Rogerian argument

Rogerian argument (or Rogerian rhetoric) is a rhetorical and conflict resolution strategy based on empathizing with others, seeking common ground and mutual understanding and learning, while avoiding the negative effects of extreme attitude polarization.[1][2][3] The term Rogerian refers to the psychologist Carl Rogers, whose client-centered therapy has also been called Rogerian therapy. Since 1970, rhetoricians have applied the ideas of Rogers—with contributions by Anatol Rapoport—to rhetoric and argumentation, producing Rogerian argument.

A key principle of Rogerian argument is that, instead of advocating one's own position and trying to refute the other's position, one tries to state the other's position with as much care as one would have stated one's own position, emphasizing what is strong or valid in the other's argument.[4] To this principle, Rapoport added other principles that are sometimes called "Rapoport's rules". Rhetoricians have designed various methods for applying these Rogerian rhetorical principles in practice.

Several scholars have criticized how Rogerian argument is taught. Already in the 1960s Rapoport had noted some of the limitations of Rogerian argument, and other scholars identified other limitations in the following decades. For example, they concluded that Rogerian argument is less likely to be appropriate or effective when communicating with violent or discriminatory people or institutions, in situations of social exclusion or extreme power inequality, or in judicial settings that use formal adversarial procedures.

Some empirical research has tested role reversal and found that its effectiveness depends on the issue and situation.

Origin[]

In the study and teaching of rhetoric and argumentation, the term Rogerian argument was popularized in the 1970s and 1980s[6][7] by the 1970 textbook Rhetoric: Discovery and Change[8] by the University of Michigan professors Richard E. Young, Alton L. Becker, and Kenneth L. Pike. They borrowed the term Rogerian and related ideas from the polymath Anatol Rapoport,[6][7] who was working, and doing peace activism, at the same university.[9] The University of Texas at Austin professor Maxine Hairston then spread Rogerian argument through publications such as her textbook A Contemporary Rhetoric,[10] and other authors published book chapters and scholarly articles on the subject.

Rapoport's three ways of changing people[]

Young, Becker, and Pike's 1970 textbook Rhetoric: Discovery and Change followed Rapoport's 1960 book Fights, Games, and Debates[11] in describing three ways of changing people that could be applied in debates: the Pavlovian strategy, the Freudian strategy, and the Rogerian strategy.[12] Rapoport noted that these three strategies correspond to three methods of psychotherapy—three ways of trying to change someone's mind and behavior.[13] Young, Becker, and Pike said that the strategies correspond to three big assumptions about humanity, which they called three "images of man".[12]

Pavlovian strategy[]

The Pavlovian strategy represents people "as a bundle of habits that can be shaped and controlled" by punishments and rewards.[14] This strategy changes people by punishing undesired habits and rewarding desired habits.[15] Some examples of Pavlovian techniques in the real world are behaviorist teaching machines,[14] training of simple skills,[16] and brainwashing, which Rapoport called "another name for training".[17] Some fictional examples cited by Rapoport are the inquisitors in Shaw's Saint Joan, in Koestler's Darkness at Noon, and in Orwell's 1984.[18] The Pavlovian strategy can be benign or malign,[17] but a "fundamental limitation" of the strategy is that the user of it must have complete control over the rewards and punishments used to change someone's mind and behavior, and someone in a conflict is unlikely to submit to such control by a perceived opponent, except under draconian conditions such as imprisonment.[17]

Freudian strategy[]

The Freudian strategy represents people as consciously espousing beliefs that are produced by unconscious or hidden motives that are unknown to them; changing people's beliefs—and changing any behaviors that are caused by those beliefs—requires revealing the hidden motives.[14][19] Rapoport considered this strategy to be at the core of Freudian psychoanalysis but also to be present in any other kind of analysis that aims to change people's minds or behaviors by explaining how their beliefs or discourse are a product of hidden motives or mechanisms.[19] Rapoport mentioned his own teaching as one example of this strategy, in situations where his students' resistance to new knowledge was dissolved by the teacher pointing out how the students' opposing preconceptions were caused by the students' memories of prior experiences that were illusory or irrelevant to the new knowledge.[14][20] Another of Rapoport's examples was a certain kind of Marxist class analysis, used repeatedly by Lenin, in which the ideals of liberal intellectuals are "explained away" by Marxists as nothing more than a rationalization of the liberals' unconscious motive to preserve their social class position in a capitalist economic system.[21] Such "explaining away" or "debunking" of people's beliefs and behaviors may work, Rapoport said, when there is "a complete trust placed by the target of persuasion in the persuader", as sometimes occurs in teaching and psychotherapy.[15] But such complete trust is unlikely in most conflict situations, and the strategy can often be turned back against someone who is trying to use it: "It has been used by anti-Communists on the Communists (clothed in Freudian terminology) as well as by the Communists on the anti-Communists (clothed in Marxist terminology)."[22]

Rogerian strategy[]

The Rogerian strategy represents people as usually trying to protect themselves from what they perceive to be threatening.[15][23] This strategy invites people to consider the possibility of changing by removing the threat that the change implies. Rapoport noted that Freudian psychoanalysts often diagnose people's defenses against what is perceived to be threatening, since such defenses can be among the hidden motives that the Freudian strategy tries to uncover.[15] But the Freudian strategy of changing someone's mind and behavior by explaining hidden motives will not work whenever a person perceives the explanation itself to be threatening in some way, as is likely to happen when the explanation comes from a perceived opponent in a conflict.[24] There are many ways that someone's statements could be perceived, consciously or unconsciously, as threatening: for example, the other may perceive some statement as being aggressive to some degree, or even destructive of the other's entire worldview.[24] To remove the threat requires trying not to impose one's own explanation or argument on the other in any way.[25] Instead, the Rogerian strategy starts by "providing deep understanding and acceptance of the attitudes consciously held at this moment" by the other,[26] and this attitude is not a subtle trick used to try to control or persuade the other; in the words of Rogers, "To be effective, it must be genuine."[26] Rapoport suggested three principles that characterize the Rogerian strategy: listening and making the other feel understood, finding merit in the other's position, and increasing the perception of similarity between people.[27]

Rogers on communication[]

A work by Carl Rogers that was especially influential in the formulation of Rogerian argument was his 1951 paper "Communication: Its Blocking and Its Facilitation",[28] published in the same year as his book Client-Centered Therapy.[29] Rogers began the paper by arguing that psychotherapy and communication are much more closely related than people might suspect, because psychotherapy is all about remedying failures in communication—where communication is defined as a process that happens both within a person as well as between people.[30] For Rogers, the troubling conflict between a person's conscious and unconscious convictions that may require psychotherapy is similar to the troubling conflict between two people's convictions that may require mediation.[31] Rogers proposed that effective psychotherapy always helps establish good communication, and good communication is always therapeutic.[30] Rogers said that the major barrier to good communication between people is one's tendency to evaluate what other people say from within one's own usual point of view and way of thinking and feeling, instead of trying to understand what they say from within their point of view and way of thinking and feeling; the result is that people talk past each other instead of think together.[32] If one accurately and sympathetically understands how others think and feel from inside, and if one communicates this understanding to them, then it frees others from feeling a need to defend themselves, and it changes one's own thinking and feeling to some degree, said Rogers.[33] And if two people or two groups of people can do this for each other, it allows them "to come closer and closer to the objective truth involved in the relationship" and creates mutual good communication so that "some type of agreement becomes much more possible".[34]

One idea that Rogers emphasized several times in his 1951 paper that is not mentioned in textbook treatments of Rogerian argument is third-party intervention.[35] Rogers suggested that a neutral third party, instead of the parties to the conflict themselves, could in some cases present one party's sympathetic understanding of the other to the other.[36]

Rogerian argument is an application of Rogers' ideas about communication, taught by rhetoric teachers who were inspired by Rapoport,[6][7] but Rogers' ideas about communication have also been applied somewhat differently by many others: for example, Marshall Rosenberg created nonviolent communication, a process of conflict resolution and nonviolent living, after studying and working with Rogers,[37] and other writing teachers used some of Rogers' ideas in developing expressivist theories of writing.[38]

Relation to classical rhetoric[]

There are different opinions about whether Rogerian rhetoric is like or unlike classical rhetoric from ancient Greece and Rome.[39]

Young, Becker, and Pike said that classical rhetoric and Rapoport's Pavlovian strategy and Freudian strategy all share the common goal of controlling or persuading someone else, but the Rogerian strategy has different assumptions about humanity and a different goal.[40] In Young, Becker, and Pike's view, the goal of Rogerian rhetoric is to remove the obstacles—especially the sense of threat—to cooperative communication, mutual understanding, and mutual intellectual growth.[23] They considered this goal to be a new alternative to classical rhetoric.[41] They also said that classical rhetoric is used both in dyadic situations—when two parties are trying to understand and change each other—and in triadic situations—when one party is responding to an opponent but is trying to influence a third party such as an arbitrator or jury or public opinion—but Rogerian rhetoric is specially intended for certain dyadic situations, not for triadic situations.[42]

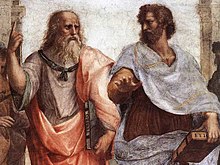

English professor Andrea Lunsford, responding to Young, Becker, and Pike in a 1979 article, argued that the three principles of Rogerian strategy that they borrowed from Rapoport could be found in various parts of Aristotle's writings, and so were already in the classical tradition.[43] She pointed to Book I of Aristotle's Rhetoric where he said that one must be able to understand and argue both sides of an issue,[43] and to his discussions of friendship and of the enthymeme in Book II,[44] and to similar passages in his Topics.[45] She also saw some similarity to Plato's Phaedrus.[46] Other scholars have also found resonances between Rogerian and Platonic "rhetorics of dialogue".[47]

English professor Paul G. Bator argued in 1980 that Rogerian argument is more different from Aristotle's rhetoric than Lunsford had concluded.[48] Among the differences he noted: the Aristotelian rhetor (orator) portrays a certain character (ethos) to try to persuade the audience to the rhetor's point of view, whereas the Rogerian rhetor listens not to "ingratiate herself" but to genuinely understand and accept the other's point of view and to communicate that understanding and acceptance;[49] the Aristotelian rhetor has a predetermined intention to win over the opposition, whereas the Rogerian rhetor has an open-ended intention to facilitate change through mutual understanding and cooperation;[50] the Aristotelian rhetor may or may not explicitly acknowledge the opponent's position, whereas for the Rogerian rhetor an accurate and sympathetic statement of the other's position is essential.[50]

Professor of communication Douglas Brent said that Rogerian rhetoric is not the captatio benevolentiae (securing of good will) taught by Cicero and later by medieval rhetoricians.[51] Brent said that superficially confusing the Rogerian strategy with such ingratiation overlooks "the therapeutic roots of Rogers' philosophy", rhetoric's power to heal both speakers and listeners, and the importance of "genuine grounds of shared understanding, not just as a precursor to an 'effective' argument, but as a means of engaging in effective knowledge-making".[51]

Rapoport's rules[]

By the end of the 1960s, the term Rapoport debate[52][53] was used to refer to what Anatol Rapoport called ethical debate,[54] which is debate guided by Rapoport's Rogerian strategy. Philosopher Daniel Dennett, in his 2013 book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, called these principles Rapoport's rules of debate,[55] a term that other authors have since adopted.[56][57]

Rapoport proposed three main principles of ethical debate:[27][58][59][60]

- Listening and making the other feel understood has two parts: First, listening by example, which Rapoport attributed to S. I. Hayakawa, is listening to others so that they will be willing to listen as well.[58][59] Second, role reversal, which Rapoport attributed to Carl Rogers,[54] is listening carefully and empathetically enough to be able to state the other's position to the other's satisfaction, and vice versa.[58][59] Rapoport called this principle "conveying to the opponent that he has been heard and understood", and he noted that it is the main component of Rogers's nondirective client-centered therapy.[61]

- Finding some merit in the other's position, or what Rapoport called "delineating the region of validity of the opponent's stand", is the opposite of the usual intent in a debate, the usual intent being to refute or invalidate the other's position.[62] Most opinions can be partly justified in some circumstances from some perspective, so the aim should be to identify what is conditionally justifiable in the other's position and to give examples that support it.[58][62] It is implied, but not stated, that the other's position is not strong or valid in some other circumstances outside of the identified "region of validity".[58][62] This second principle reinforces the first principle by communicating to the other in a new way that the other has been heard and understood.[62][63] It also implies some agreement and common ground between the two positions, while contributing toward a better understanding of the area of disagreement.[64] Furthermore, acknowledging that there is some merit in the other's position may make one more willing to re-examine one's own position and perhaps find some part of it that is not strong or valid in some way,[59] which ultimately may lead "away from the primitive level of verbal opposition to deeper levels where searching investigation is encouraged",[65] perhaps leading to larger field of view with a larger region of validity.[66]

- Increasing perceived similarity is a deepening of the sense of common humanity between self and other, a sense of shared strengths and flaws.[67] Like the second principle, this third principle is the opposite of what is usual in a debate, the usual perception being that the other is different in an inferior way, such as more "stupid or rigid or dishonest or ruthless".[67] Instead of emphasizing the uniqueness of the flaws of the other, "one seeks within oneself the clearly perceived shortcomings of the opponent",[67] and instead of emphasizing the uniqueness of one's own strengths (such as intelligence, honesty, and conscientiousness), one asks how the other shares such qualities to some degree.[67] Rapoport considered this "assumption of similarity" to be "the psychological set [or mindset] conducive to conflict resolution".[67] An obstacle that prevents people from making the assumption of similarity is the notion "that such an assumption is evidence of [a debater's] professional incompetence".[68] But that notion is counterproductive, Rapoport argued, because the assumption of similarity, together with the other two principles, is likely to remove obstacles to cooperation and to successful debate outcomes.[69] Rapoport said: "The outcome depends on the occurrence of one crucial insight: we are all in the same boat."[70]

Dennett's version[]

Daniel Dennett's version of Rapoport's rules, which Dennett considered to be "somewhat more portable and versatile", is:

- "You should attempt to re-express your target's position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, 'Thanks, I wish I'd thought of putting it that way.'"[71]

- "You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement)."[72]

- "You should mention anything you have learned from your target."[72]

- "Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism."[72]

Dennett's other advice, in his presentation of Rapoport's rules, had more of an adversarial outlook than a Rogerian one: he said that some people "don't deserve such respectful attention" and that he found it to "be sheer joy to skewer and roast" such people.[72] In contrast to Rogers' attitude of consistently "providing deep understanding and acceptance of the attitudes consciously held at this moment" by the other,[26] Dennett advised: "If there are obvious contradictions in the opponent's case, then of course you should point them out, forcefully. If there are somewhat hidden contradictions, you should carefully expose them to view—and then dump on them."[71] Although Dennett personally found Rapoport's rules to be "something of a struggle" to practice,[72] he called the rules a strong antidote for the tendency to uncharitably caricature someone else's position in a debate.[71]

In a summary of Dennett's version of Rapoport's rules, Peter Boghossian and James A. Lindsay pointed out that an important part of how Rapoport's rules work is by modeling prosocial behavior: one party demonstrates respect and intellectual openness so that the other party can emulate those characteristics, which would be less likely to occur in intensely adversarial conditions.[73]

Relation to game theory[]

English professor Michael Austin, in his 2019 book We Must Not Be Enemies, pointed out the connection between Rapoport's three principles of ethical debate, published in 1960, and Rapoport's tit-for-tat algorithm that won political scientist Robert Axelrod's repeated prisoner's dilemma computer tournaments around 1980.[74] Austin summarized Axelrod's conclusion that Rapoport's tit-for-tat algorithm won those tournaments because it was (in a technical sense) nice, forgiving, not envious, and absolutely predictable.[75] With these characteristics, tit-for-tat elicited mutually rewarding outcomes more than any of the competing algorithms did over many automated repetitions of the prisoner's dilemma game.[76]

In the 1950s, R. Duncan Luce had introduced Rapoport to the prisoner's dilemma game,[77] a kind of non-zero-sum game. Rapoport proceeded to publish a landmark 1965 book of empirical psychological research using the game, followed by another book in 1976 on empirical research about seventy-eight 2 × 2 two-person non-zero-sum games.[78] All this research had prepared Rapoport to understand, perhaps better than anyone else at the time, the best ways to win non-zero-sum games such as Axelrod's tournaments.[76]

Rapoport himself, in his 1960 discussion of the Rogerian strategy in Fights, Games, and Debates, connected the ethics of debate to non-zero-sum games.[79] Rapoport distinguished three hierarchical levels of conflict:

- fights are unthinking and persistent aggression against an opponent "motivated only by mutual animosity or mutual fear";[80]

- games are attempts "to outwit the opponent" by achieving the best possible outcome within certain shared rules;[81]

- debates are verbal conflicts about the convictions of the opponents, each of whom aims "to convince the opponent".[82]

Rapoport pointed out "that a rigorous examination of game-like conflict leads inevitably" to the examination of debates, because "strictly rigorous game theory when extrapolated to cover other than two-person zero-sum games" requires consideration of issues such as "communication theory, psychology, even ethics" that are beyond simple game-like rules.[83] He also suggested that the international affairs experts of the time were facing situations analogous to the prisoner's dilemma, but the experts often appeared incapable of taking actions, such as those recommended by Rapoport's three principles of ethical debate, that would allow the opponents to reach a mutually advantageous outcome.[84]

Austin said that the characteristics that Rapoport programmed into the tit-for-tat algorithm are similar to Rapoport's three principles of ethical debate: both tit-for-tat and Rapoport's rules of debate are guidelines for producing a beneficial outcome in certain "non-zero-sum" situations.[85] Both invite the other to reciprocate with cooperative behavior, creating an environment that makes cooperation and mutuality more profitable in the long run than antagonism and unilaterally trying to beat the opponent.[56]

In practice[]

In informal oral communication[]

In informal oral communication, Rogerian argument must be flexible because others can interject and show that one has failed to state their position and situation adequately, and then one must modify one's previous statements before continuing, resulting in an unpredictable sequence of conversation that is guided by the general principles of Rogerian strategy.[4]

Carl Rogers himself was primarily interested in spontaneous oral communication,[86] and Douglas Brent considered the "native" mode of Rogerian communication to be mutual exploration of an issue through face-to-face oral communication.[51] Whenever Brent taught the Rogerian attitude, he recommended to his students that before trying to write in a Rogerian way, they should first "practice on real, present people in a context more like the original therapeutic situations for which Rogerian principles were originally designed".[51]

In formal written communication[]

In formal written communication that addresses the reader, the use of Rogerian argument requires sufficient knowledge of the audience, through prior acquaintance or audience analysis, to be able to present the reader's perspective accurately and respond to it appropriately.[3] Since formal written communication lacks the immediate feedback from the other and the unpredictable sequence found in oral communication, and can use a more predictable approach, Young, Becker, and Pike proposed four phases that a writer could use to construct a written Rogerian argument:[87][88]

- "An introduction to the problem and a demonstration that the opponent's position is understood."[87]

- "A statement of the contexts in which the opponent's position may be valid."[87]

- "A statement of the writer's position, including the contexts in which it is valid."[87]

- "A statement of how the opponent's position would benefit if he were to adopt elements of the writer's position. If the writer can show that the positions complement each other, that each supplies what the other lacks, so much the better."[87]

The first two of Young, Becker, and Pike's four phases of written Rogerian argument are based on the first two of Rapoport's three principles of ethical debate.[87] The third of Rapoport's principles—increasing the perceived similarity between self and other—is a principle that Young, Becker, and Pike considered to be equally as important as the other two, but they said it should be an attitude assumed throughout the discourse and is not a phase of writing.[87]

Maxine Hairston, in a section on "Rogerian or nonthreatening argument" in her textbook A Contemporary Rhetoric, advised that one "shouldn't start writing with a detailed plan in mind" but might start by making four lists: the other's concerns, one's own key points, anticipated problems, and points of agreement or common ground.[89] She gave a different version of Young, Becker, and Pike's four phases, which she expanded to five and called "elements of the nonthreatening argument": a brief and objective statement of the issue; a neutrally worded analysis of the other's position; a neutrally worded analysis of one's own position; a statement of the common aspects, goals, and values that the positions share; and a proposal for resolving the issue that shows how both sides may gain.[90] She said that the Rogerian approach requires calm, patience, and effort, and will work if one is "more concerned about increasing understanding and communication" than "about scoring a triumph".[91] In a related article, she noted the similarity between Rogerian argument and John Stuart Mill's well-known phrase from On Liberty: "He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that."[92]

Robert Keith Miller's textbook The Informed Argument, first published in 1986,[93] presented five phases adapted from an earlier textbook by Richard Coe.[94] Miller's phases were: an introduction to the problem; a summary of views that oppose the writer's position; a statement of understanding of the region of validity of the opposing views; a statement of the writer's position; a statement of the situations in which the writer's position has merit; and a statement of the benefits of accepting the writer's position.[93]

In 1992, Rebecca Stephens built on the "vague and abstract" Rogerian principles of other rhetoricians to create a set of 23 "concrete and detailed" questions that she called a Rogerian-based heuristic for rhetorical invention,[95] intended to help people think in a Rogerian way while discovering ideas and arguments.[96] For example, the first two of her 23 questions are "What is the nature of the issue, in general terms?" (and she recommended that the answer should itself be stated as a question) and "Whose lives are affected by the issue?"[97] The last two questions are "What would have to happen to eliminate the disagreement among the opposing groups?" and "What are the chances that this will occur?"[98]

Ede's critique[]

Lisa Ede, a writing professor at Oregon State University, argued in a 1984 article—referring especially to some of the ideas of Young, Becker, and Pike—that "Rogerian rhetoric is not Rogerian" but is instead a distortion of Carl Rogers' ideas.[99] First, she criticized Young, Becker, and Pike for the inconsistency of suggesting that "Rogerian argument has no conventional structure" while at the same time they proposed four phases of writing that "look suspiciously like" a conventional adversarial structure.[100] She noted that Hairston's fifth phase of written Rogerian argument, a proposal for resolving the issue that shows how both sides may gain, "brings Rogerian rhetoric even closer to traditional argument".[101] Second, she judged that Young, Becker, and Pike underemphasized Rogers' unconditional acceptance of the other person and that they overemphasized advocacy of the writer's position, which is not part of Rogers' recommended practice.[102] Third, she found their description of the empathy required in Rogerian rhetoric to be no more than conventional audience analysis, which she considered to be much weaker than Rogers' more demanding description of empathy as standing in the other's shoes and seeing the world from the other's standpoint.[103] She said that Rogers' principles of congruence, unconditional acceptance of the other, and empathic understanding must be "deeply internalized or they become mere techniques", and she doubted whether the teaching of these principles in writing education had ever been successfully accomplished.[103]

Ede argued in 1987 that Young, Becker, and Pike's Rogerian rhetoric is weak compared to what she considered to be the "much more sophisticated" 20th-century rhetorics found in Kenneth Burke's A Grammar of Motives and Chaïm Perelman's The Realm of Rhetoric.[104] In her view, it is "not parsimonious" to coin the new term Rogerian rhetoric to refer to ideas that can already be found elsewhere in rhetorical theory.[104]

Young responded to Ede that he didn't know of any previous treatment in rhetorical theory of the kind of situation that Rogerian argument tries to address, where the techniques of the classical rhetorical tradition are likely to create or intensify extreme opposition, and where a deeper communication—of the kind that Rogers taught—is needed between and within people.[104] Young later admitted that the first presentation of Rogerian argument in his 1970 textbook[105] "may have been flawed",[106] but he thought that Rogerian argument could still be valuable "if it were modified in light of what we know now".[106] Young admitted, speaking for himself and his 1970 coauthors:

We did not pay enough attention to the considerable variation in actual dyadic situations; and we did not see that both the use and the usefulness of Rogerian argument seem to vary as the situation varies. The peculiarities of the particular situation affect, or should affect, the choices one makes in addressing it; not understanding this leads to inappropriate and ineffective choices.[107]

Limitations[]

Scholars debating Rogerian argument often noted limitations of the scope within which the Rogerian strategy is likely to be appropriate or effective.

In a 1968 paper that Anatol Rapoport wrote during, and in response to, the Vietnam War, he noted that the Rogerian approach was mostly irrelevant to the task of opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War.[109] Earlier, Rapoport had suggested that an "ethical debate between liberalism and communism, to be conducted according to the rules of role reversal, along lines proposed earlier by Carl Rogers" could help resolve conflict between the United States and communist states.[54] He had previously imagined that an earlier phase of the conflict was "largely a communication problem, one that could be attacked by 'men of good will' on both sides".[109] But he concluded that the Rogerian approach does not apply to situations such as the Vietnam War when it is "impossible to communicate" in a Rogerian way with "the beast, Status belligerens", a war-making state such as the Lyndon Johnson administration.[109] Rapoport noted: "Just as every proposition has a circumscribed region of validity, so does every method."[110] (Soon after, in opposition to Status belligerens, Rapoport relocated permanently to Canada from the United States,[111] leaving behind research connections with the military that he had since the 1940s.[112])

Young, Becker, and Pike pointed out in 1970 that Rogerian argument would be out of place in the typical mandated adversarial criminal procedures of the court system in the United States.[113]

Ede noted in 1984 that the rhetoric textbooks that discussed Rogerian argument dedicated only a few pages to it out of a total of hundreds of pages, so the Rogerian approach is only a small part of theories of rhetoric and argumentation.[114]

Feminist perspectives[]

In a 1990 article that combined ideas from feminist theorists and testimonies from women college students in the 1980s, women's studies professor Phyllis Lassner identified some limitations of Rogerian argument from women's perspectives.[116] One of Lassner's students "hated" Rogerian argument because "women have a right to be angry" and "everyone needs to know how they feel".[117] Lassner said that Rogers' psychology "is socially constructed on a foundation of cultural hegemony".[118] For women who are marginalized and have been taught that they are not "worthy opponents", Lassner said, "Rogerian rhetoric can be just as inhibiting and constraining as any other form of argumentation."[119] Some of Lassner's students doubted that their opponent (such as an anti-gay or anti-abortion advocate) could even recognize them or could conceal repugnance and rejection of them enough to make Rogerian empathy possible.[120] Lassner and her students especially disapproved of Hairston's advice to use neutrally worded statements, and they said that Hairston's ideal of neutrality was too "self-effacing" and "replicates a history of suppression" of women's voices and of their "authentic feeling".[121]

In a 1991 article, English professor Catherine Lamb agreed with Lassner and added: "Rogerian argument has always felt too much like giving in."[115] Lamb said that women (and men) need to have a theory of power and use it to evaluate alternative ways of communicating.[122] Lamb considered more recent negotiation theory such as Getting to Yes to be more complete than Rogers' earlier ideas about communication[123] (although there was Rogerian influence on Getting to Yes[124]), and she used negotiation theory in her writing classes.[125] In one of her class exercises, students worked in groups of three, role-playing three positions: two disputants in conflict and a third-party mediator.[126] The disputants wrote memos to the mediator, the mediator wrote a memo to a supervisor, and then all three worked together to write a mediation agreement, which was discussed with the teacher.[126] Subsequently a somewhat similar class exercise was included in later editions of Nancy Wood's textbook Perspectives on Argument, in a chapter on Rogerian argument.[127]

Young noted in 1992 that one potential problem with Rogerian argument is that people need it most when they may be least inclined to use it: when mutual antagonistic feelings between two people are most intense.[128] The way Rogerian argument had been taught in rhetoric textbooks may be effective for some situations, Young said, but is unlikely to work between two parties in the kind of situation when they need it most, when they are most intractably opposed.[128] Young suggested that third-party mediation, suggested by Rogers himself in 1951, may be most promising in that kind of situation.[128]

Related research on role reversal[]

Conflict researchers such as Morton Deutsch and David W. Johnson, citing the same publications by Rapoport and Rogers that inspired Rogerian rhetoric, used the term role reversal to refer to the presentation by one person to another person of the other person's position and vice versa.[129][130][131] Deutsch, Johnson, and others have done empirical research on this kind of role reversal (mostly in the late 1960s and 1970s), and the results suggested that the effectiveness of role reversal—in achieving desired outcomes such as better understanding of opponents' positions, change in opponents' positions, or negotiated agreement—depends on the issue and situation.[130][131][132]

Negotiation expert William Ury said in his 1999 book The Third Side that role reversal as a formal rule of argumentation has been used at least since the Middle Ages in the Western world: "Another rule dates back at least as far as the Middle Ages, when theologians at the University of Paris used it to facilitate mutual understanding: One can speak only after one has repeated what the other side has said to that person's satisfaction."[133] Ury listed such role reversal among a variety of other tools that are useful for conflict mediation, some of which may be more appropriate than role reversal in certain situations.[133] A kind of role reversal also featured among the advice in Getting to Yes,[134] the self-help book on negotiation written by Ury and Roger Fisher, along with that book's Rogerian-like emphasis on identifying common concerns between opposing parties in a conflict.[2][124]

See also[]

- Argumentation theory § Types of dialogue

- Bohm Dialogue

- Cognitive bias modification

- Conflict continuum

- Conflict transformation

- Dialectical thinking

- Dialogue

- Dialogue mapping

- Epistemic humility

- Epistemic virtue

- Group dynamics

- Immunity to change

- Interpersonal communication

- Intergroup dialogue

- Peace psychology

- Perspective-taking

- Philosophy of dialogue

- Reciprocal altruism

- Theories of rhetoric and composition pedagogy

- Thesis, antithesis, synthesis

Notes[]

- ^ Baumlin 1987, p. 36: "The Rogerian strategy, in which participants in a discussion collaborate to find areas of shared experience, thus allows speaker and audience to open up their worlds to each other, and in this attempt at mutual understanding, there is the possibility, at least, of persuasion. For in this state of sympathetic understanding, we recognize both the multiplicity of world-views and our freedom to choose among them—either to retain our old or take a new."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kroll 1997, p. 112: "For nearly three decades, Rogerian rhetoric has offered an important alternative to adversarial argument. More recently, certain strands of feminist rhetoric have created new interest in cooperative approaches. In 'Beyond Argument in Feminist Composition,' for example, Catherine Lamb draws attention to negotiation theory as an important source of alternatives to competitive and confrontational rhetoric. As Lamb explains: 'in both negotiation and mediation ... the goal has changed: it is no longer to win but to arrive at a solution in a just way that is acceptable to both sides' (18). And Michael Gilbert has developed a related approach that he calls 'coalescent argumentation,' an approach that involves a 'joining together' of divergent claims through 'recognition and exploration of opposing positions ... forming the basis for a mutual investigation of non-conflictual options' (837). ... This view is similar to the key idea in negotiation theory (especially the version presented in Roger Fisher and William Ury's Getting to Yes) that lying beneath people's 'positions' on issues are concerns and interests that represent what they care about most deeply. Positions are often intractable. But by shifting the conversation to underlying interests, it's often possible to find common concerns and shared values, on the basis of which there may be grounds for discussion and, ultimately, agreement."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kiefer 2005: "Based on Carl Rogers' work in psychology, Rogerian argument begins by assuming that a willing writer can find middle or common ground with a willing reader. Instead of promoting the adversarial relationship that traditional or classical argument typically sets up between reader and writer, Rogerian argument assumes that if reader and writer can both find common ground about a problem, they are more likely to find a solution to that problem. ... Rogerian argument is especially dependent on audience analysis because the writer must present the reader's perspective clearly, accurately, and fairly."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, Becker & Pike 1970, p. 282.

- ^ Erickson 2015, pp. 172–182.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ede 1984, p. 42: "I will focus on the original formulation of Rogerian rhetoric, that developed by Young, Becker, and Pike in Rhetoric: Discovery and Change, since it is both the clearest and certainly the most influential presentation of this approach. Young, Becker, and Pike were not the first to respond to this challenge. In fact, they rely heavily in their discussion of Rogerian rhetoric on the work of Anatol Rapoport, who in Fights, Games, and Debates, which they also quote in their text, attempts to apply Rogers' theories. It is Rapoport, for instance, who establishes the 'three methods of modifying images,' the Pavlovian, Freudian, and Rogerian, which appear early in Rhetoric: Discovery and Change as 'Rhetorical strategies and images of man.'"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Teich 1992, p. 65: "Rogerian principles were brought to the attention of writing teachers and rhetoricians in 1970 by Young, Becker, and Pike in Rhetoric: Discovery and Change. They came to Rogers through Anatol Rapoport's work in the area of conflict resolution. According to Rapoport (1960), Rogerian principles provided a means 'to convey to the opponent the assurance that he has been understood, so as to reduce his anxiety on that account and to induce him to listen' (289). From this, Young et al. developed a 'Rogerian strategy' of argument to apply especially 'in those dyadic situations that involve strong values and beliefs,' in which traditional argument 'tends to be ineffective.'"

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 7, 274, 282.

- ^ Kopelman 2020, pp. 63–64: "Rapoport joined the faculty of the University of Michigan ... in 1955, where he was one of the first three faculty members of the Mental Health Research Institute (MHRI) in the Department of Psychiatry. At the University of Michigan, Rapoport shifted the focus of his research to war and peace, conflict, and conflict resolution. He devoted himself to what he called the three arms of the peace movement: peace research, peace education, and peace activism. Rapoport made seminal contributions to game theory and published multiple books, including Fights, Games, and Debates (1960). ... Rapoport engaged not only in teaching and research, but also in peace activism ..."

- ^ Hairston 1976; Hairston 1982a; Hairston 1982b; Ede 1984, p. 47; Teich 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rapoport 1960a, pp. 273–288; Kecskemeti 1961, p. 1240; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 6–8; Ede 1984, p. 42.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 274; what Rapoport called the three outlooks in psychotherapy corresponded to categories of psychology that were well known enough that Rogers himself began a 1963 paper by referring to them, identifying himself as part of the third category: Rogers 1963, p. 72: "I share with Maslow and others the view that there are three broad emphases in American psychology. ... Associated with the first trend are terms such as behaviorism, objective, experimental, impersonal, logical-positivistic, operational, laboratory. Associated with the second current are terms such as Freudian, Neo-Freudian, psychoanalytic, psychology of the unconscious, instinctual, ego-psychology, id-psychology, dynamic psychology. Associated with the third are terms such as phenomenological, existential, self-theory, self-actualization, health-and-growth psychology, being and becoming, science of inner experience."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rapoport 1960a, p. 285.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 274.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rapoport 1960a, p. 278.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, pp. 275–277.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rapoport 1960a, pp. 279–285.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, pp. 280–284.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, pp. 284.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rapoport 1960a, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 286; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, p. 8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rogers 1951, p. 30; quoted in Ede 1984, p. 44; also cited (but not this quotation specifically) in Rapoport 1960a, pp. xiii, 286, 376.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rapoport 1960a, pp. 286–288; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 274–281.

- ^ Rogers 1952, which was cited or quoted in, for example: Rapoport 1960a; Rapoport 1969; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 284–289; Hairston 1976; Lunsford 1979; Bator 1980; Hairston 1982a, pp. 340–346; Ede 1984; Baumlin 1987.

- ^ Rogers 1951.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rogers 1952, p. 83.

- ^ Rogers 1952, p. 83; the word conviction is Rapoport's: Rapoport 1961, p. 215.

- ^ Rogers 1952, p. 84.

- ^ Rogers 1952, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Rogers 1952, p. 86.

- ^ Third-party intervention is not mentioned (except in reprints of Rogers' 1951 paper) in the discussion of Rogerian argument in the textbooks: Young, Becker & Pike 1970; Hairston 1982a; Flower 1985; Coe 1990; Memering & Palmer 2006; Lunsford & Ruszkiewicz 2012; Barnet, Bedau & O'Hara 2020.

- ^ Rogers 1952, pp. 86–88: "A third party, who is able to lay aside his own feelings and evaluations, can assist greatly by listening with understanding to each person or group and clarifying the views and attitudes each holds. We have found this very effective in small groups in which contradictory or antagonistic attitudes exist. ... This procedure has important characteristics. It can be initiated by one party, without waiting for the other to be ready. It can even be initiated by a neutral third person, providing he can gain a minimum of cooperation from one of the parties." On the "third side" in conflict, see also Ury 2000.

- ^ Rosenberg 2003, p. xvii.

- ^ Kay Halasek, "The fully functioning person, the fully functioning writer: Carl Rogers and expressive pedagogy", in Teich 1992, pp. 141–158.

- ^ One summary of the debates is: Richard M. Coe, "Classical and Rogerian persuasion: an archeological/ecological explication", in Teich 1992, pp. 93–108.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, p. 7.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 5, 8.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 273–274; later, Teich 1992, p. 66 concluded: "Rogers' principles have been treated most persuasively when applied to argumentation in dyadic rather than triadic situations."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lunsford 1979, p. 148.

- ^ Lunsford 1979, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Lunsford 1979, pp. 149.

- ^ Lunsford 1979, pp. 150.

- ^ James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, "Rogerian and Platonic dialogue in—and beyond—the writing classroom", in Teich 1992, pp. 123–140.

- ^ Bator 1980.

- ^ Bator 1980, p. 428.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bator 1980, p. 429.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Brent 1996.

- ^ White 1969, p. 29: "... please recall again the Hovland experiments, and also the rather large number of other experiments that bring out, in one way or another, the desirability of discovering common ground if conflict is to be resolved. For instance, there are the experiments of Blake and Mouton on how each side in a controversy ordinarily underestimates the amount of common ground that actually exists between its own position and that of its adversary. There is all the research on the non-zero-sum game, and the need to keep the players on both sides from treating a non-zero-sum game, in which the adversaries actually share some common interests, as if it were a zero-sum game in which loss for one side always means gain for the other. There is the so-called Rapoport Debate (actually originated by Carl Rogers, apparently), in which neither side is permitted to argue for its position until it has stated, to the other side's satisfaction, what the other side is trying to establish."

- ^ Nettler 2003, p. 30: "Whether particular individuals are deemed to be 'reason-able,' and how often under what circumstances, will depend on tests of ability 'to listen to reason.' And more than that, to appreciate others' reasons. One conceivable test of this ability, and yet a difficult test, applies 'the Rapoport debate' (after its inventor, Anatol Rapoport, 1974). This procedure requires disputants to repeat accurately their opponents' arguments before they present their own counter-arguments. It takes the heat out of quarrel, and works toward mutual comprehension—if that is sought—by forcing me to restate your thesis satisfactorily before I rebut it, and vice versa."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rapoport 1960a, pp. 289, 309: "The reciprocal task has been proposed as the foundation of ethical debate, namely, the task of stating the opponent's case as clearly and eloquently as possible ... I have tried to apply the principle of ethical debate outlined in the preceding chapters ..." / Rapoport 1969, p. 21: "On several occasions I outlined the so-called ethical debate between liberalism and communism, to be conducted according to the rules of role reversal, along lines proposed earlier by Carl Rogers. The aim of ethical debate is to bring out the common ground of the two positions, to increase the effectiveness of communication between the opponents, and to induce a perception of similarity."

- ^ Dennett 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Austin 2019, p. 114.

- ^ Boghossian & Lindsay 2019, p. 97.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rapoport 1960b, p. 411: "In addition to these proposals by Hayakawa and by Rogers, namely, to try to induce listening by example and by making listening advantageous, I submit two further principles of rational debate. One of them I call the delineation of the area of validity of the opponent's position; the other, the assumption of similarity. To delineate the validity of a position means to state the conditions under which the position is justified. Practically every opinion, even seemingly absurd ones, can be partly justified. If someone maintains that black is white, we can always say, 'Yes, that is true, if you are interpreting a photographic negative.' ... The assumption of similarity is more difficult to define. It is not enough to say that you must ascribe to the opponent a psyche similar to your own. You must do so all the way, not just part of the way."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rapoport 1961, pp. 215–218: "A human opponent in real life (as opposed to parlor games) is rarely all enemy. Usually, he is part friend, part foe. Mutual recognition of the common area of interest is a problem of communication, not of strategy. And so is the problem of modifying the outlook of the other. ... Hayakawa has proposed that we listen to the Russians in order to get them to listen: if we listen long enough and earnestly enough, they may begin to imitate us. It has also been proposed by Carl Rogers that in a rational debate each opponent, before he is allowed to state his own case, should be required to state the case of the other to the other's satisfaction, in order to convince the other that he has been understood. ... If the present conflict between the Communist and the non-Communist worlds is to be lifted above the level of a fight and above the level of a game of maneuver, to the level of debate where the issues can be squarely faced, we must first learn to listen; second we need to find out and to admit the extent to which the opponent's position has merit; third we need to probe deeply within ourselves to discover the profound similarities between us and them. ... a shift in the other's outlook can occur only if he has re-examined it, and he will re-examine it only if he listens to some one else, and he will listen only if he is listened to. But if we really are ready to listen, then we are ready to re-examine our own outlook. The courage needed to become genuinely engaged in a genuine debate is the courage to be prepared to accept a change in one's own outlook.

- ^ Hart 1963, p. 108.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 286.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rapoport 1960a, p. 287.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 276.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, pp. 301–302; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 301.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 300.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rapoport 1960a, p. 306.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 309.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 288, 306; Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Rapoport 1961, p. 218.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dennett 2013, p. 33.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Dennett 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Boghossian & Lindsay 2019, p. 98.

- ^ Austin 2019, pp. 109–114.

- ^ Austin 2019, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Austin 2019, p. 111.

- ^ Erickson 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Erickson 2015, p. 180.

- ^ Austin 2019, pp. 111–112; "The inadequacy of individual rationality" in Rapoport 1960a, pp. 174–177; "The assumption of similarity" in Rapoport 1960a, pp. 306–309.

- ^ Rapoport 1961, p. 210; see also Rapoport 1960a, p. 9.

- ^ Rapoport 1961, pp. 212–214; see also Rapoport 1960a, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Rapoport 1961, p. 215; see also Rapoport 1960a, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Rapoport 1961, pp. 214–215; see also Rapoport 1960a, pp. 227–242 and Erickson 2015, pp. 189–198.

- ^ Rapoport 1960a, p. 308; see also Erickson, pp. 189–198.

- ^ Austin 2019, pp. 111–114.

- ^ Teich 1992, p. 23: "He conceded that problems of transferring his principles from oral to written communication had 'never been a primary interest' of his."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Young, Becker & Pike 1970, p. 283.

- ^ Kiefer 2005.

- ^ Hairston 1982a, p. 344.

- ^ Hairston 1982a, p. 345.

- ^ Hairston 1982a, p. 346.

- ^ Hairston 1976, p. 375.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miller 1998.

- ^ Coe 1990.

- ^ Teich 1992, pp. 162.

- ^ Teich 1992, pp. 159–166.

- ^ Teich 1992, p. 163.

- ^ Teich 1992, p. 164.

- ^ Ede 1984, p. 40; Teich 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Ede 1984, p. 43.

- ^ Ede 1984, p. 47.

- ^ Ede 1984, p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ede 1984, p. 46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Teich 1992, p. 81.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Teich 1992, p. 110.

- ^ Teich 1992, p. 111.

- ^ Rapoport 1969, pp. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rapoport 1969, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Rapoport 1969, p. 21.

- ^ Kopelman 2020, p. 65; Erickson 2015, p. 202.

- ^ Erickson 2015, p. 177.

- ^ Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 273–274: "For example, it would be highly unusual, to say the least, if a defense attorney ... acknowledged in court that his client was guilty." This idea was repeated by Richard M. Coe in Teich 1992, p. 86.

- ^ Ede 1984, p. 41.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lamb 1991, p. 17; Paul G. Bator reported a student's similar complaint in Teich 1992, p. 230: "The writer can appear 'wimpy'—especially in issues that require a firm stance".

- ^ Lassner 1990.

- ^ Lassner 1990, p. 221.

- ^ Lassner 1990, p. 222.

- ^ Lassner 1990, p. 223.

- ^ Lassner 1990, p. 225.

- ^ Lassner 1990, pp. 227–229.

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 17–21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b A source that mentions the Rogerian influence on Getting to Yes is Wheeler & Waters 2006: "The authors also drew lessons on process from Chris Argyris, John Dunlop, Jim Healy, and Carl Rogers."

- ^ Lamb 1991, p. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lamb 1991, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Wood 2004, pp. 269–271.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Richard E. Young, "Rogerian argument and the context of situation: taking a closer look", in Teich 1992, pp. 109–121.

- ^ Johnson 1967, p. 135: "Cohen (1950, 1951) proposed that negotiators role-reverse with each other to gain a clearer understanding of the opponent's and one's own positions. Rogers (1952) stated that the use of role reversal will result in an understanding of the opponent's frame of reference and a reduction of threat and defensiveness in the situation. Rapoport (1960, 1962) suggested that role reversal be used to remove the threat of looking at other points of view and to convince the opponent that he has been clearly heard and understood. Finally, Deutsch (1962) stated that role reversal, by forcing one to place the other's action in a context which is acceptable to the other, creates conditions in which the current validity of the negotiators' assumptions can be examined, and reduces the need for defensive adherence to a challenged viewpoint or behavior."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Muney & Deutsch 1968, p. 345: "The importance of the ability to take the role of the other for human communication and cooperation has also been stressed by theorists who have been concerned with ways of facilitating the resolution of intrapsychic, interpersonal, or international conflict. These theorists (Moreno, 1955; Cohen, 1950, 1951; Rogers, 1952; Rapoport, 1960; Deutsch, 1962) have advocated role-reversal as a means of reducing conflict. "Role-reversal" is a discussion procedure in which individual A presents individual B's viewpoint while individual B reciprocates by presenting A's viewpoint. They have postulated that such mutual taking of one another's role alleviates conflict by such processes as: reducing self-defensiveness, increasing one's understanding of the other's views, increasing the perceived similarity between self and other, increasing the awareness of the positive features in the other's viewpoint and the dubious elements in one's own position."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson 1971, p. 321: "Role reversal, therefore, can be defined as a procedure in which one or both of two persons in a discussion presents the viewpoint and feelings of the other in an accurate, warm, and authentic way. The several theorists who have discussed role reversal (Cohen, 1950, 1951; Rogers, 1952, 1965; Rapoport, 1960, 1962; Deutsch, 1962b) have hypothesized that role reversal will have effects upon both the sender and the receiver in a communication situation. The author's refinements and extensions of these hypotheses will be presented in the following sections of this article. Here it is sufficient to state that despite the speculation concerning role reversal as a procedure to increase the effectiveness of communication in conflict situations, and despite the promising results found by various practitioners who have used it, there has been no systematic research on its use until recently."

- ^ Weiss-Wik 1983, pp. 729–730: "Bilateral focus, also called 'role reversal,' 'active listening,' and 'restatement,' originated in Carl Rogers's psychotherapeutic approach and was first adopted in our literature by Rapoport (1960). To be distinguished from 'self-presentation,' bilateral focus involves restating a counterpart's views to his or her satisfaction. It may flush out the assumptions that Nierenberg and others fault for misunderstanding. It is intended to improve understanding, to increase trust, and (potentially) to promote the compatibility of negotiators' goals. ... But the results above argue against its use or, less emphatically, for cautious use of the procedure by a negotiator. It may be particularly effective for what Boulding (1978) has called 'illusory conflict'; then again, in that case it would eliminate the necessity for negotiation. Its efficacy may depend on the nature of the issue at hand and on the opponent's attitude toward its use."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ury 2000, p. 148.

- ^ Zariski 2010, p. 213: "Another theory of idea generation may be described as 'cognitive role reversal,' in which a party may, by thinking about the conflict from the perspective of the other party, become aware of ideas that the other party may find attractive as part of a solution (Fisher and Ury 1981). Some describe this approach as aiming at 'cognitive empathy' or 'transactional empathy' between the parties (Della Noce 1999)."

References[]

- Austin, Michael (2019). "Rapoport's rules". We must not be enemies: restoring America's civic tradition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 109–114. ISBN 9781538121252. OCLC 1064581867.

- Bator, Paul (December 1980). "Aristotelian and Rogerian rhetoric". College Composition and Communication. 31 (4): 427–432. doi:10.2307/356593. JSTOR 356593.

- Baumlin, James S. (Winter 1987). "Persuasion, Rogerian rhetoric, and imaginative play". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 17 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1080/02773948709390765. JSTOR 3885207.

- Boghossian, Peter G.; Lindsay, James A. (2019). "Five advanced skills for contentious conversations: how to rethink your conversational habits". How to have impossible conversations: a very practical guide. New York: Lifelong Books, Da Capo Press. pp. 95–130. ISBN 9780738285320. OCLC 1085584392.

- Brent, Douglas (1996). "Rogerian rhetoric: ethical growth through alternative forms of argumentation". In Emmel, Barbara; Resch, Paula; Tenney, Deborah (eds.). Argument revisited, argument redefined: negotiating meaning in the composition classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. pp. 73–96. ISBN 978-0761901846. OCLC 34114559. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- Dennett, Daniel C. (2013). "A dozen general thinking tools: 3. Rapoport's rules". Intuition pumps and other tools for thinking. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9780393082067. OCLC 813539169.

- Ede, Lisa (September 1984). "Is Rogerian rhetoric really Rogerian?". Rhetoric Review. 3 (1): 40–48. doi:10.1080/07350198409359078. JSTOR 465729.

- Erickson, Paul (2015). The world the game theorists made. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226097206.001.0001. ISBN 9780226097039. OCLC 905759302.

- Hairston, Maxine (December 1976). "Carl Rogers's alternative to traditional rhetoric". College Composition and Communication. 27 (4): 373–377. doi:10.2307/356300. JSTOR 356300.

- Hairston, Maxine (September 1982b). "Using Carl Rogers' communication theories in the composition classroom". Rhetoric Review. 1 (1): 50–55. doi:10.1080/07350198209359035. JSTOR 465557.

- Hart, Alice Gorton (May 1963). "Book review: New insights on conflicts: Fights, games and debates by Anatol Rapoport". ETC.: A Review of General Semantics. 20 (1): 106–109. JSTOR 42574000.

- Johnson, David W. (October 1967). "Use of role reversal in intergroup competition". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 7 (2, Pt.1): 135–141. doi:10.1037/h0025001.

- Johnson, David W. (1971). "Role reversal: a summary and review of the research". International Journal of Group Tensions. 1 (4): 318–334. ISSN 0047-0732.

- Kecskemeti, Paul (April 1961). "Book review: Fights, games, and debates by Anatol Rapoport". Science. 133 (3460): 1240. doi:10.1126/science.133.3460.1240. JSTOR 1707252.

- Kiefer, Kate (2005). "What is Rogerian argument?". writing.colostate.edu. Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- Kopelman, Shirli (February 2020). "Tit for tat and beyond: the legendary work of Anatol Rapoport". Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. 13 (1): 60–84. doi:10.1111/ncmr.12172.

- Kroll, Barry M. (Autumn 1997). "Arguing about public issues: what can we learn from practical ethics?". Rhetoric Review. 16 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1080/07350199709389083. JSTOR 465966.

- Lamb, Catherine E. (February 1991). "Beyond argument in feminist composition". College Composition and Communication. 42 (1): 11–24. doi:10.2307/357535. JSTOR 357535.

- Lassner, Phyllis (Spring 1990). "Feminist responses to Rogerian argument". Rhetoric Review. 8 (2): 220–232. doi:10.1080/07350199009388895. JSTOR 465594.

- Lunsford, Andrea A. (May 1979). "Aristotelian vs. Rogerian argument: a reassessment". College Composition and Communication. 30 (2): 146–151. doi:10.2307/356318. JSTOR 356318.

- Muney, Barbara F.; Deutsch, Morton (1968). "The effects of role-reversal during the discussion of opposing viewpoints". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 12 (3): 345–356. doi:10.1177/002200276801200305. JSTOR 172670.

- Nettler, Gwynn (2003). Boundaries of competence: how social studies make feeble science. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 30. doi:10.4324/9781315082059. ISBN 0765801795. OCLC 52127637.

- Rapoport, Anatol (1960a). Fights, games, and debates. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. OCLC 255500.

- Rapoport, Anatol (Summer 1960b). "On communication with the Soviet Union, part II". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 17 (4): 401–414. JSTOR 42573860. The first page of this article notes that its argument is based on Rapoport 1960a.

- Rapoport, Anatol (April 1961). "Three modes of conflict". Management Science. 7 (3): 210–218. doi:10.1287/mnsc.7.3.210. JSTOR 2627528.

- Rapoport, Anatol (March 1969) [1968]. "The question of relevance". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 26 (1): 17–33. JSTOR 42576317. This paper was written for the International Conference on General Semantics held from 5–9 August 1968.

- Rogers, Carl R. (1951). Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications, and theory. The Houghton Mifflin psychological series. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2571303.

- Rogers, Carl R. (Winter 1952) [1951]. "Communication: its blocking and its facilitation". ETC.: A Review of General Semantics. 9 (2): 83–88. JSTOR 42581028. This paper was written for Northwestern University's Centennial Conference on Communications held on 11 October 1951. It was later reprinted as a book chapter with a different title: Rogers, Carl R. (1961). "Dealing with breakdowns in communication—interpersonal and intergroup". On becoming a person: a therapist's view of psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 329–337. OCLC 172718. It was also reprinted in full in the book that popularized Rogerian rhetoric, Young, Becker & Pike 1970, pp. 284–289.

- Rogers, Carl R. (April 1963). "Toward a science of the person". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 3 (2): 72–92. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.994.8868. doi:10.1177/002216786300300208.

- Rosenberg, Marshall B. (2003) [1999]. Nonviolent communication: a language of life. Non-violent communication guides (2nd ed.). Encinitas, CA: PuddleDancer Press. ISBN 9781892005038. OCLC 52312674.

- Teich, Nathaniel, ed. (1992). Rogerian perspectives: collaborative rhetoric for oral and written communication. Writing research. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing. ISBN 978-0893916671. OCLC 24504867.

- Ury, William (2000) [1999]. The third side: why we fight and how we can stop. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140296344. OCLC 45610553. Originally published with the title Getting to peace: transforming conflict at home, at work, and in the world.

- Weiss-Wik, Stephen (December 1983). "Enhancing negotiators' successfulness: self-help books and related empirical research". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 27 (4): 706–739. doi:10.1177/0022002783027004008. JSTOR 173893.

- Wheeler, Michael A.; Waters, Nancy J. (October 2006). "The origins of a classic: Getting to yes turns twenty‐five". Negotiation Journal. 22 (4): 475–481. doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.2006.00117.x.

- White, Ralph K. (Autumn 1969). "Three not-so-obvious contributions of psychology to peace". Journal of Social Issues. 25 (4): 23–39. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1969.tb00618.x.

- Zariski, Archie (April 2010). "A theory matrix for mediators". Negotiation Journal. 26 (2): 203–235. doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.2010.00269.x.

Textbooks[]

Some rhetoric and composition textbooks that have a section about Rogerian argument, listed by date of first edition:

- Young, Richard Emerson; Becker, Alton L.; Pike, Kenneth L. (1970). Rhetoric: discovery and change. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 1–10, 273–290. ISBN 978-0155768956. OCLC 76890.

- Hairston, Maxine (1982a) [1974]. A contemporary rhetoric (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 340–346, 362. ISBN 0395314941. OCLC 8783574. A later edition was published as: Hairston, Maxine (1986). Contemporary composition (4th, short ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 345–351, 364–365. ISBN 0395402824. OCLC 13859540.

- Coe, Richard M. (1990) [1981]. "Rogerian persuasion". Process, form, and substance: a rhetoric for advanced writers (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 395–411. ISBN 0133266044. OCLC 20672101.

- Flower, Linda (1985) [1981]. "Rogerian argument". Problem-solving strategies for writing (2nd ed.). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 179–181. ISBN 0155719769. OCLC 11749018. Several later editions of this textbook were published.

- Miller, Robert Keith (1998) [1986]. "Rogerian argument". The informed argument: a multidisciplinary reader and guide (5th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. pp. 19–21. ISBN 0155038095. OCLC 37575984. Several later editions of this textbook were published.

- Wood, Nancy V. (2004) [1995]. "Rogerian argument and common ground". Perspectives on argument (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 245–271. ISBN 0131823744. OCLC 51898807. Several later editions of this textbook were published.

- Lunsford, Andrea A.; Ruszkiewicz, John J. (2012) [1999]. "Rogerian and invitational arguments". Everything's an argument (6th ed.). New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 127–131. ISBN 9781457606069. OCLC 816655992. Several later editions of this textbook were published.

- Memering, Dean; Palmer, William (2006) [2002]. "Rogerian argument". Discovering arguments: an introduction to critical thinking and writing, with readings (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 103–105. ISBN 0131895672. OCLC 61879680. Several later editions of this textbook were published.

- Barnet, Sylvan; Bedau, Hugo Adam; O'Hara, John (2020) [2005]. "A psychologist's view: Rogerian argument". From critical thinking to argument: a portable guide (6th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 397–412. ISBN 9781319194437. OCLC 1140193069.

Further reading[]

- Bean, John C. (October 1986). "Summary writing, Rogerian listening, and dialectic thinking". College Composition and Communication. 37 (3): 343–346. doi:10.2307/358053. JSTOR 358053.

- Correia, Vasco (2012). "The ethics of argumentation". Informal Logic. 32 (2): 222–241. doi:10.22329/il.v32i2.3530.

- Davis II, James T. (July 2012). "What is the future of 'non-Rogerian' analogical Rogerian argument models?". Rhetoric Review. 31 (3): 327–332. doi:10.1080/07350198.2012.684007.

- Dziamka, Kaz (16 May 2007). "Just shut up and listen to your enemy: whatever happened to Rogerian argument?". counterpunch.org. CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- Gilbert, Michael A. (1997). Coalescent argumentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0805825190. OCLC 35145878.

- Knoblauch, A. Abby (December 2011). "A textbook argument: definitions of argument in leading composition textbooks" (PDF). College Composition and Communication. 63 (2): 244–268. JSTOR 23131584. An analysis of how Rogerian argument is portrayed in writing textbooks.

- Kroll, Barry M. (Spring 2000). "Broadening the repertoire: alternatives to the argumentative edge". Composition Studies. 28 (1): 11–27. JSTOR 43501445.

- Kroll, Barry M. (2013). The open hand: arguing as an art of peace. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgnz9. ISBN 9780874219265. JSTOR j.ctt4cgnz9. OCLC 852222392.

- Mnookin, Robert H.; Peppet, Scott R.; Tulumello, Andrew S. (July 1996). "The tension between empathy and assertiveness". Negotiation Journal. 12 (3): 217–230. doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.1996.tb00096.x.

- Rogers, Carl R.; Roethlisberger, Fritz Jules (July 1952). "Barriers and gateways to communication". Harvard Business Review. 30 (4): 46–52.

- Stone, Douglas; Patton, Bruce; Heen, Sheila (1999). Difficult conversations: how to discuss what matters most. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670883395. OCLC 40200290. The authors, from the Harvard Negotiation Project, wrote: "Our work on listening and the power of authenticity was influenced by Carl Rogers ..." (p. x)

- Wilbers, Stephen. "Rogerian argument & persuasion". wilbers.com. Retrieved 2017-06-09. Compendium of columns on Rogerian rhetoric, some of which were published in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

- Dispute resolution

- Philosophical arguments

- Rhetoric