Sandefjord

Sandefjord kommune | |

|---|---|

| |

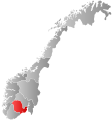

Coat of arms  Vestfold og Telemark within Norway | |

| Nickname(s): Hvalfangstbyen ("The Whaling City"), Badebyen ("The Bathing City") | |

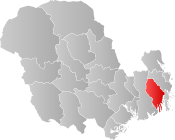

Sandefjord within Vestfold og Telemark | |

| Coordinates: 59°7′50″N 10°13′00″E / 59.13056°N 10.21667°ECoordinates: 59°7′50″N 10°13′00″E / 59.13056°N 10.21667°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Vestfold og Telemark |

| District | Vestfold |

| Administrative centre | Sandefjord |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2004–) | Bjørn Ole Gleditsch (H) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 433.27 km2 (167.29 sq mi) |

| • Land | 425.47 km2 (164.27 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 232[2] in Norway |

| Population (30 September 2020) | |

| • Total | 64,345 |

| • Rank | 11th in Norway |

| • Density | 338.8/km2 (877/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | 46% |

| Demonym(s) | Sandefjording[3] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-3804 |

| Official language form | Bokmål[4] |

| Website | www |

Sandefjord (![]() pronunciation (help·info)) is a city and the most populous municipality in Vestfold og Telemark county, Norway. The municipality of Sandefjord was established on 1 January 1838. The municipality of Sandar was merged into Sandefjord on 1 January 1969. On 1 January 2017, rural municipalities of Andebu and Stokke were merged into Sandefjord as part of a nationwide municipal reform. This merger was the first one to take place during the reform.[5]

pronunciation (help·info)) is a city and the most populous municipality in Vestfold og Telemark county, Norway. The municipality of Sandefjord was established on 1 January 1838. The municipality of Sandar was merged into Sandefjord on 1 January 1969. On 1 January 2017, rural municipalities of Andebu and Stokke were merged into Sandefjord as part of a nationwide municipal reform. This merger was the first one to take place during the reform.[5]

The city is known for its rich Viking history and the prosperous whaling industry, which made Sandefjord the richest city in Norway.[6] Today, it has built up the third-largest merchant fleet in Norway.[7] It is home to Europe's only museum dedicated to whaling, and is home to Gokstad Mound where the 9th century Gokstad Ship was discovered.

Sandefjord has numerous nicknames, including the Viking or Whaling "capital" of Norway.[8][9] The city is also known as the "whaling capital of the world."[10][11][12][13] It has also been dubbed the "Bathing City" (Badebyen), due to its many beaches and former resort spas.[14] It is still considered a resort town, due to high numbers of visitors during summer months.[15]

Sandefjord has become a transportation hub, home of Torp International Airport, one of Norway's largest airports. Daily ferry connections to Sweden are provided by Fjord Line and Color Line from the city harbor. European Route E18, one of Norway's most important roads, traverses the municipality.

Sandefjord is a stronghold for the Conservative Party;[16][17][18] the Conservative coalition received over 70 percent of votes cast in 2011. Current mayor is Bjørn Ole Gleditsch from the Conservative Party, who has been mayor since 2004.

General information[]

Etymology[]

The name Sandefjord, which dates to 1200 A.D., originates from the ancient farm name Sandar.[20] The first element is the genitive case of the name of the parish and former municipality of Sandar.[21] The name Sandar derives from the Old Norse term "sandar", which is the plural form of "sandr", translating to 'stretch of sand' (sandstrekning).[22][23]

The name Sandefjord was first mentioned in chapter 169 of Sverris saga from the year 1200. It was then referring to the fjord which is now known as Sandefjordsfjord.[24]

Coat-of-arms[]

The coat-of-arms dates from modern times, having been granted on 9 May 1914.[25] The Viking ship symbolizes the famous Gokstad ship, which was found in Sandefjord in 1880, one of the best preserved Viking ships known. The whale symbolizes that in the late 19th and early 20th century, Sandefjord was a main home port for whalers operating in the southern oceans.[26]

On 1 January 2017, Sandefjord received a new coat of arm after the merge with Andebu- and Stokke municipalities.[27] The arms has the title: Courage and Strength, and is created in black and gold. The arms was designed by Erik Raastad from Sandefjord, with minor modification by the heraldic expert Jan Eide from Oslo. The decision to get a new coat of arms was made by the merger committee in Andebu on 24 May 2016.[28]

History[]

Viking history[]

Sandefjord has been inhabited for thousands of years.[20] Excavations indicate that people have inhabited Sandefjord for around 3,000 years. Rock carvings at Haugen farm by Istrehågan in Jåberg are dated to 1,500–500 BCE.[29] Haugen farm is home to Vestfold County's largest petroglyph site.[30] In 1961-1962, 78 rock carvings were discovered at the site. They consist of ships, spiral figures, circular hollows, and much more.[31]

The Vikings lived in Sandefjord and surrounding areas about 1,000 years ago, and numerous Viking artifacts and monuments can be found in Sandefjord.[32] One of the most important remains from the Viking Age was found at the grave site Gokstadhaugen (Gokstad Mound) in Sandefjord. The Gokstad ship was excavated by Nicolay Nicolaysen and is now in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo. The Viking, an exact replica of the Gokstad ship, crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Bergen to be exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. A replica of the Gokstad ship, called Gaia, currently has Sandefjord as home port.[33][29] Other known replicas include the Munin, (a half scale replica) located in Vancouver, Canada.

The Gokstad Ship, Norway's largest preserved Viking ship, was discovered during an excavation at Gokstad Mound in 1880. The Vikings first settled here due to its speedy route from Sandefjord and along the coast.[34] Viking settlements and grave sites have been discovered in Sandefjord.[35]

Sandefjord functioned as a seaport defined by the twin industries of shipping and shipbuilding throughout the 1600s and 1700s. It was formally recognized as a market town by King Oscar in 1845. Its population at the time was 749 residents.[34]

Health resort[]

The city became known as a world-renowned health resort destination between 1837 and 1939. Royalty and Prime Ministers from throughout Europe visited the town for its spas in the late 1800s.[38] The city gained its reputation as a health- and pleasure community when Sandefjord sulfur spa and resort ("Sandefjord Kurbad") was established in 1837. It was the first spa in town and functioned as a medical institution focusing on the treatment of symptoms for rheumatic diseases. The original bathhouse has been restored and is now a culture house by the city center.[34] It was one of Europe's most visited baths until its closure in 1939.[39]

Around 50,000 people, mostly Norwegians, visited the bath from 1837 to 1939. Majority of spa visitors were from Norway, but international guests from Germany, Britain and the United States also visited the spas of Sandefjord.[29] Today the bath's building, Kurbadet, has been restored and hosts cultural events and various annual activities.[40]

Town fires[]

Sandefjord has experienced numerous town fires, including a town fire in 1800 which led to most of the town burning down and subsequently having to be rebuilt.[41] An additional fire in 1900 destroyed 56 houses and caused major damage.[29] Sandefjord's most important capital, its ships, and the shipping industry, remained untouched from the major fire of March 1900.[42] The fire, which started on the night before March 16, 1900, led to the entire city center burning down, including important business offices. Both newspapers in town, Sandefjords Blad and Vestfold, saw their offices burnt down. Six jewelry stores, three watchmakers, eight grocery stores, and a variety of other shops were destroyed. The fire started in the factory Nordmannen. The fire caused the loss of 51 buildings for a total value of NOK 1.5 million in addition to NOK 1 million in loss of store items.[43] Sandefjord Church from 1872 also burnt down during the town fire of 1900.[44]

A new town fire March 27 and 28 in 1915 led to the death of two people and destroyed seven farms. Large parts of the street Storgata were also destroyed.[45][46]

Whaling and ships[]

Sandefjord is perhaps best known as a whaling community.[49] The centre of the world's modern whaling industry was located in town, and Sandefjordians not only made up practically all the crew on the Norwegian whaling fleet, but substantial numbers of Sandefjordians also worked within the whaling industry in nearby countries. For over fifty years in the late 1800s, Sandefjord functioned as the world center for the whaling industry, including the manufacture and equipment of whaling vessels, floating factories, and whale-catchers.[50] The city has also been named the "whaling capital of the world."[10][11][12][13] 25 whaling companies were established in Sandefjord between 1905 and 1914.[51] During the 1911/12 season, Sandefjord had 27 whaling companies with a total of 115 vessels. This made up over 30 percent of the world's whaling firms.[52]

From 1850, a number of ships from Sandefjord were whaling and sealing in the Arctic Ocean and along the coast of Finnmark. The first whaling expedition from Sandefjord to the Antarctic Ocean was sent in 1905. Towards the end of the 1920s, Sandefjord had a fleet of 15 factory ships and more than 90 whalers. In 1954, more than 2,800 men from the district were hired as crew on the whalers, but from the mid-1950s whaling was gradually reduced. The number of southbound expeditions rapidly decreased during the 1960s, and the 1967/68 season became the last for Sandefjord.[51] In 1971, the city’s last whale processing vessel was sold to Japan.[53] The shipping industry was gradually readjusted from whaling to other ship types during this period. The local Framnæs Mekaniske Værksted and Jotun Group Private Ltd. had major roles in this business.

Today, the memories of this important period of the city's history are kept alive at the Whaling Museum (Hvalfangstmuseet). This museum is the only museum in Europe specializing in whales and the history of whaling.[32][54] The history of the whalers can also be explored at the Museum's Wharf with a visit aboard the whale-catcher Southern Actor. Whaling is considered to be the industry which made Sandefjord the richest city in Norway.[6]

Sandefjord also has shipping traditions of tall sailing ships and steam ships. The full-rigged sailing ship Christian Radich, three-masted barquentine Endurance, whale catcher Jason and Viking ship replica Viking were some of the many ships built by Framnæs Mekaniske Værksted.

of Sandefjord established the first whaling station in the Faroe Islands in 1894, which was located at Gjánoyri on the island of Streymoy.[55][56] As of 1903, half of all whaling companies in the Faroe Islands were operated out of Sandefjord.[57] Furthermore, Sandefjord was the headquarters of the (SAWC), which was established in 1908 and managed by shipowner Johan Bryde of Sandefjord.[58] Sandefjordian whaling firms were also established on the coast of Africa, in Portugal, Mexico, Western Australia, among other places.[59]

Antarctic expeditions[]

Towards the beginning of World War I, Norwegian whaling spread throughout the world, most and foremost from Sandefjord. Expeditions from Sandefjord went as far as Norwegian Bay in Australia, Stewart Island in New Zealand, Walvis Bay in Namibia, Corral, Chile, and also isolated places such as Kerguelen Islands, South Georgia Island, Bouvet Island, and the Southern Ocean.[61]

In the 1910s, affluent Sandefjordian was given a grant to practice whaling outside Peru and Ecuador. He was also appointed Ecuador's consul to Norway. He achieved an agreement with Ecuadorian government officials which allowed Norwegians to inhabit the Galápagos Islands, and also receive 200 hectares of land, pay no taxes for ten years, and be allowed to keep their Norwegian citizenship.[62][63] Christensen created huge local interest of Galápagos, and the local company was established on 21 March 1925. Its main goal was to exploit the Norwegian fishing rights at the Galápagos Islands. A ship named Floreana departed from Sandefjord on 15 May 1925, equipped with enough men and goods to establish a colony.[64]

On 16 November 1904, Carl Anton Larsen of Sandefjord established the whaling community of Grytviken, the largest settlement in South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.[65][66] South Georgia Island lies a few thousand kilometers east of Cape Horn.[67]

Nils Larsen (1900–76) was a sea captain from Sandefjord, famous for his expeditions of Antarctica in the early 20th century. It was under his expeditions that Norway achieved annexation of Bouvet Island in 1927 and Peter I Island two years after. A cove on Antarctica's Peter I Island is named Sandefjord Cove in honor of Larsen's hometown.[68][69] Sandefjord Ice Bay in continental Antarctica is also named after Sandefjord.[70] Mount Nils Larsen in Queen Maud Land, Mount Nils in Enderby Land and Nils Larsen Glacier are examples of many geographical names given in honor of Nils Larsen.[71]

World War II[]

A week after Operation Weserübung, German forces entered Sandefjord on April 16, 1940. 30-40 men arrived in semi-trucks from Horten under the leadership of Erik von Drydalski. After handing their directives to Sandefjord police chief Kjartan Bruun Hansen, the men left for Hotel Atlantic, where they established their headquarters in the city. German troops in the city soon rose to 200.[72] At the beginning of the German occupation of Norway, a German Hafenkapitän (harbormaster) was placed at Tollboden, and a representative for was placed in an office building at Framnes verft. German soldiers could be seen marching throughout the city. At the beginning of the occupation, over 2,000 German officers visited Socitetsbygningen (today's Park Hotel), which belonged to Sandefjord Spa. The Nazi flag was waving over the building during the visit. Norwegian students were told to learn the German language, and handed out a book, . They were also given a copy of Adolf Hitler's book Mein Kampf translated into the Norwegian language.[73]

German forces constructed two coastal forts in Sandefjord, located at the southern tips of both West- and East Islands. The largest German construction in Sandefjord took place at Folehavna, where a fortress was erected in the spring of 1941. Four cannons with a target range of 14 kilometers were installed at the site, along with a 120-meter tunnel. The four 15 cm cannons were installed in concrete gun pits on the sloping rocks. German construction also took place by Goksjø Lake, and also at Jernbaneallén, where a former garage structure was turned into a prison camp.[74][75]

Many Sandefjordians were killed during World War II, including a number of seamen. Håkon Andersen of Framnes was killed onboard Arcturus when the ship was attacked by British Beaufighters. Albert K. J. Skålsvik (1921–1944) of Krokemoa, a member of the Norwegian Homefleet ("Hjemmeflåten"), was 18 years when the war broke out. Skålsvik was killed, along with the captain, when the ship DS Kong Bjørn was attacked by allied warplanes by Ryvingen Lighthouse in 1944. He is now commemorated at the Hall of Remembrance in Stavern (Larvik). Skålsvik's younger brother, Bernard, was also a part of the Homefleet and was killed at age 17 in 1945.[76][77]

Radios were illegal, and Sandefjordians such as Henry Melby of Gokstad was arrested for having a radio in 1942. He was incarcerated at the tanker Inger Johanne, which was attacked by allied warplanes in 1944, killing 15 people, including Henry Melby.[76]

In the fall of 1941, German occupation forces replaced Sandefjord's city manager Finn Sandberg with NS-member who was soon appointed mayor. Sandar received its NS mayor in November 1941, Ole Kristian Holtan.[78] Olaf Bøe from Nasjonal Samling was appointed editor for Sandefjords Presse by Anders Beggerud in 1944.[79]

Following World War II, Norway became one of the founding members of NATO and several air bases were constructed in Norway using NATO funds. One of these was Sandefjord Airport Torp, which was to be used by the United States Air Force in case of war. Construction began in 1953 and was completed in July 1956.

SAS merge[]

The municipalities of Sandefjord (S), Andebu (A) and Stokke (S) merged on 1 January 2017. The merge was the first of numerous nationwide merges following a municipal reform by the Solberg Cabinet.[80][81] The "new" municipality is 425.47 km2, including freshwater lakes and rivers.[82] It is 11th most populated municipality in Norway, and the most populous in Vestfold County.[2] Proposed names for the "new" municipality were Gokstad, Sandar and Torp, however, the name Sandefjord was ultimately kept.[83]

A poll conducted by Sandefjords blad in January 2015 called 600 residents in Andebu, 750 in Stokke, and 1,000 in Sandefjord. All were given the question "Do you think Stokke, Andebu, and Sandefjord should establish one single municipality?". 69% of Sandefjord residents answered "yes", while 64% (Andebu) and 61% (Stokke) answered "yes" in Stokke and Andebu.[84]

Few Stokke residents read Sandefjords Blad, the main newspaper of Sandefjord, and relatively few residents commute to Sandefjord proper for work. However, Sandefjord's wealth and its international airport have been seen as key factors as to why Stokke residents decided to merge.[85] 77.8 percent of Stokke residents ultimately voted to merge into Sandefjord during the September 2015 elections.[86]

Historical population[]

The city experienced a 98.6 percent population growth from 1875 to 1900. Even not including Sandar's merge into Sandefjord in 1888, this population increase was substantially higher than most Norwegian cities. Sandar experienced the largest population growth of any Norwegian town, and over twice the growth of other towns in Vestfold County.[87]

From 1875 to 1900, the disposable income of Sandefjordians increased by over 200 percent.[88] Total assets in local banks also increased, and in 1895–1900, total assets went from 0.6 to 1.9 million in Aktiekreditbanken and from 1.1 million to 1.3 million in Sandefjords Sparebank.[89] Even after whaling lost its importance, Sandefjord remained Norway's richest city, and from 1913 to 1917, the median income increased by over 350 percent.[90]

| Year | Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 373[91] | |

| 1825 | 590[92] | |

| 1845 | 749 | |

| 1865 | 1,796[91] | |

| 1875 | 2,484[91] | |

| 1900 | 5,180[91] | |

| 1951 | 6,717[93] | |

| 1960 | 6,696 | |

| 1970 | 31,752 | Sandefjord and Sandar merged on 1 January 1969[25] |

| 1980 | 34,758 | |

| 1990 | 35,888 | |

| 2000 | 39,317 | |

| 2010 | 43,126[94] | |

| 2017 | 61,218 | Sandefjord, Stokke and Andebu merged on 1 January 2017[95] |

| 2020 | 63,764[96] |

Geography[]

Sandefjord is a coastal city on the western shore of the Oslo Fjord. It can be described as a suburb of Oslo, situated 110 kilometres (68 mi) southwest of the capital.[99] It is the largest city in Vestfold og Telemark County. Its 93-mile long coastline has various beaches and sheltered coves, and several forests are also within city limits.[32] The two peninsulas called Østerøya ("East Island") and Vesterøya ("West Island") contribute to a total coastline of 146 kilometres (91 mi), and form the Sandefjordsfjord and Mefjord. The coastline offers a wide variety of sandy beaches, skerries, and islets (116 in total), along with bays and sloping rocks. Forested areas are often laced with paths and lighted for trails for summer hikes and winter skiing.[100] Of Sandefjord's total area, 37.7 square kilometres (14.6 sq mi) (31%) is agricultural and 36.2 square kilometres (14.0 sq mi) (26%) is forest. 2 percent is made up of lakes and rivers.[101] Neighbouring towns are Tønsberg and Larvik.

124[102]-116 islands are within city limits. Small island bays give shelter for overnight campers, and many islets have relatively accessible beaches.[97][103] Sandefjord is home to several peninsulas, including West Island (12 km²), East Island (8 km²), Engø (1 km²), Marøy, and Årø. Langøya (Langø) is the largest island at 0.55 km², while other islands include Ravnø (0.40 km²), Skogøy/Storøya (0.25 km²), (0.2 km²), Storholmen (0.13 km²), Ormestadholmen (0.1 km²), Grindholmen (0.08 km²), and Granholmen (12 acres). Despite its location in-between Flautangen and Lindholmen (Tjøme) in the Tønsbergfjord, the archipelago of Stauper belongs to Sandefjord. It consists of ten large islands and a number of smaller skerries and islets.[104]

There were two natural lakes in Sandefjord prior to the 2017 merge: Goksjø, which is the third-largest in Vestfold County, and the smaller Napperødtjern (2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft)).[105] Napperødtjern lies a few hundred meters north of Goksjø and is a nature preserve surrounded by swamp forests and wetland.[106] Artificial ponds include Bugårdsdammen, , Virikdammen, Kroksjø, Veradammen, Svarttjern, and others. Local wildlife such as moose, deer, and avifauna can often be observed near freshwater lakes and rivers.[107]

Sandefjord has four fjords: Sandefjordsfjord, Lahellefjord, Mefjord, and , which it shares with neighboring Tønsberg.[108]

The highest point in the municipality is at 398.9 metres (1,309 ft), which lies northwest of Høyjord.[109] at 148 metres (486 ft) above sea level is the highest point in the city of Sandefjord. From the peak are surrounding views of the Oslofjord, by Skien, Skrim and Torp.[110][111]

Climate[]

The climate of the entirety of Norway is extremely affected by the Gulf Stream. Were it not for the warming effects of the Gulf Stream, coastal cities by Oslo Fjord would be up to 4 °C (7 °F) colder.[112] This means that the climate, the summers especially, are warmer than in other regions at the same latitude, i.e. the State of Alaska or Siberia.[113][114] Sandefjord has a higher latitude than Juneau, Alaska; Sandefjord is at 59°08′N, while the capital of Alaska is at 58°18′N. Sandefjord experiences more sun than any other Norwegian city during the summer months.[115]

Warm breezes from Skagerrak cause a mild climate, and Sandefjord experiences the highest annual number of cloud-free days in Norway.[99] The climate is relatively mild for its latitude. Fields become green in early May, but the air remains slightly cold. The summer seldom begins before the end of May, when temperatures often rapidly increase. The whole month of June and most of July experience little darkness during night and songbirds are silent for only 2–3 hours at most.[116] July is the warmest month of the year in Sandefjord when temperatures often rise above 20 °C (68 °F).[117]

Sandefjord has a relatively humid continental climate (Dfb) with warm summers, no dry season, and relatively much precipitation year long. During the colder season, which is from the end of November until early March, there is a 56 percent average chance that precipitation will be observed during a given day. The likelihood of snow falling is highest in late January and the season in which it is likely to snowfall spans from early November until early April. The coldest day of the year in Sandefjord is 4 February, with an average low temperature of −6 °C (21 °F) and average high of only −1 °C (30 °F).[118]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

6 (43) |

11 (52) |

18 (64) |

24 (75) |

26 (79) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

22 (72) |

16 (61) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

28 (82) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1 (34) |

1 (34) |

4 (39) |

10 (50) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

22 (72) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

11 (52) |

5 (41) |

1 (34) |

11 (51) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11 (52) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−5 (23) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

5 (41) |

1 (34) |

−3 (27) |

4 (39) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −14 (7) |

−14 (7) |

−10 (14) |

−4 (25) |

1 (34) |

5 (41) |

9 (48) |

8 (46) |

2 (36) |

−2 (28) |

−6 (21) |

−11 (12) |

−14 (7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 75 (3.0) |

53 (2.1) |

52 (2.0) |

52 (2.0) |

52 (2.0) |

57 (2.2) |

60 (2.4) |

76 (3.0) |

64 (2.5) |

93 (3.7) |

83 (3.3) |

68 (2.7) |

785 (30.9) |

| Average precipitation days | 13 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 10 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 12.2 | 9.9 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 136.9 |

| Average snowy days | 6.6 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 25.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 79 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 69 | 74 | 76 | 76 | 81 | 83 | 82 | 77 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.3 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 11.3 | 12.9 | 12.2 | 10.2 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 7.4 |

| Source 1: Meteoblue[119] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: climate-data.org[120] | |||||||||||||

Villages[]

Sandefjord Municipality consists of Sandefjord proper and an additional six villages:[102]

- Stokke (2016 pop. 3,391)

- Andebu (pop. 2,160)

- Melsomvik (pop. 2,076)

- Kodal (pop. 1,002)

- (pop. 519)

- Høyjord (pop. 316)

A small part of Sandefjord – the Himberg farm – is lying as an exclave inside the borders of the municipality of Larvik.[121][122] All efforts at annexing Himberg into surrounding Larvik have been met with massive protests from local residents. A 1995 annexation attempt was ultimately canceled due to large protests from Himberg residents. Himberg is a rural agricultural community consisting of no more than ten households.[123] There are only four similar exclaves in Norway, and Himberg is the most populous exclave in the nation, with a population of around 40. It is 1.4 square kilometres (0.54 sq mi).[124]

Townscape[]

Whaler's Monument, a Sandefjord trademark, is located at the end of the city's main street, Jernbanealléen, in the harbour area.[126] Nearby are the oceanfront restaurants Kokeriet and La Scala, two of the relatively few places where whale meat is regularly served.[127][128] The Train- and nearby bus stations are approximately 800 metres (0.50 mi) up Jernbanealléen from the waterfront.[129] The main commercial areas are found on Jernbanealléen (main street), Storgata, Kongensgate and Hvaltorvet Shopping Centre.[130]

Sandefjord has a city centre, consisting of a mixture of old and modern buildings and a selection of shops.[131] It has a good selection of restaurants and cafés. According to the renowned restaurant guide, Salt & Pepper, Sandefjord holds what is possibly Norway's best gourmet restaurant which is located in a modern building near the harbour, known as Brygga11, run by Bocuse d'Or winner Geir Skeie.[132][29][133] Other restaurants include Chili, Kismat, Restaurant La Scala, Peppes Pizza, Kokeriet, Zorba, Lady og Landstryker'n, and others. Also located at the harbour, is the fishmonger well known for the quality of its goods and delicacies, including freshly caught shrimp, crab and fish.[131] The fishmonger, known as Brødrene Berggren, was established in 1911 and is among the oldest in Norway.[132][134][135][136] It processed 1,000 tons of fish and shellfish per year as of year 2000.[137]

In the Bakgaarden (backyard) area are numerous cafés, boutiques, and art shops, as well as occasional summer concerts. Restaurants are found throughout the city and offer local specialties such as smoked salmon, dry-cured salmon, moose, reindeer, grouse, and deer. Sandar Haandverksbryggeri is a popular microbrewery, while wine tastings are offered at SMAK Winebar. Bars include Draaben Bar, James Clark Pub, Brygga Bar, and Pir 4.[117]

Street names are named for notable women in the Krokemoa area, such as Lauras vei (named for Laura Konstanse Jensen in 1993[138]), planets (Mosserød), bird species (Lystad), plant species (Unneberg), rock species (Nygård), insects (Gjekstad), and Norse mythology (Breidablikk), which has streets named for Freyja, Odin, Thor, Týr, Baldr, Frigg, Mjölnir, Bragi, Urðr, Loki, Þrymr, Jötunheimr, and various Norse gods.[139][140] Streets are also named for notable people with ties to the city, including Wilhelm Wetlesen, Johan Bryde, Carl Anton Larsen, Christen Christensen, Jørgen Tandberg Ebbesen, Heinrich Arnold Thaulow, Nils Vibe Stockfleth, Peter Hersleb Harboe Castberg, Magnus Brostrup Landstad, and others.[141]

Architecture[]

Sandefjord's architecture varies from smaller tree homes to large modern complexes.[144] Sandefjord is one of few Art Nouveau towns in Norway; it is the town with the second-most Art Nouveau buildings in Norway. The major town fires of 1882, 1900 and 1915 devastated much of town and paved the way for new architecture. While neighboring towns mostly consist of wooden clapboard houses, Sandefjord is home to pastel-painted fronts, spires, turrets, and gargoyles. Jugend style structures include Saint John the Baptist's Church, Privatbanken, Gunilla's (Kongens gate 18), and an award-receiving 1915 structure at Stockfleths gate 9.[145][146] Noble examples are also found at Christopher Hvidts Plass, including the bakery Ivar Halvorsen (built in 1900) and the former Methodist Church (1918).[142][147]

Certain parts were left untouched by the town fires, including the street known as . Bjerggata is the oldest or one of the oldest parts of Sandefjord. It consists mostly of white wooden homes and is an indicator of how Sandefjord looked until the 1950s.[148][149] Most of the homes at Bjerggata are dated to the early 1800s.[150]

Other architecture includes the Viking-inspired dragon style complex from 1899, which housed Sandefjord Spa.[148][151] It is one of Scandinavia's largest wooden buildings.[36][152]

Politics and government[]

Sandefjord is a stronghold for the Conservative Party.[153] In the Norwegian local elections of 2011, 47.9% of voters voted for the Conservative Party. The right-wing parties received a total of 70.4% of the vote in Sandefjord, compared to 51.2% nationwide.[154][155][156][157][158] The current mayor, Bjørn Ole Gleditsch, was elected in 2004 with the support of the Progress Party. Gleditsch is the wealthiest mayor to ever be elected in Norway.[159][160] from the Progress Party has been deputy mayor since 2015.[161]

Municipal council[]

The municipal council of Sandefjord is made up of 57 representatives that are elected to four-year terms. Each representative from Sandefjord proper is represented by 1,160 inhabitants, representatives from Stokke by 1,045, and Andebu by 837 residents per municipal council member.[163]

The party breakdown as of 2017 is:[164]

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 15 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 6 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 1 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 23 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 4 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 2 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 57 | |

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 749 | — |

| 1951 | 6,717 | +796.8% |

| 1960 | 6,984 | +4.0% |

| 1970 | 31,752 | +354.6% |

| 1980 | 34,758 | +9.5% |

| 1990 | 35,888 | +3.3% |

| 2000 | 39,317 | +9.6% |

| 2010 | 43,126 | +9.7% |

| 2017 | 62,622 | +45.2% |

| Sandar was annexed in 1970, while Andebu and Stokke were added in 2017. Source: Statistics Norway | ||

According to Statistics Norway in 2017, the municipality is home to 62,622 residents. There were 2,797 vacation homes in Sandefjord as of 2018, and 2,19 people per housing unit. 69.2% are members of Church of Norway, 18% are unaffiliated and 12.8% are members of other religious communities.[1] In addition to State Churches, the city also houses various minor congregations, including an Adventist- and Methodist Church.[142]

Religious minorities with congregations in town include Pentecostals (Salem), Catholics (St. Johannes Døperen), Methodists (Metodistkirken), Seventh-day Adventists (Adventkirken), Baptists (Baptistkirken), Norwegian Lutheran Mission (Den lille gren), Jehovas Witnesses (Rikets Sal) and Muslims (Alkawther Islam Center and Sandefjord Islamic Center).[165] Baptists first established a congregation in town in the 1880s and Methodists in the 1890s.[166]

Brunstad Christian Church (Smith's Friends) is an evangelical non-denominational church which was established in neighboring Horten in 1905. Brunstad Conference Center is the denomination's headquarters and is located in Stokke. It is the only worldwide denomination which was established in Norway.[167][168]

The largest minority groups in 2017 (first- and second generation immigrants) are Lithuanians (1.95%), Polish (1.93%), Iraqis (1.24%), Vietnamese (0.80%), Germans (0.71%), Swedes (0.69%), Kosovans (0.67%), Bosnians (0.64%), and Danes (0.51%).[169]

Sandefjord has a high population density of 339 people per square kilometre. The population density is particularly high in Sandefjord proper, and between E18 and the coast, the city has an equivalent population density to that of the Netherlands. The population increases significantly during summer months due to tourism.[170]

After the merge with Stokke and Andebu in 2017, Sandefjord has a population of over 63,000. This makes Sandefjord to the 11th most populous municipality in Norway.[2][171] It is the most populous city in Vestfold County;[172] One in four people from Vestfold County are from Sandefjord, or 25.2 percent of the county population.[173]

Economy[]

Sandefjord is the wealthiest city in Norway.[6][174] Important industries in Sandefjord are information technology, chemical production, tourism, navigation, ship building and fishing.[116][175] It is home to the international airport Torp Airport, paint producer Jotun, the brewery Grans Bryggeri, the chocolate factory Hval Sjokoladefabrikk, and the engineering company Ramboll Oil & Gas. High-tech and information technology have become important industries in recent times,[176] represented by some of Norway's largest web shops: Komplett, mpx.no, and netshop.no.

The largest employer, besides the city itself, is Jotun, which was established in Sandefjord in 1926. Jotun is now one of the world's largest manufacturers of paints and coating products.[177][178] As of February 2017, Jotun has a presence in over 100 countries and employed 9,500 employees worldwide. The Jotun Group operates four divisions, while its head office is located in Sandefjord.[29] As of 2016, Jotun had 9,800 employees including one thousand employees within Norway. It operated 37 factories in 21 countries and is represented in 120 countries through distributors, offices, and agents. It is owned by the Gleditsch family and Orkla ASA.[179]

While Jotun by far is the largest company in Vestfold County, the second-biggest company is Komplett. A web shop operating in all of Scandinavia, Komplett had a 7.3 billion NOK revenue in 2015 and had 800 employees.[180]

Sandefjord had Norway's most expensive seaside vacation homes as of 2011, with an average price of 7.2 million crowns.[181] General property values in Sandefjord appreciated 25.7 percent between 2010 and 2015.[182]

Largest companies in Sandefjord based on operating income in 2015:[185]

| No. | Company name | Operating income in 2015 (in NOK) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jotun | 16,844,327,000 |

| 2 | Komplett | 7,256,700,000 |

| 3 | Skjeggerød AS | 4,523,277,000 |

| 4 | ALSO AS | 2,457,643,000 |

| 5 | Carlsen Fritzøe AS | 1,543,189,000 |

Tourism[]

Sandefjord is dubbed a resort town due to its many summer visitors.[15] Sandefjord is also nicknamed the "Bathing City" due to its many beaches, islands and minor archipelagos. Beaches such as Vøra and nearby Langeby on West Island attract summer visitors from Oslo and other larger Norwegian cities.[14] Sandefjord became a bathing destination when sulphur was discovered in waters and gyttja in 1837.[172][186]

Sandefjord is home to over two thousand vacation homes, most of which are built along the seaside.[102] Sandefjord had Norway's most expensive vacation homes as of 2012; the mean vacation home price was 7.1 million crowns in 2012.[187]

The city of Sandefjord may be best known for its bathing and many beaches.[190][191] It is first and foremost known as a summer community.[99][192][193] The city lies on a low, slightly inclined strand, protected on three sides by hills, and only open towards the south where the Sandefjordsfjord is located. It is known for its great bathing and pure sea water quality. It has a country-like appearance with clean streets and quaint roads. The city is dependent on the bathing establishment during the summer season when many tourists arrive in Sandefjord.[116] The bathing season in Sandefjord generally begins on 1 June, while it ends on the last day of August.[194]

Visitors to Sandefjord Spa in the 19th century were the city's first tourists, and made Sandefjord into a popular holiday destination.[195] The city's fame as a seaside mecca dates back to 1837, when sulphur springs first were discovered in town.[151] Sandefjord has been nicknamed "Eastern Norway's vacation paradise." A majority of current tourists and vacation homeowners are from the capital of Oslo.[99]

Sandefjord is home to four hotels: Scandic Park Hotel, , Torp Hotel, and Clarion Collection Hotel Atlantic.[196][197]

Culture[]

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| 1,121 | |

| 1,111 | |

| 733 | |

| 504 | |

| 429 | |

| 423 | |

| 408 | |

| 394 | |

| 319 | |

| 298 | |

| 250 | |

| 207 | |

| 191 | |

| 189 | |

| 182 |

The 9th century Gokstad Ship was discovered in Sandefjord during an 1880 excavation led by Nicolay Nicolaysen. The ship itself, which is now at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, was built around year 910. It is the largest preserved Viking ship in Norway.[51][199][200] A Viking chieftain was buried at the Gokstad Mound (Gokstadhaugen), along with the 23.5-meter Gokstad Ship. Interpretive signs have been put up at the Gokstad Mound on Helgerødveien.[201][202]

Sandefjord has four churches remaining from the Middle Ages: Høyjord Stave Church, Kodal Church, Skjee Church, and Andebu Church. While Andebu Church has Norway's oldest parish register (dated 1623), Høyjord stave church is the only stave church left in Vestfold County. Its chancel dates to the year 1100 and is the oldest part of the church. Burial mounds dating to the Viking Age can be seen around the church.[102][203] Sandar Church by Sandefjord Station was constructed atop of the ruins of a Medieval church dated to the 13th century. The present church, however, was erected in 1792.[204][205][206]

Midtåsen Sculpture Park contains a collection of bronze- and marbleworks by sculptor Knut Steen, which is housed in a pine forest pavilion overlooking Sandefjord and its fjord.[207] The former estate of shipping magnate Anders Jahre is located at Midtåsen, and is now owned by the municipality. Guided tours of the villa are available.[208] The 1200 km2 (23,916 sq. ft.) villa was designed by architect Arnstein Arneberg. It is located in a 60-decare (15 acre) park.[209]

Hjertnes Civic and Theater Center is home to three auditoriums and an outdoor amphitheater. A movie theater, City Hall and library are found at Hjertnes. Concerts, opera, and other cultural events also take place at Hjertnes Civic Center.[210]

Art[]

Sandefjord is the city in Norway with the most sculptures per inhabitant. The city is home to around 100 sculptures from over 50 artists and sculptors including Ørnulf Bast, Nils Aas, Dagfin Werenskiold, Knut Steen, Per Krogh, and others. Notable sculptures include the Whaler's Monument and the Sea Queen (“Havdronningen”) by Arnold Haukeland, which is located outside Hjertnes Civic and Theater Center.[211] contains a collection of bronze and marble works by Knut Steen in a park and villa designed by Arnstein Arneberg. Poseidon Sculpture Park, which is located in Badeparken, features Greek mythology sculptures by Nina Sundbye. Arne Durban’s sculpture "Mother and Child" is located in the City Park (“Byparken”), while a sculpture of priest Magnus Brostrup Landstad made by Hans Holmen can be seen at Landstads plass by Sandar Church. A polar bear sculpture by Skule Waksvik is located outside Sandefjord Museum, while a whale jawbone arch is placed outside Scandic Park Hotel. A memorial to fallen sailors (Sjømannsminnesmerket) was placed outside Sandefjord Church in 1920 and was made by sculptor Gustav Lærum.[212]

The fountain at Christopher Hvidts Plass, the Thaulow fountain, was donated to the city in 1875 by Heinrich Arnold Thaulow, the city's first physician and founder of Sandefjord Spa. It is the city's oldest sculpture and its first donation.[213]

In 2017, the NGO Art for All in the World conducted a project where seven mural artists contributed. A mural by Eduardo Kobra, “Peace between nations”, can be seen behind Peter Grøns gate 2B. Street art by graffiti artist Victor Ash can be seen at Stockfeldsgate 6-8.[214]

Museums[]

Sandefjord is home to Europe's only museum dedicated to whaling, which is located in the city center.[32][215] The museum was one of the first original museums in Norway when established in 1917. Today it boasts over 150,000 photographs as well as exhibits of marine animals, a restored whale catcher, and more.[54][216] A whale catcher named Southern Actor is docked at Museum's Wharf and is a part of the Maritime Museum. It is the only whale catcher from the Modern Whaling Epoch still to be in its original working order. It was constructed by in 1950 and brought to Sandefjord in 1989.[217][218] Museum's Wharf ("Museumsbrygga") was established in 1995 and both the Gaia ship and Southern Actor were placed at the wharf.[219]

There are six protected buildings in Sandefjord as of 2008: City Museum (Bymuseet), Maritime Museum (Sjøfartsmuséet), and the three farms Elverhøy-, Nordby-, and Auve farms. The city's oldest house, which is located at Skippergaten 6 and was built in 1667, is also one of the city's protected structures.[220] The City Museum and Maritime Museum, along with Sandefjord Museum, are the three museums found in Sandefjord. Sandefjord Museum is among the world's largest whaling museums.[183][221] It was established in 1917 and was a gift to the city from Lars Christensen.[222]

Transportation[]

Sandefjord Airport Torp is one of Norway's largest airports, and is particularly known for its high number of international flights.[225][226] Torp is Norway's second-largest airport in terms of international flights in 2003. As of 2003, Torp had over one million annual passengers, of which around 50% were for international flights.[227] Despite being located 74 miles south of Oslo, Torp is sometimes called Oslo Airport Torp. It is reached with a free shuttle bus from Sandefjord Airport Station on Vestfoldbanen.

Sandefjord Airport is a budget airline hub for airlines such as Widerøe, Ryanair, and Wizz Air.[228] Torp offers direct routes to over 30 international and domestic destinations,[229] including daily flights to European cities such as London and Amsterdam.[177] The city is served by frequent intercity trains to Oslo and onwards to Oslo Airport.

Daily ferries connect Sandefjord to Sweden.[29][230] Color Line ferries MS Color Hybrid and Color Viking connect the town to Strömstad in Sweden.[230] Fjord Line is another ferry service connecting Sandefjord and Sweden.[231] Neighboring town of Larvik is home to daily ferry operations between Norway and Hirtshals, Denmark.[232] was a former ferry service operating ferries between Sandefjord and Sweden.[233][234] Sandefjord is also home to a domestic ferry route: MF Jutøya transports people and goods to Veierland Island from Engø peninsula several times per day.[235][236] Sandefjord is also a cruise ship destination.[130][237]

European route E18 traverses the municipality. It is one of Norway's most important main roads, and makes the drive to Oslo approximately 90 minutes.[195]

Public transit[]

Sandefjord Station is the central train station and is served by regional trains operated by Vy. The main bus station is also located by Sandefjord Station. Fast and frequent express buses from Sandefjord shuttle along E18, connecting to Kristiansand and linking key resorts in Southern Norway.[129] Trains and buses for Sandefjord leave Oslo Central Station (Oslo S) every 30 minutes, and the journey takes two hours.[239] The public transportation system in Sandefjord is known as Vestfold Kollektivtrafikk (VKT).[240]

Besides Sandefjord Station, additional railway stations include Sandefjord Airport Station and Stokke Station. Torp Express Bus Service operates buses from Sandefjord Airport to Oslo. There are free shuttle buses between Sandefjord Airport Station and Sandefjord Airport.[241]

Sports[]

Bugårds Park is home to the city's largest sporting grounds and facilities, including areas for soccer, tennis, handball, badminton, archery, rollerskating, horseback-riding, water sports, ice hockey, and ice skating. The 60-acre park sits by Sandefjord High School and is also home to a walking path, duck pond and designated picnic areas. The swimming center with its 2,500 m2 public pool is also located in Bugårds Park. Indoor handball courts are housed in Jotunhallen, while tennis courts are found in Pingvinhallen.[210][242]

Sandefjord Golfbane is an 18-hole golf course located at Jåberg, 5 km (3.1 mi.) from the city center. It was designed by Peter Chamberlin. It was established in August 2009.[243][244]

Professional sports[]

Sandefjord Fotball is a professional football club which plays in Tippeligaen/Eliteserien (Norwegian Premier League). The team previously played home games at Storstadion, but has played at Komplett Arena since its opening in 2007. The club reached the Norwegian First Division in 1999, the year after its foundation.

Sandefjord is noted for its strong performance in professional handball. The city is home to two top league handball teams: Sandefjord TIF and IL Runar.[245] From 1991 to 2008 Sandefjord TIF won nine Men's Premier League and another local team, Runar Håndball, won four.[246] Sandefjord TIF Handball won the Men's Premier League again in 2005–06.

In professional ice skating, Sandefjord has been the location of Norwegian Allround Championships in 1928, 1958, and 1961.[247]

Education[]

Sandefjord High School (SVGS) has about 2,000 students and is Norway's largest high school.[248][249] It is a result of the merge between Sandefjord's four former high schools.[250] Skagerak International School is also located in town and offers English-speaking kindergarten, elementary school, middle school, and high school. Other private schools include Moe- and Mokollen schools. Skiringssal folkehøyskole is a folk high school in Sandefjord, which is owned by Vestfold County.[172] There are six public middle schools in Sandefjord: Andebu-, Breidablikk-, Bugården-, Ranvik-, Stokke- and Varden middle schools. There are 21 public elementary schools in town.[251]

Sandefjord High School (SVGS) and its two-story 32,000 m2 (344,000 sq. ft.) facilities are located at Krokemoa near the Bugårds Park. It is a public International Baccalaureate World School,[252][253] but also offers general academics (the college preparatory studiespesialisering of the Norwegian school system), as well as elite sports, vocational education, and more.[248][249]

Skagerak International School is a private, English-language, International Baccalaureate World School at Framnes.[254][255] Its education is offered to both international- and Norwegian students. Established as a High School in 1991, the school expanded to include a kindergarten as well as Primary- and Middle schools in 2000. The basis of the education is formed by the International Baccalaureate Primary Years (PYP), Middle Years (MYP) and Diploma (DP) programs. Skagerak is located in a renovated shipyard on the waterfront at Framnes. Camps and excursions are offered for all Primary- and Middle School students, as well as two or more annual trips abroad. High School students travel abroad for cultural and service-oriented trips, mostly to areas in Europe, Central Asia, and Africa. The High School is a member of UNESCO's SOUL project.[256][257]

As of 2018, 250 students are enrolled at at Torp Airport.[258]

Points of interest[]

Notable points of interest include:[29][261]

- Gokstad Burial Mound, site of the discovery of the 9th-century Gokstad Ship.

- Sandefjord Museum (the Whaling Museum), Europe's only museum dedicated to the whaling industry.[215][264][265]

- Southern Actor, whale-catcher turned museum ship. Only whale catcher from the Modern Whaling Epoch still to be in its original working order.[172][266][267]

- Whaler's Monument, rotating bronze monument, erected in honor of pioneering whalers

- Sandefjord Spa (Kurbadet), the 1899 thermal baths are housed in one of Scandinavia's largest wooden buildings.

- Bjerggata, one of the oldest parts of town with preserved wooden houses.[149][268]

- Hjertnes Civic and Theater Center, adjacent to Badeparken and Scandic Park Hotel.

- Sandar Church, built on ruins of a 13th-century medieval stone church. Present church was erected in 1792.[269]

- Gaia ship, 1990 replica of the Gokstad Ship at Museum's Wharf in Sandefjord Harbor.

- , 1903 church, home of Sandefjord Church Bells and host of various concerts and events.

- Høyjord Stave Church, in Andebu, only preserved stave church in Vestfold County.[270][271]

- Hvaltorvet Shopping Centre, largest shopping mall in Sandefjord, located in the city center.[272]

- Harbour Chapel ("Bryggekapellet"), Europe's only floating church.[273]

- Folehavna Fort, ruins from a German fortress constructed in 1941 during the German occupation of Norway.[274][275]

- Sundås Fort, ruins from fortifications constructed in 1899 during the Union between Sweden and Norway.[276][277]

- Istrehågan, ancient burial ground which dates to the Roman Iron Age around 1500–500 BCE.[278]

- Dakota Norway, Norway's only Douglas DC-3 aircraft is based at Torp.[279][280][281]

Recreation[]

Sandefjord has some of Eastern Norway's largest preserved coastal recreation areas.[283][195] This includes Yxnøy, which is one of the largest preserved nature areas along Vestfold's coast.[284] There are 20 km (12.4 mi) of coastal hiking trails on Østerøya peninsula, including to its southern tip where Tønsberg Barrel is located. Tønsberg Barrel is an old beacon mentioned in Sverris saga. The 20 km coastal path at Østerøya (East Island) is an extension of the 25 km (15.5 mi) coastal path on Vesterøya (West Island).[285] These 45 kilometers (28 mi.) of hiking trails are part of the international North Sea Trail.[286][287] Additional hiking trails are found at Preståsen, Hjertnes Forest, Fjellvikåsen, Mokollen, Midtås, as well as the Culture Walk.[288] 100 km of hiking trails are attached to trailheads by Heisetra in rural Andebu.[289][290][291] Sandefjord is home to ten cross-country skiing trails (loipes).[292]

Goksjø is a 3.47 km2 (2.15 mi2) lake on the border between Sandefjord, Larvik, and Andebu. It is the third-largest lake in Vestfold County.[293] Goksjø is popular for swimming, kayaking and fishing; some of the fish species found here are Northern pike, European perch, Ide, Common dace, European eel, Salmon and Brown trout.[294] Freshwater fishing is also common by rivers such as Svartåa in Andebu and the Hagenes River in Kodal. Numedalslågen, which is considered one of Norway's best salmon fishing rivers, is located in neighboring town of Larvik.[175][295][296]

Sandefjord is home to numerous campgrounds, all which are located along the seaside. Campgrounds include Asnes, Langeby, Vøra, Sjøbakken, Strand Leirsted, Solløkka, and islands such as Granholmen and Natholmen.[297][195][298] Langeby is considered Sandefjord's best beach by Frommer's[299] and Fodor's Travel Guides,[191] and is home to Langeby Camping which offers boat- and kayak rentals. Tent camping is permitted on numerous nearby islands, including the 11-acre (4.5 ha) Hellesøya[300] and 12-acre (5 ha) Buerøya.[301][302] Langeby lies adjacent to , a neighboring beach and campground. Vøra tends to get crowded during warm summer days due to tourism. It attracts summer vacationers from throughout Norway during warm summer months.[188][189]

The archipelago of Stauper in the Tønsbergfjord, in-between Tjøme and Østerøya, is particularly popular during summer months. These islands are popular for swimming, kayaking, boating, and camping. It consists of four larger islands, four small islands, and a number of islets.[303][304]

Tent camping is permitted in forests, minimum 150 meters (492 ft.) from nearest settlement.[305][306]

Beaches[]

Sandefjord's 146 km (90.7 mi.) of coastline is home to various beaches:[307][308][309]

- Asnes (West Island): Campground, convenience store, public restrooms, diving boards, sloping rocks.

- Flautangen (East Island): Firepits, fishing, public restrooms.

- Folehavna (West Island): Hiking trails, fishing, sloping rocks. Ruins from a German fortress built in 1941.[310][311]

- Fruvika (West Island): Firepits, benches, public restrooms.

- Granholmen (islet): Campground, convenience store, public restrooms, pier, boat rentals, playground.

- Grubesand (West Island): 100-meter beach with hiking trails, firepits, sloping rocks, picnic tables, fishing, and public restrooms.

- Langeby (West Island): Campground, convenience store, fishing, boat pier, restrooms, sloping rocks, floating platform, diving boards, showers, volleyball court, soccer field, playground.

- Sandtangen (Goksjø Lake): Freshwater beach with pier and floating platform.

- Skjellvika (East Island): Oceanside pier, diving boards, hiking trails, floating platform, sloping rocks.

- Strømbadet (city center): floating jetty for swimming in the Sandefjord Harbor. Access from Hjertnesstranda.

- Tangen (West Island): Diving boards, floating platform, soccer field, playground, volleyball court, benches, toilets.

- Truber and Yxnøy (East Island): Sloping rocks, public restrooms, hiking trails, picnic tables.

- Vøra (West Island): Campground, convenience store, volleyball court, public restroom, playground, soccer field, floating platform.

Additional beaches include Bogen (Nallberg), Brunstad, Kleivern, Korsvik, Kulerødvannet, Sandbånn and Rossnesodden (Melsomvik), Storevar, Stålerødvannet, Ertsvika, Strandvika, Albertstranda, Ormestadvika, Trollsvann, and Vårnes.[313]

Several islands with beaches are only accessible by boat, including Gokstadholmen, Lindholmen, Gåsø, Furuholmen, Gåsøkalven, Ravnø, Buerøya and Hellesøya.[308][314]

The lake Goksjø is home to beaches such as Gubbetangen and Sandtangen.[315]

In the early 1940s, the city, under the leadership of mayor , acquired the beaches Asnes on Vesterøya and Skjellvika on Østerøya. Mayor Holtedahl was also instrumental in acquiring the beach in 1943.[316]

Nature preserves[]

The early 1980s saw the establishment of several nature preserves in Sandefjord, including at Fokserød, , Hemskilen, and .[317]

Sandefjord is home to 16 nature preserves as of 2017:[102][318]

- Dalaåsen (beech forest)

- Flisefyr-Hidalen (forest)

- Storås and Spirås (forest)

- Veggermyra og Nordre Skarsholttjønn (marsh)

- Langø and Bokemoa (protected landscape)

- Robergvannet (wetland)

- Melsom (plant- and wildlife preserve)

- Napperødtjern (riparian forest)

- Fokserød (beech forest)

- Holtan (plant preserve)

- Strandvika (riparian forest)

- Hemskilen (wetland)

- Vøra (geological area)

- Akersvannet (marsh)

Public parks[]

Public parks in Sandefjord include:[319]

- Bugårdsparken ("the Bugårds Park"), 60-acre park that is home to Storstadion, a 20-acre duck pond, public pools, ice-skating rink, and a sports facilities.

- Byparken ("the Town Park"), built after the town fire of 1900. Home of the statue Mother and Child by Arne Durban.[320] The decision to establish a city park was made by the city council on June 28, 1901. In 1906, enough funds had been received to secure the land. The park has a cubic stone pedestal gifted to the city in May 1995 from . On this pedestal is where the “sculpture of the month” has been placed every month since 1995.[321][322]

- Badeparken ("the bathing park"), 15-acre city park with fitness trail, an amphitheater, and playground, adjacent to Scandic Park Hotel and Hjertnes Civic and Theater Center

- Poseidon Sculpture Park, sculpture park by Nina Sundbye established in 1995

- Andebuparken, park in the center of Andebu

- Sandefjord Hundepark (Sandefjord Dog Park), dog park near Sandefjord Upper Secondary School managed by Sandefjord hundeklubb

- , 15-acre park at Anders Jahre's former villa, sculptures and views of the Sandefjordsfjord. The park was dedicated to artist Knut Steen.[323]

- Hjertnesstranda ("the Hjertnes Beach"), park at the harbor-front with barbecue grills, sand volleyball fields, benches, public toilets.

- Sandefjord Skatepark

- Kirkeparken ("the church park"), park immediately west of Sandefjord Church.[324]

- Preståsen, park and recreation area situated on a 44-meter (144 ft.) high hill overlooking the city. Preståsen has various hiking trails, benches, a playground, barbecue sites, a water fountain, and , which is a large pond. It has two access points from Bjerggata in the city center.[325][326]

Notable residents[]

Business & Public Service[]

- Christen Christensen (1845–1923) a Norwegian shipyard and ship-owner

- Johan Bryde (1858–1925) a ship owner and whaler, set up a whaling station in South Africa

- Carl Anton Larsen (1860–1924) an Antarctic explorer, set up the Antarctic whaling industry and the settlement at Grytviken on South Georgia

- Olaf Alfred Hoffstad (1865–1943) botanist, school principal and Mayor of Sandefjord, 1911/1934

- Christian Theodore Pedersen (1876–1969), Norwegian American seaman, whaling captain and fur trader in Alaska, Canada and the northern Pacific

- Lars Christensen (1884–1965) a Norwegian shipowner and whaling magnate

- Ole Aanderud Larsen (1884–1964), ship designer, co-founder of the paint company Jotun

- Ingrid Christensen (1891–1976) polar explorer, first woman to set foot on Antarctica

- Anders Jahre (1891–1982) shipping magnate

- Odd Gleditsch, Sr. (1895–1990), business entrepreneur, co-founder of the paint company Jotun

- Theodore Theodorsen (1897–1978), Norwegian American theoretical aerodynamicist

- Anton Fredrik Klaveness (1903–1981) a Norwegian equestrian and ship-owner

- Karenanne Gussgard (born 1940) retired justice of the Supreme Court of Norway 1990/2010

- Bjørn Ole Gleditsch (born 1963) heir to paint co. Jotun; Mayor of Sandefjord since 2003

- Marie Benedicte Bjørnland (born 1965) head, Norwegian Police Security Service 2012/2019

- Frederic Hauge (born 1965) environmental activist, founded and runs Bellona Foundation

The Arts[]

- Ole Windingstad (1886–1959) a Norwegian conductor, pianist and composer

- Eline Nygaard Riisnæs (1913–2011) a pianist and musicologist at UiO

- Teddy Nelson (1939–1992) country music singer, sang with Skeeter Davis

- Dag Solstad (born 1941) a Norwegian novelist, short-story writer and dramatist

- Lorene Yarnell (1944–2010) a dancer and actress, one of an American mime duo

- Karin Fossum (born 1954) a Norwegian author of crime fiction; the "Norwegian queen of crime"

- Bent Hamer (born 1956) a film director, writer and producer [327]

- Anita Hegerland (born 1961) singer [328]

- Finn Gjerdrum (born 1961) a Norwegian film producer [329]

- Petter Wettre (born 1967) a jazz musician (Saxophone) and composer

- Thomas Numme (born 1970) television host

- Espen Sandberg (born 1971) a Norwegian film director and advertising producer [330]

- Joachim Rønning (born 1972) film director [331]

- Ina Wroldsen (born 1984) a Norwegian singer and songwriter

- Per Fredrik Åsly (born 1986) known as PelleK an actor, composer, singer and YouTuber [332]

- Lukas Zabulionis (born 1992) a saxophonist and composer, lives in Sandefjord

- and Jazz musicians (and brothers)

- Nils Mathisen (born 1959) keyboards, violin, guitar and bass and composer,

- Ole Mathisen (born 1965) saxophone and clarinet and composer

- Hans Mathisen (born 1967) guitarist

- Per Mathisen (born 1969) bassist and composer

Sport[]

- Thorbjørn Svenssen (1924–2011) footballer with a then record of 104 caps for Norway

- Solfrid Johansen (born 1956) sport rower, came 4th & 5th at 1976 & 1984 Summer Olympics

- Erik Bjørkum (born 1965) a sailor and team silver medallist at the 1988 Summer Olympics

- Ronny Johnsen (born 1969), footballer with 384 club caps and 62 for Norway

- Morten Fevang (born 1975) a football midfielder with 400 club caps

- Geir Ludvig Fevang (born 1980) a retired football midfielder with 390 club caps

In popular culture[]

- Both directors of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017), Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg, are from Sandefjord.

- Hodet over vannet (1993) was filmed at Yxney on Østerøya in Sandefjord.[333][334] The 1996-remake is starring Cameron Diaz.

- (2005), Norwegian film based on the 1994 Torp hostage crisis. It was directed by Nils Gaup and written by Jo Nesbø.[335][336]

- An episode, "Power Junkies" (season 1), of Outrageous Acts of Science (2012) was partly shot in Sandefjord.[337]

- Episode #5.26 of the British TV series Coach Trip (2010) was shot in Sandefjord.[338]

- Den starkaste (1929), Swedish silent film partly shot in Sandefjord.[339]

- Valfångare (1939), Swedish movie filmed in Sandefjord.[340][341] It was directed by Anders Henrikson and Tancred Ibsen.

- Music video for "Belinda" (2021) by Marcus & Martinus was shot at Sandefjord Airport

- "Sang til Sandefjord", song played daily by Sandefjord Church

- Music video for "The Cabin" (2013) by Ylvis was shot in Andebu, Sandefjord.[342]

- Music video for "Hvalfangsmuseet" (2011) by Bare Egil Band was shot in Sandefjord.[343]

- The Machinery (2020–), Viaplay TV show featuring Kristoffer Joner . It is based in and filmed in Sandefjord. Filming began in Sandefjord in 2019.[344][345]

The city is mentioned in a number of songs, including "Ola var fra Sandefjord" (by Einar Rose, later recorded by the Johnny Band and others), "I Sandefjord by" (Anita Hegerland), "En sang om en sjømann" (Lillebjørn Nilsen) , "Oasen 2014" (Tix), "Medvind" (Erik og Kriss), "Vanvittig Utopi II" (Gatas Parlament) , "Så Det På TV" (Postgirobygget) , and "Helt om natten, helt om dagen" (Lars Vaular) .

Fauna[]

Wildlife includes the Mountain hare, European badger, European beaver, Roe deer, Red deer, Moose, Red fox, European hedgehog, European pine marten, and Norway lemming. More rare but occasionally encountered are the Gray wolf, Eurasian lynx, Wolverine and Brown bear.

Wolves are extremely rare in Sandefjord, although they have been observed on numerous occasions.[348][349] A wolf shot in neighboring Lardal in 2013 was the first wolf killed in Vestfold County in over 100 years.[350]

Common European Viper is the only venomous snake found in Norway.[351] There are an additional two non-venomous snake species found in Vestfold County: European grass snake and European smooth snake. The Slowworm is considered a lizard.[352]

Gallery[]

17 May parade, 2016

Tønsberg Barrel at the southern tip of Østerøya

Sandefjord in 1848, painting

Sandefjord Church

Seaside entry to Sandefjord

Typical house in Bjerggata

Sandefjord, spring 2019

Clarion Collection Hotel Atlantic

Sandefjord High School is Norway's largest.

City Park (Byparken)

See also[]

- List of schools in Sandefjord

- Sandefjords Blad (local newspaper)

- Larvik and Sandefjord metropolitan region

- Sang til Sandefjord

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kommunefakta Sandefjord". ssb.no.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én. Erlend Larsen Forlag. pp. 13 and 171. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Porter, Darwin and Danforth Prince (2003). Frommer's Norway. Wiley. p. 158. ISBN 9780764524677.

- ^ "Things to Do in Sandefjord – Frommer's". Frommers.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Three shot in Sandefjord". Newsinenglish.no. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "The Viking trail through Vestfold, Norway" (PDF). Destinationviking.no. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Engel, Lyle Kenyon (1963). Scandinavia: A Simon & Schuster Travel Guide. Cornerstone Library. p. 145.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ryder, Simon and Cameron Duffy (2018). Insight Guides Norway. Insight Guides. p. 163. ISBN 978-1786717580.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alspaugh, Emmanuelle (2006). Fodor's Norway. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 73. ISBN 9781400016143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1985). Sandefjord: A modern city with vast potential. Grafisk Studio. p. 81. ISBN 82-90636-00-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alspaugh, Emmanuelle (2006). Fodor's Norway. Fodor's Travel Publications. pp. F-7, 73. ISBN 9781400016143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berman, Martha (1995). Fielding's Scandinavia. Fielding Worldwide. p. 240. ISBN 9781569520499.

- ^ "Høyre vant valget i Sandefjord". Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 September 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Mørkeblått flertall i 61 kommuner". Kommunal-rapport.no. 11 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Karakterer". Klassekampen. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1998). Bli kjent med Vestfold / Become acquainted with Vestfold. Stavanger Offset AS. p. 96. ISBN 9788290636017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tore, Sandberg and Cato Arveschoug (2001). Sandefjord zoomet inn av fotograf Tore Sandberg. C. Arveschoug and Magne Helland. p. 6. ISBN 9788299616706.

- ^ Rygh, Oluf (1907). Norske gaardnavne: Jarlsberg og Larviks amt (in Norwegian) (6 ed.). Kristiania, Norge: W. C. Fabritius & sønners bogtrikkeri. p. 260.

- ^ Thorsnæs, Geir (8 June 2017). "Sandar – tidligere kommune". Great Norwegian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Aadnevik, Kjell-Einar (2019). Turguide til Larvik og Omegn. Dreyers forlag. Page 135. ISBN 9788282654418.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. p. 353. ISBN 978-82-994567-5-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. p. 296. ISBN 978-82-994567-5-3.

- ^ Norske Kommunevåpen (1990). "Nye kommunevåbener i Norden". Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "Nytt kommunevåpen for nye Sandefjord kommune". Regjeringen.no (in Norwegian). 9 September 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ "Sandefjord kommune – Her er vårt nye kommunevåpen". Sandefjord.kommune.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Sandefjord". Gonorway.no. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Børresen, Svein E. (2004). Vestfoldboka: en reise i kultur og natur. Skagerrak forl. p. 38. ISBN 9788292284070.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (2000). Sandefjord i bilder / Sandefjord in pictures. Grafisk studio forl. Page 88. ISBN 8290636024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Sandefjord – In the footsteps of the Vikings". Visitnorway.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Gjerseth, Simen (2016). Nye Sandefjord. Liv forlag. Page 277. ISBN 9788283301137.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Local history and heritage". Sandefjord.no. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Fodor, Eugene (2004). Fodor's Scandinavia. D. McKay. p. 397. ISBN 9781400013401.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kurbadet 1837–1939". visitnorway.no.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ George, Francis Stevens (2017). Camp NoE. Lulu Publications, Inc. p. 50. ISBN 9781387047680.

- ^ Jøranlid, Marianne (1996). 40 trivelige turer i Sandefjord og omegn. Vett Viten. p. 36. ISBN 9788241202841.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2016). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Norway. Penguin. p. 129. ISBN 9781465458902.

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel (2016). Norway. Penguin. p. 129. ISBN 9781465458902.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 200. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Hoffstad, Arne (1976). Sandefjord - byen vår: trekk fra Sandefjordsdistriktets historie under hvalfangsteventyret 1905-1968. Pages 7-9. ISBN 8299038413.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et sted i Sandefjord: lokalhistorisk stedsnavnsleksikon. Sandar historielag. Page 330. ISBN 9788299456753.

- ^ Hoffstad, Arne (1976). Sandefjord - byen vår: trekk fra Sandefjordsdistriktets historie under hvalfangsteventyret 1905-1968. Page 74. ISBN 8299038413.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 299. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Gjerseth, Simen (2016). Nye Sandefjord. Liv forlag. Page 349. ISBN 9788283301137.

- ^ "The Whaling Monument". Visitvestfold.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "County Vestfold". gonorway.no.

- ^ Tønnessen, Johan Nicolay and Arne Odd Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780520039735.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schandy, Tom and Tom Helgesen (2012). Naturperler i Vestfold. Forlaget Tom & Tom v/Schandy. Page 170. ISBN 9788292916148.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 218. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (2000). Sandefjord i bilder / Sandefjord in pictures. Grafisk studio forl. Page 28. ISBN 8290636024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Norway Is Home to a Whaling History Museum". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Joensen, Jóan Pauli (2009). Pilot Whaling in the Faroe Islands: History, Ethnography, Symbol. Faroe University Press. p. 225. ISBN 9789991865256.

- ^ Tønnessen, Johan Nicolay and Arne Odd Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780520039735.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 205. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Bertelsen, Bjørn Enge and Kirsten Alsaker Kjerland (2014). Navigating Colonial Orders: Norwegian Entrepreneurship in Africa and Oceania. Berghahn Books. p. 128. ISBN 9781782385400.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 327. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ "Norvegia II".

- ^ Lund, Fredrik Larsen (2017). Norske utposter. Vega forlag. pp. 618–619. ISBN 978-82-8211-537-7.

- ^ Lund, Fredrik Larsen (2017). Norske utposter. Vega forlag. pp. 665–666. ISBN 978-82-8211-537-7.

- ^ Hoff, Stein (1985). Drømmen om Galapagos: En ukjent norsk utvandrerhistorie. Grøndahl & Søn. pp. 16–18. ISBN 8250407687.

- ^ Lund, Fredrik Larsen (2017). Norske utposter. Vega forlag. pp. 666–667. ISBN 978-82-8211-537-7.

- ^ Headland, Robert (1992). The Island of South Georgia. CUP Archive. p. 130. ISBN 9780521424745.

- ^ http://www.hvalfangstmuseet.no/en/the-beginnings/

- ^ Lund, Fredrik Larsen (2017). Norske utposter. Vega forlag. p. 619. ISBN 978-82-8211-537-7.

- ^ "Lars Christensen". Norsk Polarhistorie. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Norvegia ekspedisjon". Norsk Polarhistorie. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Gazetteer - AADC".

- ^ Barr, Susan (28 September 2014). "Nils Larsen – 2". Nbl.snl.no. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Christophersen, Egil (1989). Vestfold i krig. Bokkomitéen. Pages 16-17. ISBN 9788299199506.

- ^ Holskjær, Lars (2017). Kamper uten tall. Forlagshuset i Vestfold. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9788293407294.

- ^ Holskjær, Lars (2017). Kamper uten tall. Forlagshuset i Vestfold. pp. 121–122. ISBN 9788293407294.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1997). Sandefjords historie B.2: En vanlig småby? Sandefjord kommune. Page 114. ISBN 8299379725.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holskjær, Lars (2017). Kamper uten tall. Forlagshuset i Vestfold. p. 192. ISBN 9788293407294.

- ^ Steen, Sverre (1974). Kristiansands historie 1914–1945. Christianssands sparebank. p. 544.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1997). Sandefjords historie. B. 2: En vanlig småby? Sandefjord kommune. Page 119. ISBN 8299379725.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1997). Sandefjords historie. B. 2: En vanlig småby? Sandefjord kommune. Page 119. ISBN 8299379725.

- ^ "Sandefjord – Kommunesammenslåing". 9 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 8. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 208. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 116. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 136. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 72. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. p. 165. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 111. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 80. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 85. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Olstad, Finn (1995). Sandefjords historie Bind 1: Strandsitter og verdensborger. Sandefjord Kommune. Page 295. ISBN 9788299059572.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kilde for 1801, 1865, 1875 og 1900: www.digitalarkivet.no

- ^ Kilde for 1825: vf.disnorge.no

- ^ Kilde for 1951–2008: Statistics Norway

- ^ "Folkemengd 1. januar 2011 og endringane i 2010. Endelege tal". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Sandefjords Blad – SAS går inn i historien med et smell". Sandefjords Blad. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "01222: Endringar i befolkninga i løpet av kvartalet, for kommunar, fylke og heile landet (K) 1997K4 - 2021K1".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jøranlid, Marianne (1996). 40 trivelige turer i Sandefjord og omegn. Vett Viten. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9788241202841.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. p. 3. ISBN 978-82-994567-5-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1985). Sandefjord: A modern city with vast potential. Grafisk Studio. p. 4. ISBN 82-90636-00-8.

- ^ "Skagerak International School: Life in Sandefjord". Skagerak.org. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et sted i Sandefjord: lokalhistorisk stedsnavnsleksikon. Sandar historielag. p. 100. ISBN 9788299456753.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Lundbo, Sten (24 October 2017). "Sandefjord". Great Norwegian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Video Sandefjord City". Gonorway.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (2000). Sandefjord i bilder / Sandefjord in pictures. Grafisk studio forl. Page 143. ISBN 8290636024.

- ^ Jøranlid, Marianne (1996). 40 trivelige turer i Sandefjord og omegn. Vett Viten. p. 29. ISBN 9788241202841.

- ^ Gjerseth, Simen (2016). Nye Sandefjord. Liv forlag. Page 234. ISBN 9788283301137.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-82-994567-5-3.

- ^ Jøranlid, Marianne (1996). 40 trivelige turer i Sandefjord og omegn. Vett Viten. p. 45. ISBN 9788241202841.

- ^ "Høyeste fjelltopp i hver kommune – Kartverket". 15 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2011). På Tur i Vestfold del 2. E-forlag. pp. 202–204. ISBN 9788293057222.

- ^ Schandy, Tom and Tom Helgesen (2012). Naturperler i Vestfold. Forlaget Tom & Tom v/Schandy. Page 171. ISBN 9788292916148.

- ^ Nikel, David (2017). Moon Oslo. Moon Travel Guides. p. 95. ISBN 978-1631216619.

- ^ Berezin, Henrik (2011). Norway Travel Adventures. Hunter Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9781588437068.

- ^ Great Britain. Hydrographic Dept. (1880). The Norway Pilot, Part 2. J. D. Potter. p. 8.