Sambucus

| Sambucus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sambucus berries (elderberries) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Dipsacales |

| Family: | Adoxaceae |

| Genus: | Sambucus L.[1] |

| Species | |

Sambucus is a genus of flowering plants in the family Adoxaceae. The various species are commonly called elder or elderberry. The genus was formerly placed in the honeysuckle family, Caprifoliaceae, but was reclassified as Adoxaceae due to genetic and morphological comparisons to plants in the genus Adoxa.

Description[]

The oppositely arranged leaves are pinnate with 5–9 leaflets (or, rarely, 3 or 11). Each leaf is 5–30 cm (2.0–11.8 in) long, and the leaflets have serrated margins. They bear large clusters of small white or cream-colored flowers in late spring; these are followed by clusters of small black, blue-black, or red berries (rarely yellow or white).

Color[]

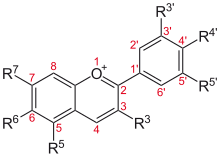

Elderberries are rich in anthocyanidins[3] that combine to give elderberry juice an intense blue-purple coloration that turns reddish on dilution with water.[4] These pigments are used as colorants in various products,[3] and "elderberry juice color" is listed by the US FDA as allowable in certified organic food products.[3] In Japan, elderberry juice is listed as an approved "natural color additive" under the Food and Sanitation Law.[5] Fibers can be dyed with elderberry juice (using alum as a mordant)[6] to give a light "elderberry" color[clarify].

Toxicity[]

Although the cooked berries (pulp and skin) of most species of Sambucus are edible,[7][8] the uncooked berries and other parts of plants from this genus are poisonous.[9] Leaves, twigs, branches, seeds, roots, flowers, and berries of Sambucus plants produce cyanogenic glycosides, which have toxic properties.[9] Ingesting a sufficient quantity of cyanogenic glycosides from berry juice, flower tea, or beverages made from fresh leaves, branches, and fruit has been shown to cause illness, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and weakness.[7][9][10] In August 1983, a group of 25 people in Monterey County, California, became suddenly ill by ingesting elderberry juice pressed from fresh, uncooked Sambucus mexicana berries, leaves, and stems.[10] The density of cyanogenic glycosides is higher in tea made from flowers (or leaves) than from the berries.[9][11]

The seeds of Sambucus callicarpa are poisonous and may cause vomiting or diarrhea.[12]

Taxonomy[]

The taxonomy of the genus Sambucus L., originally described by Carl Linnaeus and hence its botanical authority, has been complicated by its wide geographical distribution and morphological diversity. This has led to overdescription of the species and infraspecific taxa (subspecies, varieties or forms).[13] The name comes from the Greek word sambuce, an ancient wind instrument, about the removal of pith from the twigs to make whistles.[14]

Species recognized in this genus are:[15][16]

- – Himalaya and eastern Asia

- Sambucus australasica – New Guinea, eastern Australia

- Sambucus australis – South America

- – west coast of North America

- Sambucus canadensis – eastern North America

- Sambucus cerulea – western North America

- Sambucus ebulus – central and southern Europe, northwest Africa and southwest Asia

- Sambucus gaudichaudiana – south eastern Australia

- Sambucus javanica – southeastern Asia

- Sambucus lanceolata – Madeira Island

- – Korea, southeast Siberia

- – western North America

- – southwest North America

- Sambucus nigra – Europe and North America

- – western North America

- Sambucus palmensis – Canary Islands

- Sambucus peruviana – Costa Rica, Panama and northwest South America

- Sambucus pubens – northern North America

- Sambucus racemosa – northern, central and southeastern Europe, northwest Asia, central North America

- – eastern Asia

- Sambucus sieboldiana – Japan and Korea

- – southeastern United States

- Sambucus tigranii – southwest Asia

- Sambucus velutina – southwestern North America

- – western Himalayas

- – northeast Asia

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 305 kJ (73 kcal) |

18.4 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 7 g |

0.5 g | |

0.66 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 4% 30 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 6% 0.07 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.06 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 3% 0.5 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 3% 0.14 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 18% 0.23 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 2% 6 μg |

| Vitamin C | 43% 36 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 4% 38 mg |

| Iron | 12% 1.6 mg |

| Magnesium | 1% 5 mg |

| Phosphorus | 6% 39 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 280 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.11 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 79.80 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Distribution and habitat[]

The genus occurs in temperate to subtropical regions of the world. More widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, its Southern Hemisphere occurrence is restricted to parts of Australasia and South America. Many species are widely cultivated for their ornamental leaves, flowers, and fruit.[17]

Habitat[]

Elder commonly grows near farms and homesteads. It is a nitrogen-dependent plant and thus is generally found near places of organic waste disposal. Elders are often grown as a hedgerow plant in Britain since they take very fast, can be bent into shape easily, and grow quite profusely, thus having gained the reputation of being 'an instant hedge'. It is not generally affected by soil type or pH level and will virtually grow anywhere sufficient sunlight is available.

Ecology[]

In Northern California, elderberries are a food for migrating band-tailed pigeons. Elders are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species including brown-tail, buff ermine, dot moth, emperor moth, engrailed moth, swallow-tailed moth and the V-pug. The crushed foliage and immature fruit have a strong fetid smell. Valley elderberry longhorn beetles in California are very often found around red or blue elderberry bushes. Females lay their eggs on the bark.[18] The pith of elder has been used by watchmakers for cleaning tools before intricate work.[19]

Cultivation[]

Traditional uses of Sambucus involved berries, seeds, leaves, and flowers or component extracts.[20] Ornamental varieties of Sambucus are grown in gardens for their showy flowers, fruits and lacy foliage which support habitat for wildlife.[21] Of the many native species, three are used as ornamentals, S. nigra, S. canadensis and S. racemosa.[22]

Uses[]

Nutrition[]

Raw elderberries are 80% water, 18% carbohydrates, and less than 1% each of protein and fat (table). In a 100-gram (3.5 oz) amount, elderberries supply 73 calories and are a rich source of vitamin C, providing 43% of the Daily Value (DV). Elderberries also have moderate contents of vitamin B6 (18% DV) and iron (12% DV), with no other nutrients in significant content.

Dietary supplement[]

Elderberry fruit or flowers are used as dietary supplements to prevent or provide relief from minor diseases, such as flu, colds, constipation, and other conditions, served as a tea, extract or in a capsule.[7] The use of elderberry supplements increased early in the COVID-19 pandemic.[23] There is insufficient research to establish its effectiveness for such uses, or its safety profile.[7][23]

Traditional medicine[]

Although practitioners of traditional medicine have used elderberry over centuries,[21] there is no high-quality clinical evidence that such practices provide any benefit.[7]

Other[]

The flowers of Sambucus nigra are used to produce elderflower cordial. St-Germain, a French liqueur, is made from elderflowers. Hallands Fläder, a Swedish akvavit, is flavoured with elderflowers.

Hollowed elderberry twigs have traditionally been used as spiles to tap maple trees for syrup.[24] Additionally, they have been hollowed out and used as flutes, blowguns, and syringes.[25]

The fruit of S. callicarpa is eaten by birds and mammals. It is inedible to humans when raw but can be made into wine.[12]

Elderberry twigs and fruit are employed in creating dyes for basketry. These stems are dyed a very deep black by soaking them in a wash made from the berry stems of the elderberry.[21]

In popular culture[]

Folklore related to elder trees is extensive and can vary according to region.[26] In some traditions, the elder tree is thought to ward off evil and give protection from witches, while other beliefs say that witches often congregate under the plant, especially when it is full of fruit.[27] If an elder tree was cut down, a spirit known as the Elder Mother would be released and take her revenge. The tree could only safely be cut while chanting a rhyme to the Elder Mother.[28]

Made from the branch of an elder tree, the Elder Wand plays a pivotal role in the final book of the Harry Potter series, which was nearly named Harry Potter and the Elder Wand before author J. K. Rowling decided on Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[29][30]

Elton John's 1973 album Don't Shoot Me I'm Only the Piano Player features a song titled "Elderberry Wine".

In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, John Cleese as the French Taunter tells the knights of Camelot, "Your mother was a hamster, and your father smelt of elderberries."[31]

Gallery[]

Sambucus canadensis showing the complex branching of the inflorescence

Sambucus canadensis showing the inflorescence

Elderberry cultivation in Austria

References[]

- ^ "Sambucus L". Germplasm Resource Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2005-10-13. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Johnson, M. C; Thomas, A. L; Greenlief, C. M (2015). "Impact of Frozen Storage on the Anthocyanin and Polyphenol Content of American Elderberry Fruit Juice". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 63 (23): 5653–5659. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01702. PMC 4472577. PMID 26028422.

- ^ a b c Colors Derived from Agricultural Products, USDA

- ^ "National Organic Program (NOP)-Proposed Amendments to the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances (Processing)". Federal Register. May 15, 2007.

- ^ Processing Fruits: Science and Technology (Second ed.). CRC Press. 2004. pp. 322–324. ISBN 9781420040074. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ Burgess, Rebecca (2011). Harvesting Color: How to Find Plants and Make Natural Dyes. Artisan Books. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9781579654252. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "European elder". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. September 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ McVicar, Jekka (2007). "Jekka's Complete Herb Book" p. 214–215. Raincoast Books, Vancouver. ISBN 1-55192-882-5

- ^ a b c d Senica, M; Stampar, F; Veberic, R; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M (2016). "The higher the better? Differences in phenolics and cyanogenic glycosides in Sambucus nigra leaves, flowers and berries from different altitudes". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 97 (8): 2623–2632. doi:10.1002/jsfa.8085. PMID 27734518.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (April 6, 1984). "Poisoning from Elderberry Juice—California". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 33 (13): 173–174. PMID 6422238. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Viapiana, A; Wesolowski, M (2017). "The Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Infusions of Sambucus nigra L". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 72 (1): 82–87. doi:10.1007/s11130-016-0594-x. PMC 5325840. PMID 28084608.

- ^ a b Whitney, Stephen (1985). Western Forests (The Audubon Society Nature Guides). New York: Knopf. p. 423. ISBN 0-394-73127-1.

- ^ Applequist 2015.

- ^ Niering, William A.; Olmstead, Nancy C. (1985) [1979]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. Knopf. p. 448. ISBN 0-394-50432-1.

- ^ TPL 2013.

- ^ Eriksson & Donoghue 1997.

- ^ RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1-4053-3296-5.

- ^ "Asian Long-Horned Beetle Life Cycle, Development & Life Stages". Orkin.com. 2018-04-11. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

- ^ Materials used in construction and repair of watches

- ^ Gayle Engels; Josef Brinckmann (2013). "European elder, Sambucus nigra, L." HerbalGram, American Botanical Council. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Stevens M (2001). "Guide for common elderberry (Sambucus nigra L. ssp. Canadensis (L.)" (PDF). National Resources Conservation Service, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Boland 2012.

- ^ a b "Dietary Supplements in the Time of COVID-19: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. 5 October 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Medve, Richard J. et al. Edible Wild Plants of Pennsylvania and Neighboring States Penn State Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-271-00690-1, p.161

- ^ Lyle, Katie Letcher (2010) [2004]. The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants, Mushrooms, Fruits, and Nuts: How to Find, Identify, and Cook Them (2nd ed.). Guilford, CN: FalconGuides. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-59921-887-8. OCLC 560560606.

- ^ Diacono, Mark (15 June 2013). "In praise of the elderflower". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Jen Munson (25 October 2016). "Consider warding off witches, monsters with these spooktacular herbs this Halloween". The News-Herald, Digital First Media, Denver, CO. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Howard, Michael. Traditional Folk Remedies (Century, 1987); pp. 134–5

- ^ Groves, Beatrice (2017). Literary Allusion in Harry Potter. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 9781351978736. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Brown, Jen (30 July 2007). "Confused by Potter? Author sets record straight". TODAY. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Monty Python and the Holy Grail - Scene 8: Why No One Likes the French".

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Institutes of Health's National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health entry for European Elder

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: National Institutes of Health's National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health entry for European Elder

Further reading[]

- Applequist, W.L. (January 2015). "A brief review of recent controversies in the taxonomy and nomenclature of Sambucus nigra sensu lato". Acta Horticulturae. 1061 (1061): 25–33. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1061.1. PMC 4859216. PMID 27158181.

- Bolli, R. (1994). "Revision of the Genus Sambucus". Dissertationes Botanicae. 223.

- Donoghue, Michael J.; Eriksson, Torsten; Reeves, Patrick A.; Olmstead, Richard G. (2001). "Phylogeny and phylogenetic taxonomy of Dipsacales, with special reference to Sinadoxa and Tetradoxa (Adoxaceae)" (PDF). Harvard Papers in Botany. 6 (2): 459–479.

- Boland, Todd (15 September 2012). "Ornamental Elderberries". Dave's Garden. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- TPL (2013). "Sambucus". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sambucus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Sambucus. |

- Sambucus

- Berries

- Butterfly food plants

- Dipsacales genera

- Drought-tolerant plants

- Garden plants of North America

- Medicinal plants

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus