Radio Ga Ga

| "Radio Ga Ga" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

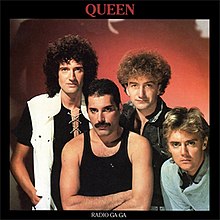

UK single picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by Queen | ||||

| from the album The Works | ||||

| A-side | "Radio Ga Ga" (Extended Version) (12" single only)[1] | |||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released | 16 January 1984[2] | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | Roger Taylor | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Queen singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Radio Ga Ga" on YouTube | ||||

"Radio Ga Ga" is a 1984 song performed and recorded by the British rock band Queen, written by their drummer Roger Taylor. It was released as a single with "I Go Crazy" by Brian May as the B-side. It was included on the album The Works and is also featured on the band's compilation albums Greatest Hits II and Classic Queen.[5]

The single was a worldwide success for the band, reaching number one in 19 countries, number two on the UK Singles Chart and the Australian Kent Music Report and number 16 on the US Billboard Hot 100.[6][7] The band performed the song at every concert from 1984 to their last concert with lead singer Freddie Mercury in 1986, including their performance at Live Aid in 1985.[8][9][10][11]

The music video for the song uses footage from the 1927 silent science fiction film Metropolis. It received heavy rotation on music channels and was nominated for an MTV Video Music Award in 1984.[12]

Meaning[]

"Radio Ga Ga" was released in 1984. It was a commentary on television overtaking radio's popularity and how one would listen to radio in the past for a favourite comedy, drama, or science fiction programme. It also addressed the advent of the music video and MTV, which was then competing with radio as an important medium for promoting records. At the 1984 MTV Video Music Awards the video for "Radio Ga Ga" would receive a Best Art Direction nomination.[13] Roger Taylor was quoted:

That's part of what the song's about, really. The fact that they [music videos] seem to be taking over almost from the aural side, the visual side seems to be almost more important.[14]

The song makes reference to two important radio events of the 20th century; Orson Welles' 1938 broadcast of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds in the lyric "through wars of worlds/invaded by Mars", and Winston Churchill's 18 June 1940 "This was their finest hour" speech from the House of Commons, in the lyric "You've yet to have your finest hour".[15]

Recording[]

The inspiration for this song came when Roger Taylor heard his son utter the words "radio ca-ca" while listening to a bad song on the radio while they were in Los Angeles.[16] After hearing the phrase, Taylor began writing the song when he locked himself in a room with a Roland Jupiter-8 and a drum machine (Linn LM-1). He thought it would fit his solo album, but when the band heard it, John Deacon wrote a bassline and Freddie Mercury reconstructed the track, thinking it could be a big hit. Taylor then took a skiing holiday and let Mercury polish the lyrics, harmony, and arrangements of the song. Recording sessions began at Record Plant Studios in Los Angeles in August 1983 – the band's only time recording in North America.[17] It included Canadian session keyboardist Fred Mandel. Mandel programmed the Jupiter's arpeggiated synth-bass parts. The recording features prominent use of the Roland VP330+ vocoder. The bassline was produced by a Roland Jupiter-8, using the built-in arpeggiator.[18]

Track listings[]

7" single[1]

- A-side. "Radio Ga Ga" (Album Version)

- B-side. "I Go Crazy" (Single Version)

12" single[1]

- A-side. "Radio Ga Ga" (Extended Version)

- B1. "Radio Ga Ga" (Instrumental Version)

- B2. "I Go Crazy" (Single Version)

Music video[]

David Mallet's music video for the song features scenes from Fritz Lang's 1927 German expressionist science fiction film Metropolis and was filmed at Carlton TV Studios and Shepperton Studios, London, between 23/24 November 1983 and January 1984.[19] It leads to a 1984 re-release of the film with a rock soundtrack[20] Mercury's solo song "Love Kills" was used in Giorgio Moroder's restored version of the film and in exchange Queen were granted the rights to use footage from it in their "Radio Ga Ga" video. However, Queen had to buy performance rights to the film from the communist East German government, which was the copyright holder at the time.[21] At the end of the music video, the words "Thanks To Metropolis" appear. The video also features footage from earlier Queen promo videos.[19]

Live versions[]

Queen finished their sets before the encores on The Works Tour with "Radio Ga Ga" and Mercury would normally sing "you had your time" in a lower octave and modify the deliveries of "you had the power, you've yet to have your finest hour" while Roger Taylor sang the pre-chorus in the high octave. Live versions from the 1984/85 tour were recorded and filmed for the concert films Queen Rock in Rio 1985 and Final Live in Japan 1985.[22] As heard on bootleg recordings, Deacon can be heard providing backing vocals to the song; it is one of the very few occasions he sang in concert.

"I remember thinking 'oh great, they've picked it up' and then I thought 'this is not a Queen audience'. This is a general audience who've bought tickets before they even knew we were on the bill. And they all did it. How did they know? Nobody told them to do it."

—Brian May on the audience participation in clapping to "Radio Ga Ga" at Live Aid.[23]

Queen played a shorter, up-tempo version of "Radio Ga Ga" during the Live Aid concert on 13 July 1985 at Wembley Stadium, where Queen's "show-stealing performance" had 72,000 people clapping in unison.[8][24] It was the second song the band performed at Live Aid after opening with "Bohemian Rhapsody".[9][25] "Radio Ga Ga" became a live favourite thanks largely to the audience participation potential of the clapping sequence prompted by the rhythm of the chorus (copied from the video). Mercury sang all high notes in this version. The song was played for the Magic Tour a year later, including twice more at Wembley Stadium; it was recorded for the live album Live at Wembley '86, VHS Video and DVD on 12 July 1986, the second night in the venue.[11]

Paul Young performed the song with Queen at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert again at Wembley Stadium on 20 April 1992.[26] At the "Party at the Palace" concert, celebrating Queen Elizabeth II's Golden Jubilee in 2002, "Radio Ga Ga" opened up Queen's set with Roger Taylor on vocals and Phil Collins on the drums.[27]

This song was played on the Queen + Paul Rodgers Tour in 2005–2006 and sung by Roger Taylor and Paul Rodgers. It was recorded officially at the Hallam FM Arena in Sheffield on 5 May 2005. The result, Return of the Champions, was released on CD and DVD on 19 September 2005 and 17 October 2005. It was also played on the Rock the Cosmos Tour during late 2008, this time with only Rodgers on lead vocals. The concert album Live in Ukraine came as a result of this tour, yet the song is not available on the CD or DVD versions released 15 June 2009. This performance of "Radio Ga Ga" is only available as a digital download from iTunes. It was again played on the Queen + Adam Lambert Tour with Lambert on lead vocals.[28][29]

Charts[]

Weekly charts[]

Live Aid version[]

|

Year-end charts[]

Live Aid version[]

Queen + Paul Rodgers version[]

|

Certifications[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[67] | Gold | 45,000 |

| Italy (FIMI)[68] | Platinum | 50,000 |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[69] | Platinum | 600,000 |

| United States (RIAA)[70] | Platinum | 1,000,000 |

|

| ||

Influences[]

American pop singer Lady Gaga credits her stage name to this song.[71][72] She stated that she "adored" Queen, and that they had a hit called 'Radio Ga Ga'. "That's why I love the name".[73]

See also[]

- List of Dutch Top 40 number-one singles of 1984

- List of European number-one hits of 1984

- List of number-one singles of 1984 (Ireland)

- List of number-one singles and albums in Sweden

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Queen UK Singles Discography (1984–1991)". Ultimate Queen. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "News: Predictions 1984". Record Mirror. 31 December 1983. p. 4. Retrieved 16 December 2020 – via Flickr.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Furniss, Matters (2012). Queen – Uncensored On the Record. Coda Books Ltd. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-9085-3884-0.

- ^ Stereo Review. 49. CBS Publications. 1984. p. 76.

Radio Gaga (the single), a skillful merger of contemporary synth-pop and old-time Brill Building panache

- ^ "Classic Queen by Queen". MTV. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Lazell, Barry (1989). Rock movers & shakers. Billboard Publications, Inc. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-8230-7608-6.

- ^ "Queen Biography for 1984". QueenZone.com. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Queen win greatest live gig poll". BBC News. 9 November 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stanford, Peter (24 September 2011). "Queen: their finest moment at Live Aid". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Queen live on tour: The Works 1985". Queen Concerts. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Queen live on tour: Magic tour". Queen Concerts. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Giles, Jeff. "That Time Classic Rock Cleaned Up at the First-Ever MTV Video Music Awards". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "1984 MTV Video Music Awards". Rock on the Net. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Roger Taylor & John Deacon – 1984 Breakfast Time Interview". YouTube. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Avery, Todd (2006). Radio Modernism: Literature, Ethics, and the BBC 1922-1938. Ashgate Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7546-5517-6.

- ^ Roger Taylor speaking in the documentary Queen – Days of Our Lives

- ^ Purvis, Georg (2007). Queen: Complete Works. Reynolds & Hearn. p. 236.

- ^ "Instruments on Queen and solo tours". Queen Concerts. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Queen Promo Videos". Ultimate Queen. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Brode, Douglas (2015). Fantastic Planets, Forbidden Zones, and Lost Continents: The 100 Greatest Science-Fiction Films. University of Texas Press. p. 6.

- ^ Brooks, Greg; Taylor, Gary. "The Works – Album Details". Queenonline.com. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Purvis, Georg (2007). Queen: Complete Works. Reynolds & Hearn. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-90528-733-8.

- ^ Thomas, David (August 1999). "Their Britannic Majesties Request". Mojo Magazine. No. 69. p. 87. ISSN 1351-0193.

- ^ Ryan Minchin, dir. (2005). "Queen Voted Best Gig-Live Aid". YouTube. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Queen live on tour: Festivals, parties, TV". Queen Concerts. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert". Ultimate Queen. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Queen Miscellaneous Live Song Lyrics". Ultimate Queen. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (14 January 2015). "Queen and Adam Lambert review – an unlikely union, but it works". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Shafer, Ellise (21 July 2019). "Queen and Adam Lambert Play the Hits, Pay Tribute to Freddie Mercury at L.A. Concert". Billboard. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970-1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 243. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Queen – Radio Ga Ga" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Queen – Radio Ga Ga" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 6262." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Danske Hitlister". Danskehitlister.dk. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016.

- ^ "UK, Eurochart, Billboard & Cashbox No.1 Hits". MusicSeek.info. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006.

- ^ Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- ^ "Accès direct aux Artistes (Q)". InfoDisc (in French). Select "Queen" from the artist drop-down menu. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Radio Ga Ga". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 8, 1984" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40 Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Queen – Radio Ga Ga" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". VG-lista. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "South African Rock Lists Website SA Charts 1969 – 1989 Acts (Q)". Rock.co.za. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Queen Chart History (Dance Club Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Queen - Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "CASH BOX Top 100 Singles – Week ending APRIL 14, 1984". Cash Box. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Hot Canadian Digital Song Sales". Billboard. 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Queen – Radio Ga Ga" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". Top Digital Download. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Queen Chart History (Japan Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Queen Chart History (Hot Rock Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Forum - ARIA Charts: Special Occasion Charts – Top 100 End of Year AMR Charts – 1980s". Australian-charts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade 1984" (in German). Austrian-charts.com. Hung Medien. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 1984" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Top 100 Singles of 1984". RPM. Vol. 41 no. 17. Library and Archives Canada. 5 January 1985. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 1984" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Single 1984" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Hung Medien. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1984" (in German). Hitparade.ch. Hung Medien. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "The CASH BOX Year-End Charts: 1984". Cash Box. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Year-End Charts: Hot Rock Songs". Billboard. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Top 3000 Singles + EPs Digitais: Semanas 01 a 52 de 2019 de 28/12/2018 a 26/12/2019" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – Queen – Radio Ga Ga" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 18 November 2019. Select "2019" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "Radio Ga Ga" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Singoli" under "Sezione".

- ^ "British single certifications – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "American single certifications – Queen – Radio Ga Ga". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Martin, Gavin (8 January 2009). "Lady GaGa the new Princess of Pop". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Rose, Lisa (21 January 2010). "Lady Gaga's outrageous persona born in Parsippany, New Jersey". NJ.com. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Dingwall, John (27 November 2009). "The Fear Factor; Lady Gaga used tough times as inspiration for her new album". Daily Record. pp. 48–49. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

External links[]

- Official YouTube videos: original music video, Big Spender/ Radio Ga Ga (Live At Wembley), Queen + Paul Rodgers, at Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert

- Lyrics from Queen official site: lyrics from Live Magic version, lyrics from Live at Wembley '86 version.

- Radio Ga Ga performed by Prisoners in the Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitational Centre

- 1984 songs

- 1984 singles

- British pop rock songs

- British synth-pop songs

- Capitol Records singles

- Dutch Top 40 number-one singles

- EMI Records singles

- European Hot 100 Singles number-one singles

- Hollywood Records singles

- Irish Singles Chart number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Finland

- Number-one singles in Poland

- Number-one singles in Sweden

- Queen (band) songs

- Song recordings produced by Reinhold Mack

- Songs about radio

- Songs written by Roger Taylor (Queen drummer)

- Ultratop 50 Singles (Flanders) number-one singles

- Music videos directed by David Mallet (director)

- Works based on Metropolis (1927 film)