Saco, Maine

Saco, Maine | |

|---|---|

City | |

View of Main Street | |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): | |

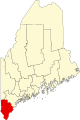

Location of city of Saco in Maine | |

Saco, Maine Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 43°30′38″N 70°26′42″W / 43.51056°N 70.44500°WCoordinates: 43°30′38″N 70°26′42″W / 43.51056°N 70.44500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maine |

| County | York |

| Incorporated (district) | June 9, 1762 |

| Incorporated (town) | August 23, 1775 |

| Incorporated (city) | February 18, 1867 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bill Doyle |

| Area | |

| • Total | 52.76 sq mi (136.64 km2) |

| • Land | 38.59 sq mi (99.93 km2) |

| • Water | 14.17 sq mi (36.71 km2) |

| Elevation | 66 ft (20 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 18,482 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 19,964 |

| • Density | 517.40/sq mi (199.77/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 04072 |

| Area code(s) | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-64675 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0574646 |

| Website | www.sacomaine.org |

Saco /ˈsɑːkoʊ/ is a city in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 18,482 at the 2010 census. It is home to Ferry Beach State Park, Funtown Splashtown USA, Thornton Academy, as well as General Dynamics Armament Systems (also known by its former name, Saco Defense), a subsidiary of the defense contractor General Dynamics. Saco sees much tourism during summer months due to its amusement parks, Ferry Beach State Park, and proximity to Old Orchard Beach.

Saco is part of the Portland–South Portland–Biddeford, Maine metropolitan statistical area. Saco's twin-city is Biddeford.

History[]

This was territory of the Abenaki tribe whose fortified village was located up the Sokokis Trail at Pequawket (now Fryeburg). There was a settlement at the mouth of the Saco river, with homes and permanent cultivation, at the time of contact with Europeans in the early 1600s.[4]

In July 1607, 500 warriors led by sakmow (Grand Chief) of the Mi'kmaq First Nations Henri Membertou attacked the village at present-day Saco, killing 20 of their braves, including two of their leaders, Onmechin and Marchin, leading to conflict that lasted until 1615.[5]

In 1630 the Plymouth Company granted Thomas Lewis and Richard Bonython a charter to establish a town at Saco, with a deed that extended 4 miles (6.4 km) along the sea, by 8 miles (13 km) inland. Settled in 1631 as part of Winter Harbor (as Biddeford Pool was first known). The government of Maine, under Ferdinando Gorges, was based in the town from 1636 to 1653.[6] It would be reorganized in 1653 by the Massachusetts General Court as Saco, which would be renamed Biddeford in 1718.[7][8]

The settlement was attacked by Indians in 1675 during King Philip's War. Settlers moved to the mouth of the river, and the houses and mills they left behind were burned. Saco lay in contested territory between New England and New France, which recruited the Indians as allies. In 1689 during King William's War, it was again attacked, with some residents taken captive. Hostilities intensified from 1702 until 1709, then ceased in 1713 with the Treaty of Portsmouth. The community was rebuilt and in 1718 incorporated as Biddeford. Peace would not last, however, and the town was again attacked in 1723 during Dummer's War, when it contained 14 garrisons. In August and September 1723, there were Indian raids on Saco, Maine and Dover, New Hampshire.[9] But in 1724, a Massachusetts militia destroyed Norridgewock, an Abenaki stronghold on the Kennebec River organizing raids on English settlements. The region became less dangerous, especially after the French defeat in 1745 at the Battle of Louisburg. The French and Indian Wars finally ended with the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[7]

In 1762, the northeastern bank of Biddeford separated as the District of Pepperrellborough, named for Sir William Pepperrell, hero of the Battle of Louisburg and late proprietor of the town. Amos Chase was one of the pioneers of Pepperrellborough. He was chosen as a selectman at the first town meeting, and served as the first deacon of the Congregational Church. Dea. Chase was one of the area's largest taxpayers, and was prominent in civic affairs during the American Revolution, serving on the town's Committee of Correspondence and Committee of Inspection.[10]

The district was incorporated as the Town of Pepperellborough in 1775. Inhabitants found the name to be cumbersome, so in 1805 it was renamed Saco. It would be incorporated as a city in 1867.[6][11] Saco became a center for lumbering, with log drives down the river from Little Falls Plantation (now Dayton, Lyman, Hollis and part of Limington). At Saco Falls, the timber was cut by 17 sawmills. In 1827, the community produced 21,000,000 feet (6,400,000 m) of sawn lumber, some of which was used for shipbuilding.[12]

On Factory Island, the Saco Iron Works began operation in 1811. The Saco Manufacturing Company established a cotton mill in 1826, and a canal was dug through rock to provide water power. The mill burned in 1830, but was replaced in 1831 by the York Manufacturing Company. With the arrival of the Portland, Saco and Portsmouth Railroad in 1842, Factory Island developed into a major textile manufacturing center, with extensive brick mills dominating the Saco and Biddeford waterfronts. Other businesses included foundries, belting and harnessmaking, and machine shops. But the New England textile industry faded in the 20th century, and the York Manufacturing Company would close in 1958. The prosperous mill town era, however, left behind much fine architecture in the Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival and Victorian styles. Many buildings are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13]

In 1844, Laurel Hill Cemetery was established on 25-acre (10 ha) of land. Still in operation, it is one of the earliest examples of the Rural cemetery movement.

Saco has taken steps to make the city more environmentally friendly. In early 2007 a small wind turbine was erected near the water treatment plant at the foot of Front street. Another larger wind turbine was erected on the top of York Hill in December 2007, and was expected to generate power for the new train station for Amtrak's Downeaster, although this was torn down in 2018 as the wind turbine never came close to generating the amount of energy promised.[14] Saco also has two growing business parks.[15]

Amos Chase house on Ferry Road; built ca. 1743

York Manufacturing Co. in 1916

Civil War memorial in Eastman Park

Saco City Hall

Masonic Hall

Geography[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 52.76 square miles (136.65 km2), of which, 38.46 square miles (99.61 km2) of it is land and 14.30 square miles (37.04 km2) is water.[16] Situated beside Saco Bay on the Gulf of Maine, Saco is drained by the Saco River.

Saco borders the city of Biddeford, as well as the towns of Scarborough, Buxton, Dayton and Old Orchard Beach.

Terrain[]

Saco contains a wide variety of landforms, including beaches, fields, forests, bogs, and urban areas.

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 1,350 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,842 | 36.4% | |

| 1810 | 2,492 | 35.3% | |

| 1820 | 2,532 | 1.6% | |

| 1830 | 3,219 | 27.1% | |

| 1840 | 4,408 | 36.9% | |

| 1850 | 5,798 | 31.5% | |

| 1860 | 6,223 | 7.3% | |

| 1870 | 5,755 | −7.5% | |

| 1880 | 6,389 | 11.0% | |

| 1890 | 6,075 | −4.9% | |

| 1900 | 6,122 | 0.8% | |

| 1910 | 6,583 | 7.5% | |

| 1920 | 6,817 | 3.6% | |

| 1930 | 7,233 | 6.1% | |

| 1940 | 8,631 | 19.3% | |

| 1950 | 10,324 | 19.6% | |

| 1960 | 10,515 | 1.9% | |

| 1970 | 11,678 | 11.1% | |

| 1980 | 12,921 | 10.6% | |

| 1990 | 15,181 | 17.5% | |

| 2000 | 16,822 | 10.8% | |

| 2010 | 18,482 | 9.9% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 19,964 | [3] | 8.0% |

| sources:[17] | |||

2010 census[]

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 18,482 people, 7,623 households, and 4,925 families residing in the city. The population density was 480.6 inhabitants per square mile (185.6/km2). There were 8,508 housing units at an average density of 221.2 per square mile (85.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.7% White, 0.7% African American, 0.2% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.3% of the population.

There were 7,623 households, of which 28.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.2% were married couples living together, 10.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 35.4% were non-families. 27.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 41.9 years. 21.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.6% were from 25 to 44; 30.5% were from 45 to 64; and 14.3% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.3% male and 51.7% female.

2000 census[]

As of the census[18] of 2000, there were 16,822 people, 6,801 households, and 4,590 families residing in the city. The population density was 437.2 people per square mile (168.8/km2). There were 7,424 housing units at an average density of 193.0 per square mile (74.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.91% White, 0.32% African American, 0.15% Native American, 0.51% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.10% from other races, and 0.93% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.58% of the population.

There were 6,801 households, out of which 33.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.3% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.5% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.0% under the age of 18, 6.8% from 18 to 24, 32.1% from 25 to 44, 22.2% from 45 to 64, and 13.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $45,105, and the median income for a family was $52,724. Males had a median income of $35,446 versus $25,585 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,444. About 7.1% of families and 8.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.4% of those under age 18 and 10.8% of those age 65 or over.

Voter registration

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of March 2020[19] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 6,513 | 41.46% | |||

| Unenrolled | 4,994 | 31.79% | |||

| Republican | 3,627 | 23.09% | |||

| Green Independent | 574 | 3.65% | |||

| Total | 15,708 | 100% | |||

Saco is divided into 7 voting wards, represented by: Ward 1 Councilor Marshall Archer, Ward 2 Councilor Jim Purdy, Ward 3 Councilor Joseph Gunn, Ward 4 Councilor Michael Burham, Ward 5 Councilor Phillip Hatch, Ward 6 Councilor Jodi MacPhail, and Ward 7 Councilor Nathan Johnston. [20]

Education[]

List of schools[]

- Fairfield School (K-2)

- Young School (K-2)

- C.K. Burns School (3-5)

- Saco Middle School (6-8)[22]

- Thornton Academy (9-12)

- Thornton Middle School (6-8) - Arundel, ME student overflow from partner RSU, RSU 21

- Saco Transition Program (6-12)

- The School At Sweetser (1-12)

- Saco Island School (9-12)

Previous schools[]

- Notre Dame de Lourdes School (K-8) - Closed in 2009 due to budget constraints and lack of students.[23]

Higher education[]

- University College has a campus located in Saco.

Infrastructure[]

Transportation[]

The Saco Transportation Center provides transportation between Portland and Boston via the Downeaster passenger train.

Saco is accessible from Interstate 95, U.S. Route 1 and Interstate 195. State routes 5, 9, 112, and 117 also serve the city. Taxis serve the Tri-City Area (Saco, Biddeford, and Old Orchard Beach).

The Portland International Jetport is about 14 miles (23 km) north of Saco. The [24] and [25] provide local transportation.

Notable people[]

- Henry A. Barrows, actor[citation needed]

- Liberty Billings, Florida senator[26]

- Samuel Brannan, businessman and pioneer[27]

- Amos Chase, Saco pioneer[28]

- Justin Chenette, Maine state representative[29]

- Richard Cutts, U.S. congressman[30]

- Arthur P. Fairfield, naval officer[31]

- John Fairfield, U.S. congressman and senator; 16th governor of Maine[32]

- Rory Ferreira, musician better known as Milo[33]

- George Lincoln Goodale, botanist[34]

- Charles Henry Granger, painter[35]

- John Johnson, pioneer photographer and inventor.[36]

- Bryan Kaenrath, Maine state representative[37]

- Cyrus King, U.S. congressman[38]

- Slugger Labbe, crew chief with NASCAR[39]

- James Felix McKenney, actor[citation needed]

- Isaac Lawrence Milliken, 16th mayor of Chicago[40]

- Edith Nourse Rogers, U.S. congresswoman[41]

- Emery J. San Souci, 53rd governor of Rhode Island[42]

- John Fairfield Scammon, U.S. congressman[43]

- Ether Shepley, Maine state congressman, U.S. senator and jurist[44]

- George F. Shepley, general in the Union Army and 18th Governor of Louisiana[45]

- John Wingate Thornton, lawyer, historian, and author[46]

Sites of interest[]

- Dyer Library

- Funtown Splashtown USA

- Saco Heath Preserve

References[]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Champlain's Map of Saco Bay".

- ^ http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2536600069.html

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 976.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. pp. 288–290.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ^ Maine Resource Guide: Biddeford, York County

- ^ William Williamson, p. 123

- ^ Chase, Lonnie. "Chase-L Archives". listsearches.rootsweb.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Maine Places - Saco, York County". Maine Genealogy. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Varney, George J. (1886), Gazetteer of the state of Maine. Saco, Boston: Russell

- ^ Hardiman, Thomas. "A History of the Factory Island Mill District". Sacomaine.org. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014.

- ^ https://bangordailynews.com/2017/10/12/environment/maine-city-struggles-to-get-rid-of-windmill-that-never-produced-energy-as-promised/

- ^ Hardiman, Thomas. "An Introduction to Saco History". Sacomaine.org. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of March 4, 2020" (PDF). Maine Bureau of Corporations.

- ^ https://www.sacomaine.org/mayor_and_city_council/index.php

- ^ https://www.sacomaine.org/mayor_and_city_council/index.php

- ^ "saco.org". saco.org. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ http://bangordailynews.com/2011/06/17/news/portland/82-year-old-saco-catholic-school-closes/

- ^ "Shuttle Bus Service". Shuttelbuszoom.

- ^ "Zoom Bus Service". Shuttlebuszoom.

- ^ "Who was Liberty Billings?". fernandinaobserver.com.

- ^ "The Apostate Mormon". California Missions Resource Center. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "CHASE-L Archives". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Meet Justin: Legislator, Entrepreneur, Philanthropist". Chenette Media LLC. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "CUTTS, Richard, (1771 - 1845)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Delta Kappa Epsilon (1895). The Deke Quarterly, Volumes 13-14. Delta Kappa Epsilon. p. 212.

- ^ "FAIRFIELD, John, (1797 - 1847)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Martin, Andrew (July 23, 2013). "How the WWE and Nas Influence Rapper Milo". MTV Hive.

- ^ Marquis, Albert Nelson (1915). Who's who in New England: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the States of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. A.N. Marquis. p. 464.

George Lincoln Goodale saco maine.

- ^ "Granger, Charles HenryAmerican, 1812 - 1893". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Rinhart, Floyd; Rinhart, Marion (April 1977). "Wolcott and Johnson; Their Camera and Their Photography". History of Photography. Benezit Dictionary of Artists (Oxford University Press): 99–109, 129–134.

- ^ "Bryan Kaenrath is Saco's new city administrator". Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "KING, Cyrus, (1772 - 1817)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Slugger Labbe's long, winding road paying dividends with Paul Menard, Richard Childress Racing". Sportingnews.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Mayor Isaac Lawrence Milliken Biography". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "ROGERS, Edith Nourse, (1881 - 1960)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ McLoughlin, William (1986). Rhode Island: A History (States and the Nation). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 184. ISBN 9780393302714.

- ^ "Scamman, John Fairfield, (1786-1858)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "SHEPLEY, Ether, (1789 - 1877)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2013). American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [6 volumes]: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 1761. ISBN 9781851096824.

- ^ New England Historic Genealogical Society (1907). Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Towne Memorial Fund. The Society. p. 294.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saco, Maine. |

- Saco, Maine

- Cities in York County, Maine

- Populated places established in 1631

- Portland metropolitan area, Maine

- Cities in Maine

- Populated coastal places in Maine

- 1631 establishments in the Thirteen Colonies