Qubes OS

| |

Qubes OS 4.0.3 running its default desktop environment, Xfce | |

| Developer | Invisible Things Lab |

|---|---|

| OS family | Linux (Unix-like) |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source (GPLv2), double license[1] |

| Initial release | September 3, 2012[2] |

| Latest release | 4.0.4[3] / March 4, 2021 |

| Latest preview | 4.1-rc3[4] / December 21, 2021 |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Update method | Yum (PackageKit) |

| Package manager | RPM Package Manager |

| Platforms | x86-64 |

| Kernel type | Microkernel (Xen Hypervisor running minimal Linux-based OSes and others) |

| Userland | Fedora, Debian, Whonix, Microsoft Windows |

| Default user interface | Xfce |

| License | Free software licenses (mainly GPL v2[5]) |

| Official website | qubes-os |

Qubes OS is a security-focused desktop operating system that aims to provide security through isolation.[6] Virtualization is performed by Xen, and user environments can be based on Fedora, Debian, Whonix, and Microsoft Windows, among other operating systems.[7][8]

Systems like Qubes are referred to in academia as Converged Multi-Level Secure (MLS) Systems.[9] Other proposals of similar systems have surfaced[10][11] and SecureView[12] is a commercial competitor, however Qubes OS is the only system of the kind actively being developed under a FOSS license.

Security goals[]

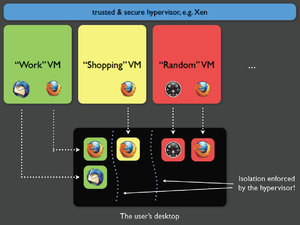

Qubes implements a Security by Isolation approach.[13] The assumption is that there can be no perfect, bug-free desktop environment: such an environment counts millions of lines of code and billions of software/hardware interactions. One critical bug in any of these interactions may be enough for malicious software to take control over a machine.[14][15]

To secure a desktop a Qubes user takes care to isolate various environments, so that if one of the components gets compromised, the malicious software would get access to only the data inside that environment.[16]

In Qubes, the isolation is provided in two dimensions: hardware controllers can be isolated into functional domains (e.g. network domains, USB controller domains), whereas the user's digital life is decided in domains with different levels of trust. For instance: work domain (most trusted), shopping domain, random domain (less trusted).[17] Each of those domains is run in a separate virtual machine.

Qubes virtual machines, by default, have passwordless root access (e.g. passwordless sudo).[18] UEFI Secure Boot is not supported out of the box, but this is not considered a major security issue.[19] Qubes is not a multiuser system.[20]

Installation and requirements[]

Qubes was not intended to be run as part of a multi-boot system because if an attacker were to take control of one of the other operating systems then they'd likely be able to compromise Qubes (e.g. before Qubes boots).[21] However, it is still possible to use Qubes as part of a multi-boot system and even to use grub2 as the boot loader/boot manager.[21] A standard Qubes installation takes all space on the storage medium (e.g. hard drive, USB flash drive) to which it is installed (not just all available free space) and it uses LUKS/dm-crypt full disk encryption.[19] It is possible (although not trivial) to customize much of the Qubes OS installation but for security reasons, this is discouraged for users that are not intimately familiar with Qubes. Qubes 4.x needs at least 32 GiB of disk space and 4 GB of RAM.[22] However, in practice it typically needs upwards of 6-8 GB of RAM since although it is possible to run it with only 4 GB of RAM, users will likely be limited to running no more than about three Qubes at a time.[19]

Since 2013, Qubes has not had support for 32-bit x86 architectures and now requires a 64-bit processor.[19] Qubes uses Intel VT-d/AMD's AMD-Vi, which is only available on 64-bit architectures, to isolate devices and drivers. The 64-bit architecture also provides a little more protection against some classes of attacks.[19] Since Qubes 4.x, Qubes requires either an Intel processor with support for VT-x with EPT and Intel VT-d virtualization technology or an AMD processor with support for AMD-V with RVI (SLAT) and AMD-Vi (aka AMD IOMMU) virtualization technology.[19] Qubes targets the desktop market. This market is dominated by laptops running Intel processors and chipsets and consequently, Qubes developers focus on Intel's VT-x/VT-d technologies.[23] This is not a major issue for AMD processors since AMD IOMMU is functionally identical to Intel's VT-d.[23]

User experience[]

The users interact with Qubes OS very much the same way they would interact with a regular desktop operating system. But there are some key differences:

- Each security domain (qube) is identified by a different colored window border

- Opening an application for the first time in that session for a particular security domain will take around 30s (depending on hardware)

- Copying files[24] and clipboard[25] is a little different since domains don't share clipboard or filesystem

- The user can create and manage security compartments

System architecture overview[]

Xen hypervisor and administrative domain (Dom0)[]

The hypervisor provides isolation between different virtual machines. The administrative domain, also referred to as Dom0 (a term inherited from Xen), has direct access to all the hardware by default. Dom0 hosts the GUI domain and controls the graphics device, as well as input devices, such as the keyboard and mouse. The GUI domain runs the X server, which displays the user desktop, and the window manager, which allows the user to start and stop the applications and manipulate their windows.

Integration of the different virtual machines is provided by the Application Viewer, which provides an illusion for the user that applications execute natively on the desktop, while in fact they are hosted (and isolated) in different virtual machines. Qubes integrates all these virtual machines onto one common desktop environment.

Because Dom0 is security-sensitive, it is isolated from the network. It tends to have as little interface and communication with other domains as possible in order to minimize the possibility of an attack originating from an infected virtual machine.[26][27]

The Dom0 domain manages the virtual disks of the other VMs, which are actually stored as files on the dom0 filesystem(s). Disk space is saved by virtue of various virtual machines (VM) sharing the same root file system in a read-only mode. Separate disk storage is only used for userʼs directory and per-VM settings. This allows software installation and updates to be centralized. It is also possible to install software only on a specific VM, by installing it as the non-root user, or by installing it in the non-standard, Qubes-specific /rw hierarchy.

Network domain[]

The network mechanism is the most exposed to security attacks. To circumvent this it is isolated in a separate, unprivileged virtual machine, called the Network Domain.

An additional firewall virtual machine is used to house the Linux-kernel-based firewall, so that even if the network domain is compromised due to a device driver bug, the firewall is still isolated and protected (as it is running in a separate Linux kernel in a separate VM).[28]

Application Virtual Machines (AppVM)[]

AppVMs are the virtual machines used for hosting user applications, such as a web browser, an e-mail client or a text editor. For security purposes, these applications can be grouped in different domains, such as "personal", "work", "shopping", "bank", etc. The security domains are implemented as separate, Virtual Machines (VMs), thus being isolated from each other as if they were executing on different machines.

Some documents or applications can be run in disposable VMs through an action available in the file manager. The mechanism follows the idea of sandboxes: after viewing the document or application, then the whole Disposable VM will be destroyed.[29]

Each security domain is labelled by a color, and each window is marked by the color of the domain it belongs to. So it is always clearly visible to which domain a given window belongs.

Reception[]

Security and privacy experts such as Edward Snowden, Daniel J. Bernstein, and Christopher Soghoian have publicly praised the project.[30]

Jesse Smith wrote review of Qubes OS 3.1 for DistroWatch Weekly:[31]

I had a revelation though on the second day of my trial when I realized I had been using Qubes incorrectly. I had been treating Qubes as a security enhanced Linux distribution, as though it were a regular desktop operating system with some added security. This quickly frustrated me as it was difficult to share files between domains, take screen shots or even access the Internet from programs I had opened in Domain Zero. My experience was greatly improved when I started thinking of Qubes as being multiple, separate computers which all just happened to share a display screen. Once I began to look at each domain as its own island, cut off from all the others, Qubes made a lot more sense. Qubes brings domains together on one desktop in much the same way virtualization lets us run multiple operating systems on the same server.

Kyle Rankin from Linux Journal reviewed Qubes OS in 2016:[32]

I'm sure you already can see a number of areas where Qubes provides greater security than you would find in a regular Linux desktop.

In 2014, Qubes was selected as a finalist of Access Innovation Prize 2014 for Endpoint Security, run by the international human rights organization Access Now.[33]

See also[]

- Whonix

- Tails (operating system)

References[]

- ^ "Qubes OS License".

- ^ "Introducing Qubes 1.0!". September 3, 2012.

- ^ "Qubes OS 4.0.4 has been released!". March 4, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Qubes OS 4.1-rc3 has been released!". December 21, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "License Qubes OS". www.qubes-os.org.

- ^ "Qubes OS bakes in virty system-level security". The Register. September 5, 2012.

- ^ "Qubes OS Templates".

- ^ "Installing and using Windows-based AppVMs".

- ^ Issa, Abdullah; Murray, Toby; Ernst, Gidon (December 4, 2018). "In search of perfect users: towards understanding the usability of converged multi-level secure user interfaces". Proceedings of the 30th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction. OzCHI '18: 30th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference. Melbourne Australia: ACM. p. 572576. doi:10.1145/3292147.3292231. ISBN 978-1-4503-6188-0. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Beaumont, Mark; McCarthy, Jim; Murray, Toby (December 5, 2016). "The cross domain desktop compositor: using hardware-based video compositing for a multi-level secure user interface". Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference on Computer Security Applications. ACSAC '16: 2016 Annual Computer Security Applications Conference. Los Angeles California USA: ACM. p. 533545. doi:10.1145/2991079.2991087. ISBN 978-1-4503-4771-6. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Atanas Filyanov; Nas, Aysegül; Volkamer, Melanie. "On the Usability of Secure GUIs": 11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "SecureView". AIS Home Assured Information Security. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ "The three approaches to computer security". Joanna Rutkowska. September 2, 2008.

- ^ "Qubes OS: An Operating System Designed For Security". Tom's hardware. August 30, 2011.

- ^ "A digital fortress?". The Economist. March 28, 2014.

- ^ "How Splitting a Computer Into Multiple Realities Can Protect You From Hackers". Wired. November 20, 2014.

- ^ "Partitioning my digital life into security domains". Joanna Rutkowska. March 13, 2011.

- ^ Passwordless Root Access in VMs

- ^ a b c d e f Qubes faq

- ^ Rutkowska, Joanna (May 3, 2010). "Google Groups - Qubes as a multi-user system". Google Groups.

- ^ a b Multibooting Qubes

- ^ Qubes system requirements

- ^ a b Why Intel VT-d ?

- ^ "Copying Files between qubes". Qubes OS. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Copy and Paste". Qubes OS. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "(Un)Trusting your GUI Subsystem". Joanna Rutkowska. September 9, 2010.

- ^ "The Linux Security Circus: On GUI isolation". Joanna Rutkowska. April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Playing with Qubes Networking for Fun and Profit". Joanna Rutkowska. September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Qubes To Implement Disposable Virtual Machines". OSnews. June 3, 2010.

- ^ "Endpoint Security Prize Finalists Announced!".

- ^ DistroWatch Weekly, Issue 656, 11 April 2016

- ^ Secure Desktops with Qubes: Introduction | Linux Journal

- ^ "Endpoint Security Prize Finalists Announced!". Michael Carbone. February 13, 2014.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qubes OS. |

- Operating system security

- RPM-based Linux distributions

- X86-64 Linux distributions

- 2012 software

- Linux distributions