,500 (+ 6,500 in New Zealand)

- Tuamotu: Tuamotu Archipelago – c. 16,000

- Marquesas Islanders: Marquesas Islands – c. 11,000

- Rapanui: Easter Island – c. 5,000 (including mixtures and those living in Chile)

- Austral Islanders: Austral Islands – ~7,000

- Mangareva: Gambier Islands – c. 1,600

- Moriori: Chatham Islands (Rēkohu) – c. 738 (2013 New Zealand Census)

- Uvea and Futuna: Wallis and Futuna

- Kapingamarangi and Nukuoro: The Federated States of Micronesia

- Nuguria, Nukumanu and Takuu: Papua New Guinea

- Anuta, Bellona, Ontong Java, Rennel, Sikaiana, Tikopia and Vaeakau-Taumako: Solomon Islands

- Emae, Makata, Mele (Erakoro, Eratapu), Aniwa, and Futuna: Vanuatu

- Fagauvea: Ouvéa (New Caledonia)

See also[]

- History of the Polynesian people

- Polynesia

- Polynesian culture

- Polynesian languages

- Polynesian mythology

- Polynesian Society

- Polynesian American

- Pacific Islander

- Taiwanese Aborigines

- Micronesians

- Austronesian peoples

- Melanesians

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Pacific Islands & New Zealand".

- ^ Population Movement in the Pacific: A Perspective on Future Prospects. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Labour Archived 2013-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See page 80 in Landfalls of Paradise: Cruising Guide to the Pacific Islands, Earl R. Hinz & Jim Howard, University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Population of communities in Tuvalu". world-statistics.org. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Christianity in its Global Context, 1970–2020 Society, Religion, and Mission, Center for the Study of Global Christianity

- ^ Wellington, Victoria University of (1 December 2017). "Arts, humanities and social sciences". victoria.ac.nz. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. London: Penguin. p. 91.

- ^ Wilmshurst, Janet M.; Hunt, Terry L.; Lipo, Carl P.; Anderson, Atholl J. (2011-02-01). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (5): 1815–1820. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3033267. PMID 21187404.

- ^ DOUCLEFF, MICHAELEEN (23 January 2013). "How The Sweet Potato Crossed The Pacific Way Before The Europeans Did". NPR. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (2005). The Austronesians: historical and comparative perspectives. ISBN 9781920942854.

- ^ "Mitochondrial DNA Provides a Link between Polynesians and Indigenous Taiwanese". PLOS Biology. 3 (8): e281. 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030281. PMC 1166355.

- ^ "Pacific People Spread From Taiwan, Language Evolution Study Shows". ScienceDaily. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Chambers, Geoffrey K. (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (11 December 2008). "Austronesians were first to sail the seas". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Dr. Martin Richards. "Climate Change and Postglacial Human Dispersals in Southeast Asia". Oxford Journals. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Magelssen, Scott (March 2016). "White-Skinned Gods: Thor Heyerdahl, the Kon-Tiki Museum, and the Racial Theory of Polynesian Origins". TDR/The Drama Review. 60 (1): 25–49. doi:10.1162/DRAM_a_00522. S2CID 57559261.

- ^ Coughlin, Jenna (2016). "Trouble in Paradise: Revising Identity in Two Texts by Thor Heyerdahl". Scandinavian Studies. 88 (3): 246–269. doi:10.5406/scanstud.88.3.0246. JSTOR 10.5406/scanstud.88.3.0246. S2CID 164373747.

- ^ Heath, Helen; Summerhayes, Glenn R.; Hung, Hsiao-chun (2017). "Enter the Ceramic Matrix: Identifying the Nature of the Early Austronesian Settlement in the Cagayan Valley, Philippines". In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumara, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. 45. ANU Press. ISBN 9781760460952.

- ^ Carson, Mike T.; Hung, Hsiao-chun; Summerhayes, Glenn; Bellwood, Peter (January 2013). "The Pottery Trail From Southeast Asia to Remote Oceania". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 8 (1): 17–36. doi:10.1080/15564894.2012.726941. hdl:1885/72437. S2CID 128641903.

- ^ Kayser, Manfred; Lao, Oscar; Saar, Kathrin; Brauer, Silke; Wang, Xingyu; Nürnberg, Peter; Trent, Ronald J.; Stoneking, Mark (2008). "Genome-wide analysis indicates more Asian than Melanesian ancestry of Polynesians". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 194–198. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.010. PMC 2253960. PMID 18179899.

- ^ Friedlaender, Jonathan S.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Reed, Floyd A.; Kidd, Kenneth K.; Kidd, Judith R.; Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Lea, Rodney A.; et al. (2008). "The genetic structure of Pacific Islanders". PLOS Genetics. 4 (1): e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. PMC 2211537. PMID 18208337.

- ^ Assessing Y-chromosome Variation in the South Pacific Using Newly Detected, By Krista Erin Latham

- ^ Murray-McIntosh, Rosalind P.; Scrimshaw, Brian J.; Hatfield, Peter J.; Penny, David (21 July 1998). "Testing migration patterns and estimating founding population size in Polynesia by using human mtDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (15): 9047–9052. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9047M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9047. PMC 21200. PMID 9671802.

- ^ Kallen, Evelyn (1982-01-01). The Western Samoan Kinship Bridge: A Study in Migration, Social Change, and the New Ethnicity. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-9004065420.

- ^ Provine, W. B. (2004). "Ernst Mayr: Genetics and speciation". Genetics. 167 (3): 1041–6. doi:10.1093/genetics/167.3.1041. PMC 1470966. PMID 15280221.

- ^ Templeton, A. R. (1980). "The theory of speciation via the founder principle". Genetics. 94 (4): 1011–38. doi:10.1093/genetics/94.4.1011. PMC 1214177. PMID 6777243.

- ^ Martin Richards. "Climate Change and Postglacial Human Dispersals in Southeast Asia". Oxford Journals. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ DNA Sheds New Light on Polynesian Migration, by Sindya N. Bhanoo, Feb. 7, 2011, The New York Times

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Loh, Po-Ru; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Ko, Ying-Chin; Stoneking, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David (2014). "Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4689. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4689L. doi:10.1038/ncomms5689. PMC 4143916. PMID 25137359.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Loh, Po-Ru; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Ko, Ying-Chin; Stoneking, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David (19 August 2014). "Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4689. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4689L. doi:10.1038/ncomms5689. PMC 4143916. PMID 25137359.

- ^ Kayser, Manfred; Brauer, Silke; Cordaux, Richard; Casto, Amanda; Lao, Oscar; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Moyse-Faurie, Claire; Rutledge, Robb B.; Schiefenhoevel, Wulf; Gil, David; Lin, Alice A.; Underhill, Peter A.; Oefner, Peter J.; Trent, Ronald J.; Stoneking, Mark (November 2006). "Melanesian and Asian Origins of Polynesians: mtDNA and Y Chromosome Gradients Across the Pacific". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (11): 2234–2244. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl093. PMID 16923821.

- ^ Pontus Skoglund; et al. (27 October 2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418.

- ^ Skoglund, Pontus; Posth, Cosimo; Sirak, Kendra; Spriggs, Matthew; Valentin, Frederique; Bedford, Stuart; Clark, Geoffrey R.; Reepmeyer, Christian; Petchey, Fiona; Fernandes, Daniel; Fu, Qiaomei; Harney, Eadaoin; Lipson, Mark; Mallick, Swapan; Novak, Mario; Rohland, Nadin; Stewardson, Kristin; Abdullah, Syafiq; Cox, Murray P.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Friedlaender, Jonathan S.; Kivisild, Toomas; Koki, George; Kusuma, Pradiptajati; Merriwether, D. Andrew; Ricaut, Francois-X.; Wee, Joseph T. S.; Patterson, Nick; Krause, Johannes; Pinhasi, Ron; Reich, David (3 October 2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418.

- ^ "First ancestry of Ni-Vanuatu is Asian: New DNA Discoveries recently published". Island Business. December 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "DNA reveals Native American presence in Polynesia centuries before Europeans arrived".

- ^ "Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2018 | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ "One in six Māori now living in Australia, research shows". Stuff. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

External links[]

Media related to People of Polynesia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to People of Polynesia at Wikimedia Commons

- Ethnic groups in Oceania

- Polynesian people

- Indigenous peoples of Polynesia

- Ethnic groups in New Zealand

- Ethnic groups in the United States

- Ethnic groups in Australia

- Polynesian Australian

- Polynesian New Zealander

- Austronesian peoples