Ruhrpolen

Ruhrpolen (German: [ˈʁuːɐ̯ˌpoːlən], “Ruhr Poles”) is a German umbrella term for the Polish migrants and their descendants who lived in the Ruhr area in western Germany since the 19th century. The Poles (including Masurians,[1][2][3] Kashubians,[4] Silesians, and other groups) migrated to the rapidly industrializing region from Polish-speaking areas of the German Empire.

Origins[]

The immigrants mainly came from what was then eastern provinces of Germany (Province of Posen, East Prussia, West Prussia, Province of Silesia), which were acquired by the Kingdom of Prussia in the late-18th-century Partitions of Poland or earlier, and which housed a significant Polish-speaking population. This migration wave, known as the Ostflucht, began in the late 19th century, with most of the Ruhrpolen arriving around the 1870s. The migrants found employment in the mining, steel and construction industries. In 1913 there were between 300,000 and 350,000 Poles and 150,000 Masurians. Of those, one-third were born in the Ruhr area.[5] The Protestant Masurians did not accept being identified with Catholic Poles and underlined their loyalty to Prussia and the German Empire.[6]

German Empire[]

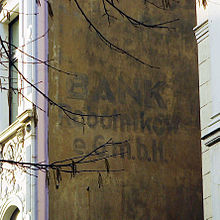

The first Polish organization Jedność was founded in 1876 in Dortmund by bookseller Hipolit Sibilski.[7] In 1890, Wiarus Polski, the first Polish newspaper in the region, was established in Bochum.[7] Various Polish organizations were founded in the region, including Towarzystwo św. Michała ("St. Michael's Club") in 1888,[8] Związek Polaków w Niemczech ("League of Poles in Germany") in 1894, a regional branch of the "Sokół" Polish Gymnastic Society in 1898,[9] and ("Polish Professional Union") in 1902.[10] Dozens of Polish bookstores were founded in various places, including Dortmund, Bochum, Herne, Witten, Recklinghausen, Oberhausen, (present-day district of Castrop-Rauxel), (present-day district of Gelsenkirchen), and Laar (present-day districts of Duisburg).[11] There were also various Polish companies, co-operative shops, banks,[12] sports clubs and singing clubs.[13] In 1904, the Dziennik Polski daily newspaper was founded in Dortmund, and in 1909 the Narodowiec newspaper was founded in Herne.[14] The two most successful and popular football clubs of the Ruhr region, FC Schalke 04 and Borussia Dortmund, were co-founded by Poles,[15] and the former was even mockingly called the Polackenverein ("Polack club") by the Germans because of its many players of Polish origin.[16]

The main center of the Polish community of the Ruhr area was Bochum, and since 1905, many organizations and enterprises were based at Am Kortländer Street,[12] which was hence nicknamed "Little Warsaw".[13] The former Redemptorist Monastery in Bochum, which was closed down by the Prussian government during the Kulturkampf in 1873, was reopened and became a Polish religious center.[17]

The rights of the Ruhrpolen as citizens were restricted in many ways by anti-Polish policies of the German Empire.[18] While initially German officials hoped that the Polish population would succumb to Germanization, they eventually lost hope that the long-term strategy would succeed.[19] Polish schools had their accreditation refused, and state schools no longer took account of ethnic diversity.[20] In schools with a high percentage of Polish-speaking students, German officials split up the students.[20] When parents tried to organise private lessons for their children, police would come to their homes.[20] Germany banned the use of the Polish language in schools (since 1873), in mines (since 1899), and at public gatherings (since 1908).[12] Polish publishing houses and bookstores were often searched by the German police, and Polish patriotic books and publications were confiscated.[21] Polish booksellers whose books were confiscated were sentenced by German courts to fines or prison.[22] In 1909, the Central Office for Monitoring the Polish Movement in the Rhine-Westphalian Industrial Districts (Zentralstelle fur Uberwachung der Polenbewegung im Rheinisch-Westfalischen Industriebezirke) was established by the Germans in Bochum.[23]

Other measures included instructing teachers and officials that their duty was to promote a German national consciousness. A decree was issued that ordered all miners to speak German. Discrimination started to affect issues of basic existence.[20] The made it difficult for Poles who wished to return east to purchase land. In 1908, laws discriminating against the Polish language were applied to the entire German Empire.[20]

In response to harassment by Prussian authorities, the organisations of Ruhr Poles expanded what had been their purely cultural character and restored their links with Polish organisations in the east. The League of Poles in Germany, founded at Bochum in 1894, merged with the ''Straż'' Movement set up in 1905. In 1913, the combined group formed an executive committee, which worked alongside the Polish National Council.[24] Poles also demanded Polish priests and mass services in Polish.[25]

Interbellum and World War II[]

After the end of World War I and the rebirth of independent Poland, many Poles left the region and returned to Poland, although a sizeable community stayed. In the interbellum, the main Polish newspaper of the Ruhr Poles was Naród, issued in Herne since 1921.[26] Bochum was the headquarters of the Third District of the Union of Poles in Germany, which covered not only Westphalia and Rhineland, within which the Ruhr is located, but also Baden and the Palatinate.[27] According to 1935 estimates, Polish organizations in Westphalia and Rhineland had 21,500 members.[26]

In early 1939, there were no anti-Polish riots in the Ruhr area, although Nazi Germany increased both its invigilation of Polish activists and organizations, and the censorship of Polish press.[26] Polish activists, expecting a German attack, secured the files of Polish organizations.[26] On 15 July 1939, the Gestapo entered the headquarters of the Union of Poles in Germany in Bochum, searched it and interrogated its chief Michał Wesołowski.[28] The Nazis then carried out mass searches of Polish organizations in the region and interrogated Polish activists, however, they did not obtain the desired lists of Polish activists, which had been previously hidden by Poles.[29] Nazi terror and persecutions rapidly intensified. The Nazis limited freedom of assembly, increased censorship and confiscated Polish press for reporting on the persecution and arrests of Poles.[29] In response, many Poles from the region came to Bochum for organizational and information meetings.[29] On 24 August 1939, the Gestapo, under threat of arrest, demanded 30 leading Polish activists to appear at the Gestapo station in Bochum and present lists of members of Polish organizations, but again to no avail.[29] Due to increasing German repressions, many Polish organizations suspended public activity.[30]

After the outbreak of the Second World War, all remaining Polish organizations in the Ruhr faced dissolution by the Nazis. On 11 September 1939, 249 leading Polish activists from the Ruhr were arrested and then placed in concentration camps.[30] At least 60 of them were murdered for their activities by Nazi Germany.[31][32] Headquarters of Polish organizations and premises in Bochum were looted and expropriated by Nazi Germany.[12] The Gestapo closed the Polish monastery in Bochum, which was then converted into a transit camp for people deported from German-occupied Lithuania.[17] It was destroyed during air raids in 1943, rebuilt afterwards,[17] and eventually demolished in 2012.[33] Shortly before demolition, the church bells were sent to Poland.[33]

Aftermath[]

It is estimated that in modern times, some 150,000 inhabitants of the Ruhr Area (out of roughly five million) are of Polish descent.

Notable people[]

This list is incomplete; you can help by . (June 2016) |

- Rüdiger Abramczik, footballer and coach

- Herbert Burdenski, footballer and coach

- Leon Goretzka, footballer

- Ernst Kalwitzki, footballer

- Erich Kempka, Adolf Hitler's chauffeur.[35]

- Stanislaus Kobierski, footballer[36]

- Willi Koslowski, footballer

- Ernst Kuzorra, footballer

- Heinz Kwiatkowski, footballer

- Reinhard Libuda, footballer

- Stanisław Mikołajczyk, politician, Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile during World War II

- Hans Nowak, footballer

- Emil Rothardt, footballer

- Günter Sawitzki, footballer

- Fritz Szepan, footballer[16]

- Horst Szymaniak, footballer

- Hans Tibulski, footballer

- Otto Tibulski, footballer

- Adolf Urban, footballer[16]

References[]

- ^ http://www.oberschlesisches-landesmuseum.de/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=193:tagung-qspuren-der-oberschlesier-und-polen-in-nordrhein-westfalenq&catid=76:aktuelles

- ^ http://www.migrationsroute.nrw.de/erinnerungsort.php?erinnerungsort=Bochum

- ^ "Timelines Germany: Ruhrpolen".

- ^ "Nationales Denken im Katholizismus der Weimarer Republik", Reinhard Richter, Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2000, page 319

- ^ The German melting-pot: multiculturality in historical perspective, Wolfgang Zank, page 139, Palgrave Macmillan 1998

- ^ Stefan Goch, Polen nicht deutscher Fußballmeister. Die Geschichte des FC Gelsenkirchen-Schalke 04, in: Der Ball ist bunt. Fußball, Migration und die Vielfalt der Identitäten in Deutschland: Hrsg: Diethelm Blecking/Gerd Dembowski. Frankfurt a.M. 2010, p.237-249.

- ^ a b Chojnacki, Wojciech (1981). "Księgarstwo polskie w Westfalii i Nadarenii do 1914 roku". Studia Polonijne (in Polish). No. 4. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. p. 201.

- ^ Jacek Barski. "St Michael's Polish Club in Recklinghausen, 1913". Porta Polonica. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Krzysztof Ruchniewicz. "The Polish gymnastics club "Sokół"". Porta Polonica. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 204

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 201, 204-205

- ^ a b c d "Bochum as the center of the Polish movement". Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ a b ""Klein Warschau" an der Ruhr" (in German). Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 203

- ^ "Polacy". Borussia.com.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Nazizm, wojna i klub Polaczków – historia Adolfa Urbana". Historia.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Polnische Seelsorger im Ruhrgebiet" (in German). Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Migration Past, Migration Future:Germany and the United States Myron Weiner, page 11, Berghahn Books 1997

- ^ Imperial Germany, 1871-1918: economy, society, culture, and politics, Volker Rolf Berghahn, pages 107-108,Berghahn Books 2004

- ^ a b c d e Imperial Germany... pages 107-108

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 202-203

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 206

- ^ Chojnacki, p. 202

- ^ Imperial Germany... page 218

- ^ Imperial Germany... page 108

- ^ a b c d Cygański, Mirosław (1984). "Hitlerowskie prześladowania przywódców i aktywu Związków Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1939-1945". Przegląd Zachodni (in Polish) (4): 55.

- ^ Cygański, p. 54

- ^ Cygański, p. 55-56

- ^ a b c d Cygański, p. 56

- ^ a b Cygański, p. 57

- ^ Weimar and Nazi Germany:Panikos Panayi, Longman 2000, page 235

- ^ Cygański, p. 58

- ^ a b Sabine Vogt (25 July 2012). "Der Kirchturm fällt nächste Woche". Der Westen (in German). Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "DORTMUND: St. Anna". Polska Misja Katolicka w Dortmundzie (in Polish). Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Kempka, Erich (2010) [1951]. I was Hitler's Chauffeur. London: Frontline Books-Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-84832-550-0. p. 10

- ^ Stefan Szczepłek. "Z Niemcami warto grać". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- German people of Polish descent

- Industrial history of Germany

- Prussian Partition

- Polish minority in Germany

- Germany–Poland relations

- 19th century in Germany

- 20th century in Germany

- Slavic ethnic groups

- History of North Rhine-Westphalia