Professor Moriarty

| Professor James Moriarty | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

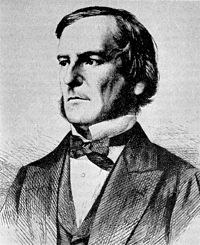

Professor James Moriarty, illustration by Sidney Paget which accompanied the original publication of "The Final Problem" | |

| First appearance | "The Final Problem" (1893) |

| Created by | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | James Moriarty |

| Occupation | Professor of mathematics (former) Criminal mastermind |

| Family | One or two brothers[1] |

| Nationality | British |

Professor James Moriarty is a fictional character that first appeared in the Sherlock Holmes short story "The Final Problem" written by Arthur Conan Doyle and published under the second collection of Holmes short stories, The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, late in 1893. Moriarty was also featured in the fourth and final Sherlock Holmes novel The Valley of Fear but never made direct appearance in the story. Apart from that Holmes mentions him in five other stories, namely "The Adventure of the Empty House", "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder", "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter", "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client" and "His Last Bow". The character was introduced primarily as a narrative device to enable Doyle to kill Sherlock Holmes. Although many adaptations and pastiches give him the first name of James, the first Doyle story to feature him ("The Final Problem") does not give him a first name, whereas the short story "The Adventure of the Empty House" said his first name is James (previously said to be the name of his brother).

Moriarty is a machiavellian, consulting criminal mastermind who does not commit crimes himself but uses his intelligence and network of resources to provide criminals with strategies for their crimes and sometimes protection from the law, all in exchange for a fee or a cut of profit. Holmes likens Moriarty to a spider at the center of a web and calls him the "Napoleon of crime", a phrase Doyle lifted from a Scotland Yard inspector referring to Adam Worth, a real-life criminal mastermind and one of the individuals upon whom the character of Moriarty was based. Despite only twice appearing in Doyle's original stories, later adaptations and pastiches have often given Moriarty greater prominence and treated him as Sherlock Holmes' archenemy.

Appearances in works[]

Professor Moriarty's first appearance occurred in the 1893 short story "The Adventure of the Final Problem" (set in 1891[2]). The story features consulting detective Sherlock Holmes revealing to his friend and biographer Doctor Watson that he has uncovered a secret criminal network responsible for "half that is evil" in London and is on the verge of delivering it a fatal blow. Professor Moriarty is introduced as a criminal mastermind who provides strategy and protection to criminals in exchange for their obedience and a share in their profits. Holmes, by his own account, is originally led to Moriarty by his perception that many of the crimes he investigates are not isolated incidents, but instead the machinations of a vast and subtle criminal organisation. Having now gathered and delivered the appropriate evidence to the police, Holmes knows that the network will face justice in a few days, but the mastermind and his trusted lieutenants want to kill him before they are arrested. He flees to Switzlerland, and Watson joins him. The criminal mastermind follows Watson and the consulting detective, and the pursuit ends on top of the Reichenbach Falls, leading to a hand-to-hand fight that apparently ends with both Holmes and Moriarty falling to their deaths. Watson does not see this battle to the death, but finds signs that it happened at the cliff edge near the waterfall, as well as a note Moriarty allowed Holmes to write so he could say goodbye.

In the same story, Holmes describes Moriarty's physical appearance to Watson. According to Holmes, Moriarty is extremely tall and thin, clean-shaven, pale, and ascetic-looking. He has a forehead that "domes out in a white curve", deeply sunken eyes, and shoulders that are "rounded from much study". His face protrudes forward and is always slowly oscillating from side to side "in a curiously reptilian fashion".[3] Holmes mentions that when he and the professor first met in person, Moriarty remarked in surprise, "You have less frontal development that I should have expected," indicating that the criminal believes in phrenology.[2]

Moriarty plays a direct role in only one other Holmes story, The Valley of Fear (1914), set before "The Final Problem" but written afterwards. In The Valley of Fear, Holmes attempts to prevent Moriarty's agents from committing a murder. In a scene in which Moriarty is being interviewed by a policeman, a painting by Jean-Baptiste Greuze is described as hanging on the wall; learning this, Holmes mentions the value of another painting by the same artist to show such works could not have been purchased on a professor's salary. The work referred to is La jeune fille à l'agneau;[4] some commentators[5] have described this as a pun by Doyle on a famous Thomas Gainsborough painting, the Portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire,[6] being taken from the Thomas Agnew and Sons art gallery. The gallery believed that Adam Worth was responsible, but was unable to prove the claim.[5]

Holmes mentions Moriarty reminiscently in five other stories: "The Adventure of the Empty House" (the immediate sequel to "The Final Problem"), "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder", "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter", "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client", and "His Last Bow" (the final adventure in Sherlock's canon timeline, taking place years after he has officially retired).

Doctor Watson, even when narrating, never meets Moriarty (only getting distant glimpses of him in "The Final Problem") and relies upon Holmes to relate accounts of the detective's feud with the criminal. Doyle is inconsistent on Watson's familiarity with Moriarty. In "The Final Problem", Watson tells Holmes he has never heard of Moriarty, while in "The Valley of Fear", set earlier on, Watson already knows of him as "the famous scientific criminal".

In "The Empty House", Holmes states that Moriarty had commissioned a powerful air gun from a blind German mechanic surnamed von Herder, which was used by Moriarty's employee/acolyte Colonel Moran. It closely resembled a cane, allowing easy concealment, was capable of firing revolver bullets at long range, and made very little noise when fired, making it ideal for sniping. Moriarty also has a marked preference for organising "accidents". His attempts to kill Holmes include falling masonry and a speeding horse-drawn vehicle. He is also responsible for stage-managing the death of Birdy Edwards, making it appear that he was lost overboard while sailing to South Africa.[7]

Personality[]

Moriarty is highly ruthless, shown by his steadfast vow to Sherlock Holmes that "if you are clever enough to bring destruction upon me, rest assured that I shall do as much to you".[8] Moriarty is categorised by Holmes as an extremely powerful criminal mastermind adept at committing any atrocity to perfection without losing any sleep over it. It is stated in "The Final Problem" that Moriarty does not directly participate in the activities he plans, but only orchestrates the events or provides the plans that will lead to a successful crime. What makes Moriarty so dangerous is his extremely cunning intellect:

He is a man of good birth and excellent education, endowed by nature with a phenomenal mathematical faculty. [...] But the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which, instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers. [...] He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organiser of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city...

— Holmes, "The Final Problem"

Holmes echoes and expounds this sentiment in The Valley of Fear, stating:

The greatest schemer of all time, the organizer of every devilry, the controlling brain of the underworld, a brain which might have made or marred the destiny of nations—that's the man! But so aloof is he from general suspicion, so immune from criticism, so admirable in his management and self-effacement, that for those very words that you have uttered he could hale you to a court and emerge with your year's pension as a solatium for his wounded character. [...] Foulmouthed doctor and slandered professor—such would be your respective roles! That's genius, Watson.

— Holmes, The Valley of Fear

Moriarty respects Holmes's intelligence, stating: "It has been an intellectual treat for me to see the manner in which you [Holmes] have grappled with this case." Nevertheless, he makes numerous attempts upon Holmes's life through his agents. He shows a fiery disposition, becoming enraged when his plans are thwarted, resulting in his being placed "in positive danger of losing my liberty". While personally pursuing Holmes at a train station, he furiously elbows aside passengers, heedless of whether this draws attention to himself.

Doyle's original motive in creating Moriarty was evidently his intention to kill Holmes off.[9] "The Final Problem" was intended to be exactly what its title says; Doyle sought to sweeten the pill by letting Holmes go in a blaze of glory, having rid the world of a criminal so powerful and dangerous that any further task would be trivial in comparison (as Holmes says in the story itself). Eventually, however, public pressure and financial troubles impelled Doyle to bring Holmes back. While Doyle conceded to revealing that Holmes did not die during "The Final Problem" (as Watson mistakenly concludes), he chose not to undo Moriarty's death in a similar fashion. For this reason, the later novel The Valley of Fear features Moriarty as an active villain but is specified to take place before the events of "The Final Problem".[10]

Fictional character biography[]

As established in Doyle's canon, Moriarty first gains recognition at the age of 21 for writing "a treatise upon the Binomial Theorem", which leads to his being awarded the Mathematical Chair at one of England's smaller universities. Moriarty later authors a much respected work titled The Dynamics of an Asteroid. After he becomes the subject of unspecified "dark rumours" in the university town, he is compelled to resign his teaching post and leave the area.[11] He moves to London, where he establishes himself as an "army coach", a private tutor to officers preparing for exams.[3] He becomes a consulting criminal mastermind for various London gangs and criminals (it is uncertain if he was already doing this before leaving his teaching post). When multiple plans of his are hampered or undone by Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty targets the consulting detective.[2]

Multiple pastiches and other works outside of Doyle's stories purport to provide additional information about Moriarty's background. John F. Bowers, a lecturer in mathematics at the University of Leeds, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in 1989 in which he assesses Moriarty's contributions to mathematics and gives a detailed description of Moriarty's background, including a statement that Moriarty was born in Ireland (an idea based on the fact that the surname is Irish in origin).[12][13] The 2005 pastiche novel Sherlock Holmes: The Unauthorized Biography also reports that Moriarty was born in Ireland, and states that he was employed as a professor by Durham University.[14] According to the 2020 audio drama Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason, written by George Mann and Cavan Scott, Moriarty was a professor at Stonyhurst College (where Arthur Conan Doyle was educated and knew two students with the surname Moriarty).[15]

Family[]

The stories give contradictory indications about Moriarty's family. In his first appearance in "The Final Problem" (1893), the villain is referred to only as "Professor Moriarty". Watson mentions no forename but does refer to the name of another family member when he writes of "the recent letters in which Colonel James Moriarty defends the memory of his brother". In "The Adventure of the Empty House" (1903), Holmes refers to Moriarty as "Professor James Moriarty". This is the only time Moriarty is given a first name, and oddly, it is the same as that of his purported brother.[3] In the 1914 novel The Valley of Fear (written after the preceding two stories, but set earlier), Holmes says of Professor Moriarty: "He is unmarried. His younger brother is a station master in the west of England."[16] In Sherlock Holmes: A Drama in Four Acts, an 1899 stage play, of which Doyle was a co-author, the villain is named Professor Robert Moriarty.[17]

Writer Vincent Starrett suggested that Moriarty could have one brother (who is both a colonel and station master) or two brothers (one a colonel and the other a station master); he added that he considered the presence of two siblings more likely, and suggested that all three brothers were named James.[1] Writer Leslie S. Klinger that suggested Professor Moriarty has an older brother named Colonel James Moriarty in addition to an unnamed younger brother. According to Klinger, writer Ian McQueen proposed that Moriarty does not actually have any brothers,[18] while Sherlockian John Bennett Shaw suggested, like Starret, that there are three Moriarty brothers, all named James.[19] The premise that Professor James Moriarty has two brothers also named James was used in the radio series The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and the manga and anime series Moriarty the Patriot.

Adaptations[]

Theatre[]

- In the William Gillette play, Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty was played on Broadway in the original (1899–1900) run by George Wessells (and again in 1905),[20] then by Frank Keenan (1928),[21] John Miltern (1929–30)[22] and Philip Locke, Clive Revill and Alan Sues from 1974–76.[23]

- In the play Sherlock Holmes by Ouida Bergère (wife of actor Basil Rathbone), which ran at the New Century Theatre in New York City for only three performances from 30–31 October 1953, Moriarty was played by Thomas Gomez.[24]

- Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke, who played Holmes and Watson in the Granada Television series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1984–94), reprised their roles for Jeremy Paul's revisionist stage play, The Secret of Sherlock Holmes (1988–89). The only characters in the play are Holmes and Watson, and it highlights many aspects of their relationship from their first meeting to the Reichenbach Falls. In the second half, it is indicated that Moriarty never existed: he was a figment of Holmes' imagination, as the detective needed a worthy enemy as much as he needed a devoted friend like Watson.[25]

Radio[]

- Louis Hector played the villain in numerous episodes of NBC's The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1934-1935).[26]

- Orson Welles played Professor Moriarty opposite Sir John Gielgud's Holmes in the episode "The Final Problem" of the 1954 series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.[27]

- Ralph Truman portrayed Moriarty in the 1955 BBC Home Service adaptation of "The Final Problem".[28]

- In the BBC Radio 4 November 1992 broadcast of The Final Problem and 24 February 1993 broadcast of The Empty House, Moriarty was played by Michael Pennington.[29]

- In the 1999 BBC radio comedy series The Newly Discovered Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty was played by Geoffrey Whitehead.[30]

- In the podcast Hollywood Handbook, Moriarty is played by Hayes Davenport where he is usually fighting the antihero Santaman, played by Sean Clements.[31]

Film[]

- Ernest Maupain portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes (1916).[32]

- Gustav von Seyffertitz portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes (1922).[33]

- Norman McKinnel portrayed Moriarty in The Sleeping Cardinal (1931).[34]

- Ernest Torrence portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes (1932).[35]

- Lyn Harding portrayed Moriarty in The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes (1935) and Silver Blaze (1937).[36]

- George Zucco portrayed Moriarty in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939).[36]

- Lionel Atwill portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942).[36]

- Henry Daniell portrayed Moriarty in The Woman in Green (1945).[37]

- Hans Söhnker portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace (1962).[27]

- Leo McKern portrayed Moriarty in The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes' Smarter Brother (1975).[38]

- Laurence Olivier portrayed Moriarty in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976),[38] based on the 1974 revisionist novel of the same name. In this version he is not the story's villain, but merely a harmless man who becomes an increasingly paranoid victim of Holmes' delusions, brought on by his addiction to cocaine and based on the fact that Moriarty indirectly contributed to the death of Holmes' mother, who was his lover.[39]

- In Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), Anthony Higgins plays Holmes' schoolmaster, Rathe, who turns out to be an evil Egyptian mastermind called "Eh-Tar". During the long credit roll at the end of the film, Eh-Tar is seen walking to an inn and signs the ledger as "Moriarty", indicating that he will become Holmes' archenemy in the future.[40] Higgins later portrayed Holmes in Sherlock Holmes Returns (1993),[41] making him one of only two actors to portray both Holmes and Moriarty on film (Richard Roxburgh being the other; Orson Welles played both Holmes and Moriarty in radio programmes).

- Paul Freeman appeared as Moriarty in Without a Clue (1988); the film revolves around the premise that Dr. Watson (Ben Kingsley), who is the real crime-solving genius, has hired a boozy, out-of-work actor (Michael Caine) to play "Holmes". Moriarty is aware of the deception and refers to "Holmes" as "that imbecile", as opposed to Watson, whom he grudgingly respects.[42]

- Anthony Andrews appeared as Moriarty in Hands of a Murderer (1990).[43]

- In the anime film Case Closed: The Phantom of Baker Street (2002), Professor Moriarty tells Conan that he trained Jack the Ripper when Jack was a street urchin.

- Vincent D'Onofrio appeared as Moriarty in the TV movie Sherlock: Case of Evil (2002).[44]

- In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), the film adaptation of the graphic novel by Alan Moore, Richard Roxburgh portrays the main antagonist named the Phantom, whose true identity was eventually revealed to be Professor James Moriarty.[45] After a battle with Allan Quatermain (Sean Connery), Moriarty manages to inflict a fatal wound on Quatermain when the hunter is distracted saving Tom Sawyer (Shane West) from an invisible man created by Moriarty's scientists, but Sawyer manages to kill Moriarty as he escapes using the shooting skills taught to him by Quatermain.

- In the 2009 film, Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty appears as a shadowy, mysterious villain employing Irene Adler. The role was voiced by the film's dialect coach, Andrew Jack[46] (although director Guy Ritchie refused to reveal his identity).[47] Jared Harris played the role in the 2011 sequel, Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows,[48] as well as redubbing the character's lines from the first film in subsequent home releases and television broadcasts. In the second film, Moriarty and Holmes attend a European Peace Conference held near the Reichenbach Falls which Moriarty seeks to sabotage, and the two plunge down from a balcony overlooking the falls, Holmes being too injured to defeat Moriarty in a straight fight but knowing that Moriarty will go after Watson if he lives. While Holmes is shown to have survived, Moriarty's fate is less certain.

- Jamie Demetriou voiced a pie mascot version of Moriarty in the 2018 animated film Sherlock Gnomes.

- Ralph Fiennes portrayed Moriarty in the 2018 film Holmes & Watson, a comedic take on the Holmes and Watson characters. While the film was criticised, many fans complimented the presence Fiennes created as Moriarty.

Television[]

- John Huston portrayed Moriarty in the made-for-TV movie Sherlock Holmes in New York (1976) opposite Roger Moore's Holmes, attempting to rob the international gold exchange in New York while threatening Irene Adler's son to prevent Holmes from investigating, although Holmes and Watson are able to rescue the son and solve the crime regardless, forcing Moriarty to flee after a last attempt to kidnap Irene's son after Holmes exposes the truth behind the crime and is able to arrange for the rest of Moriarty's American forces to be arrested.[49]

- In the Soviet series of television films The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson (1979–1986) by Igor Maslennikov, Moriarty was played by Viktor Yevgrafov and voiced by Oleg Dahl in the second film of the series, also titled The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson (1980). The film is made of three episodes: "The King of Blackmail" (based on "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton"), "Deadly Fight" (based on "The Final Problem") and "The Tiger Hunt" (based on "The Adventure of the Empty House").[50]

- An anthropomorphic incarnation of Moriarty appeared in the anime series Sherlock Hound (1984–1985), voiced by Chikao Ōtsuka for Japanese and Hamilton Camp for English. During the series, Moriarty is the main antagonist behind every crime in almost each episode. As the characters were depicted as anthropomorphic dogs, Moriarty himself is seen closely resembling a wolf.[51]

- Eric Porter portrayed Moriarty in three episodes of the TV series Sherlock Holmes (1984–1994), starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes: "The Red-Headed League" (1985) "The Final Problem" (1985) and "The Empty House" (1986).[52] The three episodes in question are the last two of the first series, known as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, and the first one of the second series, known as The Return of Sherlock Holmes. Stock footage of Moriarty also appeared as a hallucination in the episode "The Devil's Foot" (1988), also from the second series. In the feature-length episode The Eligible Bachelor (1993), adapted from "The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor", Holmes describes Moriarty as "a giant of evil" and says, "I regret Moriarty's death [because] without him, I have to deal with distressed children, cat-owners—pygmies, pygmies of triviality. You see, Moriarty combined science with evil. Organization with precision. Vision with perception. I know of only one person that he misjudged. Me." The episode is part of the third series, known as The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes.

- Moriarty appeared in two episodes of the animated series BraveStarr (1987–1988), voiced by Jonathan Harris.

- A holodeck simulation of Professor Moriarty, played by actor Daniel Davis, appeared in the Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–1994) episodes "Elementary, Dear Data" (1988) and "Ship in a Bottle" (1993), accidentally achieving an artificial sentience when Geordi La Forge asks the holodeck to create an opponent able to defeat Data (rather than Sherlock Holmes).[53]

- "Elementary My Dear Winston", the third episode for the 1989 season of The Real Ghostbusters (1986–1992), features Holmes, Watson and Moriarty (voiced by , Maurice LaMarche, and Rodger Bumpass, respectively) by way of "belief made manifest": so many people believed in them that they became real. Moriarty now has supernatural powers and employs the Hound of the Baskervilles as his henchman. Holmes and Moriarty are both sucked into the Ghostbusters' storage facility while wrestling, in the same manner as the conclusion of "The Final Problem".

- In the animated series Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century (1999–2001), Moriarty (voiced by Richard Newman) was the villain behind nearly all of the crimes. He had been cloned back to life by a rogue geneticist, requiring Holmes to be "resurrected" as well in order to match him. The body of the original Moriarty was still frozen in ice behind the waterfall that he fell from during his battle with Holmes.[54]

- Moriarty appears as a holographic character in the Futurama (1999–2013) episode "Kif Gets Knocked Up a Notch" (2003), where he comes out of the Holoshed of the Nimbus with Attila the Hun, Jack The Ripper, and Evil (Abraham) Lincoln.

- Jim Moriarty is played by actor Andrew Scott in the modern-day BBC adaptation, Sherlock (2010–present), as a psychopathic "consulting criminal" who develops a murderous obsession with Holmes.[55] He appears behind the scenes for most of the first two seasons, creating a series of apparent suicides and then setting up a sequence of events where Holmes must solve key mysteries before people are blown up by timed bomb vests, culminating in a confrontation in a swimming pool that is cut short by an unexplained phone call that prompts Moriarty to depart to deal with other matters. In the Series 2 finale "The Reichenbach Fall" (2012), he briefly assumes the identity of Richard Brook ("Reicher Bach" in German), creating the illusion that Holmes is behind his crimes and paid him to assume the role of Moriarty. Through this he destroys Holmes' reputation and also threatens his friends in order to drive Holmes to suicide. He himself commits suicide in the climax of the episode, but, at the end of the later episode "His Last Vow" (2014), his face appears on TV screens across the country. Although Holmes spends most of the subsequent special ("The Abominable Bride", 2016) in an elaborate hallucination of a similar case in 1895 to try to determine how Moriarty might have survived, he eventually concludes that Moriarty is genuinely dead, but had planned in advance to have others carry out his plans after his own death. During "The Six Thatchers" (2017), Holmes states his confidence that Moriarty's plans will go into action at some future date, but makes it clear that he will currently act as normal as he is certain that Moriarty's trap will make itself obvious when the time is right. The episode "The Final Problem" reveals that, prior to his death, Moriarty had conspired with the true mastermind of the plot, Sherlock's sister Eurus.

- In the US television series Elementary (2012–present), Moriarty is a composite character with Irene Adler (played by Natalie Dormer). As with Moriarty, she is first mentioned in the 12th episode of the first season ("M", 2013). Holmes tracks an apparent serial killer who uses the name "M"; upon his capture, he is discovered to be Sebastian Moran, Moriarty's henchman, whose seemingly random murders were actually assassinations carried out for his employer, whom he claims to have never met. In the season finale, "Irene Adler" is revealed to be an alias created by Moriarty in order to get close to Holmes and observe him (a male voice who spoke to Holmes as "Moriarty" over the telephone is revealed to be a hired actor). The episode "We Are Everyone" (2013) reveals her true name as Jamie Moriarty and she continues to write letters to Holmes from prison.[56] She briefly escapes prison to assist in an investigation of a kidnapping of a girl who is revealed to be her daughter, abducted by the man who acted as Moriarty in past conversations, but willingly returns to custody after her daughter is safe. Despite being in prison, she later arranges for a ruthless crime boss to be assassinated after the woman attempts to kill Holmes' assistant Joan Watson, sending her a letter to confirm her involvement. In the last episodes of Season Four, Holmes and Watson meet the father of Moriarty's child, who has taken over her organization after her incarceration. He is arrested thanks to the actions of Sherlock's father Morland, who takes over the operation in order to dismantle it from within and ensure that none of its assets can be used against his son. By the time of the final episode of the series, Morland is dead, Moriarty's organisation basically disbanded, and Moriarty herself is presumed by the government to be dead, although Holmes expresses doubts about this even after attending her funeral.

- In the Russian-produced Sherlock Holmes (2013) series by Andrey Kavun, Moriarty was played by actor Alexey Gorbunov. Moriarty is a mathematics professor who attempts to assassinate the Queen. He appeared as the head of a London-wide criminal network called "The Cabmen Gang".[57]

- In the NHK puppetry Sherlock Holmes (2014–present), Moriarty is the tall and blond deputy headmaster of Beeton School where Holmes and Watson study and live, and has a face with two different aspects: one of which looks calm but the other looks severe. Though he always behaves gentlemanly, he is strict with pupils, especially Holmes, who behaves at his own pace.[58] He usually calls a pupil by his/her given name and surname; for example, he calls Watson "John Hamish Watson".[59] He is voiced by Masashi Ebara.[58]

- Moriarty is a recurring character in season 2 of The Librarians (2014–2018), where is he is played by David S. Lee. Here, Moriarty has been brought to life by Prospero of William Shakespeare's The Tempest, and is forced to serve as his strategist. Though he maintains his loyalty to Prospero throughout the season, he eventually betrays him in the final episode, only to be banished back to his story as punishment. At the last second, he reveals that the only way to beat Prospero is to destroy his staff.

- James Moriarty is a recurring character in Case File nº221: Kabukicho. He is voiced by: Seiichirō Yamashita (Japanese); Justin Briner (English).

- In HBO Asia/Hulu's re-imagining Miss Sherlock, Moriarty is first mentioned in episode six under the name Akira Moriwaki, and is believed to be behind the events of most of the series. Episode seven reveals Moriwaki to be Wato's (the Watson analogue) middle-aged female psychiatrist, Dr. Mariko Irikawa.

- Moriarty is the main protagonist of the anime series Moriarty the Patriot, which was adapted from the manga series of the same name.

Literature[]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2018) |

- In Nicholas Meyer's 1974 revisionist novel, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Moriarty is portrayed as Holmes' childhood mathematics tutor, a whining little man with a guilty secret. He is incensed to hear that Holmes, apparently under the influence of cocaine, has depicted him as a criminal mastermind. Due to Holmes' worsening condition, Moriarty threatens to tell the authorities about Holmes' addiction. Dr. Watson seeks the help of Sigmund Freud, who uncovers the truth behind Holmes' perception of "the Napoleon of Crime". This is one of many works to seize on the fact that Moriarty never actually shows his face in the Holmes canon. The novel was made into a 1976 film and starred Laurence Olivier as a very different sort of Professor Moriarty.

- John Gardner has written three novels featuring the arch-villain: The Return of Moriarty (1974), in which the Professor, like Holmes, is shown to have survived the meeting at the Reichenbach, The Revenge of Moriarty (1975) and Moriarty (released posthumously in 2008 after the author's death in 2007). In these novels, Moriarty is depicted as a Victorian-era Al Capone or Don Corleone, who single-handedly controls London's organised crime structure. "The Professor" is not really Moriarty, but Moriarty's younger brother, also named James, and as brilliant as his older brother, whom he impersonates, disgraces and murders, later stealing the deceased's identity.

- Kim Newman used Moriarty as a minor character in the first volume of his Anno Dracula (1992) series; he claims to have given up his criminal interests, in the face of Count Dracula's increasing domination of London, and become a vampire in order to have infinite time to pursue his mathematical researches. Newman later wrote a series of short stories about Moriarty, narrated Watson-style by Colonel Moran, in which Moriarty interacts with many of his fictional contemporaries. They have been collected in Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles (2011). One of the stories, "The Red Planet League", first appeared in Gaslight Grimoire. Another story, "The Adventure of the Greek Invertebrate" (a play on "The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter", which introduced Sherlock Holmes' brother Mycroft), features Professor Moriarty's two brothers, also named James, the colonel and the station master, and offers an explanation for the lack of variety in their forenames. The last story, "The Problem of the Final Adventure", is a revisionist retelling of "The Adventure of the Final Problem" from the other side.

- Moriarty appears in a short story by Donald Serrell Thomas, in his collection The Secret Cases of Sherlock Holmes (1997), as the mastermind of a blackmail plot involving the alleged bigamy of Prince George. His younger brother, Col. James Moriarty, appears as the antagonist of another short story in Thomas' The Execution of Sherlock Holmes (2007).

- Michael Kurland has written a series of five novels (The Infernal Device, Death by Gaslight, The Great Game, The Empress of India, and Who Thinks Evil) and four short stories featuring Moriarty.

- Moriarty appears in Alan Moore's comic book series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999–present). Recruited from university by British Intelligence, he supposedly set up his criminal empire as part of an undercover operation to monitor crime in London which got out of hand, to the point where the 'cover' became more real to Moriarty than his role in British Intelligence. Having survived the encounter with Holmes, he went on to become head of British Intelligence under the code-name "M" but still maintained his criminal interests. He instigated the creation of the League as a covert ops unit with plausible deniability and used them to recover an anti-gravity mineral called Cavorite which had been stolen by his crimelord rival the Doctor. He used the Cavorite to bomb the East End of London in an attempt to destroy the Doctor but was thwarted by the League which had uncovered the double-cross. Following his supposed death (indicated, but not clearly portrayed, as he "falls" into the sky while clutching the Cavorite), he was ironically succeeded as "M" by Mycroft Holmes, Sherlock's older brother. In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, it is suggested that Jack Kerouac's Dean Moriarty (from On the Road) is his great-grandson, and the rivalry between the two criminals is continued by the fact that the Doctor's great-grandson is Kerouac's other creation, Doctor Sax. In the third volume, set more than six decades later, Mina Murray comes across his carcass, still holding on to the Cavorite, inside a block of ice floating through space.

- In The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes (1999), set during Holmes' three-year fake "death", Holmes encounters Moriarty during his trip in Tibet, where he learns that Moriarty is actually "the Dark One", a former Tibetan mystic possessing great psychic powers who lost his memories in an attack on the Dalai Lama, only for his near-death experience on the Reichenbach Falls to restore his memory, albeit leaving him horribly crippled and disfigured by his injuries. He attempts to acquire a legendary crystal that would allow him to wield even greater power, but, although Moriarty acquires the crystal, boosting his powers and healing his injuries, he is defeated when it is revealed that Holmes is partly possessed by the spirit of the Dark One's old rival. Sharing the spirit of a former llama allows Holmes to wield similar powers to Moriarty's, utilizing these mental powers to delay his old enemy long enough for Holmes' ally, Huree Chunder Mockerjee, to knock the crystal away from Moriarty and into Holmes' hands, giving Holmes the power to turn Moriarty's own abilities against him, vaporising Moriarty's body and destroying him once and for all.

- In Neil Gaiman's short story "A Study in Emerald" (2003), the Moriarty and Holmes of an alternate history reverse roles. Moriarty (who, although never named as such in the story, is identified as the author of Dynamics of an Asteroid) is hired to investigate a murder. The murder has apparently been carried out by Sherlock Holmes (who signs his name Rache, an allusion to Doyle's first novel starring Holmes and Watson, A Study in Scarlet, in which "Rache"—German for "revenge"—is found written above the body of a murder victim) and Dr. Watson. The story is narrated by Colonel Sebastian Moran, given the rank of Major (Ret.) by Gaiman.

- In a 2006 comic book story featuring Lee Falk's The Phantom, the 19th Phantom has to fight Moriarty; the climax of the story features the Phantom and Moriarty falling down a waterfall in the Bangalla jungle. At the end of the story, Moriarty is shown to be alive, as he returns to London to find "a detective named Sherlock Holmes".

- In the comic series Victorian Undead (2010), Holmes and Watson must face a 'reborn' Moriary as he unleashes a zombie plague on London, having survived his own death via a modified zombie formula that allows Moriarty to retain his intellect despite his deathly state.

- In Paco Ignacio Taibo II's "The Return of the Tigers of Malaysia" (2010), Dr James Moriarty appears as the mastermind behind the attacks on Sandokan and his friend Yanez.

- In Anthony Horowitz' 2011 novel The House of Silk, a chapter is dedicated to Watson's meeting with a secretive criminal mastermind. This character is not definitively identified, however it is heavily implied that he is Moriarty. Watson later states that he believes this to be the case, and in an appendix Horowitz states the identity of the character outright. Moriarty also appears as a corpse in Moriarty, the 2014 sequel to this novel, in which Pinkerton detective Frederick Chase is investigating the events that took place at the Reichenbach Falls.

- In The Thinking Engine (2015) by James Lovegrove, set in 1895—specifically at the same time as the events of "The Adventure of the Three Students"—Holmes is called to challenge the Thinking Engine, an early computer that is seemingly capable of solving crimes using the same deductive abilities as Holmes himself. As the novel unfolds, Holmes realizes that every case the Engine has been called on to solve was committed by a perpetrator who had to be assisted by someone else to come up with such an intellectual scheme. In the final confrontation, Holmes and his allies realize that the Thinking Engine is actually a hollow construct with Moriarty inside it; he survived the confrontation at the Reichenbach Falls as he was wearing a specially designed body armour that protected his vital organs, although his limbs were so injured that his legs and one arm have been amputated and he can still barely speak on his own due to damage to his larynx. With his deception exposed, Moriarty apparently dies due to complications of the drugs being used to medicate his injuries, although it is strongly implied that Holmes gave him a deliberate overdose to prevent the risk of a trial allowing Moriarty to escape again.

- In Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell (2016) by Paul Kane, it is revealed that Moriarty was able to escape his demise by using an incantation to transfer himself into the realm of the Cenobites, where he is transformed into the 'Engineer' of the Cenobites, intending to mount a new assault on Earth. Holmes is able to make a deal with the master Cenobites to transform himself into a Cenobite to oppose Moriarty's forces, the final confrontation seeing Moriarty destroyed once again, while Watson is able to make his own deal to restore Holmes to normal.

- In The Cthulhu Casebooks by James Lovegrove, presenting an alternate version of Holmes' cases where he and Watson regularly faced the Great Old Ones of H. P. Lovecraft's work, Moriarty is the antagonist of the first novel, Sherlock Holmes and the Shadwell Shadows (2016), set in 1881, where he attempts various sacrifices to win the aid of the old god Nyarlathotep, but is drawn in by his would-be god when he attempts to sacrifice Holmes, Watson, Mycroft and Gregson, although Holmes speculates that he has some plan to return.

- In the sequel, Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities (2017), Holmes and Watson learn in 1896 that Moriarty's willing sacrifice of himself to Nyarlathotep gave him the strength of will to consume his would-be god's power for himself, leading some of the other Outer Gods against the Old Ones in preparation for an assault on Earth due to his greater ambition and drive. Holmes and Watson are able to defeat Moriarty's current assault by destroying his human agent, but they are each aware that Moriarty will return.

- In the conclusion of the trilogy, Sherlock Holmes and the Sussex Sea-Devils, set in 1910, after killing Mycroft Holmes and various other old allies of Sherlock with his mortal agents, Moriarty captures Holmes and Watson with the intention of taking them to witness his destruction of Cthulhu's physical form as his Outer God forces destroy Cthulhu's mind on the higher planes, which he believes will allow him to kill Cthulhu and ensure his own dominance. However, Holmes had secretly made a deal with Cthulhu years ago to maintain his own vitality while hunting Cthulhu's enemies on this plane, and when Holmes grants permission for Cthulhu to take back what was given, it gives Cthulhu such a power boost that he recovers from the injuries inflicted by Moriarty's efforts, with the two last shown engaging in a physical struggle as they ascend into the higher planes.

- In the manga series Moriarty the Patriot written by Ryōsuke Takeuchi and illustrated by Hikaru Miyoshi, the story follows a young Moriarty and his two brothers, expanding on their motives for following a path of crime.

Video games[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2014) |

- In the computer adventure Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened (2007), Holmes encounters Moriarty locked in a Switzerland mental hospital in 1895 (four years after "The Final Problem"), where the Professor has suffered severe brain injuries from the Falls. Not recognising Holmes in disguise, Moriarty is tricked into thinking his nemesis is in the hospital lobby, and charges from his cell in a frenzy, giving Holmes a diversion so he may investigate the asylum's secrets further.

- In Sherlock Holmes Versus Arsène Lupin, or Sherlock Holmes: Nemesis, there has been no word of any mental recovery or escape attempts by Moriarty. Holmes remarks to Watson, "If there had, we would be on the way to Switzerland already."

- Moriarty returns in The Testament of Sherlock Holmes (2012), as the main antagonist who tries to frame Holmes and create anarchy in response for being tricked by Holmes in the Black Edelweiss Institute in Switzerland. Before he died, Moriarty asked Holmes to take care her daughter Katelyn.

- In Sherlock Holmes: The Devil's Daughter (2016), Moriarty's death continues to haunt Holmes due to the fact that Sherlock adopted Moriarty's daughter Katelyn and is living in fear of her discovering the truth about her biological father and following in his footsteps. After Kate is kidnapped Holmes discovers Moriarty's crypt and a message he left for Kate where it's revealed Moriarty anticipated both his death and Kate's adoption, he attempts to convince her to turn against Holmes and continue his work.

- In the mobile game Fate/Grand Order (2015), Moriarty is an Archer class Servant and the antagonist of the Shinjuku chapter. His alias is Archer of Shinjuku.

- In the massive-multiplayer role-playing online game Wizard101 (2008) there is a character based on Moriarty, named "Meowiarty".

- Although he doesn't properly make an appearance in it, the videogame The Great Ace Attorney 2: Resolve (2017) features a serial killer named "The Professor", in an allusion to Moriarty.

Actors who have played Moriarty[]

Radio and audio dramas[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louis Hector | The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Missing Leonardo Da Vinci"[60] | 1932 | Radio (NBC Blue Network) |

| Charles Bryant | Lux Radio Theatre – "Sherlock Holmes"[61] | 1935 | Radio adaptation of the play (NBC) |

| Eustace Wyatt | The Mercury Theatre on the Air – "Sherlock Holmes" | 1938 | Radio adaptation of the play (CBS) |

| Joseph Kearns | The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Singular Case of the Paradol Chamber"[62] | 1945 | Radio (Mutual) |

| Denis Green | The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The April Fool's Adventure"[63] | 1946 | |

| Robert Dryden | The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Guest in the Coffin"[64] | 1949 | |

| Frederick Valk | Sherlock Holmes[65] | 1953 | Radio adaptation of the play (BBC) |

| Orson Welles | The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Final Problem"[66] | 1954 | BBC Light Programme |

| Ralph Truman | Sherlock Holmes – "The Final Problem"[67] | 1955 | BBC Home Service |

| Felix Felton | Sherlock Holmes – "The Final Problem"[68] | 1957 | BBC Home Service |

| Rolf Lefebvre | Sherlock Holmes – "The Final Problem"[69] | 1967 | BBC Light Programme |

| Michael Pennington | BBC Radio Sherlock Holmes – "The Final Problem", "The Empty House" | 1992 | BBC Radio 4 |

| Ronald Pickup | BBC Radio Sherlock Holmes – The Valley of Fear[70] | 1997 | BBC Radio 4 |

| David King | The Seven-Per-Cent Solution | 1993 | BBC radio dramatisation of the novel |

| Geoffrey Whitehead | The Newly Discovered Casebook of Sherlock Holmes | 1999 | BBC Radio 2 |

| Nolan Palmer | The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Moriarty Resurrection"[71] | 2006 | Radio (Imagination Theatre) |

| Richard Ziman | The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – "The Return of Sherlock Holmes"[72] | 2009 | |

| Alan Cox | Sherlock Holmes: The Final Problem/The Empty House[73] | 2011 | Audio drama (Big Finish Productions) |

| Gerard McDermott | Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason[74] | 2020 | Audio drama (Audible Original) |

Stage plays[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Wessells | Sherlock Holmes | 1899 | Broadway (American) |

| Frank Keenan | Sherlock Holmes | 1928 | Broadway (American) |

| Thomas Gomez | "Sherlock Holmes" by Ouida Bergère[75] | 1953 | Broadway (American) |

| Martin Gabel | Baker Street | 1965 | Stage musical (Broadway) |

| Terry Williams | Sherlock Holmes: The Musical | 1988 | Stage musical (Exeter, England) |

Television and DTV films[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Huston | Sherlock Holmes in New York | 1976 | Television film (American) |

| Viktor Yevgrafov | The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson | 1980 | Television film (USSR) |

| Anthony Andrews | Hands of a Murderer | 1990 | Television film (British) |

| Vincent D'Onofrio | Sherlock: Case of Evil | 2002 | Television film (American) |

| Steve Powell | Case Closed: The Phantom of Baker Street | 2010 | Japanese anime film (English dub, released on DVD) |

| Malcolm McDowell | Tom and Jerry Meet Sherlock Holmes | 2010 | Animated direct-to-DVD film (American) |

Television series[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colin Jeavons | The Baker Street Boys – "The Adventure of the Winged Scarab" Parts 1 and 2 | 1983 | TV episodes (British) |

| Chikao Ōtsuka | Sherlock Hound | 1984–1985 | TV animated series (Italian-Japanese) (Japanese version) |

| Hamilton Camp | Sherlock Hound | 1984–1985 | TV animated series (Italian-Japanese) (English dub) |

| Mauro Bosco | Sherlock Hound | 1984–1985 | TV animated series (Italian-Japanese) (Italian dub) |

| Eric Porter | Sherlock Holmes | 1985 | TV series (British) |

| Daniel Davis | Star Trek: The Next Generation – "Elementary, Dear Data" and "Ship in a Bottle" | 1988, 1993 | TV episodes (American) |

| John Colicos | Alfred Hitchcock Presents – "My Dear Watson" | 1989 | TV episode (American) |

| Richard Newman | Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century | 1999–2001 | TV series (British-American) |

| Andrew Scott | Sherlock | 2010–2017 | TV series (British) |

| Natalie Dormer | Elementary | 2013–2015 | TV series (American) |

| Alexey Gorbunov | Sherlock Holmes | 2013 | TV series (Russian) |

| Masashi Ebara | Sherlock Holmes | 2014–2015 | TV series (Japanese) |

| David S. Lee | The Librarians | 2015 | TV series (American) |

| Seiichirō Yamashita | Case File nº221: Kabukicho | 2019–2020 | TV anime series (Japanese) (Japanese version) |

| Justin Briner | Case File nº221: Kabukicho | 2019–2020 | TV anime series (Japanese) (English dub) |

| Sōma Saitō | Moriarty the Patriot | 2020–2021 | TV anime series (Japanese) |

| Shizuka Ishigami | Moriarty the Patriot | 2020–2021 | TV anime series (Japanese) (Younger version) |

Theatrical films[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ernest Maupain | Sherlock Holmes | 1916 | First silent film adaptation of the stage play (American) |

| Booth Conway | The Valley of Fear | Silent film (British) | |

| Gustav von Seyffertitz | Sherlock Holmes | 1922 | Silent film adaptation of the stage play (American) |

| Percy Standing | The Final Problem | 1923 | Stoll series short silent film (British) |

| Harry T. Morey | The Return of Sherlock Holmes | 1929 | American film |

| Norman McKinnel | The Sleeping Cardinal | 1931 | 1931–1937 film series (British) |

| Ernest Torrence | Sherlock Holmes | 1932 | First sound adaptation of the stage play (American) |

| Lyn Harding | The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes | 1935 | 1931–1937 film series (British) |

| Silver Blaze | 1937 | ||

| George Zucco | The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes | 1939 | 1939–1946 film series (American) |

| Lionel Atwill | Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon | 1942 | |

| Henry Daniell | The Woman in Green | 1945 | |

| Hans Söhnker | Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace | 1962 | West German-French-Italian film |

| Leo McKern | The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes' Smarter Brother | 1975 | American film |

| Laurence Olivier | The Seven-Per-Cent Solution | 1976 | American film |

| Anthony Higgins | Young Sherlock Holmes | 1985 | American film |

| Paul Freeman | Without a Clue | 1988 | American film |

| Kiyoshi Kobayashi | Case Closed: The Phantom of Baker Street | 2002 | Japanese anime film (Japanese version) |

| Richard Roxburgh | The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen | 2003 | American film |

| Jared Harris | Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows | 2011 | British-American film |

| Ralph Fiennes | Holmes & Watson | 2018 | American film |

Video games[]

| Name | Title | Date | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger L. Jackson | The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: The Case of the Rose Tattoo[76][77] | 1996 | Voice only; digitized sprites based on a different actor |

| George Gregg | The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: The Case of the Rose Tattoo[77] | 1996 | Digitized-sprite actor |

| Unknown actor | The Testament of Sherlock Holmes | 2012 | Sherlock Holmes series; voice role |

| Unknown actor | Sherlock Holmes: The Devil's Daughter | 2016 | |

| Takaya Hashi | Fate/Grand Order (Limited event character)[78][79] | 2017 | Mobile game; voice role (Japanese) |

Real-world role models[]

"Moriarty" is an ancient Irish name[80] as is Moran, the surname of Moriarty's henchman, Sebastian Moran.[81][82] Doyle himself was of Irish Catholic descent, educated at Stonyhurst College, although he abandoned his family's religious tradition, neither marrying nor raising his children in the Catholic faith, nor cleaving to any politics that his ethnic background might presuppose. Doyle is known to have used his experiences at Stonyhurst as inspiration for details of the Holmes series; among his contemporaries at the school were two boys surnamed Moriarty.[83]

ln addition to the master criminal Adam Worth, there has been much speculation among astronomers and Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts that Doyle based his fictional character Moriarty on the Canadian-American astronomer Simon Newcomb.[84] Newcomb was revered as a multitalented genius, with a special mastery of mathematics, and he had become internationally famous in the years before Doyle began writing his stories. More to the point, Newcomb had earned a reputation for spite and malice, apparently seeking to destroy the careers and reputations of rival scientists.[85]

Moriarty may have been inspired in part by two real-world mathematicians. If the characterisations of Moriarty's academic papers are reversed, they describe real mathematical events. Carl Friedrich Gauss wrote a famous paper on the dynamics of an asteroid[86] in his early 20s, and was appointed to a chair partly on the strength of this result. Srinivasa Ramanujan wrote about generalisations of the binomial theorem,[87] and earned a reputation as a genius by writing articles that confounded the best extant mathematicians.[88] Gauss's story was well known in Doyle's time, and Ramanujan's story unfolded at Cambridge from early 1913 to mid 1914;[89] The Valley of Fear, which contains the comment about maths so abstruse that no one could criticise it, was published in September 1914. Irish mathematician Des MacHale has suggested George Boole may have been a model for Moriarty.[90][91]

Jane Stanford, in That Irishman, suggests that Doyle borrowed some of the traits and background of the Fenian John O'Connor Power for his portrayal of Moriarty.[92] In Moriarty Unmasked: Conan Doyle and an Anglo-Irish Quarrel, 2017, Stanford explores Doyle's relationship with the Irish literary and political community in London. She suggests that Moriarty, Ireland's Napoleon, represents the Fenian threat at the heart of the British Empire. O'Connor, 2018, Power studied at St Jarlath's Diocesan College in Tuam, County Galway.[93] In his third and last year he was Professor of Humanities. As an ex-professor, the Fenian leader successfully made a bid for a Westminster seat in County Mayo.[94]

It is averred that surviving Jesuit priests at the preparatory school Hodder Place, Stonyhurst, instantly recognised the physical description of Moriarty as that of the Rev. Thomas Kay, SJ, Prefect of Discipline, under whose authority Doyle fell as a wayward pupil.[95] According to this hypothesis, Doyle as a private joke has Inspector MacDonald describe Moriarty: "He'd have made a grand meenister with his thin face and grey hair and his solemn-like way of talking."[96]

The model which Doyle himself cited (through Sherlock Holmes) in The Valley of Fear is the London arch-criminal of the 18th century, Jonathan Wild. He mentions this when seeking to compare Moriarty to a real-world character that Inspector Alec MacDonald might know, but it is in vain as MacDonald is not so well read as Holmes.

Legacy[]

T. S. Eliot's character Macavity the Mystery Cat is based on Moriarty.[97]

A Sherlockian society was formed by noted Sherlockian John Bennett Shaw[98] called "The Brothers Three of Moriarty", in honor of Professor Moriarty and his two brothers.[99] The group held annual dinners in Moriarty, New Mexico.[99]

Depictions[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (October 2020) |

Moriarty has been depicted in theater plays, radio broadcasts, films, television series, video games, both manga and anime (Moriarty the Patriot), and various forms of literature.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Starrett, Vincent (2016). 221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes (Reprinted ed.). Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78720-133-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005). p. xxxv. ISBN 0-393-05916-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cawthorne, Nigel (201). A Brief History of Sherlock Holmes. Robinson. pp. 216–220. ISBN 978-0-7624-4408-3.

- ^ "Girl With A Lamb".

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Mortimer (24 August 1997). "To Catch a Thief". The New York Times.. A review of THE NAPOLEON OF CRIME — The Life and Times of Adam Worth, Master Thief by Ben Macintyre.

- ^ "A portrait of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire by Thomas Gainsborough".

- ^ Epilogue, The Valley of Fear.

- ^ Doyle, Conan (1894). "The Adventure of the Final Problem". McClure's Magazine. Vol. 2. Astor Place, New York: J. J. Little and Co. p. 104. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Stashower, Daniel (1999). Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. New York: Holt. p. 149. ISBN 978-0805050745.

- ^ Miller, Ron. "Case Book: Doyle vs. Holmes". PBS.

- ^ Smith, Daniel (2014) [2009]. The Sherlock Holmes Companion: An Elementary Guide (Updated ed.). London: Aurum Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-84513-458-7.

- ^ Bowers, John F. (23 December 1989). "James Moriarty: a forgotten mathematician". New Scientist. pp. 17–19.

- ^ Arbesman, Samuel (2013). The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date. Penguin. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781591846512.

- ^ Rennison, Nick (1 December 2007). Sherlock Holmes: The Unauthorized Biography. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9781555848736.

- ^ Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason (16 March 2020). Audible Original Drama (audiobook). "Chapter 7."

- ^ Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Sherlock Holmes: The Complete Novels and Stories. Volume 2. Random House. p. 175.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Sherlock Holmes, A Drama in Four Acts. ACT II".

- ^ Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume II (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005). p. 811. ISBN 0-393-05916-2.

- ^ Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume III (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006). pp. 652–653. ISBN 0-393-05800-X.

- ^ DeWaal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. pp. 368, 370. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ DeWaal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 371. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ DeWaal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 372. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ Conan Doyle, Sir Arthur; Gilette, William (1976). Sherlock Holmes: A Comedy in Two Acts. Samuel French, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 9780573616068.

- ^ "Basil Rathbone: Master of Stage and Screen - Sherlock Holmes".

- ^ "The Secret of Sherlock Holmes Play". Kli.freeshell.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Pitts, Michael R. (1991). Famous Movie Detectives II. Scarecrow Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780810823457.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 137. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ DeWaal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 385. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ "The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes". Michael Pennington. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Geoffrey Whitehead". The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "The Santaman Saga". Earwolf Media. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 130. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 131. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 132. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 133. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 134. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 135. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 139. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 127. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 231. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 105. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. pp. 224–226. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 57. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Gates, Anita (25 October 2002). "TV WEEKEND; Young Sherlock, Before the Cap and Pipe". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Kelly, Kathleen Coyne; Pugh, Tison (2009). Queer Movie Medievalisms. Ashgate Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 9780754675921.

- ^ "Career | Andrew Jack". andrewjack.com.

- ^ Rich, Katey (28 December 2009). "Is Brad Pitt In Sherlock Holmes After All?". Cinema Blend. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (23 October 2011). "Warner Bros Ready For 'Sherlock Holmes 3'". Deadline. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. pp. 161–163. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. pp. 108–109. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ "Sherlock Hound". Nausicaa.net. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1984): The Red Headed League".

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. pp. 201–202. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. pp. 163–165. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- ^ Rampton, James (15 November 2013). "'Sherlock has changed my whole career': Andrew Scott interview". The Independent. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Gelman, Vlada (1 January 2014). "Elementary Preview: Moriarty Returns With a 'Big Secret'… and a Joan Obsession?". TVLine.com. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Aleksei Gorbunov". The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shinjiro Okazaki and Kenichi Fujita (ed.), "シャーロックホームズ冒険ファンブック Shārokku Hōmuzu Bōken Fan Bukku", Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2014, p. 13

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes" production team (Ed.), "NHK シャーロックホームズ推理ブック Mystery quiz book of Sherlock Holmes", Tokyo:Shufu to seikatsu sha, 2014, p. 57

- ^ Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 42. ISBN 978-1629335070.

- ^ Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 65. ISBN 978-1629335070.

- ^ Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 160. ISBN 978-1629335070.

- ^ Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 196. ISBN 978-1629335070.

- ^ Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 269. ISBN 978-1629335070.

- ^ De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 383. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 137. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 385. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 386. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 392. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- ^ Coules, Bert. "The Valley of Fear". The BBC audio complete Sherlock Holmes. Retrieved 8 July 2020. (The "narrator" is Moriarty.)

- ^ Elliott, Matthew J. (2012). "The Moriarty Resurrection". Sherlock Holmes on the Air. MX Publishing. ISBN 9781780921051.

- ^ "The Return of Sherlock Holmes". Imagination Theatre. 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020. (End credits.)

- ^ "2.1. Sherlock Holmes: The Final Problem/The Empty House". Big Finish. 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason: An Audible Original Drama". Amazon. 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020. (End credits.)

- ^ Eyles, Alan (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. pp. 103. ISBN 0-06-015620-1.

- ^ "The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: The Case of the Rose Tattoo". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: Case of the Rose Tattoo (DOS)". MobyGames. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Green, Scott (30 July 2017). "Sherlock Holmes Tries To Solve The Case Of "Fate/Grand Order" Gacha In Latest Event Summoning". Crunchyroll. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Takaya Hashi". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Daniel Jones; A.C. Gimson (1977). Everyman's English Pronouncing Dictionary (14 ed.). London, UK: J.M. Dent & Sons.

- ^ Moran genealogy site; accessed 28 June 2014.

- ^ Moran profile, irishgathering.ie; accessed 28 June 2014.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Arthur Conan Doyle". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008.

- ^ Schaefer, B. E., 1993, Sherlock Holmes and some astronomical connections, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, vol 103, no. 1, pp. 30–34. For a summary of this point, see this New Scientist article, also from 1993.

- ^ For example, see Newcomb's animosity to the career and works of Charles Peirce.

- ^ Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1809). Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium. Hamburg, Germany: Friedrich Perthes and I.H. Besser., as described in Donald Teets, Karen Whitehead, 1999 "The Discovery of Ceres: How Gauss Became Famous", Mathematics Magazine, vol 72, no 2 (April 1999), pp. 83–93

- ^ "Ramanujan Psi Sum". Mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Kanigel, R. (1991). The man who knew infinity: A life of the genius Ramanujan. Scribner. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-671-75061-9.

- ^ See, for example, the book by Kanigel, The Man Who Knew Infinity

- ^ MacHale, Desmond (1995). "George Boole and Sherlock Holmes". The Legacy of George Boole. Cork, Ireland.

- ^ Lynch, Peter (15 November 2018). "Could Sherlock Holmes's true nemesis have been a mathematician?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Stanford, Jane (2011). That Irishman: The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power. Dublin: The History Press, Ireland. pp. 30, 124–27. ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1.

- ^ Sherlock Holmes' Irish Nemesis, Library Corner, Tuam Herald, 28 February 2018.

- ^ Moriarty Unmasked, p.28.

- ^ "Letter from Stonyhurst achivist about Doyle's experience there" (PDF).

- ^ The Valley of Fear, The Oxford Sherlock Holmes, p. 181

- ^ Dundas, Zach (2015). The Great Detective. Mariner Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-544-70521-0.

- ^ Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. pp. 405–406. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

External links[]

- The Final Problem

- The Valley of Fear

- Sherlock Holmes Public Library

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Professor Moriarty", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- America's Best Comics characters

- Crime film characters

- Literary characters introduced in 1893

- Fictional crime bosses

- Fictional gentleman thieves

- Fictional mass murderers

- Fictional mathematicians

- Fictional professors

- Fictional scientists

- Sherlock Holmes characters

- Fictional British people

- Fictional English people

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in television

- Male literary villains

- Male film villains