Rupi Kaur

Rupi Kaur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 October 1992 Punjab, India |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | University of Waterloo (BA, 2015)[1] |

| Occupation | Author, poet, artist, illustrator, performer |

| Website | www.rupikaur.com |

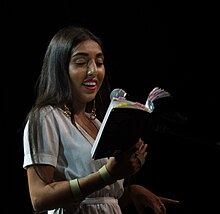

Rupi Kaur (born 5 October 1992) is an Indian-born Canadian poet, illustrator, photographer, and author. Born in Punjab, India, Kaur immigrated to Canada at a young age with her family. She began performing poetry in 2009 and rose to prominence on Instagram, eventually becoming one of the most popular "Instapoets" through her three collections of poetry.

In March 2015, as a part of her university photography project, Kaur posted a series of photographs to Instagram depicting herself with menstrual blood stains on her clothing and bedsheets. Instagram removed the image to which Kaur wrote a viral critique of the company's actions. As a result of the incident, Kaur's poetry gained more traction and her initially self-published debut collection, Milk and Honey (2014), was reprinted to widespread commercial success.

The success of Milk and Honey proved worrisome for Kaur as she struggled throughout the creation of the follow-up, The Sun and Her Flowers (2017). Feelings of burnout occurred after the release but soon subsided. A desire to feel less pressure for commercial success influenced her third collection, Home Body (2020) – a partial response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Considered to be a part of the "Instapoetry" group, Kaur's work is simplistic in nature and explores South Asian identity, immigration and femininity; her childhood and personal life serve as sources of inspiration. Line drawings accompany her poetry with stark subject matters.

Her popularity has been compared to that of a popstar and Kaur has been praised for influencing the modern literary scene, although Kaur's poetry has had mixed critical reception and been subject to frequent parody; she has been dogged by claims of plagiarism by fellow "Instapoets" and harassment by internet trolls. Kaur has been included on congratulatory year-end lists by the BBC and Elle; The New Republic controversially called her the "Writer of the Decade".

Early life[]

Kaur was born into a Sikh family in Punjab, India, on 5 October 1992.[2][3][4] At age three, she immigrated to Canada with her parents to avoid persecution of Sikhs.[5] Her father had left before, due to hate crimes against Sikh men and wasn't present for Kaur's birth.[6][7] Due to financial instability, he would send back supplies suitable for Kaur and her upbringing.[7] She lived with her parents and three younger siblings in a one-bedroom basement flat, where they slept in the same bed.[5] Her family eventually settled in Brampton, alongside a large South Asian community and Kaur's father, who worked as a truck driver.[2][6][8]

When her father lived in Japan he'd write poetry to Kaur's mother who practiced painting.[9] Kaur recalled that poetry was a recurrent aspect of her faith, spirituality and everyday life: "There were evenings when my dad would sit around for hours, analyzing a single verse for hours".[10] As a child, Kaur would find herself embarrassed by her mother's accent and try to distance herself.[11] Kaur was generally self-conscious about her identity.[10] Her mother was occasionally distant to Kaur, as a result of her family and culture, particularly when Kaur was on her period; menstruating, alongside her childhood abuse, often left her debilitated.[12] Her relationship with her parents, in particular her mother, become turbulent in her adolescence.[13] As a young child she witnessed relatives and friends experience domestic violence or sexual abuse.[14] Her environment growing up led to her developing what she deemed "constant survival mode".[15]

She performed kirtan and Indian classical music for several years and hoped to be a fashion designer – although her father refused her to pursue it in education.[9][16][12] Kaur also aspired to be an astronaut, or a social worker, her ambitions frequently changing.[17] She expressed an interest in reading from a young age – cutting and pasting words in tandem with images, and embellishing poems with drawings, finding it relieved her loneliness. Her interest was hindered by Kaur having English as a second language, first learning it at age 10.[5][9][18]

An initial aversion to English meant Kaur was effectively mute for a period of time.[19] Throughout middle school she partook in "speech competitions", winning one in seventh grade, thus helping her find progress and hope in spite of isolation and bullying.[16][17] According to Kaur, she was an easy target for ridicule due to her outward appearance and vulnerability.[20] She had began to grow in confidence following sixth grade and it was writing and performing that led her to "[find] her voice".[8][21] She experienced the nadir of her education during high-school, as she sustained, what she considered, toxic care. Her feelings were relieved upon forgoing people who she described as "very dangerous for me".[22]

She studied rhetoric and professional writing at the University of Waterloo; she'd teach creative-writing classes for high school and college students while in education herself.[2][3] When studying poetry she'd "agonize over each and every word", "I would have to pull out the list of literary devices my teacher gave me and my 10 colorful pens. It was like doing surgery on the damn thing".[11]

Career[]

Early work (2009–2013)[]

Kaur first began performing poetry in 2009.[23] Although she found spoken-word poetry "really natural", describing her first show as "Like a damn hug", she'd fidget with the paper above her face, leaving before audiences clapped due to her anxiety.[9][24] Her poetry at first received a lukewarm reception, having being told that she was too aggressive for certain venues or made some people uncomfortable.[5][25] "So many people around me early on thought it was absolutely ridiculous".[26] Kaur started writing in an attempt to articulate her personal trauma, having just left an abusive relationship – which influenced her decision to perform poetry.[27][28] At university, her writing became more reflective than before, having previously written about boys she liked and the political changes she wanted to see in the world.[29]

Throughout high school, Kaur shared her writing anonymously.[17] She took the stage surname of Kaur because "Kaur is the name of every Sikh woman – brought in to eradicate the caste system in India – and I thought, wouldn't it be empowering if a young Kaur saw her name in a book store?".[12][a] From 2013 onward, she began sharing her work without a pseudonym on Tumblr before moving to Instagram in 2014 where she started adding simple illustrations.[17] Around this time, she began to garner a cult following and, at times, had 600 attendants at her shows.[31][32] Her first poem posted on Instagram regarded a wife coping with her husband's alcoholism.[33] She described the experience as cathartic.[33]

Milk and Honey (2014–2016)[]

Following failed submissions to literary anthologies, magazines and journals, Kaur's first book, Milk and Honey, was self-published on Createspace on 4 November 2014, after she begun work at age 18.[2][11][25][34] She created the poems in Milk and Honey "entirely for [herself], with zero concept of book in mind", and sold more than 10,000 copies.[35][36] Kaur recalled that she was hesitant to submit to magazines or journals because it "felt like I was taking apart [Milk and Honey] and throwing things at different walls, hoping they would stick. I feel like it only made sense when it was [collected] because this is a body of work".[32]

In March 2015, as a part of her university photography project, Kaur – intending to challenge prevalent societal menstrual taboos and the objectification of women – posted a series of photographs to Instagram depicting herself with menstrual blood stains on her clothing and bed sheets.[27][37][38] Internet trolls harassed Kaur over the photos, which were twice removed for not complying with the site's terms of service; Kaur claimed that she was not notified beforehand or given a reason and criticised their censorship as misogynistic and reaffirming what she sought to condemn – deeming the act an "attack on my humanity".[37][39] Instagram apologized and brought back the images, citing a mistaken removal.[39]

Her response went viral, credited with bringing Kaur more followers and leading to the subsequent rise in popularity of her poetry.[11] She later regretted writing her response, finding widespread disdain affected her mental health, experiencing anxiety that "sort of set in and never really left" and suicidal thoughts for a period of time.[40][41] That same year, she wrote 10 chapters of a yet unpublished novel.[11]

As Kaur rose to prominence on social media, Milk and Honey was re-released by Andrews McMeel Publishing, which saw her work alongside an editor for the first time.[2] It became a "blockbuster" success and, as of 2017, has sold 2.5 million copies worldwide and translated into 25 languages – the same year, it was the best-selling book in Canada.[42][43] During a poetry reading in 2015, Kaur, upon seeing a line of her fans that extended four street blocks, fully realised the extent of her audience and grew more confident in her poetry as a result.[25] She performed a TED Talk the next year.[44] Kirsty Melville, publisher and president of AMP, credits the book's success with Kaur's connection to her readers.[45]

At age 22, she employed seven people to aid her, as a part of a company she founded.[46] After meeting her business partner, she became more calculated, particularly regarding her time management and public relations – having before responded to every comment on her now deleted Tumblr page.[46] While writing, her team often manages her social media.[47]

The Sun and Her Flowers (2017–2019)[]

they convinced me

i only had a few good years left

before i was replaced by a girl younger than me

as though men yield power with age

but women grow into irrelevance

they can keep their lies

for i have just gotten started

i feel as though i just left the womb

my twenties are the warm-up

for what i'm really about to do

wait till you see me in my thirties

now that will be a proper introduction

to the nasty, wild, woman in me,

how can i leave before the party's started

rehearsals begin at forty

i ripen with age

i do not come with an expiration date

and now

for the main event

curtains up at fifty

let's begin the show

Timeless

Following a three-month writing trip in California, and in the same year as her induction into the Brampton Arts Walk of Fame, Kaur's second book, The Sun and Her Flowers, was published, on 3 October 2017.[5][48][49] She views it as a "one long continuous poem that goes on for 250 pages", "which while birthed in Instagram, is a concept that depends on being bound".[35] As of 2020, the book has sold upwards of a million copies and has been translated into multiple languages.[40] In 2018, she made nearly $1.4 million from poetry sales.[50] That same year, she performed at the Jaipur Literary Festival: "It was as if I had waited my whole life for this moment. It was my only show, where I wasn't nervous. The crowd was energetic."[51]

While touring the world, she experienced feelings of depression and anxiety.[52] The process of creating The Sun and Her Flowers and trying to replicate her success affected her mental health, reporting "furious 12-hour [writing] stretches" and 72-hour migraines.[52][53] She experienced months of writer's block and frustration at her work, ultimately calling its creation the "greatest challange of my life".[54][55] Following its release, she dealt with feelings of burnout – writing the poem "Timeless" in response.[46] These feelings began to subsided as she viewed them as transient – aided by Elizabeth Gilbert's Big Magic, which she said "saved my life".[46] By early 2019, she entered therapy to ease her depression and anxiety.[40]

That year, she was commissioned by Penguin Classics to write an introduction for a new edition of Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet, in anticipation of that book entering the public domain in the United States and performed at the London Book Fair.[56][57] Kaur considers Gibran an influence and has dubbed The Prophet her "life bible".[58][59]

Home Body (2020–present)[]

Kaur released her new poetry collection, entitled Home Body, on 17 November 2020.[60] The collection featured illustrations from Kaur and became one of the best-selling books of 2020.[60][61] Intent with feeling less pressure for commercial profit, Kaur reached out to fellow authors for guidance – having felt imposter syndrome during its creation due to Milk and Honey's success.[40][52] She begun work in 2018, during a time of depression.[41]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kaur moved back in to her parents' house in Brampton and began teaching workshops on Instagram Live, due to feelings of loneliness and fear and a desire to connect with her audience.[62] To her students, she emphasizes a natural and therapeutic approach to writing.[62]

She self-released a poetry special, Rupi Kaur Live, consisting of poetry readings and anecdotes accompanied by visuals and music, in April 2021, after it was turned down by streaming services.[63][64] Explaining the impetus, Kaur recalled her separation of performance and prose, attempting to hide the former, and how her eventual marriage of the two styles "in maybe 2016" allowed the show to occur.[63] In 2021, she is set to perform as a part of a tribute to Jack.[65]

Artistry and influences[]

As in Gurmukhi script, her work is written exclusively in lowercase,[66] using only the period as a form of punctuation; Kaur writes this way to honour the Punjabi language.[67] She said that she enjoys the equality of letters and that the style reflects her worldview.[17] The experience of learning English upon moving to Canada and studying poetry has influenced her writing style, subsequently tailoring her work to be accessible, particularly by readers learning English.[11][34] Kaur has emphasized her poetry's relation to South Asian culture – to the point that she's weary of Western readers fully understanding it.[6]

Her poems often conclude with either a final italicized line that either identify its audience or articulate its theme or her name.[2] In her article for The Globe and Mail, Tajja Isen described this as Kaur's "trademark move" and likened it to the use of a hashtag.[49] Kaur's style ranges from aphoristic, inspirational and confessional, although her poems aren't "100 percent autobiographical".[8][34] Her dad's activism, which included Kaur partaking in protests as a child, inspired the political nature of her poems.[10]

The writing process begins with her starting on paper and then transferring the "most promising" material to an extended Microsoft Word document.[46] It concludes after she has narrowed the poem to its main elements and she has received affrimation from her sister.[33] Across all her projects, she maintains "full creative control", contributing towards aspects such as the cover and minutiae of her books.[63] Kaur has said that she approaches her poetry like running a business and writes "to perform it", seeing the stage as where her ambitions are fully achieved.[68][69] Within the context of performance, her use of line breaks and periods represent where she would pause and where a new idea would be introduced, respectively.[58]

Her written poetry focus upon design, whereas her performances centre on rhyme, narrative and delivery.[47] She performs in a sing-song manner, at times alongside audience members.[58] Carol Muske-Dukes highlighted that, in being a "performative poet", Kaur continues a tradition of "the page enact[ing] [the performance] in the mind".[35] Elisa New spotlighted Kaur's proximity and similarities with spoken-word and hip-hop artists.[6]

Sparse line drawings accompany her poems – "acting as visual punctuations"– and have been compared to outsider art and "doodles...found in the margins of old school books".[11][18][70][71] The National Poetry Library noted that in Milk and Honey, they function like a graphic novel.[72] The style of drawing contiunes in The Sun and Her Flowers.[73] Her illustrations, juxatposed with the poems, are "striking" and "often disturbing", with one, for example, linking self-harm with despair.[71][74] Images that appear in her work include twisting bodies, crawling flowers, and fingers forming the shapes of hearts. Kaur explained that her style is intended to be recognisable and evoke a brand, akin to Apple's.[71] She creates them following their respective poem being written.[41]

Alongside her peers – Nayyirah Waheed, Lang Leav, Warsan Shire – and other "Instapoets", Kaur's plainspoken and free verse poetry is delivered in a "bite-size" manner – some poems only composing of one line.[42][75] With The Sun and Her Flowers, her poems expanded their length.[58] Kaur, who dislikes the term "Instapoet", has been said to belong to a "new generation of migrant writers, a generation who 'sits-in, tweets, posts and broadcasts'" and considered as possibly the "representative of an entire generation's values and ethos".[12][76][77] Kaur has said that she writes for "the generation that's reading my work...I am writing something that is believable to that generation".[71]

Tina Daheley and The New York Times' Gregory Cowles recognised a candid and lyrical nature in Kaur's poetry with Cowles saying that her "artless vulnerability [is] like a cross between Charles Bukowski and Cat Power".[78][79] Due to her usage of dry, open-ended, and colloquial language, Kaur has been said to break from and reject tradtional standards and features of poetry which are held in importance.[35][80][81] Matthew Zapruder, Becky Robertson of Quill & Quire and Kaur identified a universal quality in her work.[35][82][83]

Following Milk and Honey, she became more selective in regards to publishing her poetry online, having extensively showcased her work online unless embarrassed by the content.[16] "Over the years, I've distanced myself from it...When the numbers started to grow, I started to overthink things. I felt more pressure to be correct and perfect all the time".[84] Focusing upon "design, marketing, creative writing and branding", Kuar's Instagram account, with 3.5 million followers, fluctuates between photographs of Kaur and her poetry.[85] Using The Sun and Her Flowers as a base, her poetry special had an "ethereal nature-driven aesthetic", featuring large yellow flower petals around the stage and projected.[68][86] She refined her aethestic into a more stylised manner following the release of Beyoncé (2013).[87][b]

Themes and motifs[]

our work should equip

the next generation of women

to outdo us in every field

this is the legacy we'll leave.

Progess, an example of Kaur's feminist writing.[75]

Taking inspiration from herself, her friends and her mother, her poetry explores a small selection of themes alongside issues faced by Indian women and immigrants, female trauma and the "South Asian experience".[11][27][42][88] Her mother is a subject she treats with reverence in her work and pays tribute to her parents in her poem Broken English.[89][86][c] Although examined differently, her written and performed poetry share the same themes.[47]

Domestic and sexual violence were a particular focus of her initial work and rape related trauma became more explicit after Milk and Honey.[16][90] She explored violence and trauma heavily in her early work because "[she] had this desire to unpack so many deeper emotions and issues that [she'd] seen affecting [her] and so many women around [her]".[31] Her poem, I'm Taking My Body Back, concerns her surviving a sexual assault.[91] Kaur has admitted that writing about these heavy subjects can be both cathartic and troublesome to her mental wellbeing.[92]

Kaur makes use of common cultural metaphors and motifs (e.g. honey, fruit, water).[76] Milk and Honey has themes of abuse, love, loss and healing.[75] Love serves as her general primary theme.[4] Feminism, refugees, immigration and her South Asian identity became more prominent in The Sun and Her Flowers, alongside musings on body dysmorphia, abuse, rape and self-love.[11][53][88] Kaur said of the books that they're are "inward" and "outward" journeys, respectively; The Sun and Her Flowers has more breadth of themes.[73][93] Influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, Home Body examines themes of capitalism, productivity and mental health, more than before.[52]

Reception and impact[]

fall in love with your solitude

Kaur's most popular poem, from Milk And Honey.[85]

The most popular of the "Instapoets", and dubbed the "Oprah of her generation," Chiara Giovanni of Buzzfeed News noted that Kaur's celebrity – which has led her peer Kazim Ali to call her perhaps the most famous poet of all time – is "more akin to that of a pop star like [Ariana] Grande than a traditional poet", crediting her accessibility.[75][94][95] Agatha French, writing for the Los Angeles Times, compared reactions to the announcement of The Sun and Her Flowers, by Kaur's majority young and female fans, to "the fervent devotion of Beatles fans".[18][35] Her live performances routinely have hundreds of attendees, with turnout, at times, as high as 800 people.[8][36]

According to Kaur, her success – which influenced a greater focus on poetry by booksellers, American adults and young people – has "democratised poetry and literature in general".[48][52][93][96][d][e] Regarded as a "pioneer" of the "Instapoet" style, Erica Wagner noted Kaur's influence in what she called the "biggest overall shift [in reading habits] we've seen in the past decade".[72][100] Fans have praised her for writing about her personal trauma and elevating diversity in a "overwhelmingly" white literary scene.[11][75][f] Her poetry has been credited with "inspir[ing] [a] hub of creativity for young black girls"; author Tanya Byrne argued that fellow BAME writers should replicate Kaur's self-publishment.[101][102] Kanwer Singh has described Kaur as an inspiration.[103] Nepalese-American fashion designer Prabal Gurung emblazoned Kaur's poem women of colour onto a piece in his 2016 collection.[95]

Online reception[]

Her series of menstrual photographs elicited a "very" mixed reception.[104] She received death threats levied towards her, which led to emotional numbness and a subsequent distancing from social media.[105] In retrospect, Amika George, a British activist who campaigns against period poverty in the United Kingdom, credits Kaur's menstrual photographs with being the "catalyst for opening up the conversation about periods".[12] Allison Jackson of The World and Jane Helpern of i-D espoused similar notions in 2015.[106][107] Kaur noted an effect on her friends in Punjab, as they had frank discussions with their families regarding periods.[12] In response to the reception of her photos, Kaur initially said:

I know that 50-60% of all comments on every site that covered the story were negative, but that didn't affect me much. What upset me was that people I knew first-hand were reacting badly. These were guys from my own community, who I'd been to high school with, and they were trying to tarnish me rather than the art...People always say my work is so great for women, that it is feminist art. But for me, it's men that need to see it the most. Because it's the misogyny that we need to address, rather than the feminism.[27]

Kaur later admitted that for many years internet trolls had "left me broken", having previously dismissed similar notions.[46] To resolve her dismay, she came to the conclusion that " I'm here to speak my truth and connect with readers, and that's it. None of the negative voices matter in the end".[46] Her work have been the subject of memes online, usually in the form of parody poems mocking Kaur's writing style, their promience having been compared to a cottage industry.[108][109] In 2017, a book parodying Kaur's poetry, entitled Milk and Vine, was released.[110]

Critical reception[]

Critics have been less laudatory than general audiences; she has become "something of a polarizing figure in the literary, publishing, and media communities", whose "work is often knocked as being lowbrow or trite, or not in the rich tradition of serious poetry".[48][111] Other criticisms include her work being formulaic, attenuated and without a lasting impact.[71][112] Kaur feels that her work can't be "fully reviewed or critiqued through a white lens or a Western one".[91] According to Ali, "no criticism has been leveled at Kaur that hasn't been similarly leveled at "actual" poets", citing Mary Oliver, Jane Hirshfield, Sharon Olds and Lucille Clifton.[94] Gregory Betts, similarly, said that Kaur "falls into a great literary tradition - extending back to Dante - of poets who were widely criticized for using the vernacular of their time".[113]

Rebecca Watts lambasted her poems' popularity and accessibility, describing them as "artless" and characterised by "the open denigration of intellectual engagement and rejection of craft" – Priya Khaira-Hanks, writing for The Guardian, remarked that Kaur's accessibility often led to "over-simplicity".[18][114][115][g] Isen disparaged what she regarded as an overly explanatory style, particularly when performed, as "the belated imposition of rhythm" fails to disclose compositional shortcomings.[49] Blair Crawford, of the Ottawa Citzen, felt that "In many ways her poems look like the type of glib aphorisms scribbled into the back of a high school yearbook, complete with XOs and hearts".[109]

Carl Wilson and Khaira-Hanks, argued that her mainstream success and personal identity contributed towards people disregarding her work.[18][34] The New York Times' Tariro Mzezewa rebuked the criticism that her poetry is inauthentic and co-opts other's experiences and rejected the notion that Kaur's work isn't "real literature".[42] Don Paterson said, in 2018, that "few poets consider [Kaur] a poet at all".[116] Speaking on Kaur's success and their similar topics, Muske-Dukes said that "I reach a couple thousand people and she reaches millions. I say more power to her".[35]

Waheed and Shire, among Kaur's influences, have accused her of plagiarism.[76] Claims by Waheed's supporters are based on Kaur and her lack of punctuation and use of honey as a metaphor.[117] Kaur has denied claims of plagiarism, speculating that their similar themes and use of honey is "by-product of our times".[91][108]

In 2017, BBC and Vogue listed Kaur in their lists of women of the year; Quill & Quire chose The Sun and Her Flowers for their annual list of the best books.[4][93][118] The next year she was included on Forbes and Elle's complimentary lists of emerging artists.[95][119] In 2019, The New Republic named Kaur "Writer of the Decade", due to her impact on the medium of poetry; this led to a debate on whether the award was deserved, as well as about her work in general.[70][76][96]

Works[]

Books[]

- Milk and Honey (2014)

- The Sun and Her Flowers (2017)

- Home Body (2020)

Articles[]

- "History shows Punjab has always taken on tyrants. Modi is no different". The Washington Post. 16 December 2020.

Performance films[]

- Rupi Kaur Live (2021)

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Kaur has described the name Singh as "the overarching last name" for her family.[30]

- ^ Kaur has listed Sharon Olds, Marina Abromovich, Adele, Beyoncé, Kahlil Gibran, Nizzar Qabbani, Amrita Sher-Gil and Frida Kahlo as influences.[10]

- ^ Kaur has explained that she feels that if her mother had not made significant sacrifices in Kaur's childhood than her career as a poet wouldn't have materlised.[89]

- ^ In Canada, Kaur was credited by industry analyst BookNet with an increase in poetry sales in 2017, and, in the United Kingdom, Kaur was also credited with an increase in poetry sales seen in 2017.[97][98]

- ^ Kaur also credits Instagram with the perceived democratsation of poetry, feeling that her working class and racial background wouldn't allow her to be published otherwise.[99]

- ^ The lack of distinction between personal and collective trauma has received criticism.[75]

- ^ Watt's criticism was supported and disparaged by poets alike.[115]

References[]

- ^ "Beyond Words". University of Waterloo. University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Fischer, Molly (3 October 2017). "The Instagram Poet Outselling Homer Ten to One". The Cut. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aguiar, Deborah Vieira Pinto; Magaldi, Carolina Alves (30 January 2020). "Rupi Kaur: Women's Writing Tradition in Translation". International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation. 3 (1). doi:10.32996/ijllt.2020.3.1.6. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pike, Naomi (29 December 2017). "The Girls Who Ruled 2017". British Vogue. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Fishwick, Samuel (5 May 2017). "Rupi Kaur: 'I've never been more aware of my colour'". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rao, Sonia (11 October 2017). "Few read poetry, but millions read Rupi Kaur - The Boston Globe". Boston Globe. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 6:00-7:00.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Choe, Jaywon; Flock, Elizabeth (2 January 2018). "How poet Rupi Kaur became a hero to millions of young women". PBS. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gopal, Vivek (1 May 2018). "Pop-Poet Rupi Kaur Isn't Worrying About Being Unique". Vice. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bozinoski, Mónica (10 October 2019). "Rupi Kaur: "When we connect, we feel less alone"". Vogue. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Carlin, Shannon (21 December 2017). "Meet Rupi Kaur, Queen of the 'Instapoets'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Burgum, Becky; George, Amika (28 May 2019). "Rupi Kaur And Amika George: Two Teen Icons Taking On The World". Elle. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Tina Daheley (2 June 2018). "Rupi Kaur: Rewriting the Migration Narrative". The Cultural Frontline (Podcast). BBC. Event occurs at 2:30-2:38. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Vaz, Wynat (14 June 2017). "The Female Gaze: Rupi Kaur on The Freedom of Expression". Verve. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Tom Power (2 December 2020). "Rupi Kaur on Home Body, depression and the viral photo that changed her life". Q (Podcast). CBC Radio. Event occurs at 9:10 - 9:20. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Biedenharn, Isabella (13 October 2017). "Instagram sensation Rupi Kaur doesn't have social media on her phone". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Jain, Atishsa (22 October 2016). "A poet and rebel: How Insta-sensation Rupi Kaur forced her way to global fame". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Khaira-Hanks, Priya (4 October 2017). "Rupi Kaur: the inevitable backlash against Instagram's favourite poet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 9:30-9:35.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 12:20-12:30.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 9:40-10:00.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 13:00-13:40.

- ^ Marsh, Ariana (5 January 2018). "Rupi Kaur and Sloane Stephens's Success Stories Are Total Career Inspiration". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Shadrach Kabango (19 April 2016). "'Micropoet' Rupi Kaur nourishes readers with Milk and Honey". Q (Podcast). CBC Radio. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kassam, Ashifa (26 August 2016). "Rupi Kaur: 'There was no market for poetry about trauma, abuse and healing'". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Irving, John; VanderMeer, Jeff (7 September 2017). "Why Rupi Kaur loves Harry Potter". CBC Books. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Briscoll, Drogan. "Feminist Artist Rupi Kaur, Whose Period Photograph Was Removed From Instagram: 'Men Need To See My Work Most'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Tom Power (30 April 2021). "'Aren't we all just fighting to be resilient?': Rupi Kaur on womanhood, poetry and her new live show". Q (Podcast). CBC Radio. Event occurs at 1:18-1:28. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Kahanna, Priyanka (5 February 2019). "Incredible Indian Women Across the Globe". Vogue India. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Tom Power (2 December 2020). "Rupi Kaur on Home Body, depression and the viral photo that changed her life". Q (Podcast). CBC Radio. Event occurs at 15:40 - 15:50. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Szkutak, Rebecca (10 October 2017). "How Rupi Kaur used Instagram to transform poetry". Interview Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arora, Kim (27 January 2018). "There is resistance to Insta-poetry only because it is new: Rupi Kaur - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Vaz, Wyanet (3 August 2017). "Instagram Poets Who Took Our Hearts By Storm: Rupi Kaur". Verve. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wilson, Carl (15 December 2017). "Why Rupi Kaur and Her Peers Are the Most Popular Poets in the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g French, Agatha (12 October 2017). "Instapoet Rupi Kaur may be controversial, but fans and book sales are on her side". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kirch, Claire (6 December 2016). "PW Notables of the Year: Rupi Kaur". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Faust, Gretchen (2017). "Hair, Blood and the Nipple: Instagram Censorship and the Female Body". Digital Environments: Ethnographic Perspectives Across Global Online and Offline Spaces. Transcript Verlag. pp. 159–170. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Das, Nabina (2015). "Blood, Period: In many countries, especially in India, menstruation is a subject of taboo and stigma, which feeds the ego and pride of a misogynist society that objectifies and sexualises women". Economic and Political Weekly. 50 (16): 95–96. ISSN 0012-9976. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaybor, Jacqueline (11 November 2020). "Everyday (online) body politics of menstruation". Feminist Media Studies. 0 (0): 1–16. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1847157. ISSN 1468-0777. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Power, Tom (2 December 2020). "Rupi Kaur on Home Body, depression and the viral photo that changed her life". CBC Radio. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mathers, Joanna (21 December 2020). "Rupi Kaur: Meet Poetry's Defiant Darling". Viva. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mezezwa, Tariro (5 October 2017). "Rupi Kaur Is Kicking Down the Doors of Publishing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Here are the bestselling books in Canada of 2017". CBC Books. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Writer, The Indian Express (4 October 2019). "Rupi Kaur weaves a powerful narrative on human trauma and healing". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Gross, Anisse (26 August 2016). "How To Sell Nearly a Half-Million Copies of a Poetry Book". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Maitland, Hayley (14 March 2019). "Instagram Sensation Rupi Kaur Gets Candid About Trolls, Acne, And How To Make It As A Writer". British Vogue. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Keswani, Sumeet (5 June 2016). "Men must read feminist poetry to know what we go through: Rupi Kaur". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Maher, John (2 February 2018). "Can Instagram Make Poems Sell Again?". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Isen, Tajja (27 April 2018). "Poet Rupi Kaur comes full circle with Brampton performance". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Ferguson, Donna (26 January 2019). "'Keats is dead...': How young women are changing the rules of poetry". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Bali, Etti (17 February 2018). "What Rupi Kaur heard while growing up: 'Can't you just fit in? Eww, you are so Indian!'". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Joshi, Sonam (13 December 2020). "Everyone said the literary world would laugh at me but I didn't care: Rupi Kaur - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Medley, Mark (6 October 2017). "Rupi Kaur: The superpoet of Instagram". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Shelagh (9 October 2017). "How Rupi Kaur pushed through writer's block to create her second collection of poems". CBC Radio. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 22:30-22:40.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (29 December 2018). "New Life for Old Classics, as Their Copyrights Run Out". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Albanese, Andrew (15 March 2019). "London Book Fair 2019: Heard Any Good Poems Lately?". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Shaikh, Sadaf (23 April 2018). "The Time Of Rupi Kaur In The Era Of A Vexed Generation". Verve. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Writer, CBC (10 October 2017). "Rupi Kaur and Shelagh Rogers share some of their favourite books of poetry". CBC Books. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Rupi Kaur to publish new poetry collection, home body, in Nov. 2020". CBC Books. 14 September 2020. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Isaac, Paulina Jayne (11 December 2020). "Here Are the Best-Selling Books of 2020". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "When COVID-19 hit, bestselling poet Rupi Kaur had writer's block — so she started teaching on Instagram". CBC Radio. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Rupi Kaur Self-Releases Poetry Special After Being Turned Down By Streaming Services: 'A Journey'". PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Bestselling poet Rupi Kaur releasing on-demand poetry performance film on April 30". CBC Books. 13 April 2021.

- ^ Staff, The Canadian Press (18 July 2021). "Star-studded event to mark 10th anniversary of Jack Layton's death". CTV News. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ VanderBeek, Conner Singh (2 April 2020). "To be a child of diaspora: The irreconcilable outsider in Sikh discourse". Sikh Formations. 16 (1–2): 187–199. doi:10.1080/17448727.2018.1545192. ISSN 1744-8727. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ O'Donnell, Norah (26 February 2018). "Rupi Kaur on the simplicity of her poetry and the rise of "Instapoets"". CBS News. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harumi, Luana (30 April 2021). "Rupi Kaur Wants To Give You Hope". V Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Hill, Faith; Yuan, Karen (15 October 2018). "How Instagram Saved Poetry". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alam, Rumaan (23 December 2019). "Rupi Kaur Is the Writer of the Decade". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Writer, The Economist (1 November 2017). "Rupi Kaur reinvents poetry for the social-media generation". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New to Eloans: Tracy K. Smith and Rupi Kaur". National Poetry Library. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cerón, Ella (4 October 2017). "Rupi Kaur Talks "The Sun and Her Flowers" and How She Handles Social Media's Response to Her Work". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Dean, Michelle (26 February 2016). "Instagram poets society: selfie age breeds life into verse and has a new following". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Giovanni, Chiara (4 August 2017). "The Problem With Rupi Kaur's Poetry". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ahsan, Sadaf (2 January 2020). "Rupi Kaur may not be MY 'writer of the decade,' but that doesn't mean she isn't THE 'writer of the decade'". National Post. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Harris, Ashleigh (3 July 2018). "Introduction: African Street Literatures and the Global Publishing Go-Slow". English Studies in Africa. 61 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1080/00138398.2018.1540173. ISSN 0013-8398.

- ^ Cowles, Gregory (17 June 2016). "Inside the List". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Tina Daheley (2 June 2018). "Rupi Kaur: Rewriting the Migration Narrative". The Cultural Frontline (Podcast). BBC. Event occurs at 1:36-1:38. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Castillo, Rafael (16 January 2020). "2020 will be the year of the independent author". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Euse, Erica (7 November 2017). "the cult of rupi kaur". i-D. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Becky (15 December 2016). "Q&Q staff share their holiday-gift picks". Quill & Quire. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 21:10-21:13.

- ^ Popa, Maya C. (29 March 2019). "What Happens When Verse Goes Viral?". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leszkiewicz, Anna (6 March 2019). "Why are we so worried about "Instapoetry"?". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "With an essential worker father and Brampton beset by COVID-19, poet Rupi Kaur celebrates the immigrant working class". Toronto Star. 28 April 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Writer, Times of India (8 February 2018). "Beyonce changed my life: Rupi Kaur - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Imran, Muhammad (2018). "The Sun and Her Flowers: Rupi Kaur. Kansas: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2017, 248 pages" (PDF). Asian Women. 34 (4): 121–124. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tina Daheley (2 June 2018). "Rupi Kaur: Rewriting the Migration Narrative". The Cultural Frontline (Podcast). BBC. Event occurs at 2:40-2:50. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Noel-Tod, Jeremy (15 October 2017). "Book review: The Sun and Her Flowers by Rupi Kaur". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Majumdar, Anushree (4 February 2018). "Rupi Kaur: The attractive, marketable social media icon critics love to rage at and young Instagrammers flock to". The Indian Express. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 25:00-26:00.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robertson, Becky (11 December 2017). "2017 Books of the Year: reviewers' picks | the sun and her flowers". Quill and Quire. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ali, Kazim (23 October 2017). "On Instafame & Reading Rupi Kaur by Kazim Ali". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pitt, Helen (1 November 2019). "Thought poetry was dead? The 'Instapoets' raking it in online would beg to differ". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weaver, Jackson (1 January 2020). "Instapoet Rupi Kaur's 'writer of the decade' honour rekindles debate on her work, genre". CBC Books. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Walker, Rob (7 October 2017). "'Now it's the coolest thing': rise of Rupi Kaur helps boost poetry sales". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Wong, Jessica (16 December 2018). "Viral verse: Poets of Instagram inject new life, fresh voices into poetry genre". CBC News. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Sam (20 March 2019). "The Rise Of The Insta-Poet: 6 Modern Bards You Should Be Following". British Vogue. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Wagner, Erica (10 December 2019). "How reading has changed in the 2010s". BBC Culture. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Devaney, Susan (27 November 2020). "Rupi Kaur's Poetry Inspired This Hub Of Creativity For Young Black Girls". British Vogue. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Byrne, Tanya (18 August 2017). "'BAME writers must tell their own stories – and we have to be disruptive'". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Koeverden, Jane Van (28 April 2017). "5 poets that inspire Humble The Poet". CBC Books. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Saul, Heather (31 March 2015). "Menstruation-themed photo series artist 'censored by Instagram' says images are to demystify taboos around periods". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Hutcheon, Jane (25 May 2017). One Plus One: Rupi Kaur (Video). One Plus One. ABC News. Event occurs at 19:00-19:20.

- ^ Jackson, Allison (2015). "These female artists are challenging the world's perception of women's bodies". The World. Public Radio International. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Helpern, Jane (1 July 2015). "10 signs that menstruation is modernizing". i-D. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Why Do We Love To Hate and Meme Insta-Poet Rupi Kaur?". www.vice.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crawford, Blair (17 November 2017). "Rupi Kaur, the 'Poet of Instagram' wows sellout crowd at Museum of History". . Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Kini, Aditi Natasha (15 November 2017). "White Mediocrity Has Propelled This Rupi Kaur Parody Book to the Top of the Best-Seller List". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Leeder, Karen (3 July 2018). "'I am a Double-voiced […] Bird': Identity and Voice in Ulrike Almut Sandig's Poetry". Oxford German Studies. 47 (3): 329–350. doi:10.1080/00787191.2018.1503471. ISSN 0078-7191. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Mann, Jagdeesh (9 June 2017). "Rupi Kaur's literary ascent is poetry in motion". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Bresge, Adina (8 June 2018). "Verse goes viral". The Hamilton Spectator. ISSN 1189-9417. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Carpani, Jessica (3 April 2021). "No rhyme or reason to publishers, says Britain's most followed poet on Instagram". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flood, Alison; Cain, Sian (23 January 2018). "Poetry world split over polemic attacking 'amateur' work by 'young female poets'". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Paterson, Don (26 January 2018). "Curses and verses: the spoken-word row splitting the poetry world apart". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "'Instapoet' Rupi Kaur weaves Punjab into her poems". Hindustan Times. 2 October 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ BBC Staff (1 November 2017). "BBC 100 Women 2017: Who is on the list?". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Casparis, Lena de (4 June 2018). "Introducing The Elle List 2018: 50 Movers And Shakers Of The Moment". Elle. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rupi Kaur |

| Library resources about Rupi Kaur |

| By Rupi Kaur |

|---|

- 1992 births

- 21st-century Canadian poets

- 21st-century Canadian women writers

- BBC 100 Women

- Canadian feminist writers

- Canadian people of Punjabi descent

- Canadian Sikhs

- Canadian spoken word poets

- Canadian women poets

- Indian emigrants to Canada

- Indian feminist writers

- Indian feminists

- Indian women poets

- Instagram poets

- Living people

- People from Brampton

- People involved in plagiarism controversies

- Poets from Punjab, India

- Punjabi-language poets

- Sikh feminists

- University of Waterloo alumni

- Women writers from Punjab, India

- Writers from Ontario

- Writers from Punjab, India

- Writers who illustrated their own writing