Positioning (marketing)

| Marketing |

|---|

Positioning refers to the place that a brand occupies in the minds of the customers and how it is distinguished from the products of the competitors and different from the concept of brand awareness. In order to position products or brands, companies may emphasize the distinguishing features of their brand (what it is, what it does and how, etc.) or they may try to create a suitable image (inexpensive or premium, utilitarian or luxurious, entry-level or high-end, etc.) through the marketing mix. Once a brand has achieved a strong position, it can become difficult to reposition it.

Positioning is one of the most powerful marketing concepts. Originally, positioning focused on the product and with Al Ries and Jack Trout grew to include building a product's reputation and ranking among competitor's products. Schaefer and Kuehlwein extend the concept beyond material and rational aspects to include 'meaning' carried by a brand's mission or myth.[1] Primarily, positioning is about "the place a brand occupies in the mind of its target audience".[2][3] Positioning is now a regular marketing activity or strategy. A national positioning strategy can often be used, or modified slightly, as a tool to accommodate entering into foreign markets.[2][4]

The origins of the positioning concept are unclear. Scholars suggest that it may have emerged from the burgeoning advertising industry in the period following World War I, only to be codified and popularised in the 1950s and 60s. The positioning concept became very influential and continues to evolve in ways that ensure it remains current and relevant to practising marketers.

Definitions[]

David Ogilvy noted that while there was no real consensus as to the meaning of positioning among marketing experts, his definition is "what a product does, and who it is for". For instance, Dove has been successfully positioned as a bar of soap for women with dry hands, vs. a product for men with dirty hands.[5]

Al Ries and Jack Trout advanced several definitions of positioning. In an article, Industrial Marketing, published in 1969, Jack Trout stated that positioning is a mental device used by consumers to simplify information inputs and store new information in a logical place. He said this is important because the typical consumer is overwhelmed with unwanted advertising, and has a natural tendency to discard all information that does not immediately find a comfortable (and empty) slot in their mind.[6] In Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind, the duo expanded the definition as "an organized system for finding a window in the mind. It is based on the concept that communication can only take place at the right time and under the right circumstances".[7]

Positioning is closely related to the concept of perceived value. In marketing, value is defined as the difference between a prospective customer's evaluation of the benefits and costs of one product when compared with others. Value can be expressed in numerous forms including product benefits, features, style, value for money.[8]

Origins[]

The precise origins of the positioning concept are unclear. Cano (2003), Schwartzkopf (2008), and others have argued that the concepts of market segmentation and positioning were central to the tacit knowledge that informed brand advertising from the 1920s, but did not become codified in marketing textbooks and journal articles until the 1950s and 60s.[9][10]

Al Ries and Jack Trout are often credited with developing the concept of product or brand positioning in the late-1960s with the publication of a series of articles, followed by a book. Ries and Trout, both former advertising executives, published articles about positioning in Industrial Marketing in 1969 and Advertising Age in 1972.[11] By the early 1970s, positioning became a popular word with marketers, especially those in advertising and promotion. In 1981, Ries and Trout published their now-classic book, Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. However, the claim that Ries and Trout devised the concept has been challenged by marketing scholars. According to Stephen A. Fox, Al Ries, and Jack Trout "resurrected the concept and made it their trademark."[12]

Some scholars credit advertising guru, David Ogilvy, with developing the positioning concept in the mid-1950s, at least a decade before Ries and Trout published their now-classic series of articles.[13] In their early writing, Ries and Trout suggest that the positioning concept was widely used in the advertising industry before the 1950s. Ogilvy's writings indicate that he was well aware of the concept and drilled his creative team with this idea from at least the 1950s. Among other things, Ogilvy wrote that "the most important decision is how to position your product",[14] and "Every advertisement is part of the long-term investment in the personality of the brand."[15] Ogilvy is on record as having used the positioning concept in several campaigns in the mid-1950s and early 1960s, well before Ries and Trout published their articles on the positioning. In relation to a Dove campaign launched in 1957, Ogilvy explained, "I could have positioned Dove as a detergent bar for men with dirty hands, but chose instead to position it as a toilet bar for women with dry skin. This is still working 25 years later."[5] In relation to a SAAB campaign launched in 1961, Ogilvy later recalled that "In Norway, the SAAB car had no measurable profile. We positioned it as a car for winter. Three years later it was voted the best car for Norwegian winters."[5]

Yet other scholars have suggested that the positioning concept may have much earlier heritage, attributing the concept to the work of advertising agencies in both the US and the UK in the first decades of the twentieth century. Cano, for example, has argued that marketing practitioners followed competitor-based approaches to both market segmentation and product positioning in the first decades of the twentieth century; long before these concepts were introduced into the marketing literature in the 1950s and 60s.[16] From around 1920, American agency, J. Walter Thompson (JWT), began to focus on developing brand personality, brand image, and brand identity—concepts that are very closely related to positioning. Across the Atlantic, the English agency, W. S. Crawford's Ltd, began to use the concept of 'product personality' and the 'advertising idea' arguing that in order to stimulate sales and create a 'buying habit' advertising had to 'build a definitive association of ideas round the goods'.[17] For example, in 1915 JWT acquired the advertising account for Lux soap. The agency suggested that the traditional positioning as a product for woolen garments should be broadened so that consumers would see it as a soap for use on all fine fabrics in the household. To implement, Lux was repositioned with a more up-market posture and began a long association with expensive clothing and high fashion. Cano has argued that the positioning strategy JWT used for Lux exhibited an insightful understanding of the way that consumers mentally construct brand images. JWT recognised that advertising effectively manipulated socially shared symbols. In the case of Lux, the brand disconnected from images of household drudgery and connected with images of leisure and fashion.[18]

As advertising executives in their early careers, both Ries and Trout were exposed to the positioning concept via their work. Ries and Trout codified the tacit knowledge that was available in the advertising industry; popularising the positioning concept with the publication of their articles and books. Ries and Trout were influential in diffusing the concept of positioning from the advertising community through to the broader marketing community. Their articles were to become highly influential.[19] By the early 1970s, positioning became a popular word with marketers, especially those that were working in the area of advertising and promotion. In 1981 Ries and Trout published their classic book, Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind (McGraw-Hill 1981). The concept enjoys ongoing currency among both advertisers and marketers as suggested by Maggard[3] who notes that positioning provides planners with a valuable conceptual vehicle, which is effectively used to make various strategy techniques more meaningful and more productive.[3]

Several large brands – Lipton, Kraft, and Tide – developed "precisely worded" positioning statements that guided how products would be packaged, promoted, and advertised in the 1950s and 1960s. The article, "How Brands Were Born: A Brief History of Modern Marketing," states, "This marked the start of almost 50 years of marketing where 'winning' was determined by understanding the consumer better than competitors and getting the total 'brand mix' right.[20] This early positioning tactic was focused on the product itself – its "form, package size, and price", according to Al Ries and Jack Trout[3]

The positioning concept continues to evolve. Traditionally called product positioning, the concept was limited due to its focus on the product alone.[21] In addition to the previous focus on the product, positioning now includes building a brand's reputation and competitive standing.[3] John P. Maggard notes that positioning provides planners with a valuable conceptual vehicle for the implementation of more meaningful and productive marketing strategies.[3] Many branding practitioners make positioning a part of brand strategy and even label it as "brand positioning".[22][23] However, in the book Get to Aha! Discover Your Positioning DNA and Dominate Your Competition, Andy Cunningham proposes that branding is actually "derived from positioning; it is the emotional expression of positioning. Branding is the yang to positioning's yin, and when both pieces come together, you have a sense of the company's identity as a whole".[24]

Developing the positioning statement[]

Positioning is part of the broader marketing strategy which includes three basic decision levels, namely segmentation, targeting and positioning, sometimes known as the S-T-P approach:

- Segmentation: refers to the process of dividing a broad consumer or business market, normally consisting of existing and potential customers, into sub-groups of consumers (known as segments)[25]

- Targeting: refers to the selection of a segment or segments that will become the focus of special attention (known as target markets).[26]

- Positioning: refers to an overall strategy that "aims to make a brand occupy a distinct position, relative to competing brands, in the mind of the customer".[27]

In general terms, there are three broad types of positioning: functional, symbolic, and experiential position. Functional positions resolve problems, provide benefits to customers, or get favorable perception by investors (stock profile) and lenders. Symbolic positions address self-image enhancement, ego identification, belongingness and social meaningfulness, and affective fulfillment. Experiential positions provide sensory and cognitive stimulation.[28]

Positioning statement[]

Both theorists and practitioners argue that the positioning statement should be written in a format that includes an identification of the target market, the market need, the product name and category, the key benefit delivered and the basis of the product's differentiation from any competing alternatives.[29] A basic template for writing positioning statements is as follows: "For (target customer) who (statement of the need or opportunity), the (product name) is a (product category) that (statement of key benefit – that is, compelling reason to buy). Unlike (primary competitive alternative), our product (statement of primary differentiation)."[29] An annotated example of how this positioning statement might be translated for a specific application appears in the text-box that follows.

| Annotated example of a Positioning Statement[30] | Volvo |

|---|---|

|

To upper income, other brand switcher car buyers [target audience]; Volvo is a differentiated brand of prestige automobiles [marketing strategy], That offers the benefits of safety [problem removal] as well as prestige [social approval]. The advertising for Volvo, should emphasize safety and performance [message strategy] and Must mention prestige as an entry ticket to the category And will downplay its previous family-car orientation in the interest of appealing to a broader range of users. |

Within the prestige vehicle category, Volvo positions itself as a car offering superior safety and performance |

Notes: Annotations, added in square brackets, were not in the original positioning statement, but are included here to show how the general format and elements of positioning statements described in the preceding discussion, have been applied to the specific example, which in this case is Volvo.

Differentiation vs positioning[]

Differentiation is closely related to the concept of positioning. Differentiation is how a company's product is unique, by being the first, least expensive, or some other distinguishing factor. A product or brand may have many points of difference, but they may not all be meaningful or relevant to the target market. Positioning is something (a perception) that happens in the minds of the target market whereas differentiation is something that marketers do, whether through product design, pricing or promotional activity.[31]

Strategies[]

To be successful in a particular market a product must occupy an "explicit, distinct and proper place in the minds of all potential and existing consumers".[33] It has to also be relative to other rival products with which the brand competes.[33] This may require considerable research of customer perceptions and competitor activity in order to ensure that the points of difference are meaningful in the minds of customers. Perceptual mapping (discussed below) is often used for this type of research.

Visibility and recognition is what product positioning is all about as the positioning of a product is what the product represents for a buyer the business is targeting. As markets become increasingly competitive, buyer have more purchase choices, and the process of setting one brand apart from rival brands is critical success factor.[33] It is vital that a product or service needs to have a clear identity and placement to the needs of the consumers targeted as they will not only purchase the product, but can warrant a larger margin for the company through increased added value.[33]

A number of different positioning strategies have been cited in the marketing literature:[34]

| Approaches | Example |

|---|---|

| Preemptive positioning

(Being the first to claim a benefit or feature) |

Smith's Chips – the original and still the best |

| Superlative positioning

(Being the best or exhibiting some type of superiority) |

The burgers are better at Hungry Jack's |

| Exclusive positioning

(Being a member of an exclusive club or group) |

XYZ Ltd – a Fortune 500 company |

| Positioning within a category

(Strong registration of both category and brand) |

Within the prestige car category, Volvo is the safe alternative |

| Positioning by competitor strategy

(Use competitor's strategy as a reference point) |

Avis – we're number two, so we try harder |

| Positioning according to product benefit(s)

(Emphasize a problem, need or benefit where the firm |

Toothpaste with whitening, tartar control or enamel protection (or multiple benefits) |

| Positioning according to product attribute | Dove is one-quarter moisturiser |

| Positioning for usage occasion

(Can be associated with seasonal products) |

Cadbury Roses Chocolates—for gift giving or saying, 'Thank-you' |

| Positioning along price lines | A premium brand or an economy brand |

| Positioning for a user or user group | Johnson & Johnson range of baby products (e.g., No Tears Shampoo) |

| Positioning by cultural symbols | Australia's Easter Bilby (as a culturally appropriate alternative to the Easter Bunny) used as the shape of Easter chocolates |

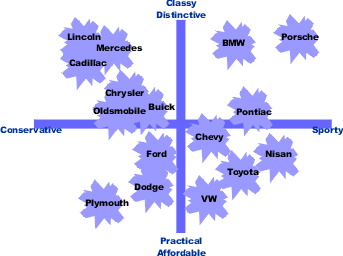

Perceptual mapping[]

To identify suitable positions that a company or brand might occupy in a given market, analysts often turn to techniques such as perceptual mapping or correspondence analysis. Perceptual maps are a diagrammatic representation of consumers' mental perceptions of the relative place various brands occupy within a category. Traditionally perceptual mapping selects two variables that are relevant to consumers (often, but not necessarily, price and quality) and then asks a sample of the market to explain where they would place various brands in terms of the two variables. Results are averaged across all respondents, and results are plotted on a graph to indicate how the average member of the population views the brand that make up a category and how each of the brands relates to other brands within the same category. While perceptual maps with two dimensions are common, multi-dimensional maps are also used. A key advantage of perceptual mapping is that it can identify gaps in the market which the firm may choose to 'own.'

|

|

|

| Simple perceptual map of U.S. motor vehicle category (using two variables) | Multi-dimensional perceptual map of analgesics category | Perceptual map for hypothetical product category |

Algorithms used in positioning analysis[]

The following statistical procedures have been found to be useful in carrying out positioning analysis:

- Cluster analysis[35] including overlapping clustering[36]

- Correspondence analysis[37]

- Conjoint analysis[38]

- Multidimensional scaling especially non-metric scaling (NMS)[39]

- Multivariate analysis[40]

Repositioning[]

The right positioning strategy at the right time can help a brand build a powerful image in the mind of consumer(s).[41] From time to time, the current positioning strategy fails to resonate. This could be due to new market entrants, changed customer preferences, structural change within the target market (such as ageing, segment creep) or simply that customers have forgotten about a brand and its position. When this happens, the company may need to consider a number of options:[42]

- * Strengthen current positioning: reinforce the concepts of features that led to customers adopting a favourable view in the first instance

- * Establish a new position: look for suitable niches where customers are underserviced and occupy that space

- * Reposition (or de-position): change the way customers think about the product or brand, usually through comparative advertising

Repositioning involves a deliberate attempt to alter the way that consumers view a product or brand. Repositioning can be a high risk strategy, but sometimes there are few alternatives.[43]

Fishbein and Rosenberg's attitude models[3][44] indicate that it is possible for a business to influence and change the positioning of the brand by manipulating various factors that will affect a consumer's attitude. Research on persons' attitudes suggests that a brand's position in a prospective consumer's mind is likely to be determined by the "combined total of a number of product characteristics such as the price, quality, durability, reliability, colour, and flavour".[3] The consumer places important weights on each of these product characteristics and it can be possible by using things such as promotional efforts to realign the weights of price, quality, durability, reliability, colour and flavour of which can then help adjust the position of a brand in the mind of the prospective consumer.[3][44] Companies engaging in repositioning can choose to downplay some points of difference and emphasise others.

Repositioning a company[]

In volatile markets, it can be necessary – even urgent – to reposition an entire company, rather than just a product line or brand. When Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley suddenly shifted from investment to commercial banks, for example, the expectations of investors, employees, clients and regulators all needed to shift, and each company needed to influence how these perceptions changed. Doing so involves repositioning the entire firm. This is especially true of small and medium-sized firms, many of which often lack strong brands for individual product lines. In a prolonged recession, business approaches that were effective during healthy economies often become ineffective and it becomes necessary to change a firm's positioning. Upscale restaurants, for example, which previously flourished on expense account dinners and corporate events, may for the first time need to stress value as a sale tool.

Repositioning a company involves more than a marketing challenge. It involves making hard decisions about how a market is shifting and how a firm's competitors will react. Often these decisions must be made without the benefit of sufficient information, simply because the definition of "volatility" is that change becomes difficult or impossible to predict.

See also[]

Advertising models[]

- Overview of theories of advertising effects

- AISDALSLove

- DAGMAR marketing

- Elaboration likelihood model (article)

References[]

- ^ Kuehlwein, JP; Schaefer, Wolfgang (2015). Rethinking Prestige Branding - Secrets of the Ueber-Brands. London: Kogan Page. pp. 15–16, 115–116. ISBN 978-0749470036.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Andrei, P; Ecaterina, B, R; Ionut, T. C (2010). "Does Positioning Have a Place in the Minds of our Students?". Annals of the University of Oradea, Economic Science Series.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Maggard, John P. (1976-01-01). "Positioning Revisited". Journal of Marketing. 40 (1): 63–66. doi:10.2307/1250678. JSTOR 1250678.

- ^ Sandra Bell (March 29, 2008). International Brand Management of Chinese Companies: Case Studies on the Chinese Household Appliances and Consumer Electronics Industry Entering US and Western European Markets. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-7908-2030-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c David Ogilvy (1983). Ogilvy on Advertising. Vintage Books. p. 12.

- ^ Jack Trout (1969). "Positioning" is a game people play in today's me-too market place". Industrial Marketing: 51–55.

- ^ Al Ries; Jack Trout (2001). Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-137358-6.

- ^ marketing. 2011. p. 147.

- ^ Schwarzkopf, S., "Turning Trade Marks into Brands: how Advertising Agencies Created Brands in the Global Market Place, 1900-1930" CGR Working Paper, Queen Mary University, School of Business and Management Centre for Globalization Research London, 18 August 2008

- ^ Cano, C., "The Recent Evolution of Market Segmentation Concepts and Thoughts Primarily by Marketing Academics," in E. Shaw (ed) The Romance of Marketing History, Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), Boca Ranton, FL, AHRIM, 2003

- ^ T. Ellson (March 16, 2004). Culture and Positioning as Determinants of Strategy: Personality and the Business Organization. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-230-50981-8.

- ^ Stephen R. Fox (1984). The Mirror Makers: A History of American Advertising and Its Creators. University of Illinois Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-252-06659-7.

- ^ Urde, M. and Koch, C., "Market and brand-oriented schools of positioning", Journal of Product & Brand Management, vol. 23, no. 7, 2014, pp 478-490

- ^ Ogilvy, D., Confessions of an Advertising Man, 1963

- ^ Ogilvy, D, "The Image and the brand: a new approach to creative operations," Speech given at AAAA Luncheon in Chicago, 4 October 4, 1955 and cited in Schwarzkopf, S., "Turning Trade Marks into Brands: how Advertising Agencies Created Brands in the Global Market Place, 1900-1930" CGR Working Paper, Queen Mary University, London, 18 August 2008

- ^ Cano, C., "The Recent Evolution of Market Segmentation Concepts and Thoughts Primarily by Marketing Academics," in E. Shaw (ed.), The Romance of Marketing History: Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), Boca Ranton, FL: AHRIM, 2003, p.18

- ^ Schwarzkopf, S., Turning Trade Marks into Brands: how Advertising Agencies Created Brands in the Global Market Place, 1900-1930, CGR Working Paper, Queen Mary University, London, 18 August 2008, p. 22

- ^ Cano, C., "The Recent Evolution of Market Segmentation Concepts and Thoughts Primarily by Marketing Academics," in E. Shaw (ed.), The Romance of Marketing History: Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), Boca Ranton, FL: AHRIM, 2003, pp 16-18

- ^ Enis, B. and Cox,K., Marketing classics: a selection of influential articles, Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 1969

- ^ Marc de Swaan Aron (October 3, 2011). "How Brands Were Born: A Brief History of Modern Marketing". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Al Ries; Jack Trout (January 3, 2001). Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-07-170587-5.

- ^ "A Simple Definition of Brand Positioning". The Branding Journal. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ "Brand Positioning Strategy". Equibrand Consulting. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ Cunningham, Andy (October 17, 2017). Get to Aha! Discover Your Positioning DNA and Dominate Your Competition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-260-03120-1.

- ^ Moutinho, L., "Segmentation, Targeting, Positioning and Strategic Marketing," Chapter 5 in Strategic Management in Tourism, Moutinho, L. (ed), CAB International, 2000, pp. 121–166

- ^ Marketing Insider, "Evaluating Market Segments", Online: https://marketing-insider.eu/marketing-explained/part-i-defining-marketing-and-the-marketing-process/market-targeting/

- ^ Business Dictionary, http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/positioning.html

- ^ Mulvey, Michael (January 2009). "Experiential positioning: Strategic differentiation of customer-brand relationships". Innovative Marketing. 5 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Geoffrey Moore (1991). Crossing the Chasm. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0887305191.

- ^ Volvo Creative Brief, in Rossiter, J. and Percy, L., Advertising Communications and Promotion Management, N.Y., McGraw-Hill, 1997, p. 159

- ^ Charles Lamb (2012). Essentials of Marketing (7e ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. pp. 279–82. ISBN 978-0-538-47834-2.

- ^ Kaschny, Martin (2018). Innovation and Transformation. Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-319-78524-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ostasevičiūtė, R; Šliburytė, L (February 2008). "Theoretical Aspects of Product Positioning in the Market". Engineering Economics.

- ^ Rogers, S.C., Marketing Strategies, Tactics, and Techniques: A Handbook for Practitioners, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, pp 90-92; Belch, G., Belch, M.A, Kerr, G. and Powell, I., Advertising and Promotion Management: An Integrated Marketing Communication Perspective, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, Australia, 2009, pp 205-206

- ^ Hoffman, D.L. and Franke, G.R., "Correspondence analysis: graphical representation of categorical data in marketing research," Journal of Marketing Research, 23, 1986, pp 213–227

- ^ Phipps, A., Carroll, J.D. and Wind, Y.J., "Overlapping Clustering: A New Method for Product Positioning," Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 3 1981, pp. 310-317

- ^ Wena, C.H. and Chen, W.Y., "Using multiple correspondence cluster analysis to map the competitive position of airlines", Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 17, No. 5, 2011, pp 302–304

- ^ Paul E. Green and Abba M. Krieger Conjoint analysis with product-positioning applications Chapter 10 in Handbook in Operations Research and Management Science, Vol. 5 [Marketing], Eliashberg,j. and Lilien, G.L. (eds), Elsevier, 1993 https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0927-0507(05)80023-4, pp 467–515

- ^ Moutinho, L., "Segmentation, Targeting, Positioning and Strategic Marketing," Chapter 5 in Strategic Management in Tourism, Moutinho, L. (ed), CAB International, 2000, pp 121-166

- ^ Mazanec, J.A., "Positioning analysis with self-organizing maps: An exploratory study on luxury hotels", The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 6, 1995, pp 80-95

- ^ Sair, S. A (2014). "Consumer Psyche and Positioning Strategies". Pakistan Journal of Commerce & Social Sciences.

- ^ Blythe, J., Key Concepts in Marketing, Sage, 2009, p. 171

- ^ Strydom, J., Introduction to Marketing, Juta and Company, 2005. pp 77-78

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ray, Michael L. (1973-01-01). "A Decision Sequence Analysis of Developments in Marketing Communication". Journal of Marketing. 37 (1): 29–38. doi:10.2307/1250772. JSTOR 1250772.

- Brand management

- Marketing research

- Marketing strategy

- Market segmentation

- Product management