Porto-Novo

Porto-Novo

Xɔ̀gbónù Hogbonu, Àjàshé Ilé | |

|---|---|

City and commune | |

Photos of Porto-Novo | |

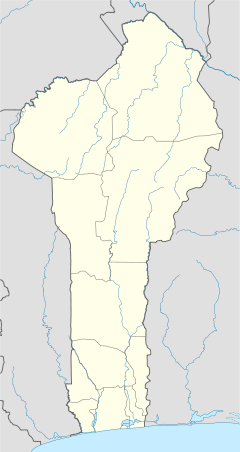

Porto-Novo Location of Porto-Novo in Benin | |

| Coordinates: 6°29′50″N 2°36′18″E / 6.49722°N 2.60500°ECoordinates: 6°29′50″N 2°36′18″E / 6.49722°N 2.60500°E | |

| Country | |

| Department | Ouémé |

| Established | 16th century |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Emmanuel Zossou |

| Area | |

| • City and commune | 110 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 110 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 38 m (125 ft) |

| Population (2013)[1] | |

| • City and commune | 264,320 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,200/sq mi) |

| Website | Official website |

Porto-Novo (French pronunciation: [pɔʁtɔnɔvo]; also known as Hogbonu and Ajashe; Fon: Xɔ̀gbónù) is the capital of Benin. The commune covers an area of 110 square kilometres (42 sq mi) and as of 2002 had a population of 223,552 people.[2][3]

As the name suggests, Porto-Novo (Portuguese: "New Port", Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpoɾtu ˈnovu]) was originally developed as a port for the transatlantic slave trade led by the Portuguese Empire.

Porto-Novo is a port on an inlet of the Gulf of Guinea, in the southeastern portion of the country. It is Benin's second-largest city, and although Porto-Novo is the official capital, where the national legislature sits, the larger city of Cotonou is the seat of government, where most of the government buildings are situated and government departments operate.

Etymology[]

The name Porto-Novo is of Portuguese origin, literally meaning "New Port". It remains untranslated in French, the national language of Benin.

History[]

Porto-Novo was once a tributary of the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo,[4][5] which had offered it protection from the neighbouring Fon, who were expanding their influence and power in the region. The Yoruba community in Porto-Novo today remains one of the two ethnicities aboriginal to the city. The city was originally called Ajashe by the Yorubas, and Hogbonu by the Gun.[citation needed]

Although historically the original inhabitants of the area were Yoruba speaking, there seems to have been a wave of migration from the region of Allada further west in the 1600s, which brought Te-Agbalin (or Te Agdanlin) and his group to the region of Ajashe in 1688.[6] This new group brought with them their own language, and settled among the original Yoruba. It would appear that each ethnic group has since maintained their ethnic idenitites without one group being linguistically assimilated into the other.[citation needed]

In 1730, the Portuguese Eucaristo de Campos named the city "Porto-Novo" because of its resemblance to the city of Porto.[7][8] It was originally developed as a port for the slave trade.[9]

In 1861, the British, who were active in nearby Nigeria, bombarded the city, which persuaded the Kingdom of Porto-Novo to accept French protection in 1863.[10] The neighbouring Kingdom of Dahomey objected to French involvement in the region and war broke out between the two states. In 1883, Porto-Novo was incorporated into the French "colony of Dahomey and its dependencies" and in 1900, it became Dahomey's capital city.[6] As a consequence, a community that had previously exhibited endoglossic bilingualism now began to exhibit exoglossic bilingualism, with the addition of French to the language repertoire of the city's inhabitants.[citation needed] Unlike the city's earlier Gun migrants, however, the French sought to impose their language in all spheres of life and completely stamp out the use and proliferation of indigenous languages.[citation needed]

The kings of Porto-Novo continued to rule in the city, both officially and unofficially, until the death of the last king, , in 1976.[6] From 1908, the king held the title of Chef supérieur.[citation needed]

Many Afro-Brazilians settled in Porto-Novo following their return to Africa after emancipation in Brazil.[citation needed] Brazilian architecture and foods are important to the city's cultural life.[citation needed]

Under French colonial rule, flight across the new border to British-ruled Nigeria in order to avoid harsh taxation, military service and forced labour was common.[citation needed] Of note is the fact that the Nigeria-Benin southern border area arbitrarily cuts through contiguous areas of Yoruba and Egun-speaking people. A combination of the aforementioned facts, coupled with the fact that the city itself lies within the sphere of Nigerian socioeconomic influence, have given Porto-Novians a preference for some measure of bi-nationality or dual citizenship, with the necessary linguistic consequences; for example, Nigerian home video films in Yoruba with English subtitles have become popular in Porto-Novo and its suburbs.[citation needed]

Seat of government[]

Benin's parliament (Assemblée nationale) is in Porto-Novo, the official capital, but Cotonou is the seat of government and houses most of the governmental ministries.

Economy[]

The region around Porto-Novo produces palm oil, cotton and kapok.[citation needed] Petroleum was discovered off the coast of the city in the 1990s, and has since then become an important export.[citation needed] Porto-Novo has a cement factory.[citation needed] The city is home to a branch of the Banque Internationale du Bénin, a major bank in Benin, and the .[citation needed]

Transport[]

Porto-Novo is served by an extension of the Bénirail train system.[citation needed] Privately owned motorcycle taxis known as zemijan are used throughout the city.[11] The city is located about 40 kilometres (25 miles) away from Cotonou Airport, which has flights to major cities in West Africa and Europe.

Demographics[]

Porto-Novo had an enumerated population of 264,320 in 2013.[1] The residents are mostly Yoruba and Gun people as well as people from other parts of the country, and from neighbouring Nigeria.

Population trend:[1]

- 1979: 133,168 (census)

- 1992: 179,138 (census)

- 2002: 223,552 (census)

- 2013: 264,320 (census)

Geography and climate[]

Porto-Novo has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) with consistently hot and humid conditions and two wet seasons: a long wet season from March to July and a shorter rain season in September and October. The city’s location on the edge of the Dahomey Gap makes it much drier than would be expected so close to the equator, although it is less dry than Accra or Lomé.

| hideClimate data for Porto-Novo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 23 (0.9) |

34 (1.3) |

86 (3.4) |

127 (5.0) |

215 (8.5) |

370 (14.6) |

129 (5.1) |

44 (1.7) |

89 (3.5) |

140 (5.5) |

52 (2.0) |

16 (0.6) |

1,325 (52.1) |

| Source: [12] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions[]

Culture[]

- The Porto-Novo Museum of Ethnography contains a large collection of Yoruba masks, as well as items on the history of the city and of Benin.[6]

- King Toffa's Palace (also known as the Musée Honmé and the Royal Palace), now a museum, shows what life was like for African royalty.[6] The palace and the surrounding district was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on October 31, 1996 in the Cultural category.[13]

- Jardin Place Jean Bayol is a large plaza which contains a statue of the first King of Porto-Novo.

- The Da Silva Museum is a museum of Beninese history.[6] It shows what life was like for the returning Afro-Brazilians.

- The palais de Gouverneur (governor's palace) is the home of the national legislature.

- The Isèbayé Foundation is a museum of Voodoo and Beninese history.[6]

Music[]

music is endemic to Porto-Novo.[14] The style of music is played on an alounloun, a stick with metallic rings attached which jingle in time with the beating of the stick.[citation needed] The alounloun is said to descend from the staff of office of King Te-Agdanlin and was traditionally played to honour the King and his ministers.[citation needed] The music is also played in the city's Roman Catholic churches, but the royal bird crest symbol has been replaced with a cross.[citation needed]

Sports[]

The Stade Municipale and the Stade Charles de Gaulle are the largest football stadiums in the city.[citation needed]

Places of worship[]

Among the places of worship, Christian churches are predominant: Roman Catholic Diocese of Porto Novo (Catholic Church), Protestant Methodist Church in Benin (World Methodist Council), Celestial Church of Christ, (Baptist World Alliance), Living Faith Church Worldwide, Redeemed Christian Church of God, Assemblies of God.[15] There are also Muslim mosques, most notably the Grand Mosque.[6] There are also several Voodoo temples in the city.[6]

Notable people[]

- Alexis Adandé, archaeologist[16]

- Anicet Adjamossi, footballer.[17]

- Kamarou Fassassi, politician.[18]

- Romuald Hazoume, artist[19]

- Samuel Oshoffa, who founded the Celestial Church of Christ.[20]

- Marc Tovalou Quenum, lawyer, writer and pan-africanist.[21]

- Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, director and author[22]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Benin: Departments, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information".

- ^ "Porto-Novo". Atlas Monographique des Communes du Benin. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Communes of Benin". Statoids. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Erica Kraus; Felicie Reid (2010). Benin (Other Places Travel Guide). Other Places Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-982-2619-10. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Mathurin C. Houngnikpo; Samuel Decalo (2013). Historical Dictionary of Benin (African Historical Dictionaries). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-81087-17-17. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Butler, Stuart (2019) Bradt Travel Guide - Benin, pgs. 121-131

- ^ Mathurin C. Houngnikpo, Samuel Decalo, Historical Dictionary of Benin, Rowman & Littlefield, USA, 2013, p. 297

- ^ Britannica, Porto-Novo, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- ^ Fiona McLaughlin (2011). Languages of Urban West Africa. ISBN 978-1-4411-5-81-30. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Hargreaves, John (1963). Prelude to the Partition of West Africa. London: MacMilland. pp. 59–60.[ISBN missing]

- ^ ZEMIJAN - Taxis motos (Bénin, ancien Dahomey), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-nzWaCHRiE

- ^ "Weatherbase". Weatherbase. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ La ville de Porto-Novo : quartiers anciens et Palais Royal - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ^ Adjogan in Porto-Novo (Hogbonou) - Archives (Benin, ex-Dahomey), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OEWznXa7mwo

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 338

- ^ N’Dah, Didier (2014), "Adandé, Alexis B. A.", in Smith, Claire (ed.), Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Springer, pp. 20–22, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_2359, ISBN 978-1-4419-0465-2

- ^ Adjamossi profile, (in French)

- ^ "Government page on Fassassi" (in French). Archived from the original on November 19, 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-07.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link).

- ^ Romuald Hazoumè October Gallery Co., retrieved 4 Apr 2020

- ^ Crumbly, Deidre Helen (2008). Spirit, Structure, and Flesh: Gendered Experiences in African Instituted Churches Among the Yoruba of Nigeria. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-299-22910-8.

- ^ Marc Tovalou Quenum profile, (in English)

- ^ Paulin Soumanou Vieyra African Film NY.org, retrieved 4 Apr 2020

Further reading[]

- Sappho Charney (1996). "Porto-Novo (Oueme, Benin)". In Noelle Watson (ed.). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. UK: Routledge. p. 588+. ISBN 1884964036.

External links[]

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Porto-Novo. |

- Porto-Novo

- Capitals in Africa

- Communes of Benin

- French West Africa

- Populated coastal places in Benin

- Populated places in the Ouémé Department

- Cities in Yorubaland

- Populated places established in the 16th century