Portuguese man o' war

| Portuguese man o' war | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Siphonophorae |

| Suborder: | Cystonectae |

| Family: | Physaliidae Brandt, 1835[2] |

| Genus: | Physalia Lamarck, 1801[1] |

| Species: | P. physalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Physalia physalis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

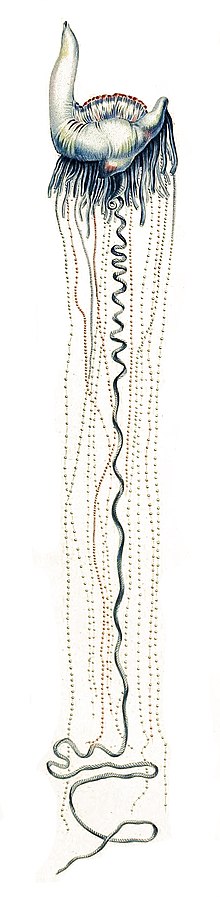

The Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis), also known as the man-of-war,[6] bluebottle, or blue bottle jellyfish,[7] is a marine hydrozoan found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean. It is considered to be the same species as the Pacific man o' war, which is found mainly in the Pacific Ocean. The Portuguese man o' war is the only species in the genus Physalia, which in turn is the only genus in the family Physaliidae.[8]

The Portuguese man of war is a conspicuous member of the neuston, the community of organisms that live at the ocean surface. It has numerous venomous microscopic nematocysts which deliver a painful sting powerful enough to kill fish, and has been known to occasionally kill humans. Although it superficially resembles a jellyfish, the Portuguese man o' war is in fact a siphonophore. Like all siphonophores, it is a colonial organism, made up of many smaller units called zooids.[9] All zooids in a colony are genetically identical, but fulfill specialized functions such as feeding and reproduction, and together allow the colony to operate as a single individual.

Etymology[]

The name man o' war comes from the man-of-war, an 18th-century sailing warship,[10] and the animal's resemblance to the Portuguese version (the caravel) at full sail.[11][5][6]

Overview[]

The Portuguese man of war is one of the most conspicuous, but poorly understood members of the neuston, a community of organisms that occupy a habitat at the sea-air interface. Physalia physalis is a siphonophore that uses a gas-filled float as a sail to catch the wind.[9] The neuston is the floating community of ocean organisms that live at the interface between water and air. This community is exposed to a unique set of environmental conditions including prolonged exposure to intense ultraviolet light, desiccation risk, and rough sea and wave conditions.[12] Despite their tolerance for extreme environmental conditions and the very large size of this habitat, which makes up 71% of the Earth’s surface and is nearly three times the area of all terrestrial habitats, very little is known about the organisms that make up this highly specialized polyphyletic community. One of the most conspicuous, yet poorly understood, members of the neuston is the siphonophore Physalia physalis, commonly known as the Portuguese man of war. The Portuguese man of war is aptly named after a warship: it uses part of an enlarged float filled with carbon monoxide and air as a sail to travel by wind for thousands of miles, dragging behind long tentacles that deliver a deadly venomous sting to fish.[13][14] This sailing ability, combined with a painful sting and a life cycle with seasonal blooms, results in periodic mass beach strandings and occasional human envenomations, making P. physalis the most infamous siphonophore.[15][9]

The development, morphology, and colony organization of P. physalis is very different from all other siphonophores. [9] Siphonophores are a relatively understudied group of colonial hydrozoans. Colonies are composed of functionally specialized bodies (termed zooids) that are homologous to free living individuals. Most species are planktonic and are found at most depths from the deep sea to the surface of the ocean.[16][17][18] They are fragile and difficult to collect intact, and must be collected by submersible, remotely operated vehicle, by hand while blue-water diving, or in regions with localized upwellings.[19][20] However, Physalia physalis is the most accessible, conspicuous, and robust siphonophore, and as such, much has been written about this species, including the chemical composition of its float, venom (especially envenomations), occurrence, and distribution.[15][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] Fewer studies, however, have taken a detailed look at P. physalis structure, including development, histology of major zooids, and broader descriptions of colony arrangement.[32][33][34][35] These studies provide an important foundation for understanding the morphology, cellular anatomy, and development of this neustonis species. It can be difficult to understand the morphology, growth, and development of P. physalis within the context of siphonophore diversity, as the colony consists of highly 3-dimensional branching structures and develops very different from all other siphonophores.[9]

The bluebottle resembles a jellyfish but is actually a siphonophore, a colonial organism composed of small individual animals called zooids.[36] There are four zooids depending on each other for survival and performing different functions, such as digestion (gastrozooids), reproduction (gonozooids) and hunting (dactylozooids). The last zooid, the pneumatophore, is a gas-filled float or sac that supports the other zooids and acts like a sail so the bluebottle is constrained to the ocean surface, moving at the mercy of the wind, waves and marine currents. The bluebottle's long tentacles hang below the float as they drift, fishing for prey to sting and drag up to their digestive zooids.[36][37]

The Indo-Pacific Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis) or the bluebottle (Physalia utriculus, a synonym), is well known on the coasts of Japan, Indonesia as well as the east coast of Australia for stinging tens of thousands of beachgoers each year.[38] The species is found throughout the world's oceans, in tropical, subtropical and (occasionally) temperate regions.[9][37]

Anatomy and physiology[]

Anatomy of a Physalia physalis colony [9]

with descriptions of the function of each zooid

Just like all siphonophores, the Portuguese man o' war is colonial: each man o' war is composed of many smaller units (zooids) that hang in clusters from under a large, gas-filled structure called the pneumatophore.[39] New zooids are added by budding as the colony grows. As many as seven different kinds of zooids have been described in the man o' war: three of the medusoid type (gonophores, nectophores, and vestigial nectophores) and four of the polypoid type (free gastrozooids, tentacle-bearing zooids, gonozooids and gonopalpons).[40] However, naming and categorization of zooids varies between authors, and much of the embryonic and evolutionary relationships of zooids remains unclear.[9]

The pneumatophore, or bladder, is the most conspicuous part of the man o' war. It is translucent and tinged blue, purple, pink, or mauve, and may be 9 to 30 centimetres (3+1⁄2 to 12 inches) long and rise as high as 15 cm (6 in) above the water. The pneumatophore functions as both a flotation device and a sail for the colony, allowing the colony to move with the prevailing wind.[9][39] The gas in the pneumatophore is part carbon monoxide (0.5–13%), which is actively produced by the animal, and part atmospheric gases (nitrogen, oxygen and noble gases) that diffuse in from the surrounding air.[41] In the event of a surface attack, the pneumatophore can be deflated, allowing the colony to temporarily submerge.[42]

The colony hunts and feeds through the cooperation of two types of zooid: gastrozooids and tentacle-bearing zooids known as dactylozooids[9] or tentacular palpons. The dactylozooids are equipped with tentacles, which are typically about 10 m (30 ft) in length but can reach over 30 m (100 ft).[43][44] Each tentacle bears tiny, coiled, thread-like structures called nematocysts. Nematocysts trigger and inject venom on contact, stinging, paralyzing, and killing adult or larval squids and fishes. Large groups of Portuguese man o' war, sometimes over 1,000 individuals, may deplete fisheries.[40][42] Contraction of tentacles drags the prey upward, into range of the gastrozooids, the digestive zooids. The gastrozooids surround and digest the food by secreting enzymes.

The main reproductive zooids, the gonophores, are situated on branching structures called gonodendra. Gonophores produce sperm or eggs (see life cycle). Besides gonophores, each gonodendron also contains several other types of specialized zooids: gonozooids (which are accessory gastrozooids), nectophores (which have been speculated to allow detached gonodendra to swim), and vestigial nectophores (also called jelly polyps; the function of these is unclear).[9]

Colonial[]

The man o' war is described as a colonial organism because the individual zooids in a colony are evolutionarily derived from either polyps or medusae,[45] i.e. the two basic body plans of cnidarians.[46] Both of these body plans comprise entire individuals in non-colonial cnidarians (for example, a jellyfish is a medusa; a sea anemone is a polyp). All zooids in a man o' war develop from the same single fertilized egg and are therefore genetically identical; they remain physiologically connected throughout life, and essentially function as organs in a shared body. Hence, a Portuguese man o' war constitutes a single individual from an ecological perspective, but is made up of many individuals from an embryological perspective.[45]

Distribution[]

Portuguese man o' war washed up on a beach

They are often found ashore in large groups

Found mostly in tropical and subtropical waters,[47][48] the Portuguese man-o-war lives at the surface of the ocean. The gas-filled bladder, or pneumatophore, remains at the surface, while the remainder is submerged.[49] Portuguese man-o-war have no means of propulsion, and move passively, driven by the winds, currents, and tides.

Winds can drive them into bays or onto beaches. Often, finding a single Portuguese man o' war is followed by finding many others in the vicinity.[43] The Portuguese man o' war is well known to beachgoers for the painful stings delivered by its tentacles.[37] Because they can sting while beached, the discovery of a man o' war washed up on a beach may lead to the closure of the beach.[50][51]

Drifting dynamics[]

Looking down from above a man o' war, showing its sail. Sails can be left-handed or right-handed.

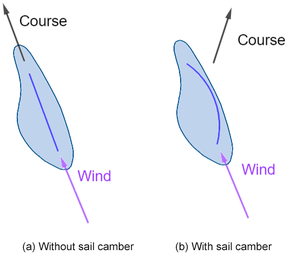

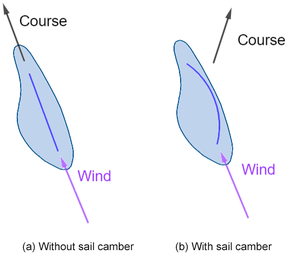

The bluebottle course at zero angle of attack is dependent on the sail camber [37]

Despite being a common occurrence, the origin of the man 'o war or bluebottle before reaching the coastline is not well understood, and neither is the way it drifts at the surface of the ocean.[37]

Left- and right-handed[]

For each man 'o war or bluebottle, the float can be oriented towards the left or the right (dimorphism), believed to be an adaptation that prevents the entire population from being washed on shore to die.[52][53] The "left-handed" bluebottles sail to the right of the wind, while the "right-handed" bluebottles sail to the left. The wind will always push the two types of bluebottles in different directions, so at most half the population will be pushed towards the coast.[52][53] The Atlantic Portuguese man o' war (PMW) is considered the same species as the bluebottle, but with key differences in their size and the number of long tentacles used for hunting. The bluebottle's float rarely exceeds 10 cm and it has one long hunting tentacle that is less than 3 m in length. In comparison, the PMW has floats of around 15 cm, reported up to 30 cm, and several hunting tentacles that can reach 30 m in mature colonies when fully extended.[9][37]

A Portuguese man o' war is somewhat asymmetrically shaped: the zooids of the colony hang down not quite from the midline of the pneumatophore, but offset to either the right or left side of the midline. When combined with the trailing action of the tentacles (which function as a sea anchor), this left- or right-handedness makes the colony sail sideways relative to the wind, by about 45° in either direction.[54][55] Colony handedness has therefore been theorized to affect man o' war migration, with left-handed or right-handed colonies potentially being more likely to drift down particular respective sea routes.[54] While previously believed to develop as a result of what winds a colony experienced, handedness in fact emerges early in the colony's life, while it is still living below the surface of the sea.[9]

Mathematical modelling[]

Due to their inability to swim, the movement of the man 'o war or bluebottle can be modelled mathematically by calculating the forces acting on it, or by advecting virtual particles in ocean and atmospheric circulation models. Earlier studies modelled the movement of the man 'o war with Lagrangian particle tracking to explain major beaching events. In 2017, Ferrer and Pastor were able to estimate the region of origin of a significant beaching event on the Basque coast.[56] They ran a Lagrangian model backwards in time, using wind velocity and a wind drag coefficient as drivers of the man 'o war motion. They found that the region of origin was the North Atlantic subtropical gyre.[56] In 2015 Prieto et al. included both the effect of the surface currents and wind to predict the initial colony position prior to major beaching events in the Mediterranean.[57] This model assumed the man 'o war was advected by the surface currents, with the effect of the wind being added with a much higher wind drag coefficient of 10 percent. Similarly, in 2020 Headlam et al. used beaching and offshore observations to identify a region of origin, using the joint effects of surface currents and wind drag, for the largest mass man 'o war beaching on the Irish coastline in over 150 years.[58][37] These earlier studies used numerical models in combination with simple assumptions to calculate the drift of this species, excluding complex drifting dynamics. In 2021, Lee et al. provide a parameterisation for Lagrangian modelling of the bluebottle by considering the similarities between the bluebottle and a sailboat. This allowed them to compute the hydrodynamic and aerodynamic forces acting on the bluebottle and use an equilibrium condition to create a generalised model for calculating the drifting speed and course of the bluebottle under any wind and ocean current conditions.[37]

Ecology[]

Predators and prey[]

Blue dragon, glaucus atlanticus

Violet snail, Janthina janthina

The Portuguese man o' war is a carnivore.[43] Using its venomous tentacles, a man o' war traps and paralyzes its prey while "reeling" it inwards to the digestive polyps. It typically feeds on small marine organisms, such as fish and plankton and sometimes shrimp.

The organism has few predators of its own; one example is the loggerhead turtle, which feeds on the Portuguese man o' war as a common part of its diet.[59] The turtle's skin, including that of its tongue and throat, is too thick for the stings to penetrate. Also, the blue sea slug Glaucus atlanticus specializes in feeding on the Portuguese man o' war,[60] as does the violet snail Janthina janthina.[61] The ocean sunfish's diet, once thought to consist mainly of jellyfish, has been found to include many species, the Portuguese man o' war being one such example.[62][63]

The blanket octopus is immune to the venom of the Portuguese man o' war; young individuals have been observed to carry broken man o' war tentacles,[64] which males and immature females rip off and use for offensive and defensive purposes.[65]

| External video | |

|---|---|

– Blue Planet II |

The man-of-war fish, Nomeus gronovii, is a driftfish native to the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. It is notable for its ability to live within the deadly tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war, upon whose tentacles and gonads it feeds. Rather than using mucus to prevent nematocysts from firing, as is seen in some of the clownfish sheltering among sea anemones, the fish appears to use highly agile swimming to physically avoid tentacles.[66][67] The fish has a very high number of vertebrae (41), which may add to its agility[67] and primarily uses its pectoral fins for swimming—a feature of fish that specialize in maneuvering tight spaces. It also has a complex skin design and at least one antigen to the man o' war's toxin.[67] Although the fish seems to be 10 times more resistant to the toxin than other fish, it can be stung by the dactylozooides (large tentacles), which it actively avoids.[66] The smaller gonozooids do not seem to sting the fish and the fish is reported to frequently "nibble" on these tentacles.[66]

Commensalism and symbiosis[]

The Portuguese man o' war is often found with a variety of other marine fish, including yellow jack. These fish benefit from the shelter from predators provided by the stinging tentacles, and for the Portuguese man o' war, the presence of these species may attract other fish to eat.[68]

Life cycle[]

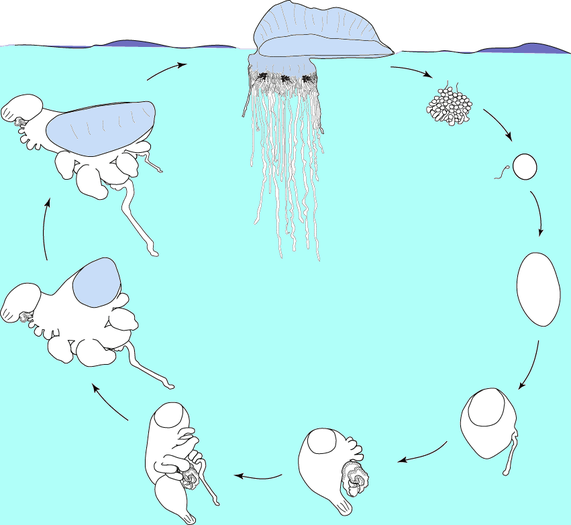

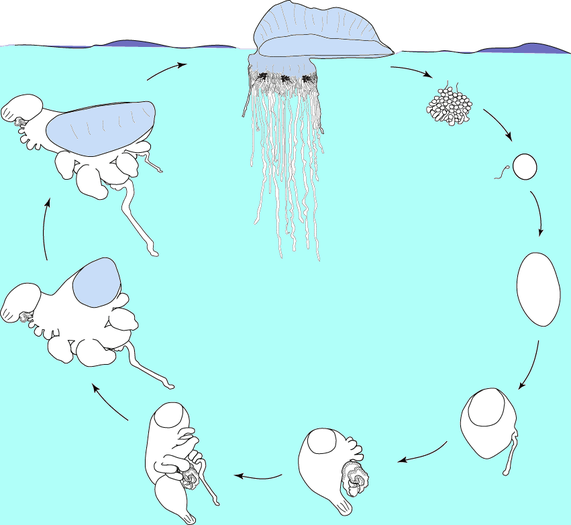

Lifecycle of the Portuguese man of war [9]

The mature Physalia physalis is pictured floating on the ocean surface, while early development is thought to occur at an unknown depth below the ocean surface. The gonodendra are thought to be released from the colony when mature. The egg and planula larva stage have not been observed.

Man o' war individuals are dioecious, meaning each colony is either male or female.[39][9] Gonophores producing either sperm or eggs (depending on the sex of the colony) sit on a tree-like structure called a gonodendron, which is believed to drop off from the colony during reproduction.[9] Mating takes place primarily in the autumn, when eggs and sperm are shed from gonophores into the water.[39] As neither fertilization nor early development have been directly observed in the wild, it is not yet known at what depth they occur.[9]

A fertilized man o' war egg develops into a larva that buds off new zooids as it grows, gradually forming a new colony. This development initially occurs under the water, and has been reconstructed by comparing different stages of larvae collected at sea.[9] The first two structures to emerge are the pneumatophore (sail) and a single, early feeding zooid called a protozooid; later, gastrozooids and tentacle-bearing zooids are added. Eventually, the growing pneumatophore becomes buoyant enough to carry the immature colony on the surface of the water.[9]

Venom[]

The stinging, venom-filled nematocysts in the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war can paralyze small fish and other prey.[69] Detached tentacles and dead specimens (including those that wash up on shore) can sting just as painfully as the live organism in the water, and may remain potent for hours or even days after the death of the organism or the detachment of the tentacle.[70]

Stings usually cause severe pain to humans, leaving whip-like, red welts on the skin that normally last two or three days after the initial sting, though the pain should subside after about 1 to 3 hours (depending on the biology of the person stung). However, the venom can travel to the lymph nodes and may cause symptoms that mimic an allergic reaction, including swelling of the larynx, airway blockage, cardiac distress, and an inability to breathe. Other symptoms can include fever and shock, and in some extreme cases, even death,[71] although this is extremely rare. Medical attention for those exposed to large numbers of tentacles may become necessary to relieve pain or open airways if the pain becomes excruciating or lasts for more than three hours, or if breathing becomes difficult. Instances where the stings completely surround the trunk of a young child are among those that have the potential to be fatal.[72]

The species is responsible for up to 10,000 human stings in Australia each summer, particularly on the east coast, with some others occurring off the coast of South Australia and Western Australia.[73]

Treatment of stings[]

Stings from a Portuguese man o' war can result in severe dermatitis characterized by long, thin, open wounds that resemble those caused by a whip.[74] These are not caused by any impact or cutting action, but by irritating urticariogenic substances in the tentacles.[75][76] Flushing the affected area with sea water helps remove any adherent tentacles in the wound area.[72][77][78][79]

Acetic acid (vinegar) can deactivate the remaining nematocysts and usually provides some pain relief,[72] though some isolated studies suggest that in some individuals vinegar dousing may increase toxin delivery and worsen symptoms.[77][80] Vinegar has also been claimed to provoke hemorrhaging when used on the less severe stings of cnidocytes of smaller species.[81].

However, a 2017 study found a wash of undiluted vinegar or Sting No More Spray, a proprietary "combined stinging capsule and venom-inhibiting product" were the most effective topical rinse solutions.[82] The vinegar (or spray) rinse should be followed by immersion in 45°C (113°F) water or application of a hot pack for 45 minutes.[82][83]

Gallery[]

Man o' war warning sign at Hawaii

Portuguese man o' war

See also[]

- Chondrophores (porpitids), a different hydrozoan colonial organism

- Velella, a smaller hydrozoa which has a similar shape and colouration.[84]

- Porpita porpita

- Siphonophorae

References[]

- ^ Lamarck, J. B. (1801). Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux; Présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'apres la considération de leurs rapports naturels et de leur organisation, et suivant l'arrangement établi dans les galeries du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle, parmi leurs dépouilles conservées; Précédé du discours d'ouverture du Cours de Zoologie, donné dans le Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle l'an 8 de la République (Thesis). Published by the author and Deterville, Paris: pp. viii + 432. p. 355. Archived from the original on 2017-05-27.

- ^ Brandt, Johann Friedrich (1834–1835). "Prodromus descriptionis animalium ab H. Mertensio in orbis terrarum circumnavigatione observatorum. Fascic. I., Polypos, Acalephas Discophoras et Siphonophoras, nec non Echinodermata continens". Recueil Actes des séances publiques de l'Acadadémie impériale des Science de St. Pétersbourg 1834: 201–275. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01.CS1 maint: date format (link) page(s): 236

- ^ Schuchert, P. (2019). "World Hydrozoa Database. Physaliidae Brandt, 1835". World Register of Marine Species. Archived from the original on 2018-10-27. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- ^ Schuchert, P. (2019). World Hydrozoa Database. Physalia Lamarck, 1801. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135382 Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine on 2019-03-11

- ^ a b Schuchert, P. (2019). World Hydrozoa Database. Physalia physalis (Linnaeus, 1758). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135479 Archived 2018-07-27 at the Wayback Machine on 2019-03-11

- ^ a b "Portuguese man-of-war". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Blue bottle jellyfish back on Mumbai's Juhu beach, experts warn visitors to avoid contact". The Indian Express. 2021-08-03. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Physalia Lamarck, 1801". www.marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Munro, Catriona; Vue, Zer; Behringer, Richard R.; Dunn, Casey W. (2019-10-29). "Morphology and development of the Portuguese man of war, Physalia physalis". Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 9 (1): 15522. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915522M. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51842-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6820529. PMID 31664071.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Greene, Thomas F. Marine Science Textbook.

- ^ Millward, David (8 September 2012). "Surge in number of men o'war being washed up on beaches". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Zaitsev Y, Liss P (1997). "Neuston of seas and oceans". In Duce R (ed.). The sea surface and global change. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01745-9. OCLC 847978750.

- ^ Clark, F. E.; Lane, C. E. (1961). "Composition of Float Gases of Physalia physalis". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 107 (3): 673–674. doi:10.3181/00379727-107-26724. PMID 13693830. S2CID 2687386.

- ^ Iosilevskii, G.; Weihs, D. (2009). "Hydrodynamics of sailing of the Portuguese man-of-war Physalia physalis". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 6 (36): 613–626. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0457. PMC 2696138. PMID 19091687.

- ^ a b Prieto, L.; MacÍas, D.; Peliz, A.; Ruiz, J. (2015). "Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis) in the Mediterranean: A permanent invasion or a casual appearance?". Scientific Reports. 5: 11545. Bibcode:2015NatSR...511545P. doi:10.1038/srep11545. PMC 4480229. PMID 26108978.

- ^ Mapstone, Gillian M. (2014). "Global Diversity and Review of Siphonophorae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa)". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e87737. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987737M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087737. PMC 3916360. PMID 24516560.

- ^ Munro, Catriona; Siebert, Stefan; Zapata, Felipe; Howison, Mark; Damian-Serrano, Alejandro; Church, Samuel H.; Goetz, Freya E.; Pugh, Philip R.; Haddock, Steven H.D.; Dunn, Casey W. (2018). "Improved phylogenetic resolution within Siphonophora (Cnidaria) with implications for trait evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 127: 823–833. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.06.030. PMC 6064665. PMID 29940256.

- ^ Pugh, P.R. (1984). "The diel migrations and distributions within a mesopelagic community in the North East Atlantic. 7. Siphonophores". Progress in Oceanography. 13 (3–4): 461–489. Bibcode:1984PrOce..13..461P. doi:10.1016/0079-6611(84)90016-8.

- ^ Dunn, Casey W.; Pugh, Philip R.; Haddock, Steven H. D. (2005). "Molecular Phylogenetics of the Siphonophora (Cnidaria), with Implications for the Evolution of Functional Specialization". Systematic Biology. 54 (6): 916–935. doi:10.1080/10635150500354837. PMID 16338764.

- ^ MacKie, G.O.; Pugh, P.R.; Purcell, J.E. (1988). Siphonophore Biology. Advances in Marine Biology. 24. pp. 97–262. doi:10.1016/S0065-2881(08)60074-7. ISBN 9780120261246.

- ^ Araya, Juan Francisco; Aliaga, Juan Antonio; Araya, Marta Esther (2016). "On the distribution of Physalia physalis (Hydrozoa: Physaliidae) in Chile". Marine Biodiversity. 46 (3): 731–735. doi:10.1007/s12526-015-0417-6. S2CID 2646975.

- ^ Copeland, D. Eugene (1968). "Fine Structures of the Carbon Monoxide Secreting Tissue in the Float of Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis L.)". Biological Bulletin. 135 (3): 486–500. doi:10.2307/1539711. JSTOR 1539711.

- ^ Herring, Peter J. (1971). "Biliprotein coloration of Physalia physalis". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry. 39 (4): 739–746. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(71)90099-X.

- ^ Lane, Charles E. (2006). "The Toxin of Physalia Nematocysts". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 90 (3): 742–750. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb26418.x. PMID 13758711. S2CID 44654850.

- ^ Larimer, James L.; Ashby, Ebert A. (1962). "Float gases, gas secretion and tissue respiration in the Portuguese man-of-war,Physalia". Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 60: 41–47. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030600106.

- ^ Totton, A. K.; MacKie, G. O. (1956). "Dimorphism in the Portuguese Man-of-War". Nature. 177 (4502): 290. Bibcode:1956Natur.177..290T. doi:10.1038/177290b0. S2CID 4296257.

- ^ Wilson, Douglas P. (1947). "The Portuguese Man-of-War, Physalia Physalis L., in British and Adjacent Seas" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 27 (1): 139–172. doi:10.1017/s0025315400014156. PMID 18919646.

- ^ Wittenberg, Jonathan B. (1960). "The Source of Carbon Monoxide in the Float of the Portuguese Man-of-War, Physalia Physalis L". Journal of Experimental Biology. 37 (4): 698–705. doi:10.1242/jeb.37.4.698.

- ^ Wittenberg, JB; Noronha, JM; Silverman, M. (1962). "Folic acid derivatives in the gas gland of Physalia physalis L". Biochemical Journal. 85: 9–15. doi:10.1042/bj0850009. PMC 1243904. PMID 14001411.

- ^ Woodcock, A. H. (1956). "Dimorphism in the Portuguese Man-of-War". Nature. 178 (4527): 253–255. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..253W. doi:10.1038/178253a0. S2CID 4297968.

- ^ Yanagihara, Angel A. (2002). Hydrobiologia. 489: 139–150. doi:10.1023/A:1023272519668. S2CID 603421. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Bardi, J. & Marques, A. C. (2007)" Taxonomic redescription of the Portuguese man-of-war, Physalia physalis (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophorae, Cystonectae) from Brazil". Iheringia Ser. Zool. 97: 425–433

- ^ Mackie, G. O. (1960) "Studies on Physalia physalis (L.). Part 2. Behavior and histology". Discovery Reports. 30: 371–407.

- ^ Okada, Y. K. (1932) "Développement post-embryonnaire de la Physalie Pacifique". Mem. Coll. Sci. Kyoto Imp. Univ., Ser. B, Biol, 8: 1–27.

- ^ Totton, A. K. (1960) "Studies on Physalia physalis (L.). Part 1. Natural history and morphology". Discovery Reports, 30: 301–368.

- ^ a b Totton, A. and Mackie, G. (1960) "Studies on Physalia physalis", Discovery Reports, 30: 301–407.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee, Daniel; Schaeffer, Amandine; Groeskamp, Sjoerd (1 October 2021). "Drifting dynamics of the bluebottle (Physalia physalis)". Ocean Science. Copernicus GmbH. 17 (5): 1341–1351. doi:10.5194/os-17-1341-2021. ISSN 1812-0792.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Daw S., Lawes, J., Cooney, N., Ellis, A. and Strasiotto, L. (2020) "National Coastal Safety Report", Technical report, Surf Life Saving Australia.

- ^ a b c d "Physalia physalis, Portuguese man-of-war". Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Bardi, Juliana; Marques, Antonio C (2007). "Taxonomic redescription of the Portuguese man-of-war, Physalia physalis (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophorae, Cystonectae) from Brazil" (PDF). Iheringia, Sér. Zool. Brazil: Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 97 (4): 425–433. doi:10.1590/S0073-47212007000400011. ISSN 1678-4766. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-29.

- ^ Wittenberg, Jonathan B. (1960-01-12). "The Source of Carbon Monoxide in the Float of the Portuguese Man-of-War, Physalia physalis L" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 37 (4): 698–705. doi:10.1242/jeb.37.4.698. ISSN 0022-0949. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ a b "Portuguese Man-of-War". National Geographic Animals. National Geographic. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ a b c "Portuguese Man-of-War". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ^ NOAA (27 July 2015). "What is a Portuguese Man o' War?". National Ocean Service. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Updated 10 October 2017

- ^ a b Dunn, Casey. "Colonial organization". Siphonophores. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Polyp and medusa body shapes". Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Manatū Taonga/Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "What is a Portuguese Man o' War?". NOAA. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Portuguese Man-O'-War". britishseafishing.co.uk. 24 April 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Clark, F. E.; C. E. Lane (1961). "Composition of float gases of Physalia physalis". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 107 (3): 673–674. doi:10.3181/00379727-107-26724. PMID 13693830. S2CID 2687386.

- ^ "Dangerous jellyfish wash up". BBC News. 2008-08-18. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-09-07./

- ^ "Man-of-war spotted along coast in Cornwall and Wales". BBC. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ a b Totton, A. and Mackie, G. (1960) "Studies on Physalia physalis", Discovery Reports, 30: 301–40.

- ^ a b Woodcock, A. H. (1944) "A theory of surface water motion deduced from the wind-induced motion of the Physalia", J. Marine Res., 5: 196–205.

- ^ a b Woodcock, A. H. (1956). "Dimorphism in the Portuguese man-of-war". Nature. 178 (4527): 253–255. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..253W. doi:10.1038/178253a0. S2CID 4297968.

- ^ Iosilevskii, G.; Weihs, D. (2009). "Hydrodynamics of sailing of the Portuguese man-of-war Physalia physalis". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 6 (36): 613–626. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0457. PMC 2696138. PMID 19091687.

- ^ a b Ferrer, Luis; Pastor, Ane (2017). "The Portuguese man-of-war: Gone with the wind". Regional Studies in Marine Science. 14: 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.rsma.2017.05.004.

- ^ Prieto, L.; Macías, D.; Peliz, A.; Ruiz, J. (25 June 2015). "Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis) in the Mediterranean: A permanent invasion or a casual appearance?". Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 5 (1). doi:10.1038/srep11545. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Headlam, Jasmine L.; Lyons, Kieran; Kenny, Jon; Lenihan, Eamonn S.; Quigley, Declan T.G.; Helps, William; Dugon, Michel M.; Doyle, Thomas K. (2020). "Insights on the origin and drift trajectories of Portuguese man of war (Physalia physalis) over the Celtic Sea shelf area". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 246: 107033. Bibcode:2020ECSS..24607033H. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2020.107033. S2CID 224908448.

- ^ Brodie (1989). Venomous Animals. Western Publishing Company.

- ^ Scocchi, Carla; Wood, James B. "Glaucus atlanticus, Blue Ocean Slug". Thecephalopodpage.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Morrison, Sue; Storrie, Ann (1999). Wonders of Western Waters: The Marine Life of South-Western Australia. CALM. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7309-6894-8.

- ^ Sousa, Lara L.; Xavier, Raquel; Costa, Vânia; Humphries, Nicolas E.; Trueman, Clive; Rosa, Rui; Sims, David W.; Queiroz, Nuno (4 July 2016). "DNA barcoding identifies a cosmopolitan diet in the ocean sunfish". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 28762. Bibcode:2016NatSR...628762S. doi:10.1038/srep28762. PMC 4931451. PMID 27373803.

- ^ "Portuguese Man o' War", Oceana.org, Oceana, archived from the original on 2017-04-03, retrieved 2017-04-02

- ^ "Tremoctopus". Tolweb.org. Archived from the original on 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Jones, E.C. (1963). "Tremoctopus violaceus uses Physalia tentacles as weapons". Science. 139 (3556): 764–766. Bibcode:1963Sci...139..764J. doi:10.1126/science.139.3556.764. PMID 17829125. S2CID 40186769.

- ^ a b c Jenkins, R. L. (1983): Observations on the Commensal Relationship of Nomeus gronovii with Physalia physalis. Copeia, Vol. 1983, No. 1 (Feb. 10, 1983), pp. 250-252

- ^ a b c Purcell, J. E. & M. N. Arai (2001): Interactions of pelagic cnidarians and ctenophores with fish: a review.[permanent dead link] Hydrobiologia, May 2001, Volume 451, Issue 1-3, pp 27-44

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press.

- ^ Yanagihara, Angel A.; Kuroiwa, Janelle M.Y.; Oliver, Louise M.; Kunkel, Dennis D. (December 2002). "The ultrastructure of nematocysts from the fishing tentacle of the Hawaiian bluebottle, Physalia utriculus (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophora)" (PDF). Hydrobiologia. 489 (1–3): 139–150. doi:10.1023/A:1023272519668. S2CID 603421. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Auerbach, Paul S. (December 1997). "Envenomations from jellyfish and related species". J Emerg Nurs. 23 (6): 555–565. doi:10.1016/S0099-1767(97)90269-5. PMID 9460392.

- ^ Stein, Mark R.; Marraccini, John V.; Rothschild, Neal E.; Burnett, Joseph W. (March 1989). "Fatal Portuguese man-o'-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation". Ann Emerg Med. 18 (3): 312–315. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(89)80421-4. PMID 2564268.

- ^ a b c Richard A. Clinchy (1996). Dive First Responder. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8016-7525-6. Archived from the original on 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ Fenner, Peter J.; Williamson, John A. (December 1996). "Worldwide deaths and severe envenomation from jellyfish stings". Medical Journal of Australia. 165 (11–12): 658–661. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb138679.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 8985452. S2CID 45032896.

In Australia, particularly on the east coast, up to 10 000 stings occur each summer from the bluebottle (Physalia spp.) alone, with others also from the "hair jellyfish" (Cyanea) and "blubber" (Catostylus). Common stingers in South Australia and Western Australia, include bluebottle, as well the four-tentacled cubozoa or box jellyfish, the "jimble" (Carybdea rastoni)

- ^ "Image Collection: Bites and Infestations: 26. Picture of Portuguese Man of War Sting". www.medicinenet.com. MedicineNet Inc. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

The sting of the Portuguese man-of-war. One of the most painful effects on skin is the consequence of attack by oceanic hydrozoans known as Portuguese men-of-war, which are amazing for their size, brilliant color, and power to induce whealing. They have a small float that buoys them up and from which hang long tentacles. The wrap of these tentacles results in linear stripes, which look like whiplashes, caused not by the force of their sting but from deposition of proteolytic venom toxins, urticariogenic and irritant substances.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; Elston, Dirk M.; Odom, Richard B. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ a b Slaughter, R.J.; Beasley, D.M.; Lambie, B.S.; Schep, L.J. (2009). "New Zealand's venomous creatures". New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1290): 83–97. PMID 19319171. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ Yoshimoto, C.M.; Yanagihara, A.A. (May–June 2002). "Cnidarian (coelenterate) envenomations in Hawai'i improve following heat application". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 96 (3): 300–303. doi:10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90105-7. PMID 12174784. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ Loten, Conrad; Stokes, Barrie; Worsley, David; Seymour, Jamie E.; Jiang, Simon; Isbister, Geoffrey K. (3 April 2006). "A randomised controlled trial of hot water (45 °C) immersion versus ice packs for pain relief in bluebottle stings" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 184 (7): 329–333. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00265.x. PMID 16584366. S2CID 14684627. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-03.

- ^ "Ambulance Fact Sheet: Bluebottle Stings" (PDF). www.ambulance.nsw.gov.au. Ambulance Service of New South Wales. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-14. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ Exton, D.R. (1988). "Treatment of Physalia physalis envenomation". Medical Journal of Australia. 149 (1): 54. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1988.tb120494.x. PMID 2898725. S2CID 20299200.

- ^ a b Wilcox, Christie L.; Headlam, Jasmine L.; Doyle, Thomas K.; Yanagihara, Angel A. (May 22, 2017). "Assessing the Efficacy of First-Aid Measures in Physalia sp. Envenomation, Using Solution- and Blood Agarose-Based Models". Toxins. 9 (5): 149. doi:10.3390/toxins9050149. PMC 5450697. PMID 28445412.

- ^ "SOEST scientists scrutinize first aid for man o' war stings".

- ^ "IPMA - Detalhe noticia". www.ipma.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

Further reading[]

- Mapstone, Gillian (February 6, 2014). "Global Diversity and Review of Siphonophorae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa)". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e87737. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987737M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087737. PMC 3916360. PMID 24516560.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Physalia physalis (Portuguese man o' war). |

Data related to Physalia physalis at Wikispecies

Data related to Physalia physalis at Wikispecies- Siphonophores.org General information on siphonophores, including the Portuguese man-of-war

- National Geographic: Portuguese Man-of-War

- Life In The Fast Lane: Blue bottle

- Portuguesemanofwar.com: Real Stories, Real People, Real Encounters.

- Physaliidae

- Cystonectae

- Cnidarians of the Atlantic Ocean

- Cnidarians of the Indian Ocean

- Cnidarians of the Pacific Ocean

- Cnidarians of the Caribbean Sea

- Animals described in 1758

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

- Venomous animals