Russian fairy tale

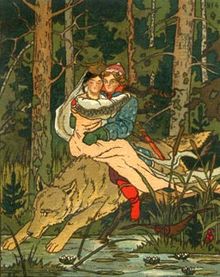

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; "story") is a fairy tale from Russia.

The term skazka can be used in many different forms to determine the type of tale or story being told. A volshebnaya skazka [fairy tale – волше́бная ска́зка] is considered a magical tale. Skazki o zhivotnykh [tales of animals] are tales about animals, and bytovye skazki [household tales] are tales about everyday life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail the different types of fairy tales.

Similarly to Western European tradition, especially the German collection, published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. His compendium is still referred to by folklore scholars when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories describing the stages of their plots and classification of the characters based on their functions was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century by Vladimir Propp.

History[]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[1] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[2]

The Communism Effect[]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[2] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in 's Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev's The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[3] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian's passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[4] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences on Russian Fairy Tales[]

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[5] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[6]

Cultural influences on Russian Fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don't ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man's follies and mistakes, others appear pointless." They were created to entertain the reader.[7]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play's choreography from its Russian background.[8]

Russian Formalism[]

In the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia called Russian Formalism. The term Russian formalism originated from critics of the new school of thought.[9]

Morphology[]

Analysis[]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[10][11] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[11]

Motif Analysis[]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the "simplest narrative unit."[12] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson's approach to folkloristics.[13] Thompson's research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[14]

Structural Analysis[]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled "The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style".[12] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[15] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, "It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata."[12]

Syntagmatic analysis, most notably championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[16] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[15] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky's definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[6] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[6][17] This methodology gives rise to Propp's 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[17] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[6]

, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled "The Morphological Study of Folklore", Nikiforov states that "Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable."[12] Since Nikiforov's essay was written almost 2 years before Propp's publication of Morphology of the Folktale[18], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[19] However, some sources claim that Nikiforov's work was "not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics" and failed to "keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts".[16] Nikiforov's work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[18]

Writers and collectors[]

Alexander Afanasyev[]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[20] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[21]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm's Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[20]

Alexander Pushkin[]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[22] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[23] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[24]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[25] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[26]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[27]

Tale corpus[]

According to scholarship, some of "most popular or most significant" types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][29]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre's (Devil's) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [b] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | ||

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [c] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil's Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [d] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [e] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | [f] | |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [g][h] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [i] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [j] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [k] |

Footnotes[]

- ^ Propp's The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[28]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing "throughout Europe", is well known in Russia, where it found "its favorite soil".[30]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch "[is] common among the various East European peoples."[31]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is "especially common in Russia".[32]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) "belongs to the core of" the Russian tale corpus, due to "the presence of numerous variants".[33]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type "is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic".[34]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is "common among the East Slavs".[35]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is "very common in all the East Slavic traditions".[37]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is "a very common East Slavic type".[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is "especially common in Russian and Ukrainian".[39]

References[]

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). "Fairy Tales in Society's Service". Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). "Russian Fairy Tales". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). "'The Sleeping Beauty' Review: Back to Its Russian Roots". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). "Russian Formalism". Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). "The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique". Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. "What is a Folklore Motif?". www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). "AN OUTLINE OF PROPP'S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES" (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). "Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union". Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). "Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book".

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. "Fairy Tales in Society's Service." Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Delarue, Paul Delarue. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). "Сказка "слепой и безногий" (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета". Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 - Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. "Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)". In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

External links[]

- Russian literature

- Russian fairy tales