Principality of the Pindus

| Part of a series on |

| Aromanians |

|---|

|

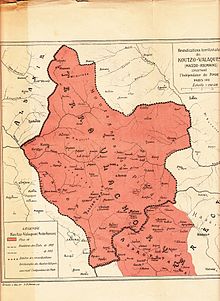

The Principality of the Pindus (Aromanian: Printsipat di la Pind; Greek: Πριγκιπάτο της Πίνδου; Italian: Principato del Pindo; Romanian: Principatul de Pind) is the name used in literature to describe the attempt and proposal to create an autonomous canton under the protection of Italy during World War I, in July and August 1917, from the Aromanian population of Samarina (Samarina, Xamarina or San Marina) and other villages of the Pindus mountains of Northern Greece during the short period of occupation by Italy of the district of Gjirokastra (Ljurocastru, Iurucasta or Iurucast) and regions of Epirus.[1] The attempt was not successful and no such principality was ever officially formed.[2] A declaration was made after the arrival of Italian troops in Samarina. In the immediate withdrawal of Italians a few days later, Greek troops appeared without meeting any resistance.[2]

Since then there was no mention of any similar activity until 1941 when the territory of Greece were occupied by Italy, Germany and Bulgaria under the World War II. At that time, Alcibiades Diamandi, an Aromanian residing in Samarina who also took part in the events of 1917, was active with an organization called in later literature with the name of the Roman Legion. As part of the activity of the organization in the areas of mainly Thessaly (and Epirus, and West Macedonia), it was mentioned as an intention of Diamandi to create a semi-independent entity by the name "Principality of the Pindus" or "Independent State of Pindos" or "Canton". The Roman Legion was never able to assert itself over the Aromanians whom it supposedly represented, nor over the local population until its de facto disbandment in 1943 due to the activity of the Greek Resistance and the Italian capitulation, leaving them without real support from the German command.[3] In other sources, no name is assigned to the events of 1917 in the Pindus.[4][5]

Name[]

The name "Principality of the Pindus" was given retrospectively and is used in bibliography literature mainly about the events of 1917 in Samarina. It was also used for the activity of Diamanti 25 years later, the so-called Roman Legion in 1942–1943. In sources closer to the events it is not used in 1917 nor in the period from 1942 to 1943. Indicatively, 12 years after the events in 1929, Nicolae Zdrulla wrote in the journal Revista Aromânească (Volume 1, No. 2) issued in Bucharest an article entitled "Mișcarea aromânilor din Pind în 1917" ("The movement of the Aromanians of the Pindus in 1917").[6] An archival study published in 2007 with documents of the same period (telegrams of the Aromanians to head of states of that time and correspondence of the Italian and Romanian Consulates) was entitled "The events of July–August 1917 in the region of the Pindus. The effort to create an independent state of Aromanians"[2] mentions the word "Principality" only in the introduction, while there is no reference to it to the documents of the time recorded in this archival study.

Background[]

Since Romania's formation in 1859, it tried to win influence over the Aromanian (and also the Megleno-Romanian) population of the Ottoman Empire. In the 1860s, it funded the activity of Apostolos Margaritis who founded Romanian schools in the Ottoman territories of Epirus and Macedonia since the Aromanian language has much in common with the Romanian language. Romania, with the support of Austria-Hungary, succeeded in the acceptance of the Aromanians as a separate millet with the decree (irade) of 22 May 1905 by Sultan Abdulhamid, so the Ullah Millet ("Vlach Millet", for the Aromanians) could have their own churches and schools.[4] This was a diplomatic success of Romania in European Turkey in the last part of the 19th century.[7]

Romania then funded the construction and operation of many schools in the wider region of Macedonia and Epirus. These schools have continued their operation even when some of the territories of the region of Macedonia and Thrace passed to Greek authority in 1912. Their financing by Romania continued in 1913 with the agreement of the then Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos.[5] In such Romanian schools, there was a coordinated effort to promote the idea of Romanian identity among Aromanians. Graduates of these schools who wanted to continue their education usually went to educational institutions in Romania.

Posteriorly, during the First World War, in 1916, Albania, including Northern Epirus, was split between the Kingdom of Italy which occupied Gjirokastra[8] (Ljurocastru, Iurucasta or Iurucast) and France which occupied Korçë (Curceauã, Curceao or Curciau), while in northern and central Albania were occupied by troops of Austria-Hungary.

On 10 December 1916, the French founded the Autonomous Albanian Republic of Korçë. In response, Austria-Hungary went on proclamation of independence of Albania as a protectorate on 3 January 1917, in Shkodra, while on 23 June 1917, the Italians proclaimed the Italian protectorate over Albania in Gjirokastra.[9] Then the Italian forces advanced and they captured Ioannina (Ianina or Enine).

In this environment of occupation and fragmentation of territories in Southern Albania and Northwestern Greece, Italian troops occupied Samarina (Samarina, Xamarina or San Marina) and other villages of the Pindus for a few days at the end of August 1917 to the first two days of September 1917.[10]

Proposals and attempts in 1917[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In 1917, during the occupation of the territories of Albania and Northern Epirus, the Italians tried to win over the Aromanians to convert Aromanian-Romanian relations in favor of Italy, based on historical and linguistic relations and to change the pro-Romanian Aromanians into pro-Italian Aromanians.[7][11]

In the brief period of Italian occupation of southern Albania, when Italian forces also entered Greek territory in 1917, Aromanians from several villages of the Pindus mountain requested autonomy under the protection of Italy, turning to Romania for help. Letters were sent to several countries, from mayors and representatives of 13 villages.[2] A proclamation was sent on 29 August 1917, from Samarina signed by seven representatives, who had the role of a temporary committee and requested assistance and protection from the Italian Consulate of Ioannina.[2] One of the members of the provisionary committee, Alcibiades Diamandi, went to Ioannina to get an answer. There was an immediate response the next day from the Romanian and the Italian consulates: A clear answer that these actions were wrong and inappropriate, were not approved by anyone, and could not be supported by any party.[2]

One day later, the Italian army departed from Greek territory. From 3 to 7 September the Greek forces entered all the villages unopposed and, on 7 September, they arrested seven men in Samarina, giving an end to the events.[2][7]

These events are described in later bibliography as an attempt to form a "Principality of the Pindus", while in other sources, no name is assigned to the events of 1917.[4][5][7]

Later, in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and 1920, an Aromanian delegation requested autonomy for the Aromanians.[12]

Villages and people involved[]

A letter to the Prime Minister of Romania Ion C. Brătianu, sent on 27 July 1917, was signed by mayors and notables of the following villages:[2] Samarina, Avdella (Avdhela), Perivoli (Pirivoli), Vovousa (Bãiasa, Baiesa or Baiasa), Metsovo (Aminciu), Konitsa (Conitsa), (Padzes), Kranea (Turia), Distrato (Briaza), (Laca), Iliochori (Dovrinovo), (Armata) and Smixi (Zmixi).

Furthermore, the assistance request to the Italian Consulate was signed by the seven members of the Provisional Committee:[2]

- Doctor Dimitrie Diamandi

- Ianaculi Dabura

- Mihali Teguiani

- Tachi Nibi

- Zicu Araia

- Alcibiadi Diamandi

- Sterie Caragiani

The persons arrested by the Greek authorities in Samarina on 8 September 1917, were:[2]

- D-l Zicu Araia, school master of the Romanian school of Samarina

- Guli Papagheorghe, teacher of the Romanian school of Samarina

- Ianache Dabura, ex-mayor of Samarina

- Gherassim Zica, inhabitant of Samarina

- Ianachi Zuchi, inhabitant of Samarina

- Costachi Surbi, inhabitant of Samarina

Italian occupation and Roman Legion of 1941–1943[]

The Aromanians were part of the projects for the dismemberment of Greece set up by the Italians. When the 11th Army occupied the areas in 1941, their commanders received orders by Palazzo Chigi (the seat of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time) to survey each village recording their ethnicity and its attitude towards the occupiers, finding that most Aromanians absorbed and assimilated into the Greek community with the exception of some groups who were recorded as anti-Bulgarian, anti-Greek, pro-Italian and pro-Romanian.[13] A pre-war dossier for the Italian government on the subject of the Aromanians promoted the idea that they were descendants from the Ancient Romans and that the Aromanians had taken shelter in the Pindus Mountains against barbarian invasions, to be used at the appropriate moment.[14]

After the fall of Greece to the Germans in spring 1941 and the division of the country among the Axis powers, Alcibiades Diamandi created a collaborationist organisation known as the Roman Legion, with the support of the Italian occupation authorities and promoted the idea of an Aromanian canton or semi-independent state, called several decades later by the name "Principality of Pindus" that would encompass northwestern Greece. Diamandi also met the Greek collaborationist Prime Minister, Georgios Tsolakoglou, but Tsolakoglou refused to accommodate his demands. In reality Italian "military authorities refused to permit any form of self-administration by the Aromanians in the awareness that their irredentist aspirations, or appeals for annexation to Italy, were a masquerade by a minority movement seeking political and economic revenge".[15]

From mid-1942 on, the armed Greek Resistance also made its presence felt, fighting against the Italians and their collaborators and the leader of the Roman Legion, Diamandi, left for Romania in 1942, to be followed by his second in command and successor Nicolaos Matussis in 1943.[16]

Whatever authority the Roman Legion exercised, it practically ceased to exist after the Italian capitulation in September 1943, when the control of Central Greece was taken over by the German army.

References[]

- ^ Autonomy of the Pindus Principate

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Evenimentele din lunile iulie-august 1917 în regiunea Munților Pind – încercare de creare a uneistatalități a aromânilor. documente inedite și mărturii. studiu istoriografic și arhivistic, Stoica Lascu, Revista Română de Studii Eurasiatice, Anul III, No. 1-2/2007

- ^ (in Greek)The capitulation of Italy from Rizospastis newspaper, 7 September 2003

- ^ a b c The ethnicity of Aromanians after 1990: the Identity of a Minority that Behaves like a Majority, Thede Kahl, Ethnologia Balkanica, Vol. 6 (2002), σελ. 148

- ^ a b c The Politics of Nation-Building: Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities, Harris Mylonas, Cambridge University Press, 2013, σελ. 134

- ^ Nicolae Zdrulla, Mișcarea aromânilor din Pind în 1917, Revista Aromânească, vol 1, no. 2, București, 1929, pp. 162–168

- ^ a b c d Chenoweth, Erica; Lawrence, Adria (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-state Actors in Conflict. MIT Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780262014205.

- ^ Armies in the Balkans 1914-18, Nigel Thomas, Osprey Publishing, 2001, p. 17

- ^ Jaume Ollé (15 July 1996). "Republic of Korçë (1917–1918)". Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

On 23 June 1917, Italy proclaimed the independence of Albania under her protectorate, justifying this with the French precedent in Korçë. Austria-Hungary had done it before on 3 January 1917.

- ^ (in Greek) Μανόλης Γλέζος Manolis Glezos, Εθνική αντίσταση, 1940–1945, τόμος 1, Στοχαστής, 2006, p. 260

- ^ The Fight for Balkan Latinity, Giuseppe Motta, Proiect Avhdela, p. 10 (data from report of the Italian officer Casoldi entitled: "Note circa la questione valacca" "Note about the Vlach Question" of 29 May 1917

- ^ Motta, Giuseppe (2011). "The Fight for Balkan Latinity. The Aromanians until World War I" (PDF). Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 2 (3): 252–260. doi:10.5901/mjss.2011.v2n3p252. ISSN 2039-2117.

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 105.

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge University Press, 2006. pp. 105-106.

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 326. ISBN 0-521-84515-7

- ^ (in Greek) Η άλλη Ξένη, from the To Vima newspaper

Sources[]

- Arseniou Lazaros, Η Θεσσαλία στην Αντίσταση

- Andreanu, José, Los secretos del Balkan

- Iatropoulos, Dimitri, Balkan Heraldry

- Toso, Fiorenzo, Frammenti d'Europa

- Zambounis, Michael, Kings and Princes of Greece, Athens 2001

- Papakonstantinou Michael, Το Χρονικό της μεγάλης νύχτας (The chronicle of big night)

- Divani, Lena, Το θνησιγενές πριγκιπάτο της Πίνδου. Γιατί δεν ανταποκρίθηκαν οι Κουτσόβλαχοι της Ελλάδας, στην Ιταλο-ρουμανική προπαγάνδα.

- Thornberry, Patrick and Miranda Bruce-Mitford, World Directory of Minorities. St. James Press 1990, page 131.

- Koliopoulos, Giannēs S. (a.k.a. John S. Koliopoulos), Plundered Loyalties: Axis Occupation and Civil Strife in Greek West Macedonia. C. Hurst & Co, 1990. page 86 ff.

- Poulto, Hugh, Who Are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co, 1995. page 111. (partly available online: [1])

- After the War Was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation, and State in Greece By Mark Mazower (partly available online: [2])

- Kalimniou, Dean, Alkiviadis Diamandi di Samarina (in Neos Kosmos English edition, Melbourne, 2006)

- Seidl-Bonitz-Hochegger, Zeitschrift für Niederösterreichischen Gymnasien XIV.

External links[]

- (in Hungarian) A nemlétezők lázadása

- (in French) Open University of Calalonia: Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce

- (in Greek) Η φωνή της γης

- History of the Aromanians

- Aromanian nationalism

- History of Epirus

- States and territories established in 1941

- States and territories disestablished in 1943

- Greece in World War I

- Greece–Romania relations

- Greece–Italy relations

- Separatism in Greece

- Pindus

- Aromanians in Greece