Roe v. Wade

| Roe v. Wade | |

|---|---|

Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Argued December 13, 1971 Reargued October 11, 1972 Decided January 22, 1973 | |

| Full case name | Jane Roe, et al. v. Henry Wade, District Attorney of Dallas County |

| Citations | 410 U.S. 113 (more) 93 S. Ct. 705; 35 L. Ed. 2d 147; 1973 U.S. LEXIS 159 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Reargument | Reargument |

| Decision | Opinion |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for plaintiffs, injunction denied, 314 F. Supp. 1217 (N.D. Tex. 1970); probable jurisdiction noted, 402 U.S. 941 (1971); set for reargument, 408 U.S. 919 (1972) |

| Subsequent | Rehearing denied, 410 U.S. 959 (1973) |

| Holding | |

| The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a fundamental "right to privacy" that protects a pregnant woman's liberty to choose whether or not to have an abortion. This right is not absolute, and must be balanced against the government's interests in protecting women's health and protecting prenatal life. Texas law making it a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion violated this right. | |

| Court membership | |

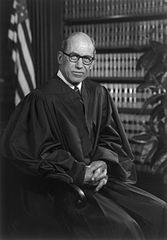

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell |

| Concurrence | Burger |

| Concurrence | Douglas |

| Concurrence | Stewart |

| Dissent | White, joined by Rehnquist |

| Dissent | Rehnquist |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Amend. XIV; Tex. Code Crim. Proc. arts. 1191–94, 1196 | |

Overruled by | |

| (partially) Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) | |

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973),[1] was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protects a pregnant woman's liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction. It struck down many U.S. federal and state abortion laws,[2][3] and prompted an ongoing national debate in the United States about whether and to what extent abortion should be legal, who should decide the legality of abortion, what methods the Supreme Court should use in constitutional adjudication, and what the role of religious and moral views in the political sphere should be. Roe v. Wade reshaped American politics, dividing much of the United States into abortion rights and anti-abortion movements, while activating grassroots movements on both sides.

The decision involved the case of Norma McCorvey—known in her lawsuit under the pseudonym "Jane Roe"—who in 1969 became pregnant with her third child. McCorvey wanted an abortion, but she lived in Texas, where abortion was illegal except when necessary to save the mother's life. She was referred to lawyers Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, who filed a lawsuit on her behalf in U.S. federal court against her local district attorney, Henry Wade, alleging that Texas's abortion laws were unconstitutional. A three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas heard the case and ruled in her favor. Texas then appealed this ruling directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In January 1973, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision ruling that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a "right to privacy" that protects a pregnant woman's right to choose whether or not to have an abortion. But it also ruled that this right is not absolute, and must be balanced against the government's interests in protecting women's health and protecting prenatal life.[4][5] The Court resolved this balancing test by tying state regulation of abortion to the three trimesters of pregnancy: during the first trimester, governments could not prohibit abortions at all; during the second trimester, governments could require reasonable health regulations; during the third trimester, abortions could be prohibited entirely so long as the laws contained exceptions for cases when they were necessary to save the life or health of the mother.[5] The Court classified the right to choose to have an abortion as "fundamental", which required courts to evaluate challenged abortion laws under the "strict scrutiny" standard, the highest level of judicial review in the United States.[6]

Roe was criticized by some in the legal community,[7] and some have called the decision a form of judicial activism.[8] In 1992, the Supreme Court revisited and modified its legal rulings in Roe in the case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey.[9] In Casey, the Court reaffirmed Roe's holding that a woman's right to choose to have an abortion is constitutionally protected, but abandoned Roe's trimester framework in favor of a standard based on fetal viability, and overruled Roe's requirement that government regulations on abortion be subjected to the strict scrutiny standard.[4][10]

Background

History of abortion laws in the United States

According to the Court, "the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage". Providing a historical analysis on abortion, Justice Harry Blackmun noted that abortion was "resorted to without scruple" in Greek and Roman times.[11] Blackmun also addressed the permissive and restrictive abortion attitudes and laws throughout history, noting the disagreements among leaders (of all different professions) in those eras and the formative laws and cases.[12] In the United States, in 1821, Connecticut passed the first state statute criminalizing abortion. Every state had abortion legislation by 1900.[13] In the United States, abortion was sometimes considered a common law crime,[14] though Justice Blackmun would conclude that the criminalization of abortion did not have "roots in the English common-law tradition".[15] Rather than arresting the women having the abortions, legal officials were more likely to interrogate these women to obtain evidence against the abortion provider in order to close down that provider's business.[16][17]

In 1971, Shirley Wheeler was charged with manslaughter after Florida hospital staff reported her illegal abortion to the police. She received a sentence of two years' probation and, under her probation, had to move back into her parents' house in North Carolina.[16] The Boston Women's Abortion Coalition held a rally for Wheeler in Boston to raise money and awareness of her charges as well as had staff members from the Women's National Abortion Action Coalition (WONAAC) speak at the rally.[18] Wheeler was possibly the first woman to be held criminally responsible for submitting to an abortion.[19] Her conviction was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court.[16]

With the passage of the California Therapeutic Abortion Act[20] in 1967, abortion became essentially legal on demand in that state. Pregnant women in other states could travel to California to obtain legal abortions—if they could afford to. A flight from Dallas to Los Angeles was nicknamed "the abortion special" because so many of its passengers were traveling for that reason. There were prepackaged trips known as the "non-family plan".[21]

History of the case

In June 1969, 21-year-old Norma McCorvey discovered she was pregnant with her third child. She returned to Dallas, where friends advised her to falsely claim that she had been raped, incorrectly believing that Texas law allowed abortion in cases of rape and incest when it actually allowed abortion only "for the purpose of saving the life of the mother". She attempted to obtain an illegal abortion, but found that the unauthorized facility had been closed down by the police. Eventually, she was referred to attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington.[22][23] McCorvey would end up giving birth before the case was decided, and the child was put up for adoption.[24]

In 1970, Coffee and Weddington filed suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas on behalf of McCorvey (under the alias Jane Roe). The defendant in the case was Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade, who represented the State of Texas. McCorvey was no longer claiming her pregnancy was a result of rape, and later acknowledged that she had lied about having been raped, in hope to circumvent a Texas law that banned abortions except when the woman's life is in danger.[25][26][27] "Rape" is not mentioned in the judicial opinions in the case.[28]

On June 17, 1970, a three-judge panel of the District Court, consisting of Northern District of Texas Judges Sarah T. Hughes, William McLaughlin Taylor Jr. and Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Irving Loeb Goldberg, unanimously[28] declared the Texas law unconstitutional, finding that it violated the right to privacy found in the Ninth Amendment. In addition, the court relied on Justice Arthur Goldberg's 1965 concurrence in Griswold v. Connecticut. The court, however, declined to grant an injunction against enforcement of the law.[29]

Issues before the Supreme Court

Oral arguments and initial discussions

Roe v. Wade reached the Supreme Court on appeal in 1970. The justices delayed taking action on Roe and a closely related case, Doe v. Bolton, until they had decided Younger v. Harris (because they felt the appeals raised difficult questions on judicial jurisdiction) and United States v. Vuitch (in which they considered the constitutionality of a District of Columbia statute that criminalized abortion except where the mother's life or health was endangered). In Vuitch, the Court narrowly upheld the statute, though in doing so, it treated abortion as a medical procedure and stated that physicians must be given room to determine what constitutes a danger to (physical or mental) health. The day after they announced their decision in Vuitch, they voted to hear both Roe and Doe.[30]

Arguments were scheduled by the full Court for December 13, 1971. Before the Court could hear the oral arguments, Justices Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II retired. Chief Justice Warren Burger asked Justice Potter Stewart and Justice Blackmun to determine whether Roe and Doe, among others, should be heard as scheduled. According to Blackmun, Stewart felt that the cases were a straightforward application of Younger v. Harris, and they recommended that the Court move forward as scheduled.[31]

In his opening argument in defense of the abortion restrictions, attorney Jay Floyd made what was later described as the "worst joke in legal history".[32] Appearing against two female lawyers, Floyd began, "Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court. It's an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word." His remark was met with cold silence; one observer thought that Chief Justice Burger "was going to come right off the bench at him. He glared him down."[33][34]

After a first round of arguments, all seven justices tentatively agreed that the Texas law should be struck down, but on varying grounds.[35] Burger assigned the role of writing the Court's opinion in Roe (as well as Doe) to Blackmun, who began drafting a preliminary opinion that emphasized what he saw as the Texas law's vagueness.[36] (At this point, Black and Harlan had been replaced by Justices William Rehnquist and Lewis F. Powell Jr., but they arrived too late to hear the first round of arguments.) But Blackmun felt that his opinion did not adequately reflect his liberal colleagues' views.[37] In May 1972, he proposed that the case be reargued. Justice William O. Douglas threatened to write a dissent from the reargument order (he and the other liberal justices were suspicious that Rehnquist and Powell would vote to uphold the statute), but was coaxed out of the action by his colleagues, and his dissent was merely mentioned in the reargument order without further statement or opinion.[38][39] The case was reargued on October 11, 1972. Weddington continued to represent Roe, and Texas Assistant Attorney General Robert C. Flowers replaced Jay Floyd for Texas.[40]

Drafting the opinion

Blackmun continued to work on his opinions in both cases over the summer recess, even though there was no guarantee that he would be assigned to write them again. Over the recess, he spent a week researching the history of abortion at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he had worked in the 1950s. After the Court heard the second round of arguments, Powell said he would agree with Blackmun's conclusion but pushed for Roe to be the lead of the two abortion cases being considered. Powell also suggested that the Court strike down the Texas law on privacy grounds. Justice Byron White was unwilling to sign on to Blackmun's opinion, and Rehnquist had already decided to dissent.[41]

Prior to the decision, the justices discussed the trimester framework at great length. Justice Powell had suggested that the point where the state could intervene be placed at viability, which Justice Thurgood Marshall supported as well.[42] In an internal memo to the other justices before the majority decision was published, Justice Blackmun wrote: "You will observe that I have concluded that the end of the first trimester is critical. This is arbitrary, but perhaps any other selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary."[43] Roe supporters are quick to point out, however, that the memo only reflects Blackmun's uncertainty about the timing of the trimester framework, not the framework or the holding itself.[44] Contrary to Blackmun, Justice Douglas preferred the first-trimester line.[45] Justice Stewart said the lines were "legislative" and wanted more flexibility and consideration paid to state legislatures, though he joined Blackmun's decision.[46] Justice William J. Brennan Jr. proposed abandoning frameworks based on the age of the fetus and instead allowing states to regulate the procedure based on its safety for the mother.[45]

Supreme Court decision

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision in favor of Norma McCorvey ("Jane Roe") that held that women in the United States have a fundamental right to choose whether or not to have abortions without excessive government restriction, and struck down Texas's abortion ban as unconstitutional. The decision was issued together with a companion case, Doe v. Bolton, that involved a similar challenge to Georgia's abortion laws.

Opinion of the Court

Seven justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by Justice Harry Blackmun. The opinion recited the facts of the case, then dealt with issues of procedure and justiciability before proceeding to the main constitutional issues of the case.

Standing

The Court's opinion first addressed the legal issues of standing and mootness. Under the traditional interpretation of these rules, Norma McCorvey's ("Jane Roe") appeal was moot because she had already given birth to her child and thus would not be affected by the ruling; she also lacked standing to assert the rights of other pregnant women.[47] As she did not present an "actual case or controversy" (a grievance and a demand for relief), any opinion issued by the Supreme Court would constitute an advisory opinion.[48]

The Court concluded that the case came within an established exception to the rule: one that allowed consideration of an issue that was "capable of repetition, yet evading review".[49] This phrase had been coined in 1911 by Justice Joseph McKenna in Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. ICC.[50] Blackmun's opinion quoted McKenna and noted that pregnancy would normally conclude more quickly than an appellate process: "If that termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation seldom will survive much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be effectively denied."[51]

Abortion and right to privacy

After dealing with standing, the Court then proceeded to the main issue of the case: the constitutionality of Texas's abortion law. The Court first surveyed abortion's legal status throughout the history of Roman law and the Anglo-American common law.[5] It also reviewed the developments of medical procedures and technology used in abortions, which had only become reliably safe in the early 20th century.[5]

After its historical survey, the Court introduced the concept of a constitutional "right to privacy" that was intimated in earlier cases involving parental control over childrearing—Meyer v. Nebraska and Pierce v. Society of Sisters—and reproductive autonomy with the use of contraception—Griswold v. Connecticut.[5] Then, "with virtually no further explanation of the privacy value",[6] the Court ruled that regardless of exactly which of its provisions were involved, the U.S. Constitution's guarantees of liberty covered a right to privacy that generally protected a pregnant woman's decision whether or not to abort a pregnancy.[5]

This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or ... in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 153.[52]

The Court reasoned that outlawing abortions would infringe a pregnant woman's right to privacy for several reasons: having unwanted children "may force upon the woman a distressful life and future"; it may bring imminent psychological harm; caring for the child may tax the mother's physical and mental health; and because there may be "distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child".[53]

But the Court rejected the notion that this right to privacy was absolute.[5] It held instead that the abortion right must be balanced against other government interests.[5] The Court found two government interests that were sufficiently "compelling" to permit states to impose some limitations on the right to choose to have an abortion: first, protecting the mother's health, and second, protecting the life of the fetus.[5]

A State may properly assert important interests in safeguarding health, maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life. At some point in pregnancy, these respective interests become sufficiently compelling to sustain regulation of the factors that govern the abortion decision. ... We, therefore, conclude that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 154.

The state of Texas had argued that total bans on abortion were justifiable because "life" begins at the moment of conception, and therefore its governmental interest in protecting prenatal life should apply to all pregnancies regardless of their stage.[6] But the Court found that there was no indication that the Constitution's uses of the word "person" were meant to include fetuses, and so it rejected Texas's argument that a fetus should be considered a "person" with a legal and constitutional right to life.[5] It noted that there was still great disagreement over when an unborn fetus becomes a living being.[54]

We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, in this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 159.[55]

The Court settled on the three trimesters of pregnancy as the framework to resolve the problem. During the first trimester, when it was believed that the procedure was safer than childbirth, the Court ruled that the government could place no restriction on a woman's ability to choose to abort a pregnancy other than minimal medical safeguards such as requiring a licensed physician to perform the procedure.[6] From the second trimester on, the Court ruled that evidence of increasing risks to the mother's health gave the state a compelling interest, and that it could enact medical regulations on the procedure so long as they were reasonable and "narrowly tailored" to protecting mothers' health.[6] The beginning of the third trimester was considered to be the point at which a fetus became viable under the medical technology available in the early 1970s, so the Court ruled that during the third trimester the state had a compelling interest in protecting prenatal life, and could legally prohibit all abortions except where necessary to protect the mother's life or health.[6]

The Court concluded that Texas's abortion statutes were unconstitutional, and struck them down:

A state criminal abortion statute of the current Texas type, that excepts from criminality only a life-saving procedure on behalf of the mother, without regard to pregnancy stage and without recognition of the other interests involved, is violative of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 164.

Concurrences

Several other justices filed concurring opinions in the case. Justice Potter Stewart wrote a concurring opinion in which he stated that even though the Constitution makes no mention of the right to choose to have an abortion without interference, he thought the Court's decision was a permissible interpretation of the doctrine of substantive due process, which says that the Due Process Clause's protection of liberty extends beyond simple procedures and protects certain fundamental rights.[56][6] Justice William O. Douglas wrote a concurring opinion in which he described how he believed that while the Court was correct to find that the right to choose to have an abortion was a fundamental right, it would be better to derive it from the Ninth Amendment—which states that the fact that a right is not specifically enumerated in the Constitution shall not be construed to mean that American people do not possess it—rather than through the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause.[56][6] Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote a concurrence in which he wrote that he thought it would be permissible to allow a state to require two physicians to certify an abortion before it could be performed.[56]

Dissents

Two justices dissented from the Court's decision, and their dissenting opinions touched on points that would lead to later criticism of the Roe decision.[6]

Justice Byron White's dissent was issued with Roe's companion case, Doe v. Bolton, and describes his belief that the Court had no basis for deciding between the competing values of pregnant women and unborn children. He believed that the legality of abortion should "be left with the people and the political processes the people have devised to govern their affairs".[57]

I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court's judgment. The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant women and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. The upshot is that the people and the legislatures of the 50 States are constitutionally disentitled to weigh the relative importance of the continued existence and development of the fetus, on the one hand, against a spectrum of possible impacts on the woman, on the other hand. As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.

— Doe, 410 U.S. at 221–22 (White, J., dissenting).

Justice William Rehnquist's dissent compared the majority's use of substantive due process to the Court's repudiated use of the doctrine in the 1905 case Lochner v. New York.[6] He elaborated on several of White's points, asserting that the Court's historical analysis was flawed:

To reach its result, the Court necessarily has had to find within the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment a right that was apparently completely unknown to the drafters of the Amendment. As early as 1821, the first state law dealing directly with abortion was enacted by the Connecticut Legislature. By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, there were at least 36 laws enacted by state or territorial legislatures limiting abortion. While many States have amended or updated their laws, 21 of the laws on the books in 1868 remain in effect today.

From this historical record, Rehnquist concluded, "There apparently was no question concerning the validity of this provision or of any of the other state statutes when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted." Therefore, in his view, "the drafters did not intend to have the Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the power to legislate with respect to this matter."[61]

Reception

Political

A statistical evaluation of the relationship of political affiliation to abortion rights and anti-abortion issues shows that public opinion is much more nuanced about when abortion is acceptable than is commonly assumed.[62] The most prominent organized groups that mobilized in response to Roe are the National Abortion Rights Action League and the National Right to Life Committee.

Support

Advocates of Roe describe it as vital to the preservation of women's rights, personal freedom, bodily integrity, and privacy. Advocates have also reasoned that access to safe abortion and reproductive freedom generally are fundamental rights. Some scholars (not including any member of the Supreme Court) have equated the denial of abortion rights to compulsory motherhood, and have argued that abortion bans, therefore, violate the Thirteenth Amendment:

When women are compelled to carry and bear children, they are subjected to 'involuntary servitude' in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. Even if the woman has stipulated to have consented to the risk of pregnancy, that does not permit the state to force her to remain pregnant.[63]

Supporters of Roe contend that the decision has a valid constitutional foundation in the Fourteenth Amendment, or that the fundamental right to abortion is found elsewhere in the Constitution but not in the articles referenced in the decision.[63][64]

Opposition

Every year, on the anniversary of the decision, opponents of abortion march up Constitution Avenue to the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., in the March for Life.[65] Around 250,000 people attended the march until 2010.[66][67] Estimates put the 2011 and 2012 attendances at 400,000 each,[68] and the 2013 March for Life drew an estimated 650,000 people.[69]

Opponents of Roe assert that the decision lacks a valid constitutional foundation.[70] Like the dissenters in Roe, they maintain that the Constitution is silent on the issue, and that proper solutions to the question would best be found via state legislatures and the legislative process, rather than through an all-encompassing ruling from the Supreme Court.[71]

A prominent argument against the Roe decision is that, in the absence of consensus about when meaningful life begins, it is best to avoid the risk of doing harm.[72]

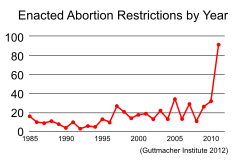

In response to Roe v. Wade, most states enacted or attempted to enact laws limiting or regulating abortion, such as laws requiring parental consent or parental notification for minors to obtain abortions; spousal mutual consent laws; spousal notification laws; laws requiring abortions to be performed in hospitals, not clinics; laws barring state funding for abortions; laws banning intact dilation and extraction, also known as partial-birth abortion; laws requiring waiting periods before abortions; and laws mandating that women read certain types of literature and watch a fetal ultrasound before undergoing an abortion.[73] In 1976, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, barring federal funding of abortions (except in cases of rape, incest, or a threat to the life of the mother) for poor women through the Medicaid program. The Supreme Court struck down some state restrictions in a long series of cases stretching from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s, but upheld restrictions on funding, including the Hyde Amendment, in the case of Harris v. McRae (1980).[74]

Some opponents of abortion maintain that personhood begins at fertilization or conception, and should therefore be protected by the Constitution;[64] the dissenting justices in Roe instead wrote that decisions about abortion "should be left with the people and to the political processes the people have devised to govern their affairs."[75]

In 1995, Norma L. McCorvey revealed that she had become anti-abortion, and from then until her death in 2017, she was a vocal opponent of abortion.[76] In a documentary filmed before her death in 2017 she restated her support for abortion, and said that she had been paid by anti-abortion groups, including Operation Rescue, in exchange for providing support.[77][78]

Legal

Justice Blackmun, who authored the Roe decision, stood by the analytical framework he established in Roe throughout his career.[79] Despite his initial reluctance, he became the decision's chief champion and protector during his later years on the Court.[80] Liberal and feminist legal scholars have had various reactions to Roe, not always giving the decision unqualified support. One argument is that Justice Blackmun reached the correct result but went about it the wrong way.[81] Another is that the end achieved by Roe does not justify its means of judicial fiat.[82]

Justice John Paul Stevens, while agreeing with the decision, has suggested that it should have been more narrowly focused on the issue of privacy. According to Stevens, if the decision had avoided the trimester framework and simply stated that the right to privacy included a right to choose abortion, "it might have been much more acceptable" from a legal standpoint.[83] Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had, before joining the Court, criticized the decision for ending a nascent movement to liberalize abortion law through legislation.[84] Ginsburg has also faulted the Court's approach for being "about a doctor's freedom to practice his profession as he thinks best.... It wasn't woman-centered. It was physician-centered."[85] Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox wrote: "[Roe's] failure to confront the issue in principled terms leaves the opinion to read like a set of hospital rules and regulations.... Neither historian, nor layman, nor lawyer will be persuaded that all the prescriptions of Justice Blackmun are part of the Constitution."[86]

In a highly cited Yale Law Journal article published in the months after the decision,[8] the American legal scholar John Hart Ely strongly criticized Roe as a decision that was disconnected from American constitutional law.[87]

What is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers' thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation's governmental structure. ... The problem with Roe is not so much that it bungles the question it sets itself, but rather that it sets itself a question the Constitution has not made the Court's business. ... [Roe] is bad because it is bad constitutional law, or rather because it is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be.

— John Hart Ely (1973), "The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade", Yale Law Journal.[88]

Professor Laurence Tribe had similar thoughts: "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found."[89] Liberal law professors Alan Dershowitz,[90] Cass Sunstein,[91] and Kermit Roosevelt have also expressed disappointment with Roe v. Wade.[92]

Jeffrey Rosen[93] and Michael Kinsley[94] echo Ginsburg, arguing that a legislative movement would have been the correct way to build a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights. William Saletan wrote, "Blackmun's [Supreme Court] papers vindicate every indictment of Roe: invention, overreach, arbitrariness, textual indifference."[95] Benjamin Wittes has written that Roe "disenfranchised millions of conservatives on an issue about which they care deeply."[96] And Edward Lazarus, a former Blackmun clerk who "loved Roe's author like a grandfather," wrote: "As a matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe borders on the indefensible.... Justice Blackmun's opinion provides essentially no reasoning in support of its holding. And in the almost 30 years since Roe's announcement, no one has produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own terms."[97]

The assertion that the Supreme Court was making a legislative decision is often repeated by opponents of the ruling.[98] The "viability" criterion is still in effect, although the point of viability has changed as medical science has found ways to help premature babies survive.[99]

Public opinion

Americans have been equally divided on the issue; a May 2018 Gallup poll indicated that 48% of Americans described themselves as "pro-choice" and 48% described themselves as "pro-life". A July 2018 poll indicated that only 28% of Americans wanted the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade, while 64% did not want the ruling to be overturned.[100]

A Gallup poll conducted in May 2009 indicated that 53% of Americans believed that abortions should be legal under certain circumstances, 23% believed abortion should be legal under any circumstances, and 22% believed that abortion should be illegal in all circumstances. However, in this poll, more Americans referred to themselves as "Pro-Life" than "Pro-Choice" for the first time since the poll asked the question in 1995, with 51% identifying as "Pro-Life" and 42% identifying as "Pro-Choice".[101] Similarly, an April 2009 Pew Research Center poll showed a softening of support for legal abortion in all cases compared to the previous years of polling. People who said they support abortion in all or most cases dropped from 54% in 2008 to 46% in 2009.[102]

In contrast, an October 2007 Harris poll on Roe v. Wade asked the following question:

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that states laws which made it illegal for a woman to have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy were unconstitutional, and that the decision on whether a woman should have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy should be left to the woman and her doctor to decide. In general, do you favor or oppose this part of the U.S. Supreme Court decision making abortions up to three months of pregnancy legal?[103]

In reply, 56% of respondents indicated favour while 40% indicated opposition. The Harris organization concluded from this poll that "56 percent now favours the U.S. Supreme Court decision." Anti-abortion activists have disputed whether the Harris poll question is a valid measure of public opinion about Roe's overall decision, because the question focuses only on the first three months of pregnancy.[104][105] The Harris poll has tracked public opinion about Roe since 1973:[103][106]

Regarding the Roe decision as a whole, more Americans support it than support overturning it.[107] When pollsters describe various regulations that Roe prevents legislatures from enacting, support for Roe drops.[107][108]

Role in subsequent decisions and politics

Opposition to Roe on the bench grew when President Reagan, who supported legislative restrictions on abortion, began making federal judicial appointments in 1981. Reagan denied that there was any litmus test: "I have never given a litmus test to anyone that I have appointed to the bench…. I feel very strongly about those social issues, but I also place my confidence in the fact that the one thing that I do seek are judges that will interpret the law and not write the law. We've had too many examples in recent years of courts and judges legislating."[109]

In addition to White and Rehnquist, Reagan appointee Sandra Day O'Connor began dissenting from the Court's abortion cases, arguing in 1983 that the trimester-based analysis devised by the Roe Court was "unworkable."[110] Shortly before his retirement from the bench, Chief Justice Warren Burger suggested in 1986 that Roe be "reexamined";[111] the associate justice who filled Burger's place on the Court—Justice Antonin Scalia—vigorously opposed Roe. Concern about overturning Roe played a major role in the defeat of Robert Bork's nomination to the Court in 1987; the man eventually appointed to replace Roe-supporter Lewis Powell was Anthony Kennedy.

The Supreme Court of Canada used the rulings in both Roe and Doe v. Bolton as grounds to find Canada's federal law restricting access to abortions unconstitutional. That Canadian case, R. v. Morgentaler, was decided in 1988.[112]

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services

In a 5–4 decision in 1989's Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, Chief Justice Rehnquist, writing for the Court, declined to explicitly overrule Roe, because "none of the challenged provisions of the Missouri Act properly before us conflict with the Constitution."[113] In this case, the Court upheld several abortion restrictions, and modified the Roe trimester framework.[113]

In concurring opinions, O'Connor refused to reconsider Roe, and Justice Antonin Scalia criticized the Court and O'Connor for not overruling Roe.[113] Blackmun—author of the Roe decision—stated in his dissent that White, Kennedy and Rehnquist were "callous" and "deceptive," that they deserved to be charged with "cowardice and illegitimacy," and that their plurality opinion "foments disregard for the law."[113] White had recently opined that the majority reasoning in Roe v. Wade was "warped."[111]

Planned Parenthood v. Casey

During initial deliberations for Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), an initial majority of five Justices (Rehnquist, White, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas) were willing to effectively overturn Roe. Kennedy changed his mind after the initial conference,[114] and O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter joined Blackmun and Stevens to reaffirm the central holding of Roe,[115] saying, "Our law affords constitutional protection to personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing, and education. [...] These matters, involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, are central to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life."[116] Only Justice Blackmun would have retained Roe entirely and struck down all aspects of the statute at issue in Casey.[79]

Scalia's dissent acknowledged that abortion rights are of "great importance to many women", but asserted that it is not a liberty protected by the Constitution, because the Constitution does not mention it, and because longstanding traditions have permitted it to be legally proscribed. Scalia concluded: "[B]y foreclosing all democratic outlet for the deep passions this issue arouses, by banishing the issue from the political forum that gives all participants, even the losers, the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight, by continuing the imposition of a rigid national rule instead of allowing for regional differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies the anguish."[117]

Stenberg v. Carhart

During the 1990s, the state of Nebraska attempted to ban a certain second-trimester abortion procedure known as intact dilation and extraction (sometimes called partial birth abortion). The Nebraska ban allowed other second-trimester abortion procedures called dilation and evacuation abortions. Ginsburg (who replaced White) stated, "this law does not save any fetus from destruction, for it targets only 'a method of performing abortion'."[118] The Supreme Court struck down the Nebraska ban by a 5–4 vote in Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), citing a right to use the safest method of second trimester abortion.

Kennedy, who had co-authored the 5–4 Casey decision upholding Roe, was among the dissenters in Stenberg, writing that Nebraska had done nothing unconstitutional.[118] In his dissent, Kennedy described the second trimester abortion procedure that Nebraska was not seeking to prohibit, and thus argued that since this dilation and evacuation procedure remained available in Nebraska, the state was free to ban the other procedure sometimes called "partial birth abortion."[118]

The remaining three dissenters in Stenberg—Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas—disagreed again with Roe: "Although a State may permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do so."[119]

Gonzales v. Carhart

In 2003, Congress passed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act,[120] which led to a lawsuit in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart.[121] The Court had previously ruled in Stenberg v. Carhart that a state's ban on "partial birth abortion" was unconstitutional because such a ban did not have an exception for the health of the woman.[122] The membership of the Court changed after Stenberg, with John Roberts and Samuel Alito replacing Rehnquist and O'Connor, respectively.[123][124] The ban at issue in Gonzales v. Carhart was a federal statute, rather than a state statute as in the Stenberg case, but was otherwise nearly identical to Stenberg, replicating its vague description of partial-birth abortion and making no exception for the consideration of the woman's health.[122]

On April 18, 2007, the Supreme Court handed down a 5 to 4 decision upholding the constitutionality of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act.[124] Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, asserting that Congress was within its power to generally ban the procedure, although the Court left the door open for as-applied challenges.[citation needed] Kennedy's opinion did not reach the question of whether the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Stenberg v. Carhart remained valid, and instead the Court stated that the challenged statute remained consistent with those past decisions whether or not those decisions remained valid.[citation needed]

Chief Justice John Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito joined the majority. Justices Ginsburg, joined by Stevens, Souter, and Breyer, dissented,[124][123] contending that the ruling ignored Supreme Court abortion precedent, and also offering an equality-based justification for abortion precedent. Thomas filed a concurring opinion, joined by Scalia, contending that the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey should be reversed.[citation needed] They also noted that the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act may have exceeded the powers of Congress under the Commerce Clause but that the question was not raised before the court.[125]

Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt

In the case of Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt, the most significant abortion rights case before the Supreme Court since Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992,[126][127][128] the Supreme Court in a 5–3 decision on June 27, 2016, swept away forms of state restrictions on the way abortion clinics can function. The Texas legislature enacted in 2013 restrictions on the delivery of abortions services that created an undue burden for women seeking an abortion by requiring abortion doctors to have difficult-to-obtain "admitting privileges" at a local hospital and by requiring clinics to have costly hospital-grade facilities. The Court struck down these two provisions "facially" from the law at issue—that is, the very words of the provisions were invalid, no matter how they might be applied in any practical situation. According to the Supreme Court the task of judging whether a law puts an unconstitutional burden on a woman's right to abortion belongs with the courts and not the legislatures.[129]

Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization

Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization is a pending Supreme Court case to be heard in the 2021–22 term. It is a legal challenge to Mississippi's 2018 Gestational Age Act, which had banned abortions after 15 weeks with sole exceptions for medical emergencies or fetal abnormality. Federal courts had enjoined the state from enforcing the law after the state's only abortion clinic, Jackson Women's Health Organization, filed suit immediately after passage; the federal courts identified the law violated the 24-week point of viability established by Roe v. Wade. The Supreme Court - following the death of pro-abortion rights Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the appointment of anti-abortion rights Amy Coney Barrett in her place - certified the petition in May 2021, limited to the question of "Whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional", and raising the question if the Supreme Court may use the case to overturn all or part of Roe v. Wade.[130][131]

Activities of Norma McCorvey

Norma McCorvey became a member of the anti-abortion movement in 1995; she supported making abortion illegal until shortly before her death in 2017.[132] In 1998, she testified to Congress:

It was my pseudonym, Jane Roe, which had been used to create the "right" to abortion out of legal thin air. But Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee never told me that what I was signing would allow women to come up to me 15, 20 years later and say, "Thank you for allowing me to have my five or six abortions. Without you, it wouldn't have been possible." Sarah never mentioned women using abortions as a form of birth control. We talked about truly desperate and needy women, not women already wearing maternity clothes.[26]

As a party to the original litigation, she sought to reopen the case in U.S. District Court in Texas to have Roe v. Wade overturned. However, the Fifth Circuit decided that her case was moot, in McCorvey v. Hill.[133] In a concurring opinion, Judge Edith Jones agreed that McCorvey was raising legitimate questions about emotional and other harm suffered by women who have had abortions, about increased resources available for the care of unwanted children, and about new scientific understanding of fetal development. However, Jones said she was compelled to agree that the case was moot.[citation needed][134] On February 22, 2005, the Supreme Court refused to grant a writ of certiorari, and McCorvey's appeal ended.[citation needed]

In an interview shortly before her death, McCorvey stated that she had taken an anti-abortion position because she had been paid to do so and that her campaign against abortion had been an act. She also stated that it did not matter to her if women wanted to have an abortion and they should be free to choose.[77][78][135][136][137] Robert Schenck, a pastor and anti-abortion activist who helped entice McCorvey to claim she changed sides, stated that what they had done with her was "highly unethical" and he had "profound regret" over the matter.[138]

Activities of Sarah Weddington

After arguing before the Court in Roe v. Wade at the age of 26, Sarah Weddington went on to be a representative in the Texas House of Representatives for three terms.[139] Weddington has also had a long and successful career as General Counsel for the United States Department of Agriculture, Assistant to President Jimmy Carter, lecturer at Texas Wesleyan University, and speaker and adjunct professor at the University of Texas at Austin.[139] Sarah Weddington explained in a speech at the Institute for Educational Ethics in Oklahoma why she used the false rape charges all the way to the Supreme Court: “My conduct may not have been totally ethical. But I did it for what I thought were good reasons."[140] In 2005, she asked the Supreme Court to review the 1973 ruling, arguing that the case should be heard again due to new evidence about the harm the procedure inflicts on women, but the petition was denied.

Presidential positions

President Richard Nixon did not publicly comment about the decision.[141] In private conversation later revealed as part of the Nixon tapes, Nixon said, "There are times when an abortion is necessary,... ."[142][143] However, Nixon was also concerned that greater access to abortions would foster "permissiveness," and said that "it breaks the family."[142]

Generally, presidential opinion has been split between major party lines. The Roe decision was opposed by Presidents Gerald Ford,[144] Ronald Reagan,[145] and George W. Bush.[146] President George H.W. Bush also opposed Roe, though he had supported abortion rights earlier in his career.[147][148]

President Jimmy Carter supported legal abortion from an early point in his political career, in order to prevent birth defects and in other extreme cases; he encouraged the outcome in Roe and generally supported abortion rights.[149] Roe was also supported by President Bill Clinton.[150] President Barack Obama has taken the position that "Abortions should be legally available in accordance with Roe v. Wade."[151]

President Donald Trump has publicly opposed the decision, vowing to appoint anti-abortion justices to the Supreme Court.[152] Upon Justice Kennedy's retirement in 2018, Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to replace him, and he was confirmed by the Senate in October 2018. A central point of Kavanaugh's appointment hearings was his stance on Roe v. Wade, of which he said to Senator Susan Collins that he would not "overturn a long-established precedent if five current justices believed that it was wrongly decided".[153] Despite Kavanaugh's statement, there is concern that with the Supreme Court having a strong conservative majority, that Roe v. Wade will be overturned given an appropriate case to challenge it. Further concerns were raised following the May 2019 Supreme Court 5–4 decision along ideological lines in Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt. While the case had nothing to do with abortion rights, the decision overturned a previous 1979 decision from Nevada v. Hall without maintaining the stare decisis precedent, indicating the current Court makeup would be willing to apply the same to overturn Roe v. Wade.[154]

State laws regarding Roe

Several states have enacted so-called trigger laws that would take effect in the event that Roe v. Wade is overturned, with the effect of outlawing abortions on the state level. Those states include Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota and South Dakota.[155] Additionally, many states did not repeal pre-1973 statutes that criminalized abortion, and some of those statutes could again be in force if Roe were reversed.[156]

Other states have passed laws to maintain the legality of abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned. Those states include California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, and Washington.[155]

The Mississippi Legislature has attempted to make abortion unfeasible without having to overturn Roe v. Wade. The Mississippi law as of 2012 was being challenged in federal courts and was temporarily blocked.[157]

Alabama House Republicans passed a law on April 30, 2019 that will criminalize abortion if it goes into effect.[158] It offers only two exceptions: serious health risk to the mother or a lethal fetal anomaly. Alabama governor Kay Ivey signed the bill into law on May 14, primarily as a symbolic gesture in hopes of challenging Roe v. Wade in the Supreme Court.[159][160][161]

According to a 2019 study, if Roe v. Wade is reversed and abortion bans are implemented in trigger law states and states considered highly likely to ban abortion, the increases in travel distance are estimated to prevent 93,546 to 143,561 women from accessing abortion care.[162]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- ^ Mears, William; Franken, Bob (January 22, 2003). "30 years after ruling, ambiguity, anxiety surround abortion debate". CNN.

In all, the Roe and Doe rulings impacted laws in 46 states.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 72

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.29(a)(i).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 887.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.29(b)(i).

- ^ Dworkin, Roger (1996). Limits: The Role of the Law in Bioethical Decision Making. Indiana University Press. pp. 28–36. ISBN 978-0253330758.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenhouse 2005, pp. 135–36

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, pp. 892–95..

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, pp. 892–93.

- ^ Roe, 410 U.S. at 130.

- ^ Roe, 410 U.S. at 131–36, 143.

- ^ Cole, George; Frankowski, Stanislaw. Abortion and protection of the human fetus : legal problems in a cross-cultural perspective, p. 20 (1987): "By 1900 every state in the Union had an anti-abortion prohibition." Via Google Books. Retrieved (April 8, 2008).

- ^ Wilson, James, "Of the Natural Rights of Individuals Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine" (1790–1792): "In the contemplation of law, life begins when the infant is first able to stir in the womb." Also see Blackstone, William. Commentaries Archived February 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (1765): "Life ... begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother's womb."

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 92

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paltrow, Lynn M. (January 2013). "Roe v Wade and the New Jane Crow: Reproductive Rights in the Age of Mass Incarceration". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (1): 17–21. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301104. PMC 3518325. PMID 23153159.

- ^ Reagan, LJ (1997). When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States 1867–1973. University of California Press.[page needed]

- ^ "Rally Today Supports Wheeler". The Harvard Crimson. Cambridge, Mass. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ Nordheimer, Jon (December 4, 1971). "She's Fighting Conviction For Aborting Her Child". The New York Times. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ California Health & Safety Code § 25950 et seq.

- ^ See Karen Blumenthal, Jane Against the World: Roe v. Wade and the Fight for Reproductive Rights, Roaring Brook Press, 2020.

- ^ McCorvey, Norma and Meisler, Andy. I Am Roe: My Life, Roe V. Wade, and Freedom of Choice (Harper Collins 1994).

- ^ Friedman Goldstein, Leslie (1994). Contemporary Cases in Women's Rights. Madison: The University of Wisconsin. p. 15.

- ^ Rourke, Mary; Reyes, Emily Alpert (February 18, 2017). "Norma McCorvey, once-anonymous plaintiff in 'Roe vs. Wade,' dies at 69". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Richard Ostling. "A second religious conversion for 'Jane Roe' of Roe vs. Wade" Archived February 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (October 19, 1998): "She confessed that her tale of rape a decade before had been a lie; she was simply an unwed mother who later gave the child up for adoption."

- ^ Jump up to: a b McCorvey, Norma. Testimony to the Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution, Federalism and Property Rights (January 21, 1998), also quoted in the parliament of Western Australia (PDF) (May 20, 1998): "The affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court didn’t happen the way I said it did, pure and simple." Retrieved January 27, 2007

- ^ Noble, Kenneth B.; Times, Special To the New York (September 9, 1987). "Key Abortion Plaintiff Now Denies She Was Raped". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roe v. Wade, 314 F. Supp. 1217, 1221 (N.D. Tex. 1970) ("On the merits, plaintiffs argue as their principal contention that the Texas Abortion Laws must be declared unconstitutional because they deprive single women and married couple of their rights secured by the Ninth Amendment to choose whether to have children. We agree.").

- ^ O'Connor, Karen. Testimony before U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, "The Consequences of Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton", via archive.org (June 23, 2005). Retrieved January 30, 2007

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 77–79

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 80

- ^ Sant, Geoffrey. "8 horrible courtroom jokes and their ensuing legal calamities", Salon.com (July 27, 2013): "The title of Worst Joke in Legal History belongs to one of history's highest-profile cases. Defending Texas's abortion restrictions before the Supreme Court, attorney Mr. Jay Floyd decided to open oral argument with a sexist joke. Arguing against two female attorneys, Floyd begins: 'It's an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word.'" Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Malphurs 2010, p. 48

- ^ Garrow 1994, p. 526

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 81

- ^ Schwartz 1988, p. 103

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 81–88

- ^ Garrow 1994, p. 556

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 89

- ^ "Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113". LII / Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 93–95

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 96–97

- ^ Woodward, Bob. "The Abortion Papers Archived June 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine", Washington Post (January 22, 1989). Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ Michelman, Kate; Johnsen, Dawn (February 4, 1989). "The Abortion Papers (Op-Ed)". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenhouse 2005, p. 97

- ^ Kmiec, Douglas. "Testimony Before Subcommittee on the Constitution, Judiciary Committee, U.S. House of Representatives" (April 22, 1996), via the "Abortion Law Homepage". Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Abernathy, M. et al. (1993), Civil Liberties Under the Constitution. U. South Carolina, p. 4. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ Hames, Joanne Banker; Ekern, Yvonne (2012). Constitutional Law: Principles and Practice. Cengage Learning. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-285-40122-5.

- ^ Chemerinsky, Erwin (2003). Federal Jurisdiction. Introduction to Law (4th ed.). Aspen Publishers. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7355-2718-8.

- ^ Southern Pacific v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 219 U.S. 498 (1911).

- ^ Roe, 410 U.S. at 125; see also Schwartz 1988, pp. 108–09

- ^ Quoted in Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 887.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 887, quoting Roe, 410 U.S. at 153.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, pp. 887–88.

- ^ Quoted in Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 888.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 888, note 47.

- ^ Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 888, quoting Doe, 410 U.S. at 222 (White, J., dissenting).

- ^ Roe, 410 U.S. at 174–77 (Rehnquist, J., dissenting).

- ^ Currie, David (1994). "The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Second Century, 1888–1986". 2. University of Chicago Press: 470. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Rehnquist's legacy", The Economist (June 30, 2005).

- ^ Kommers, Donald P.; Finn, John E.; Jacobsohn, Gary J. (2004). American Constitutional Law: Essays, Cases, and Comparative Notes. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2687-7.

- ^ "Analysis | How America feels about abortion". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Koppelman, Andrew. "Forced Labor: A Thirteenth Amendment Defense of Abortion" Archived February 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Northwestern Law Review, Vol. 84, p. 480 (1990).

- ^ Jump up to: a b What Roe v. Wade Should Have Said; The Nation's Top Legal Experts Rewrite America's Most Controversial decision, Jack Balkin Ed. (NYU Press 2005). Retrieved January 26, 2007

- ^ Shimron, Yonat. "Democratic Gains Spur Abortion Foes into Action," The News & Observer (January 18, 2009): "The annual March for Life procession is already among Washington's largest rallies, drawing an estimated 200,000 people."

- ^ Harper, Jennifer. "a marchers lose attention," Washington Times (January 22, 2009): "the event has consistently drawn about 250,000 participants each year since 2003."

- ^ Johnston, Laura. "Cleveland's first March for Life anti-abortion event draws 200," The Plain Dealer (January 18, 2009): "the Washington March for Life…draws 200,000 annually on the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision."

- ^ "Youth Turnout Strong at US March for Life". Catholic.net. Zenit.org. January 25, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Portteus, Danielle (February 10, 2013). "Newport: 650,000 In March For Life". . MonroeNews. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ James F. Childress (1984). Bioethics Reporter. University Publications of America. p. 463. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

Roe v. Wade itself provided abortion rights with an unstable foundation.

- ^ Alex Locay (2008). Unveiling the Left. Xulon Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-60266-869-0. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

To justify their decision the Court made up a new "right", not found in the Constitution: the right to privacy. The founders of course never intended for such rights to exists, as we know privacy is limited in many ways.

- ^ Reagan, Ronald. Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation, (Nelson 1984): "If you don't know whether a body is alive or dead, you would never bury it. I think this consideration itself should be enough for all of us to insist on protecting the unborn." Retrieved January 26, 2007

- ^ Guttmacher Institute, "State Policies in Brief, An Overview of Abortion Laws (PDF)", published January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980).

- ^ Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973).

- ^ McCorvey, Norma, with Andy Meisler (1994). I Am Roe: My Life, Roe v. Wade, and Freedom of Choice. New York: Harper-Collins.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blake, Meredith (May 19, 2020). "The woman behind 'Roe vs. Wade' didn't change her mind on abortion. She was paid". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hesse, Monica (May 20, 2020). "'Jane Roe,' from Roe v. Wade, made a stunning deathbed confession. Now what?". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Casey, 505 U.S. at 930–34 (Blackmun, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) ("In sum, Roe's requirement of strict scrutiny as implemented through a trimester framework should not be disturbed.").

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 183–206, 250

- ^ Balkin, Jack. Bush v. "Gore and the Boundary Between Law and Politics" Archived February 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 110 Yale Law Journal 1407 (2001): "Liberal and feminist legal scholars have spent decades showing that the result was correct even if Justice Blackmun's opinion seems to have been taken from the Court's Cubist period."

- ^ Cohen, Richard. "Support Choice, Not Roe", Washington Post, (October 19, 2005): "If the best we can say for it is that the end justifies the means, then we have not only lost the argument—but a bit of our soul as well." Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (September 23, 2007). "The Dissenter". The New York Times Magazine. Rosen notes that Stevens is "the oldest and arguably most liberal justice."

- ^ Ginsburg, Ruth. "Some Thoughts on Autonomy and Equality in Relation to Roe v. Wade", 63 North Carolina Law Review 375 (1985): "The political process was moving in the early 1970s, not swiftly enough for advocates of quick, complete change, but majoritarian institutions were listening and acting. Heavy-handed judicial intervention was difficult to justify and appears to have provoked, not resolved, conflict." Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Bullington, Jonathan (May 11, 2013). "Justice Ginsburg: Roe v. Wade not 'woman-centered'". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Cox, Archibald. The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government, 113–14 (Oxford U. Press 1976), via Google Books. Retrieved January 26, 2007. Stuart Taylor has argued that "Roe v. Wade was sort of conjured up out of very general phrases and was recorded, even by most liberal scholars like Archibald Cox at the time, John Harvey Link—just to name two Harvard scholars—as kind of made-up constitutional law." See Stuart Taylor Jr., Online News Hour, PBS July 13, 2000.

- ^ Ely, John Hart. "The Wages of Crying Wolf Archived 2007-06-25 at the Wayback Machine", 82 Yale Law Journal 920 (1973). Retrieved January 23, 2007. Professor Ely "supported the availability of abortion as a matter of policy." See Liptak, Adam. "John Hart Ely, a Constitutional Scholar, Is Dead at 64", The New York Times (October 27, 2003). Ely is generally regarded as having been a "liberal constitutional scholar." Perry, Michael (1999). We the People: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Supreme Court at Google Books

- ^ John Hart Ely (1973), "The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade", Yale Law Journal, 82 (5): 920–49, doi:10.2307/795536, JSTOR 795536, PMID 11663374, quoted in Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.3.3.1, p. 856.

- ^ Tribe, Laurence (1973). "The Supreme Court, 1972 Term – Foreword: Toward a Model of Roles in the Due Process of Life and Law". Harvard Law Review. 87 (1): 1–314. doi:10.2307/1339866. JSTOR 1339866. PMID 11663596. Quoted in Morgan, Richard Gregory (1979). "Roe v. Wade and the Lesson of the Pre-Roe Case Law". Michigan Law Review. 77 (7): 1724–48. doi:10.2307/1288040. JSTOR 1288040. PMID 10245969.

- ^ Dershowitz, Alan. Supreme Injustice: How the High Court Hijacked Election 2000 (Oxford U. Press 2001): "Judges have no special competence, qualifications, or mandate to decide between equally compelling moral claims (as in the abortion controversy)...." quoted by Green, "Bushed and Gored: A Brief Review of Initial Literature", in The Final Arbiter: The Consequences of Bush V. Gore for Law And Politics, ed. Banks C, Cohen D & Green J., editors, p. 14 (SUNY Press 2005), via Google Books. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Sunstein, Cass. Quoted by McGuire, New York Sun (November 15, 2005): "What I think is that it just doesn't have the stable status of Brown or Miranda because it's been under internal and external assault pretty much from the beginning....As a constitutional matter, I think Roe was way overreached." Retrieved January 23, 2007. Sunstein is a "liberal constitutional scholar." See Herman, Eric. "Former U of C law prof on everyone's short court list", Chicago Sun-Times (2005-07-11).[dead link]

- ^ Roosevelt, Kermit. "Shaky Basis for a Constitutional ‘Right’", Washington Post, (January 22, 2003): "[I]t is time to admit in public that, as an example of the practice of constitutional opinion writing, Roe is a serious disappointment. You will be hard-pressed to find a constitutional law professor, even among those who support the idea of constitutional protection for the right to choose, who will embrace the opinion itself rather than the result….This is not surprising. As constitutional argument, Roe is barely coherent. The court pulled its fundamental right to choose more or less from the constitutional ether. It supported that right via a lengthy, but purposeless, cross-cultural historical review of abortion restrictions and a tidy but irrelevant refutation of the straw-man argument that a fetus is a constitutional ‘person’ entitled to the protection of the 14th Amendment....By declaring an inviolable fundamental right to abortion, Roe short-circuited the democratic deliberation that is the most reliable method of deciding questions of competing values." Retrieved January 23, 2007. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (February 24, 2003). "Why We'd Be Better off Without Roe: Worst Choice". The New Republic. Archived from the original on March 9, 2003. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

In short, 30 years later, it seems increasingly clear that this pro-choice magazine was correct in 1973 when it criticized Roe on constitutional grounds. Its overturning would be the best thing that could happen to the federal judiciary, the pro-choice movement, and the moderate majority of the American people.

- See also: Rosen, Jeffrey (June 2006). "The Day After Roe". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Kinsley, Michael. "Bad choice", The New Republic (June 13, 2004): "Against all odds (and, I'm afraid, against all logic), the basic holding of Roe v. Wade is secure in the Supreme Court....[A] freedom of choice law would guarantee abortion rights the correct way, democratically, rather than by constitutional origami." Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Saletan, William. "Unbecoming Justice Blackmun", Legal Affairs, May/June 2005. Retrieved January 23, 2007. Saletan is a self-described liberal. See Saletan, William. "Rights and Wrongs: Liberals, progressives, and biotechnology", Slate (July 13, 2007).

- ^ Wittes, Benjamin. "Letting Go of Roe", The Atlantic Monthly, Jan/Feb 2005. Retrieved January 23, 2007. Wittes also said, "I generally favor permissive abortion laws." He has elsewhere noted, "In their quieter moments, many liberal scholars recognize that the decision is a mess." See Wittes, Benjamin. "A Little Less Conversation", The New Republic November 29, 2007

- ^ Lazarus, Edward. "The Lingering Problems with Roe v. Wade, and Why the Recent Senate Hearings on Michael McConnell's Nomination Only Underlined Them", Findlaw's Writ (October 3, 2002). Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Forsythe, Clarke (2013). Abuse of Discretion: The Inside Story of Roe v. Wade. Encounter Books. p. 496. ISBN 978-1594036927.

- ^ Stith, Irene. Abortion Procedures, CRS Report for Congress (PDF) (November 17, 1997). Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ "Gallup: Abortion". Gallup poll. June 22, 2007.

- ^ Saad, Lydia. More Americans "Pro-Life" Than "Pro-Choice" for First Time, Gallup (May 15, 2009).

- ^ "Public Takes Conservative Turn on Gun Control, Abortion Americans Now Divided Over Both Issues", Pew Research Center (April 30, 2009).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris Interactive, (November 9, 2007). "Support for Roe v. Wade Increases Significantly, Reaches Highest Level in Nine Years Archived January 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ Franz, Wanda. "The Continuing Confusion About Roe v. Wade" Archived May 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, NRL News (June 2007).

- ^ Adamek, Raymond. "Abortion Polls", Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 411–13. Dr. Adamek is pro-life. Dr Raymond J Adamek, PhD Archived February 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Pro-Life Science and Technology Symposium.

- ^ Harris Interactive. 'U.S. Attitudes Toward Roe v. Wade". The Wall Street Journal Online, (May 4, 2006). Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ayres McHenry Poll Results on Roe v. Wade Archived October 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine via Angus Reid Global Monitor (2007).

- ^ Gallagher, Maggie. "Pro-Life Voters are Crucial Component of Electability", Realclearpolitics.com (May 23, 2007).

- ^ Reagan, Ronald. Interview With Eleanor Clift, Jack Nelson, and Joel Havemann of the Los Angeles Times (June 23, 1986). Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health, 462 U.S. 416 (1983).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986).

- ^ R. v. Morgentaler Archived October 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine 1 S.C.R. 30 (1988).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989).

- ^ Totenberg, Nina (March 4, 2004). "Documents Reveal Battle to Preserve 'Roe'; Court Nearly Reversed Abortion Ruling, Blackmun Papers Show". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 203–06

- ^ Casey, 505 U.S. at 851.

- ^ Casey, 505 U.S. at 1002 (Scalia, J., dissenting).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914, 958–59 (2000) ("The fetus, in many cases, dies just as a human adult or child would: It bleeds to death as it is torn from limb from limb. The fetus can be alive at the beginning of the dismemberment process and can survive for a time while its limbs are being torn off.").

- ^ O'Neill, Nicholas K. F.; O'Neill, Nick; Rice, Simon; Douglas, Roger (2004). Retreat from Injustice: Human Rights Law in Australia. Federation Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-86287-414-5.

- ^ "S.3 – Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003". Congress.gov. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (November 7, 2006). "'Late Term' Vs. 'Partial Birth'". CBS News. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nelson, Erin (2013). Law, Policy and Reproductive Autonomy. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-78225-155-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mezey, Susan Gluck (2017). Stooksbury, Kara E.; Scheb, John M., II; Stephens, Otis H., Jr (eds.). Encyclopedia of American Civil Rights and Liberties (Revised and Expanded Edition, 2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4408-4110-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stout, David (April 18, 2007). "Supreme Court Upholds Ban on Abortion Procedure". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Greely, Henry T. (2016). The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction. Harvard University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-674-72896-7.

- ^ Green, Emma (November 13, 2015). "A New Supreme Court Challenge: The Erosion of Abortion Access in Texas". Atlantic. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Hurley, Lawrence (June 28, 2016). "Supreme Court firmly backs abortion rights, tosses Texas law". Reuters. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Ariane de Vogue, Tal Kopan and Dan Berman (June 27, 2015). "Supreme Court strikes down Texas abortion access law". CNN. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Denniston, Lyle (June 27, 2016). "Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt – Opinion analysis: Abortion rights reemerge strongly". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Caroline; de Vogue, Ariane (May 17, 2021). "Supreme Court takes up major abortion case next term that could limit Roe v. Wade". CNN. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Sherman, Mark (May 17, 2021). "Supreme Court to weigh rollback of abortion rights". Associated Press. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Roe v Wade: Woman in US abortion legal test case dies". bbc.co.uk. February 18, 2017.

- ^ McCorvey v. Hill, 385 F.3d 846 (5th Cir. 2004).

- ^ Adams, Andrew (2004). "Aborting Roe: Jane Roe Questions the Viability of Roe v. Wade". Tex. Rev. L. & Pol.

- ^ Porterfield, Carlie (May 19, 2020). "'Roe Vs. Wade' Plaintiff Was Paid To Switch Sides In Abortion Fight, Documentary Reveals". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Serjeant, Jill (May 20, 2020). "Plaintiff in Roe v. Wade U.S. abortion case says she was paid to switch sides". www.reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Goldberg, Michelle (May 22, 2020). "Jane Roe's Pro-Life Conversion Was a Con – Norma McCorvey makes a shocking deathbed confession". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Lozano, Alicia Victoria. "Anti-abortion rights movement paid 'Jane Roe' thousands to switch sides, documentary reveals" NBC News (May 19, 2020).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Valerie Lapinski, Winning Roe v. Wade: Q&A with Sarah Weddington, Time (January 22, 2013), available at http://nation.time.com/2013/01/22/winning-roe-v-wade-qa-with-sarah-weddington/.

- ^ Tulsa World 24-V-93

- ^ Reeves, Richard (2001). President Nixon: Alone in the White House (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 563. ISBN 978-0-684-80231-2.

The President did not comment directly on the decision.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Savage, Charlie (June 23, 2009). "On Nixon Tapes, Ambivalence Over Abortion, Not Watergate". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ Harnden, Toby. "President Richard Nixon Said it Was 'Necessary' to Abort Mixed-Race Babies, Tapes Reveal," The Daily Telegraph (June 24, 2009).

- ^ Ford, Gerald. Letter to the Archbishop of Cincinnati, published online by The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara: University of California Press (September 10, 1976).

- ^ Reagan, Ronald. Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation (Nelson 1984).

- ^ Kornblut, Anne E. (January 22, 2000). "Bush Tells Addicts He Can Identify". Boston Globe. p. A12.

- ^ Fritz, Sara (August 18, 1992). "'92 Republican Convention: Rigid Anti-Abortion Platform Plank OKd Policy". Los Angeles Times.

President George Bush supported abortion rights until 1980, when he switched sides after Ronald Reagan picked Bush as his running mate.

- ^ Bush, George Herbert Walker.Remarks to Participants in the March for Life Rally (January 23, 1989): "I think the Supreme Court's decision in Roe versus Wade was wrong and should be overturned."

- ^ Carter, James Earl. Larry King Live, CNN, Interview With Jimmy Carter (February 1, 2006). Also see Bourne, Peter, Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Postpresidency: "Early in his term as governor, Carter had strongly supported family planning programs including abortion in order to save the life of a woman, birth defects, or in other extreme circumstances. Years later, he had written the foreword to a book, Women in Need, that favored a woman's right to abortion. He had given private encouragement to the plaintiffs in a lawsuit, Doe v. Bolton, filed against the state of Georgia to overturn its archaic abortion laws."

- ^ Clinton, Bill. My Life, p. 229 (Knopf 2004).

- ^ Obama, Barack. "1998 Illinois State Legislative National Political Awareness Test", Project Vote Smart, via archive.org. Retrieved on January 21, 2007.

- ^ Foran, Clare (June 29, 2018). "The plan to overturn Roe v. Wade at the Supreme Court is already in motion". CNN. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Green, Emma (October 10, 2018). "Susan Collins Gambles With the Future of Roe v. Wade". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Litman, Leah (May 13, 2019). "Supreme Court Liberals Raise Alarm Bells About Roe v. Wade". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vestal, Christine. "States probe limits of abortion policy", Stateline.org (June 11, 2007).

- ^ Marcus, Frances Frank. "Louisiana Moves Against Abortion", The New York Times (July 8, 1989).

- ^ LZ Granderson "Mississippi's end run around abortion", CNN (July 12, 2012).

- ^ Stracqualursi, Veronica (May 1, 2019). "Alabama House passes bill that would make abortion a felony". CNN. Retrieved May 2, 2019.