Sayfo

The Sayfo or Seyfo (Neo-Aramaic: ܣܝܦܐ [ˈsajfoʔ] lit. 'sword'; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Syriac Christians (mostly belonging to the Syriac Orthodox Church, Church of the East, or Chaldean Catholic Church) in eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire, and neighbouring regions of Persia, committed by Ottoman troops and some Kurdish tribes during World War I. The Sayfo mostly occurred between June and October 1915, concurrently with and closely related to the Armenian genocide, although it is considered less systematic.

Mass killing of Assyrian civilians began during the Ottoman occupation of Persia from January to May 1915, during which massacres were committed by Ottoman irregulars and Kurdish tribes. In Bitlis Vilayet, Ottoman troops returning from Iran combined with local Kurdish tribes to massacre the local Christian population, including Assyrians. In mid-1915, Ottoman forces as well as Kurds jointly attacked the Assyrian tribes of Hakkari, driving them out by September. In Diyarbekir vilayet, governor Mehmed Reshid initiated a genocide encompassing all of the Christian religious groups in the vilayet, including Syriac Christians. Ottoman Assyrians living farther south in present-day Iraq were not subjected to mass killing.

At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the Assyro-Chaldean delegation stated that its losses were 250,000, about half its prewar population. The Sayfo is comparatively less well-studied than the Armenian genocide. Efforts to have the Sayfo formally recognized as a genocide began in the 1990s and have been spearheaded by the Assyrian diaspora. Several countries have recognized that Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire were victims of a genocide, but Turkey denies that an Assyrian genocide took place.

Terminology

Terms for Syriac Christians such as "Assyrian", "Syriac", "Aramean", and "Chaldean" have become politicized, and there is no universally accepted term.[1] Historian David Gaunt states that there was no consensus among English-language sources what term to use for the ethnic group in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, since the Ottoman Empire was organized by religion, "Assyrian was never used by the Ottomans; rather, government and military documents referred to their targets by their traditional sectarian names. Thus, speaking of an 'Assyrian Genocide' is anachronistic".[2]

In Neo-Aramaic, the genocide is usually called Sayfo or Seyfo (ܣܝܦܐ), a cognate of the Arabic saif meaning "sword", which since the tenth century has also meant "extermination" or "extinction".[3][4] This word appears in such expressions as "Year of the Sword", referring to 1915,[4] and "sword of Islam", as Syriacs believed that their extermination was motivated by religion.[5]

Background

The people now called Assyrian, Chaldean, or Aramean—in Neo-Aramaic, Suryoye or Suryaye—probably originate in heterogenous populations native to eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia that converted to Christianity in the first centuries CE, prior to the Roman Empire's adoption of Christianity. These populations historically spoke Aramaic languages and used Classical Syriac as a liturgical language. The first major schism within Syriac Christianity dates to 410, when Christians in the Sassanid Empire (Persia) formed the Church of the East to distinguish themselves from the official religion of the Byzantine Empire.[6] The East Syriac Rite churches trace their descent from this church, as opposed to those that use the West Syriac Rite, which developed within the Byzantine Empire.[7]

Following the condemnation of Archbishop Nestorius of Constantinople, Nestorius fled to Persia, and the Church of the East ultimately adopted a dyophysite Christology that was similar to Nestorius'.[7] The West Syriac church opposed both Nestorian Christology and the Chalcedonian Definition adopted by the Byzantine church in 451, instead insisting on miaphysitism; consequently it faced persecution from Byzantine rulers. The Bishop of Edessa, Jacob Baradaeus (c. 500–578), set up the independent institutions of the Syriac Orthodox Church. The schisms in Syriac Christianity were fueled by political divisions between different empires and personal antagonisms between clergymen.[7]

At the time of the Islamic conquest, Syriac Christians hoped for a respite in religious persecution that they faced. Under Muslim rule, they had the status of dhimmis, had to pay the jizya and faced restrictions that did not apply to Muslims, but made up a majority in some areas. However, due to the unsuccessful Crusades and the Mongol invasions, the indigenous Christian communities of the Middle East were devastated. Decline fueled additional schisms; in the sixteenth and seventeenth century the Chaldean Catholic Church and Syriac Catholic Church split from the Church of the East and Syriac Orthodox Church respectively, entering into full communion with the Catholic Church. Each church considered the others as heretical.[8] Due to these deep divisions, Assyrians were unable to coordinate a unified resistance effort when they were targeted for extermination.[9]

Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire

Because of the millet system, the Ottoman Empire did not recognize ethnic groups, instead different religious denominations, organized as millets: Süryaniler/Yakubiler (Syriac Orthodox), Nasturiler (Church of the East), and Keldaniler (Chaldean Catholic Church).[8][2] Until the nineteenth century, these groups belonged to the Armenian millet.[10][11]

Gaunt has estimated the Assyrian population at between 500,000 and 600,000 just before the outbreak of World War I, significantly higher than reported on Ottoman census figures. Midyat was the only town in the Ottoman Empire with an Assyrian majority, although divided between Syriac Orthodox, Chaldeans, and Protestants.[12] Syriac Orthodox Christians were concentrated in the hilly rural areas around Midyat, known as Tur Abdin, where they populated almost 100 villages and worked in agriculture or crafts.[12][13] Syriac Orthodox culture was centered in two monasteries near Mardin, Mor Gabriel and Deyrulzafaran.[14] Outside of the area of core Syriac settlement, there were also sizable populations in the towns of Urfa, Harput, and Adiyaman.[15]

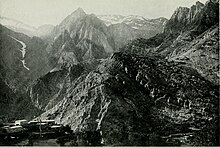

Under the leadership of the Patriarch of the Church of the East, Assyrian tribes ruled the Hakkari mountains with aşiret status—in theory granting them full autonomy—with subordinated farmers.[12] Church of the East settlement began to the east on the western shore of Lake Urmia in Iran, in the town of Urmia and surrounding villages; just north, in Salamas, was a Chaldean enclave. There was a Chaldean area around Siirt in Bitlis Vilayet, but the bulk of Chaldeans lived farther south, in modern-day Iraq and outside of the zone that suffered genocide during World War I.[16]

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, some Assyrians began to develop national awareness and shortly before World War I some intellectuals began to propose the unification of all Assyrians regardless of religion. Such national feelings sometimes meant a quest for autonomy or independence or for others were compatible with national belonging in the state that they lived in.[17]

Worsening conflicts

While Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated, this "integration was not peaceful; rather it led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest."[18] During the decades prior to World War I, Assyrians' situation worsened as they suffered increasing attacks by their neighbors, which the Ottoman government did not prevent. These attacks aimed to appropriate land and property, but also had a religious aspect, in which Christians were forced to choose between conversion to Islam and death.[19]

The first mass killing targeting Assyrians specifically was the massacres of Badr Khan in the 1840s, during which Kurdish emir Badr Khan repeatedly invaded the Hakkari mountains to attack Assyrian tribes there, killing several thousands.[19][20] The irregular Hamidiye cavalry, formed from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government, (although they feuded with each other) were exempt from both civil and military law, enabling them to commit violence with impunity. During intertribal feuds, the brunt of violence was directed at Christian villages under the "protection" of the opposing tribe.[21]

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When Kurds refused to give the weapons back at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were left at a disadvantage and subjected to increasing violence. The rise of political Islam in the form of Kurdish shaikhs also widened the gulf between Assyrians and Muslim Kurds.[22] Many Assyrians were killed in the 1895 massacres of Diyarbekir during the Hamidian massacres.[19] Violence worsened after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, despite Assyrian hopes that the new government would stop promoting anti-Christian Islamist sentiments.[23][24] Due to increasing Kurdish attacks, which the Ottoman authorities did nothing to prevent, the Patriarch of the Church of the East, Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin, entered into negotiations with the Russian Empire prior to World War I.[12]

World War I

Prior to World War I, Russia and the Ottoman Empire both courted populations living in the other's territory to rely on to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. While the Ottoman Empire tried to enlist Caucasian Muslims as well as Armenians, Iranian Assyrians and Azeris, Russia looked to Armenians, Kurds, and Assyrians living in the Ottoman Empire.[25] In particular, the Ottoman Empire wanted to annex Iranian Azerbaijan, the northwestern part of Qajar Iran, in order to connect with the Russian Azeris and even realize Pan-Turanism.[26]

Years before the war, CUP politician Enver Pasha set up the paramilitary Special Organization, personally loyal to himself. Its members, many of whom were convicted criminals released from prison for the task, operated as spies and saboteurs.[27] On 24 July 1914, the Ottoman Empire ordered a full mobilization for war; shortly thereafter, it concluded the German–Ottoman alliance.[28] In August 1914, the CUP sent a delegation to a Dashnak conference, offering an autonomous Armenian region if the Dashnaks incited a pro-Ottoman revolt in Russia in the event of war. The Armenians refused. Gaunt states that it is likely a similar offer was made to Mar Shimun during a meeting with Tahsin Bey in Van on 3 August. After returning, he sent letters urging his followers to "fulfill strictly all their duties to the Turks" and see if they were prepared to keep their promises.[29] In late 1914, Assyrians of Hakkari and Iran refused conscription into the Ottoman army,[30] but those in Mardin accepted conscription.[31]

Assyrian volunteers

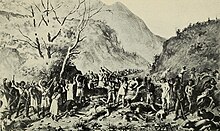

In reaction to the Assyrian Genocide and lured by British and Russian promises of an independent nation, the Assyrians led mainly by Agha Petros of Baz, Malik Khoshaba of Tyari and several tribal leaders known as Maliks (Syriac: ܡܠܟ), fought alongside the Allies against Ottoman forces known as the Assyrian volunteers or Our Smallest Ally. Despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned the Assyrians fought successfully, scoring a number of victories over the Turks and Kurds. This situation continued until their Russian allies left the war, and Armenian resistance broke, leaving the Assyrians surrounded, isolated and cut off from lines of supply. The sizable Assyrian presence in south eastern Anatolia which had endured for over four millennia was thus reduced significantly by the end of World War I.[32][33]

Ottoman occupation of Urmia (January to May 1915)

Prior to the war, Russia estimated that 40 percent of the percent of Urmia province were Christian, including 50,000 Armenians and 75,000 Assyrians.[34] Facing attacks from Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages organized self defense with the result that by World War I they were well armed.[35] In 1914, prior to the official declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. In late September and October 1914 the attacks were on a large scale and once the attackers came close to Urmia; many Assyrian villages were attacked.[36] Due to Ottoman attacks thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia.[37] Others arrived in Iran after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 Ottoman jihad proclamation enflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Iranian border area and convinced the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans.[38] In November, Persia declared its neutrality but that was not respected by the warring parties.[35]

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster Russian forces in the area against Ottoman attack.[39] Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente and paraded in Urmia. Agha Petros later stated that he received promises from Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war.[40] Ottoman irregulars in Van vilayet crossed the Persian border and attacked Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in Khoi, Tabriz, and Urmia and expelled some Sunni Muslims. The Ottoman authorities retaliated with the expulsion of several thousand Hakkari Assyrians to Persia. Resettled in farming villages, these Assyrians were armed by Russia.[41]

On 1 January 1915, Russia, which had been occupying Iranian Azerbaijan, abruptly withdrew its forces. Ottoman forces led by Djevdet Bey, Kazim Karabekir, and occupied it with no opposition.[42] Immediately after the withdrawal of Russian forces, local Muslims committed pogroms against Christians; the Ottoman army also attacked Christian civilians. Altogether more than a dozen villages were sacked and, of large villages, only Gulpashan was left intact. News of these atrocities spread quickly leading many Armenians and Assyrians to flee to the Russian Caucasus; those from north of Urmia had more time to flee.[43] According to different estimates some 15,000 to 20,000 managed to cross the border into Russia.[44] Those Assyrians who had volunteered for service in the Russian forces were separated from their families, often left behind.[45] An estimated 15,000 Ottoman troops reached Urmia by 4 or 5 January and Salmas on 8 January.[46][47]

Massacres

The Ottoman troops attacked Christian villages during their retreat, beginning in February 1915, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack.[48] Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining the existence of a widespread Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians in order to reduce the potential future strength of the volunteer units.[49] Some Iranian Kurdish tribes participated in the killings although other local Kurds protected Christian civilians.[50] In addition, some Assyrian villages engaged in armed resistance when attacked.[46] The Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs made a formal protest of the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.[51][52]

There were no missionaries in Salmas valley to protect Christians; although some local Muslims attempted to do so. In Dilman, the Iranian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians but was forced to surrender the men to the Ottoman forces, who executed them in the town square. In February 1915,[53] the entire Christian male population, between 700 and 800 people, was murdered in Haftevan over two days. The Ottoman forces, realizing that they could not prevent the Russian advance, lured Christians to the village by demanding that they register there, and also arrested notables in Dilman, who were brought to Haftevan for execution. The killings were committed jointly by the Ottoman army, led by Djevdet, and the local Shekak Kurdish tribe led by Simko Agha.[54] Gaunt argues that the massacre in Haftevan was the first premeditated mass execution of civilians by the Ottoman forces in the Caucasus campaign. Historian Florence Hellot-Bellier considers this massacre as well as the one in nearby Khosrowa to be "clearly related to the extermination orders from Constantinople".[55]

Most Christians in Urmia did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal.[56] Around 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were left stranded in Urmia.[51] Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the Presbyterian and Lazarist missions of Urmia. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease.[57] Between February and May, when Ottoman forces pulled out, there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia.[51] More than a hundred men were arrested at the Lazarist compound and dozens, including Mar Dinkha, the Bishop of Tergawer, executed on 23 and 24 February.[53] Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked with men killed and women and children abducted and raped.[58][59]

In April, Halil Kut arrived with reinforcements following a forced march from Rowanduz. Both he and Djevdet ordered the murder of Armenian and Syriac soldiers serving in the Ottoman army; several hundred were killed as a result.[60][61] There were several other massacres killing hundreds of Christians,[62] and women were targeted for kidnapping and rape.[63][64] One German observer estimated that 21,000 Christians were killed in Iranian Azerbaijan between December and February.[64] In May and June, those Christians who had fled to the Caucasus returned to find their villages destroyed.[55] Following the discovery of the atrocities, Russian vice-consul Pavel Vvedensky noted that it had become difficult to prevent the Armenian and Assyrian volunteers from taking revenge on Muslims.[65] Iranian sources report revenge attacks against civilians by Armenian volunteers and Assyrians from the Jilu tribe.[66] After retreating from Iran, the Ottoman forces—blaming Armenians and Assyrians for their defeat—took revenge against Ottoman Christians.[51]

Ethnic cleansing of Hakkari

Massacres of Assyrians in the lowlands

In August 1914, Assyrians in nine villages were forced to flee to Iran and their villages were burned after refusing conscription into the Ottoman army.[67] On 26 October 1914, a few days before the Ottoman Empire officially entered World War I, Talaat sent a telegram to Djevdet, ordering the deportation of the Assyrians who lived near the Iranian border. In the context of a planned Ottoman attack in Iran, the loyalty of the Hakkari Assyrians was doubted. The order envisioned the resettlement of Assyrians among Muslims in Anatolia with no more than twenty living in each place, such that their culture, language, and traditional way of life would be destroyed.[68][69][70] The government in Van reported that the order could not be implemented due to the lack of forces to carry it out, and by 5 November, the expected Assyrian unrest did not materialize.[71] There were arrests and some killings of Assyrians in Julamerk and Gawar while Ottoman irregulars attacked Assyrian villages throughout Hakkari in retaliation for their refusal to follow the order. Until December 1914, Assyrians were unaware of the government's role in these events, and formally protested to the governor of Van.[70]

In Bashkale, the Ottoman garrison was commanded by Kazim Karabekir and the local SO commanded by Ömer Naji. In November 1914, Russian forces captured the town as well as Sarai and held both for a few days. After recapture by the Ottomans, local Christians were punished as collaborators out of proportion to any collaboration that took place. Y. K. Rushdouni reported that 12 Armenian and Assyrian villages "were ruthlessly wiped out".[72][73] Local Ottoman forces consisting of gendarmerie, Hamidiye irregulars, and Kurdish volunteers were unable to mount attacks on the Assyrian tribes on the highlands, confining their attacks to poorly armed Christian villages in the plains. Refugees from the area told the Russian army that "nearly the entire male Christian population of Gawar and Bashkale" had been massacred.[74] In May 1915, Ottoman forces retreating from Bashakale committed another massacre of hundreds of Armenian women and children before continuing on to Siirt.[75]

Preparations for war

In the patriarch's home in Qudshanis, Mar Shimun reported that "When we saw many Christians of Gawar and killed without reason, we thought our turn would come". Via Agha Petros, an Assyrian interpreter for the Russian consulate in Urmia, he made contact with the Russian authorities. In December 1914, Mar Shimun was also called to a meeting with Shefik Bey, an Ottoman official sent from Mardin to win over the Assyrians for the Ottoman cause, in Bashkale. Shefik promised protection and money in exchange for a written promise that the Assyrians would not side with Russia or permit Nestorian tribes from taking up arms against the Ottoman government. The tribal chiefs considered this offer but rejected it.[76]

In January 1915, Kurds blocked the path from Qudshanis to the Assyrian tribes. The next month, the patriarch's sister Lady Surma left Qudshanis with 300 men.[77] By early that year, the tribes of Hakkari were preparing to defend themselves from a large-scale attack. After a council, they decided to send women and children to the area around Chamba in Upper Tyari, leaving only combatants behind.[78] On 10 May, the Assyrian tribes met and made some sort of declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire, or alternately a general mobilization.[79] , the head of the Jilu tribe, had maintained good relationships with the Ottoman authorities and the other tribal leaders felt that they could not trust him. On 22 May, he and six companions were killed in an ambush orchestrated by Mar Shimun. Events subsequently proved that Jilu had no secret deal with the Ottomans as they were the first to be attacked and driven out of Hakkari.[80] In June, Mar Shimun traveled to Persia to ask for the support of the Russians. In (Salmas valley), he met with General Fyodor Chernozubov who promised support. The patriarch and Agha Petros also met Russian consul Basil Nikitin in Salmas just before 21 June. However, the promised Russian help never materialized.[77]

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force rushed to relieve the defense of Van. As a result, , the vali of Mosul, was given special powers to invade Hakkari. Talat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands".[81] The ethnic cleansing operation was jointly coordinated by Enver and Talat and both military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul vilayet.[82] The Ottoman army joined forces with local Kurdish tribes, given specific targets: Suto Agha of the Kurdish attacked Jilu, , and Baz from the east; Said Agha attacked a valley in Lower Tyari; Ismael Agha targeted Chamba in Upper Tyari; and the Upper Berwar emir, from the west, attacked Ashita, the , and Lower Tyari.[75]

Invasion of the highlands

The joint encirclement operation was launched on 11 June.[75] The Jilu tribe was attacked at the beginning of the campaign by several Kurdish tribes; the fourth-century church of was destroyed with historic artifacts. Ottoman forces based in Julamerk and Mosul launched their joint attack on Tyari on 23 June.[75][83] Haydar first attacked the Tyari villages of Ashita and Sarespido and later on an expeditionary force of three thousand Turks and Kurds attacked the mountain pass between Tyari and Tkhuma. In most of the battles, Assyrians were victorious but incurred unsustainable losses of lives and ammunition, they lacked the modern German-manufactured rifles, machine guns, and artillery used by the attacking force.[84] In July, Mar Shimun sent Malik Khoshaba and bishop Mar Yalda Yahwallah from Barwar to Tabriz to request urgent assistance from the Russians.[83] The Kurdish Barzani tribe assisted the Ottoman army and laid waste to Tkhuma, Tyari, Jilu, and Baz.[85] During the campaign, Ottoman forces took no prisoners.[86] Mar Shimun's brother Hormuz was arrested where he was studying in Constantinople and in late June, Talat attempted to obtain the surrender of the Assyrian tribes by threatening his life if Mar Shimun did not capitulate. The Assyrians refused to, so he was killed.[87][88]

Outnumbered and outgunned, the Assyrians retreated further into the high mountains where there was no food[89][85] and watched as their homes, farms, and herds were pillaged.[86] They were left with no other options than fleeing to Persia, which most had done by September. Most of the men joined the Russian army, hoping therefore to return home.[85][90] It is not known how many died fighting in Hakkari.[91] Nikitin estimated that 45,000 Assyrians reached Persia, out of a little over 70,000 from the Assyrian tribes of Hakkari before the war.[92] Many died the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care. They attempted to fight their way back home several times during and after the war, but never succeeded.[91] According to Gaunt, it is inaccurate to term the invasion of Hakkari as a civil war as the Assyrians were not fighting for control of the central government but instead their only strategic objective was defensive.[93] In contrast, the Ottoman goal was not merely to militarily defeat the Assyrian tribes but completely expel them and prevent their return.[94]

Butcher battalion in Bitlis (June 1915)

In Bitlis, a Kurdish rebellion was put down shortly before the official outbreak of war in November 1914. The CUP government reversed its position on the Hamidiye regiments, raising them to put down the rebellion.[95][96] As occurred elsewhere, military requisitions turned into general pillage.[95][97] In February, those recruited into labor battalions began to disappear.[98] In July and August 1915, 2,000 Chaldeans from Bitlis vilayet, as well as some Syriac Orthodox, were among those who fled into the Caucasus when the Russian army retreated from Van.[99]

Siirt

Prior to the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were a Christian enclave populated largely by Chaldean Catholics.[100] The Chaldean diocese of Siirt was totally destroyed during the Sayfo, along with its library containing rare manuscripts.[101] estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt sanjak including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox.[102] Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notables, including Chaldean bishop Addai Sher.[103][104] After retreating from Persia, Djevdet led the siege of Van and in June continued to Bitlis with 8,000 soldiers who he termed the "butcher battalion" (Turkish: kassablar taburu).[105] Arrival of these troops led to the escalation of violence.[104] Both the mutesarif and the mayor of Siirt—Serfiçeli Hilmi Bey and Abdul Ressak—were replaced due to their lack of support for the killing.[106][107] Forty local officials in Siirt were very active in organizing the massacres.[103]

During a systematic massacre that lasted a month, people were killed in the streets or their houses, which were plundered.[102] The massacre was organized by the vali of Bitlis, the chief of police, the mayor, and other local notables.[108] The killing in the town of Siirt was done by çetes, while the surrounding villages were destroyed by Kurds;[102] Gaunt states that "a very large number of the neighboring Kurdish tribes participated".[109] According to eyewitness Rafael de Nogales, the massacre was planned ahead of time as revenge for Ottoman defeats at the hands of Russia.[102] Only 400 people were officially deported from Siirt, the remainder having been either killed or kidnapped by Muslims.[104] These deportees (women and children, as all the men had been executed) were forced to march away from Siirt in different directions, assaulted by gendarmes.[110] As they passed through different areas, all possessions including clothing were gradually stolen by the local Kurdish and Turkish populations. Women considered attractive were taken away by gendarmes or Kurds, raped, and killed; those unable to keep up were also killed.[111] One of the places where they were attacked and robbed by Kurds was the gorge of Wadi Wawela in Sawro kaza, northeast of Mardin.[112] Only 50[104] or 100 survivors arrived in Mosul out of an original 7,000 to 8,000 Chaldeans.[113] Only three Assyrian villages in Siirt—Dentas, Piroze and Hertevin—survived the Sayfo, existing until 1968 when their residents emigrated.[114]

After leaving Siirt, Djevdet proceeded to Bitlis, arriving on 25 June; his forces killed men with their women and girls taken as slaves by Turks and Kurds.[115] The Syriac Orthodox Church estimated its losses at 8,500 people in Bitlis vilayet, mainly in Schirwan and Gharzan.[116]

Diyarbekir

The situation in Diyarbekir worsened over the winter of 1914–1915 as the Saint Ephraim church was vandalized and four young men from the Syriac village of were hanged on charges of desertion. Syriacs who gathered to protest the execution were clubbed by gendarmes and two died as a result.[117][118] In March, many non-Muslim soldiers were disarmed and transferred to labor battalions where they were put to work building roads. Harsh conditions, mistreatment, and individual murders led to many deaths.[119]

On 25 March, governor Hamid Bey was replaced by Mehmed Reshid, one of the founding members of the CUP.[120][121] Chosen for his previous record in perpetrating anti-Armenian violence,[122] Reshid brought along thirty mostly Circassian Special Organization members who were joined by convicts released from the prison.[120] On 6 April, following Talat's order, Reshid replaced the moderate mayor of Diyarbekir with , an anti-Armenian radical.[123] Many local officials (kaymakams and mutesarifs) refused to follow Reshid's orders and were replaced in May and June 1915.[124] Kurdish confederations were pressured into allowing their Assyrian clients to be killed. Those allied with the government complied (including the Milli and ), but those opposed to it—especially the —sometimes resisted.[125]

Under Reshid's leadership, a systematic anti-Christian extermination took place in Diyarbekir vilayet.[126] Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör states that, in Diyarbekir, "most instances of massacre in which the militia engaged were directly ordered by" Reshid and that "all Christian communities of Diyarbekir were equally hit by the genocide, although the Armenians were often particularly singled out for immediate destruction".[127] According Rhétoré's estimates, Syriac Orthodox in Diyarbekir lost 72 percent of their population, compared to 92 percent of Armenian Catholics and 97 percent of Armenian Apostolic Church adherents.[128] In September 1915, Reshid reported the deportation of 120,000 "Armenians" from the vilayet, exceeding their prewar population.[129]

On 12 July 1915, Talat telegraphed Reshid, ordering that "measures adopted against the Armenians are absolutely not to be extended to other Christians ... you are ordered to out an immediate end to these acts".[130] No action was taken against Reshid for exterminating non-Armenian Christians, or even assassinating Ottoman officials who disagreed with the massacres, and in 1916 he was rewarded by appointment as governor of Ankara. As a consequence, it is debatable whether Talat's telegram was sent to appease German an Austrian opposition to the massacres and not intended to be implemented.[124][130] Historian Raymond Kévorkian argues that the genocide of Syriac Christians in Diyarbekir was likely ordered by the .[124]

Assyrian resistance in Tur Abdin

In Tur Abdin, there were some instances of Syriac Christians fighting against their attempted extermination.[131] One of the best documented cases was the defense of the Syriac Orthodox village of Azakh (now İdil), where the local Syriac Orthodox population, joined by a small number of Armenians and Chaldeans who fled from elsewhere, chose to make their stand as Azakh was a defensible location. Kurdish tribes launched major attacks against surrounding Syriac villages in June and July 1915 in order to confiscate land. Azakh was first attacked on 18 August, but the defenders repelled the attack as well as subsequent attacks. Against the advice of general Mahmud Kâmil Pasha, Enver ordered the rebellion to be immediately crushed in November.[132] German general Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz and the German ambassador, Konstantin von Neurath, informed Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg of an Ottoman request for German assistance in crushing the resistance. The Germans refused, fearing that it would be cited by the Ottomans to insinuate that Germans had initiated the anti-Christian atrocities. The defenders launched a surprise attack on Ottoman troops during the night of November 13–14, which led to a truce that ended the resistance on favorable terms for the villagers.[133]

These events, termed "rebellions" by Ottoman officials, were defense against aggression and represented the Christians trying to save their own lives. On 25 December 1915, the Ottoman government decreed that "Instead of deporting all of the Syriac people" they were to be confined "in their present locations".[134] By this time most of Tur Abdin was in ruins with the exception of villages that resisted and some families that found refuge in monasteries.[130]

Aftermath

| External image | |

|---|---|

Following their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians were resettled by the Russian occupation authorities, with their herds, around Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Their presence incurred the resentment of locals for worsening living standards. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war following the Russian Revolution made prospects of a return to Hakkari grow even more dim.[90][135] From then on, the Assyrian militias that had been fighting under Russian command united with Armenians.[90][135] From February to July 1918, the region was engulfed by ethnic violence. In February, violent riots cost the lives of many Muslims. In March, Mar Shimun was assassinated by the Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak. This was followed by massacres of Christian in Salmas in June and in Urmia in early July[136] and large-scale abduction of Assyrian women.[63]

Assyrians, both those from the Ottoman Empire and those from Persian, fled to Hamadan, where the British had a garrison, on 18 July 1918 to escape death at the hands of Ottoman forces commanded by Ali İhsan Pasha.[136][137] Some remained in Persia, but there was a renewed anti-Christian insurrection in May 1919.[136] Hellot-Bellier says "The massacres of 1918 and 1919 demonstrate the degree of violence and resentment which had accumulated throughout all of these years of war and the break-up of the long-standing links between the inhabitants of the Urmia region".[83]

During the journey to Hamadan, the Assyrians were harassed by Kurdish irregulars and others died of exhaustion. Many were killed near Heydarabad[disambiguation needed] and another 5,000 during an ambush by Ottoman forces and Kurdish irregulars near Sahin Ghal’e mountain pass.[138] Entirely dependent on the British for protection, they were resettled in a refugee camp in Baqubah, which held fifteen thousand Armenians and thirty-five thousand Assyrians in October 1918.[139] The camp was attacked by Arabs and defended by Agha Petros. In 1920, it was shut down and Assyrians hoping to return to Urmia or Hakkari were sent northwards to Mindan. Agha Petros led a group of Assyrians from Tyari and Tkhuma seeking to return, but was repulsed by Rashid Bek, the chieftain of Barwar. About 4,500 Assyrians were resettled around Duhok and Aqrah.[140] Some Assyrians managed to return to Hakkari but were driven out again in 1924 by a Turkish army commanded by Kazim Karabekir.[90]

Paris Peace Conference

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (July 2021) |

Assyrians felt betrayed after the war that the promises of an Assyrian homeland that had been made in exchange for their support of the Allies were not fulfilled by the British, despite the high price that they paid for fighting on the Allied side during the war.[141]

Death toll

Assyrian delegates at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference stated that their losses were 250,000 for both the Ottoman Empire and Persia, around half the prewar population. In 1923, at the Lausanne Conference, they changed their estimate to 275,000. Gaunt states that "the accuracy of these figures has proven impossible to check—and given the nature of the peace conference and the desire of the Christians to be compensated for the extent of their suffering, it would have been natural for them to have exaggerated the figures".[142] In comparison with the Armenian genocide, the Sayfo was less systematic. In some places, all Christians were killed equally, but elsewhere, local officials spared Syriacs while targeting Armenians.[30] Although in most places where they were targeted, Christians were killed without resistance, when they resisted, the Ottoman authorities at the highest level directly ordered attacks on Syriac Christians.[143] In some areas, more than 50 percent of Syriacs were killed, but in Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra, the mostly Chaldean population was left intact.[144] Gaunt states, "The manner in which people were murdered was, in places, extreme and proceeded by gratuitous public humiliation of the victims and their families."[130]

| Persia | 40,000 |

| Van vilayet (including Hakkari) | 80,000 |

| Diyarbekir vilayet | 63,000 |

| Harput vilayet | 15,000 |

| Bitlis vilayet | 38,000 |

| Adana vilayet, Der Zor and elsewhere | 5,000 |

| Urfa sanjak | 9,000 |

International response

Ottoman atrocities in Iran were widely covered in international media in mid-March 1915.[49] The Blue Book, a collection of eyewitness reports published by the British government in 1916, contained 104 pages of its 684 pages about the fate of Assyrians. The original title mentioned Assyrians, but the eventual title was The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.[146]

Legacy

In historiography, the Sayfo has been considered both as a , emphasizing growing role of ideology and nationalism in causing the genocide, and a colonial genocide, a mixture of killing and expulsion committed to redistribute land and property to a different population.[147][148] Gaunt argues that the Sayfo is "one of the least known genocides of modern times", in part because its targets were divided between mutually antagonistic churches and did not develop a collective identity.[149] It was closely related to the Armenian genocide, but remains much less known.[150]

In Assyrian collective memory

For Assyrians, the Sayfo is considered the greatest example of persecution of Assyrians in the modern era.[151] Assyrian survivors narrated their experiences by referencing local conditions such as desire for land and Islamic fanaticism, not understanding the broader political context.[149] Eyewitness accounts of the genocide were typically passed down in an oral tradition rather than in written form.[152] Memories of the genocide were often passed down in lamentations.[153] Following large-scale migration to Western countries in the second half of the twentieth century, where Assyrians enjoyed greater freedom of speech, survivor accounts began to be communicated more publicly especially by grandchildren of the survivors.[154] Additional songs were written by the descendants of the victims and recorded by Assyrians living in the diaspora, but being written in Neo-Aramaic they did not reach a broader audience.[155] Later on, Western languages and non-traditional song styles such as rap began to be used to by Assyrians to communicate about the Sayfo.[156]

International recognition

Beginning in the 1990s, prior to the first academic research on the genocide, Assyrian diaspora groups began the quest for formal recognition of the Sayfo as genocide, patterned off earlier campaigns for Armenian genocide recognition.[143][157] The Sayfo is recognized as a genocide by resolutions passed by the parliaments of Sweden (in 2010);[158][159] Armenia,[160] the Netherlands,[161] and Austria (in 2015);[162] Germany (in 2016)[163] and Syria (in 2020).[164][165] As of 2020, three American state legislatures (Arizona, California, and New York) have passed resolutions that officially recognize the Assyrian genocide. Ten other legislatures (Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington D.C., and West Virginia) have passed resolutions that recognize the Armenian genocide, but acknowledge the Assyrian victims in their text.[166] In December 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars passed a resolution officially recognizing the Assyrian genocide.[167][151][168]

Memorials

There are monuments commemorating the victims of the Assyrian genocide in Armenia, Australia, Belgium, France, Greece, Sweden, Ukraine, and the United States.[169] On 15 December 2009, Fairfield City Council, a local government area of Sydney, Australia where many residents are of Assyrian descent, granted permission for Assyrian Universal Alliance to build a memorial to the genocide on land owned by the council. Its construction was opposed by the Turkish government and by Turkish-Australians. The memorial was unveiled on 7 August 2010, .[170]

Denial

After the 1915 genocide, the Turkish government was initially successful at silencing discussion of it in high culture and written works.[152] Non-Turkish music and poetry were suppressed, and the Syriac Orthodox Church discouraged discussion of the Sayfo for fear of reprisals from the Turkish government.[171] Those who seek to justify the destruction of Assyrian communities in the Ottoman Empire cite military resistance of some Assyrians against the Ottoman government. Gaunt, Atto, and Barthoma state that "under no circumstances are states allowed to annihilate an entire population simply because it refuses to comply with a hostile government order to vacate their ancestral homes".[172] In Turkish the Sayfo is often called a "so-called genocide" (Turkish: sözde soykırım).[173]

In 2000, Syriac Orthodox priest Yusuf Akbulut was recorded by journalists without his knowledge stating: "At that time it was not only the Armenians but also the Assyrians [Süryani] who were massacred on the grounds that they were Christians". The journalists gave the recording to Turkish prosecutors who charged Akbulut with inciting ethnic hatred based on this statement.[174] In 2001, the National Security Council (Turkish intelligence agency) commissioned a report on the activities of the Assyrian diaspora.[175]

In Turkish academia, the historians Mehmet Çelik and Bülent Özdemir are the main exponents of the idea that there was no Assyrian genocide. Çelik claimed in a 2008 interview that Talat Pasha sent instructions "not to bleed the nose of a single Süryani".[176]

Turkish-Australians interviewed by researcher Adriaan Wolvaardt had the same attitude towards the Assyrian genocide as the Armenian genocide, rejecting both as unfounded.[177] Wolvaardt found that raising the issue of the Assyrian genocide is "viewed as a form of hate directed against Turks".[178] Some had considered leaving Fairfield because a memorial to the victims of the Assyrian genocide was built there.[178]

References

Citations

- ^ Murre-van den Berg 2018, p. 770.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Talay 2017, pp. 132, 136.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Talay 2017, p. 136.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 48.

- ^ Gaunt 2013, p. 318.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2015, p. 87.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 19.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Murre-van den Berg 2018, p. 774.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, p. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, p. 59.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, pp. 59, 61.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Gaunt 2013, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murre-van den Berg 2018, p. 775.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 310.

- ^ Wigram, William Ainger (1920). Our Smallest Ally ; Wigram, W[illiam] A[inger] ; A Brief Account of the Assyrian Nation in the Great War. Introd. by General H.H. Austin. Soc. for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- ^ Naayem, Shall This Nation Die?, p. 281

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 112.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, pp. 117, 125.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 250.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 252.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2006, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 119.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 120–121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 126.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 81, 83–84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 127.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 120.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 122.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 254.

- ^ Naby 2017, p. 165.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 255.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 121–122.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Naby 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 227.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2011, p. 248.

- ^ Kaiser, Hilmar (17–18 April 2008). "A Deportation that Did Not Occur" (PDF). Armenian Weekly.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 251.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2011, p. 257.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 137.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 128.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 123, 140.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 142.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hellot-Bellier 2018, p. 129.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gaunt 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2006, p. 312.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2015, p. 94.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Hellot-Bellier 2018, pp. 109, 129.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 122, 300.

- ^ Gaunt 2011, p. 259.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 234.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 37.

- ^ Polatel 2019, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 237.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, pp. xiii, 116–117, 168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2006, p. 251.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 339.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Polatel 2019, p. 132.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 89, 251, 254.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 340.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 255.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 256.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 253.

- ^ Yuhanon 2018, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Yuhanon 2018, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 252.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 198.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Üngör 2011, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Üngör 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 153, 155.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kévorkian 2011, p. 379.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Üngör 2017, p. 35.

- ^ Üngör 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Gaunt 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 365.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gaunt 2015, p. 96.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 90, 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellot 2003, p. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hellot 2003, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 744.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 744–745.

- ^ Hellot 2003, p. 139.

- ^ Hellot 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 88, 96.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2015, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, p. 300.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, p. 99.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaunt 2013, p. 317.

- ^ Kieser & Bloxham 2014, p. 585.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Atto 2016, p. 184.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Atto 2016, p. 185.

- ^ Atto 2016, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Atto 2016, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Atto 2016, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Atto 2016, pp. 198–202.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 212.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, p. 215.

- ^ "Dutch Parliament Recognizes Assyrian, Greek and Armenian Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 10 April 2015.

- ^ "Austrian Parliament Recognizes Armenian, Assyrian, Greek Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 22 April 2015.

- ^ Abraham, Miryam A. (6 June 2016). "German Recognition of Armenian, Assyrian Genocide: History and Politics". Assyrian International News Agency.

- ^ "Syria Passes Resolution Condemning Turkish Genocide of Assyrians, Armenians". Assyrian International News Agency. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Syrian Parliament Adopts Resolution Recognizing the Armenian Genocide". Massis Post. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Assyrian Genocide Recognition in the United States". Assyrian Policy Institute. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 211.

- ^ Wolvaardt 2014, p. 119.

- ^ Atto 2016, pp. 184, 186.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Donef 2017, p. 215.

- ^ Donef 2017, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Donef 2017, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Donef 2017, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Wolvaardt 2014, pp. 118.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wolvaardt 2014, pp. 121.

Sources

Books

- Gaunt, David (2006). Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-301-0.

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85771-930-0.

- Sjöberg, Erik (2016). The Making of the Greek Genocide: Contested Memories of the Ottoman Greek Catastrophe. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-326-2.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1. Lay summary.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2011). The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965522-9.

- Yacoub, Joseph (2016). Year of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide: A History. Hurst. ISBN 978-0-19-063346-2.

Chapters

- Atto, Naures; Barthoma, Soner O. (2017). "Syriac Orthodox Leadership in the Post-Genocide Period (1918–26) and the Removal of the Patriarchate from Turkey". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 113–131. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Bar Abraham, Abdulmesih (2017). "Turkey's Key Arguments in Denying the Assyrian Genocide". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 219–232. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Donef, Racho (2017). "Sayfo and Denialism: A New Field of Activity for Agents of the Turkish Republic". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 205–218. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Gaunt, David; Atto, Naures; Barthoma, Soner O. (2017). "Introduction: Contextualizing the Sayfo in the First World War". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Gaunt, David (2011). "The Ottoman Treatment of the Assyrians". A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 245–259. ISBN 978-0-19-978104-1.

- Gaunt, David (2013). "Failed Identity and the Assyrian Genocide". Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands (illustrated ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00631-8.

- Gaunt, David (2017). "Sayfo Genocide: The Culmination of an Anatolian Culture of Violence". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 54–69. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Hellot, Florence (2003). "La fin d'un monde: les assyro-chaldéens et la première guerre mondiale" [The end of a world: the Assyro-Chaldeans and the First World War]. Chrétiens du monde arabe: un archipel en terre d'Islam [Christians of the Arab world: an archipelago in the land of Islam]. Autrement. pp. 127–145. ISBN 978-2-7467-0390-2.

- Hellot-Bellier, Florence (2018). "The Increasing Violence and the Resistance of Assyrians in Urmia and Hakkari (1900–1915)". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Gorgias Press. pp. 107–134. ISBN 978-1-4632-0730-4.

- Hofmann, Tessa (2018). "The Ottoman Genocide of 1914–1918 against Aramaic-Speaking Christians in Comparative Perspective". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Gorgias Press. pp. 21–40. ISBN 978-1-4632-0730-4.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas; Bloxham, Donald (2014). "Genocide". The Cambridge History of the First World War: Volume 1: Global War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 585–614. ISBN 978-0-511-67566-9.

- Murre-van den Berg, Heleen (2018). "Syriac Identity in the Modern Era". The Syriac World. Routledge. pp. 770–782. ISBN 978-1-317-48211-6.

- Naby, Eden (2017). "Abduction, Rape and Genocide: Urmia's Assyrian Girls and Women". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. Routledge. pp. 158–177. ISBN 978-1-138-28405-0.

- Polatel, Mehmet (2019). "The State, Local Actors and Mass Violence in Bitlis Province". The End of the Ottomans: The Genocide of 1915 and the Politics of Turkish Nationalism. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 119–140. ISBN 978-1-78831-241-7.

- Talay, Shabo (2017). "Sayfo, Firman, Qafle: The First World War from the Perspective of Syriac Christians". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 132–147. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2017). "How Armenian was the 1915 Genocide?". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 33–53. ISBN 978-1-78533-499-3.

- Wolvaardt, Adriaan (2014). "Inclusion and Exclusion: Diasporic Activism and Minority Groups". Muslim Citizens in the West: Spaces and Agents of Inclusion and Exclusion. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 105–124. ISBN 9780754677833.

- Yuhanon, B. Beth (2018). "The Methods of Killing Used in the Assyrian Genocide". Sayfo 1915. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-3996-1.

Journal articles

- Atto, Naures (2016). "What Could Not Be Written: A Study of the Oral Transmission of Sayfo Genocide Memory Among Assyrians". Genocide Studies International. 10 (2): 183–209. doi:10.3138/gsi.10.2.04.

- Biner, Zerrin Özlem (2011). "Multiple imaginations of the state: understanding a mobile conflict about justice and accountability from the perspective of Assyrian–Syriac communities". Citizenship Studies. 15 (3–4): 367–379. doi:10.1080/13621025.2011.564789.

- Gaunt, David (2015). "The Complexity of the Assyrian Genocide". Genocide Studies International. 9 (1): 83–103. doi:10.3138/gsi.9.1.05. ISSN 2291-1847.

- Hellot-Bellier, Florence (2020). "Les relations ambiguës de la France et des Assyro-Chaldéens dans l'histoire. Les mirages de la " protection "". Les Cahiers d'EMAM (in French) (32). doi:10.4000/emam.2912. ISSN 1969-248X.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sayfo |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Assyrian Genocide. |

- Hellot-Bellier, Florence (2014). Chronique de massacres annoncés: les Assyro-Chaldéens d'Iran et du Hakkari face aux ambitions des empires, 1896-1920 (in French). Geuthner. ISBN 978-2-7053-3901-2.

- Kaiser, Hilmar (2014). The Extermination of Armenians in the Diarbekir Region. İstanbul Bilgi University Press. ISBN 978-605-399-333-9.

- Assyrian genocide

- Ethnic cleansing in Asia

- Diyarbekir Vilayet

- Van Vilayet

- History of West Azerbaijan Province

- World War I crimes by the Ottoman Empire

- Massacres of Christians

- Persecution of Assyrians

- Persecution of Christians in the Ottoman Empire

- Massacres in the Ottoman Empire

- Mass murder in 1915

- Ottoman Empire in World War I

- Forced marches

- Persecution by Muslims

- Human rights abuses in Turkey

- Turkish War of Independence