Young Sherlock Holmes

| Young Sherlock Holmes | |

|---|---|

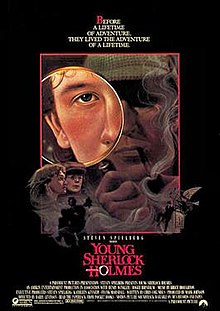

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barry Levinson |

| Screenplay by | Chris Columbus |

| Based on | Characters by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| Produced by | Mark Johnson Henry Winkler Roger Birnbaum |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Stephen Goldblatt |

| Edited by | Stu Linder |

| Music by | Bruce Broughton |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million |

| Box office | $19.7 million |

Young Sherlock Holmes (also known with the title card name of "Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear") is a 1985 American mystery adventure film directed by Barry Levinson and written by Chris Columbus, based on the characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The film depicts a young Sherlock Holmes and John Watson meeting and solving a mystery together at a boarding school.[1]

Plot[]

This section's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (May 2021) |

The mature Dr. John Watson narrates the film, which is full of allusions to Holmesian lore, from his first violin lessons to Waxflatters’ cry of "Elementary!" to the acquisition of a deerstalker.

A younger Watson transfers from his school in the country to London’s Brompton Academy, where Sherlock Holmes befriends him immediately. Holmes’ mentors there include Rupert Waxflatter, an eccentric retired professor to whom the school has given a large attic space for his inventions, which include a flying machine.

Holmes and Waxflatter's niece, Elizabeth, are in love.

Elsewhere in the city, a hooded figure with a blowgun shoots two men with thorns that induce nightmarish hallucinations, causing their apparent suicides. Holmes brings his suspicions of foul play to Scotland Yard detective Lestrade—who has been teaching Holmes about detection—but is rebuffed.

After Dudley, a school rival, frames him for misconduct, Holmes is expelled. He has one last bout with Professor Rathe, the fencing instructor, who constantly warns Holmes about the distractions of emotion. While Holmes says goodbye to Watson, Waxflatter is shot with a thorn and stabs himself. Dying, he whispers the word "Eh-tar" to Holmes. The narrator observes that he only saw Holmes cry twice, the first time being at Waxflatter’s funeral.

Holmes, Watson and Elizabeth secretly investigate the murders, uncovering the existence of Rame Tep, an ancient Egyptian cult of Osiris worshippers. The trio track the cult to a London warehouse and a secret underground pyramid, where they interrupt the sacrifice of a young girl. The Rame Tep pursue them and wound them with thorns, but they survive the hallucinations: Elizabeth imagines the living dead are attacking her and that she is being buried alive by her uncle; Watson imagines that he is being force-fed by sentient pastries; and Holmes imagines that his father is harshly reprimanding him for revealing something embarrassing to his mother, before imaging that a real Eh-Tar assassin trying to kill him is still the image of his father. Lestrade reprimands the young sleuths and dismissing Holmes' deductions. Holmes leaves several poison thorns for analysis, with which Lestrade accidentally pricks his finger.

Back in Waxflatter's loft, Holmes and Watson find a drawing of the three victims and a fourth man, Chester Cragwitch, who is still alive. When Professor Rathe and Mrs. Dribb discover them, they threaten Holmes with prison, tell Watson he must leave in the morning, and inform Elizabeth her uncle’s lab will be cleared out, despite Holmes' protests. That night, while Elizabeth heads to Waxflatter's loft to salvage his work, Holmes and Watson call on Cragwitch, who explains that in his youth, he and the other men discovered in Egypt an underground Rame Tep pyramid and the ancient tombs of five Egyptian princesses. Their find led to an angry uprising by the people of a nearby village. The protest was violently put down by the British Army, and a local boy of Anglo-Egyptian descent named Eh-Tar and his sister, orphaned by the attack, vowed to seek revenge and to replace the bodies of the five Egyptian princesses. The men returned safely to England, and Eh-Tar rebuilt the cult. While he is speaking, Cragwitch is shot through the window by a poisoned thorn. He tries to kill Holmes, but is knocked unconscious by Lestrade, who has reconsidered Holmes' advice after experiencing the hallucinations himself. As they return to the school, a chance remark by Watson causes Holmes to realize that Eh-Tar is none other than Professor Rathe.

Rathe and Mrs. Dribb, his sister, have abducted Elizabeth, planning to use her as the final sacrifice. Using Waxflatter's flying machine, Holmes and Watson reach the warehouse just in time to stop the sacrifice of Elizabeth. They accidentally burn down the temple, killing several cult members; Mrs. Dribb is shot through her own blowpipe and bursts into flames when her robes catch fire. Eh-Tar/Rathe escapes with Elizabeth and confronts Holmes on the frozen River Thames. When he tries to shoot Holmes, Elizabeth shields Holmes with her body. They duel, and Eh-Tar falls through the ice into the river, apparently to his death. A grief-stricken Holmes, weeping for the second and last time, cradles the dying Elizabeth, promising they will be reunited in a better world. She says "I’ll be waiting, and you'll be late as always."

Holmes transfers to another school, and Watson gives him a pipe as a Christmas/farewell present, completing the classic Sherlock Holmes costume. As narrator, Watson observes that he knew he would have more adventures at his friend’s side.

The credits roll over footage of a sleigh moving through an Alpine landscape. It eventually stops at an inn, where the passenger signs the register "Moriarty". He is none other than Professor Rathe/Eh-Tar, who has survived falling into the Thames, foreshadowing his role as Holmes' nemesis.

Cast[]

- Nicholas Rowe as Sherlock Holmes, the protagonist

- Alan Cox as John Watson

- Sophie Ward as Elizabeth Hardy, Holmes' love interest

- Anthony Higgins as Professor Rathe/Eh-Tar/Professor James Moriarty, ostensibly a teacher at Brompton School. He is in fact an Egyptian survivor of a massacre, seeking revenge against those who destroyed his home, killed his parents and disturbed five mummified Egyptian princesses, whose bodies he is replacing by kidnapping and killing girls. At the end of the movie, he assumes the name of Moriarty.

- Susan Fleetwood as Mrs Dribb, ostensibly the school nurse. She is Rathe/Eh-Tar's younger sister, his cult's second-in-command and chief assassin.

- Freddie Jones as Chester Cragwitch

- Nigel Stock as Rupert Waxflatter. Stock had previously played Watson in the 1965 television series of Sherlock Holmes.

- Roger Ashton-Griffiths as Inspector Lestrade

- Earl Rhodes as Dudley, Holmes' school rival

- Brian Oulton as Master Snelgrove, the boring chemistry teacher.

- Patrick Newell as Bentley Bobster

- Donald Eccles as Reverend Duncan Nesbitt

- Walter Sparrow as Ethan Engel

- Nadim Sawalha as Egyptian Tavern Owner

- Roger Brierley as Mr Holmes, Sherlock's father

- Vivienne Chandler as Mrs Holmes, Sherlock's mother

- Lockwood West as Curiosity Shop Owner

- John Scott Martin as Cemetery Caretaker

- Willoughby Goddard as School Reverend

- Michael Cule as Policeman With Lestrade

- Ralph Tabakin as Policeman in Shop Window, a policeman who observes Holmes and Watson using Professor Waxflatter's flying machine

- Nancy Nevinson as Hotel Receptionist, a woman who meets Rathe/Eh-Tar/Moriarty at the end of the film.

- Michael Hordern as Older John Watson (voice), the narrator of the story.

Production[]

While the film is based on characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the story is an original one penned by Chris Columbus. Though he admitted that he was "very worried about offending some of the Holmes purists",[2] Columbus used the original Doyle stories as his guide.[2] Of the creation of the film, Columbus stated:

"The thing that was most important to me was why Holmes became so cold and calculating, and why he was alone for the rest of his life," Mr. Columbus explains. "That's why he is so emotional in the film; as a youngster, he was ruled by emotion, he fell in love with the love of his life, and as a result of what happens in this film, he becomes the person he was later."[2]

When Steven Spielberg came aboard the project he wanted to make certain the script had the proper tone and captured the Victorian era.[3] He first had noted Sherlockian John Bennett Shaw read the screenplay and provide notes.[3] He then had English novelist Jeffrey Archer act as script doctor to anglicize the script and ensure authenticity.[3]

The cast includes actors with previous associations to Sherlock Holmes. Nigel Stock, who played Professor Waxflatter, portrayed Dr. Watson alongside both Douglas Wilmer and Peter Cushing in the BBC series of the 1960s.[4] Patrick Newell, who played Bentley Bobster, played both PC Benson in 1965's A Study in Terror[5] as well as Inspector Lestrade in 1979's Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson.[6] Cast member Alan Cox's father, actor Brian Cox, would later have a connection as well: he would play Dr. Joseph Bell, the inspiration for Holmes, in the television film The Strange Case of Sherlock Holmes & Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The movie explains where Holmes gains the attire popularly associated with him. His pipe is shown as being a Christmas present from Watson, the deerstalker hat originally belonged to Professor Waxflatter and is given to him by Elizabeth after the professor dies, and the cloak is taken from Rathe ("Call it a trophy; the skin of a leopard") after Holmes defeats him.

The film is notable for including the first fully computer-generated photorealistic animated character, a knight composed of elements from a stained glass window.[7] This effect was the first CG character to be scanned and painted directly onto film using a laser.[7] The effect was created by Lucasfilm's Industrial Light & Magic and John Lasseter[8]

In the United Kingdom and Australia, the film was titled Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear;[9] in Italy only "Pyramid of fear" (Piramide di paura).

The fencing scenes were shot at Penshurst Place in Kent.[10]

Music[]

The film music was composed and conducted by Bruce Broughton, who has a long-standing history of scoring orchestral film soundtracks. The music for the film was nominated for Grammy and also received a Saturn Award. The film soundtrack, released by MCA, was released on audio cassette and vinyl but not compact disc. A limited edition of the entire score was released as a promo CD in 2003; Intrada issued the entire score commercially in 2014.

MCA track listing:

- Main Title (1:58)

- Solving the Crime (4:53)

- Library Love/Waxflatter's First Flight (2:23)

- Pastries & Crypts (5:44)

- Waxing Elizabeth (3:35)

- Holmes and Elizabeth – Love Theme (1:54)

- Ehtar's Escape (4:02)

- The Final Duel (3:51)

- Final Farewell (1:53)

- The Riddle Solved/End Credits (6:25)

Intrada track listing, with tracks on the original release in bold:

Disc 1

- The First Victim (2:57)

- The Old Hat Trick (1:45)

- Main Title (2:01)

- Watson's Arrival (1:03)

- The Bear Riddle (:46)

- Library Love/Waxflatter's First Flight (2:54)

- Fencing With Rathe (1:07)

- The Glass Soldier (3:22)

- Solving The Crime (4:54)

- Second Attempt (1:11)

- Cold Revenge (4:08)

- Waxflatter's Death (3:38)

- The Hat (1:21)

- Holmes And Elizabeth – Love Theme (1:58)

Disc 2

- Getting The Point (6:25)

- Rame Tep (3:06)

- Pastries And Crypts (6:44)

- Discovered By Rathe (5:05)

- To Cragwitch's (1:32)

- The Explanation (1:48)

- Cragwitch Goes Again (1:23)

- It's You! (6:17)

- Waxing Elizabeth (3:37)

- Temple Fire (3:24)

- Ehtar's Escape (Revised Version) (4:04)

- Duel And Final Farewell (5:41)

- The Riddles Solved And End Credits (6:27)

- Ytrairom Spelled Backwards (:48)

- Main Title (Film Version) (1:42)

- Belly Dancer (1:02)

- Waxing Elizabeth (Chorus) (3:01)

- Waxing Elizabeth (Orchestra) (3:37)

- Ehtar's Escape (Original Version) (4:03)

- God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen (arr. Bruce Broughton) (01:06)

Illusionist David Copperfield used the music from the soundtrack for several segments of his The Magic of David Copperfield XIII: Mystery on the Orient Express television special, in which he levitated an entire train car from the famed Orient Express.[citation needed]

This is also one of only three Amblin Entertainment productions on which the logo is accompanied by the music composed for it by John Williams; the others are The Color Purple and The Money Pit.[citation needed]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The film was a box-office disappointment,[11] grossing around $19.7 million against an $18 million budget[12] and ranking 46th for the year at the North American box office.[13]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 64% based on reviews from 22 critics. The site's consensus states: "Young Sherlock Holmes is a charming, if unnecessarily flashy, take on the master sleuth."[14] On Metacritic the film has a score of 65% based on reviews from 15 critics.[15]

Roger Ebert gave the film 3 out of 4 stars, and wrote: "The elaborate special effects also seem a little out of place in a Sherlock Holmes movie, although I'm willing to forgive them because they were fun."[16] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune wrote: "The production is first-rate in all technical ways imaginable, but the villain that Holmes and Watson chase is not worth their intellect or time or ours."[17] Christopher Null of Filmcritic.com called the film "great fun".[18] Reviewing the film for The New York Times, Leslie Bennetts called it "a lighthearted murder mystery that weds Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to the kind of rollicking action-adventure that has made Steven Spielberg the most successful movie maker in the world".[2]

Colin Greenland reviewed Young Sherlock Holmes for White Dwarf #77, and stated that "Conan Doyle's creation is reduced to an irritating sequence of in-jokes about deerstalkers, violins and pipes. Instead of sleuthing we get swashbuckling in the blazing temple and swordplay on the frozen Thames; creditable acting, but a crass production from start to finish."[19]

Pauline Kael wrote, "This sounds like a funnier, zestier picture than it turns out to be. ... As long as the movie stays within the conceits of the Holmesian legends, it's mildly, blandly amusing. But when one of the imperilled old men gives an elaborate account of the background of the villainy ... your mind drifts and you lose the plot threads. And when the picture forsakes fog and coziness and the keenness of Holmes' intellect – when it starts turning him into a dashing action-adventure hero – the jig is up. ... the movie lets you down with a thump when Holmes and his companions enter a wooden pyramid-temple hidden under the London streets. ... There's a resounding hollowness at the center of this picture – Levinson's temple of doom".[20]

R.L. Shaffer writing for IGN in 2010, felt the film "doesn't hold up all that well" and that ultimately "the film shall remain a cult classic – loved by some, but forgotten by most."[21] DVD Verdict stated that the film was both "a reimagining of the detective's origin story, but it is also respectful of Arthur Conan Doyle's work" and "a joy from beginning to end."[22]

Awards[]

1985 – Academy Award For Visual Effects (nominated)[23][24][25]

1985 – Saturn Award for Best Music - Bruce Broughton (won)[26]

Video game[]

A video game based on the movie was released in 1987 for the MSX called Young Sherlock: The Legacy of Doyle released exclusively in Japan by Pack-In-Video. Although the game is based on the film, the plot of the game had little to do with the film's story.[27]

References[]

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1985-12-04). "Young Sherlock Holmes Movie Review (1985) | Roger Ebert". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Leslie Bennetts (December 1, 1985). "Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) IMAGINE SHERLOCK AS A BOY..." New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. pp. 406–407. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 308. ISBN 9780857687760.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 280. ISBN 9780857687760.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. pp. 198–199. ISBN 9780857687760.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Visual and Special Effects Film Milestones". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ "The history of CGI list". Listal.com. 2010-12-22. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 305. ISBN 9780857687760.

- ^ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Young Sherlock Holmes Film Focus".

- ^ Friendly, David T. (2000-07-05). "'Purple,' 'africa' Pace Box Office - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Domestic Box Office For 1985". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes". Metacritic. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ Roger Ebert (December 4, 1985). "Young Sherlock Holmes". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Gene Siskel (1985). "2 CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF A GOOD MYSTERY LOST IN 'YOUNG SHERLOCK'". ChicagoTribune.com.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes". Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Greenland, Colin (May 1986). "2020 Vision". White Dwarf. Games Workshop (77): 11.

- ^ Kael, Pauline. Hooked. New York: Dutton, 100-02.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes". IGN. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ "Young Sherlock Holmes". DVD Verdict. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ "Section 14: CGI in the movies". Design.osu.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-01-26. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ 1986|Oscars.org

- ^ Cocoon Wins Visual Effects: 1986 Oscars

- ^ Filmography|Bruce Broughton

- ^ Young Sherlock: The Legacy of Doyle for MSX (1987) - MobyGames

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Young Sherlock Holmes |

- Official website

- Young Sherlock Holmes at IMDb

- Young Sherlock Holmes at AllMovie

- Young Sherlock Holmes at Box Office Mojo

- Young Sherlock Holmes at the TCM Movie Database

- 1985 films

- English-language films

- 1980s adventure films

- 1980s mystery films

- 1980s stop-motion animated films

- 1980s teen films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American adventure films

- American films

- American mystery films

- American teen films

- Boarding school films

- Egyptian-language films

- Films directed by Barry Levinson

- Films scored by Bruce Broughton

- Films set in London

- Films set in Oxford

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- Films shot in Kent

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Films with screenplays by Chris Columbus

- Paramount Pictures films

- Sherlock Holmes films

- Sherlock Holmes pastiches

- Teen adventure films

- Teen mystery films