Sex organ

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

A sex organ (or reproductive organ) is any part of an animal or plant that is involved in sexual reproduction. The reproductive organs together constitute the reproductive system. In animals, the testis in the male, and the ovary in the female, are called the primary sex organs.[1][pages needed] All others are called secondary sex organs, divided between the external sex organs—the genitals or genitalia, visible at birth in both sexes—and the internal sex organs.[1][pages needed]

Mosses, ferns, and some similar plants have gametangia for reproductive organs, which are part of the gametophyte.[2] The flowers of flowering plants produce pollen and egg cells, but the sex organs themselves are inside the gametophytes within the pollen and the ovule.[3] Coniferous plants likewise produce their sexually reproductive structures within the gametophytes contained within the cones and pollen. The cones and pollen are not themselves sexual organs.

Terminology[]

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (August 2021) |

The primary sex organs are the gonads, a pair of sex organs, which diverge into testes following male development or into ovaries following female development. As primary sex organs, gonads generate reproductive gametes containing inheritable DNA. They also produce most of the primary hormones that affect sexual development, and regulate other sexual organs and sexually differentiated behaviors.

Secondary sex organs are the rest of the reproductive system, whether internal or external. The Latin term genitalia, sometimes anglicized as genitals, is used to describe the externally visible sex organs: in male mammals, the penis and scrotum; and in female mammals, the vulva and its organs.

In general zoology, given the great variety in organs, physiologies, and behaviors involved in copulation, male genitalia are more strictly defined as "all male structures that are inserted in the female or that hold her near her gonopore during sperm transfer"; female genitalia are defined as "those parts of the female reproductive tract that make direct contact with male genitalia or male products (sperm, spermatophores) during or immediately after copulation".[4][page needed]

Evolution of sex organs[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (August 2021) |

Evolution of gonads[]

It is hard to find a common origin for gonads but, gonads most likely independently several times.[5] At first testes and ovaries evolved due to natural selection.[6]

Evolution of genitalia[]

A consensus has emerged that sexual selection represents a primary factor for genital evolution.[7] Male genitalia show traits of divergent evolution that are driven by sexual selection.[8]

Animals[]

Mammals[]

External and internal organs[]

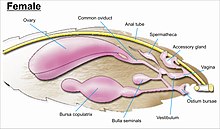

The visible portion of the mammalian genitals for males consists of the scrotum and penis; for females, it consists of the vulva (labia, clitoris, etc.) and vagina.

In placental mammals, females have two genital orifices, the vagina and urethra, while males have only one, the urethra.[9] Male and female genitals have many nerve endings, resulting in pleasurable and highly sensitive touch.[10] In most human societies, particularly in conservative ones, exposure of the genitals is considered a public indecency.[11]

In humans, sex organs include:

| Male | Female |

|---|---|

An image of human male external sex organs (shaved pubic hair) |

An image of human female external sex organs (shaved pubic hair) |

Development[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

In typical prenatal development, sex organs originate from a common primordium during early gestation and differentiate into male or female sexes. The SRY gene, usually located on the Y chromosome and encoding the testis determining factor, determines the direction of this differentiation. The absence of it allows the gonads to continue to develop into ovaries.

Thereafter, the development of the internal, and external reproductive organs is determined by hormones produced by certain fetal gonads (ovaries or testes) and the cells' response to them. The initial appearance of the fetal genitalia looks basically feminine: a pair of urogenital folds with a small protuberance in the middle, and the urethra behind the protuberance. If the fetus has testes, and if the testes produce testosterone, and if the cells of the genitals respond to the testosterone, the outer urogenital folds swell and fuse in the midline to produce the scrotum; the protuberance grows larger and straighter to form the penis; the inner urogenital swellings grow, wrap around the penis, and fuse in the midline to form the penile urethra.

Each sex organ in one sex has a homologous counterpart in the other one. In a larger perspective, the whole process of sexual differentiation also includes development of secondary sexual characteristics such as patterns of pubic and facial hair and female breasts that emerge at puberty.

Because of the strong sexual selection affecting the structure and function of genitalia, they form an organ system that evolves rapidly.[12][13][14] A great variety of genital form and function may therefore be found among animals.

Other animals[]

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (August 2021) |

In many other animals a single posterior orifice, called the cloaca, serves as the only opening for the reproductive, digestive, and urinary tracts (if present). All amphibians, birds, reptiles,[15] some fish, and a few mammals (monotremes, tenrecs, golden moles, and marsupial moles) have this orifice, from which they excrete both urine and feces in addition to serving reproductive functions. Excretory systems with analogous purpose in certain invertebrates are also sometimes referred to as cloacae.

Insects[]

The organs concerned with insect mating and the deposition of eggs are known collectively as the external genitalia, although they may be largely internal; their components are very diverse in form.

Slugs and snails[]

The reproductive system of gastropods (slugs and snails) varies greatly from one group to another.

Planaria[]

Planaria are flat worms widely used in biological research. There are sexual and asexual planaria. Sexual planaria are hermaphrodites, possessing both testicles and ovaries. Each planarian transports its excretion to the other planarian, giving and receiving sperm.

Plants[]

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2021) |

In most plant species an individual has both male and female sex organs.[16]

The life cycle of land plants involves alternation of generations between a sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte. The gametophyte produces sperm or egg cells by mitosis. The sporophyte produces spores by meiosis which in turn develop into gametophytes. Any sex organs that are produced by the plant will develop on the gametophyte. The seed plants, which include conifers and flowering plants have small gametophytes that develop inside the pollen grains (male) and the ovule (female).

Flowering plants[]

In flowering plants the flowers contain the sex organs.[17]

Sexual reproduction in flowering plants involves the union of the male and female germ cells, sperm and egg cells respectively. Pollen is produced in stamens, and is carried to the pistil, which has the ovary at its base where fertilization can take place. Within each pollen grain is a male gametophyte which consists of only three cells. In most flowering plants the female gametophyte within the ovule consists of only seven cells. Thus there are no sex organs as such.

Fungi[]

The sex organs in fungi are called gametangia. In some fungi the sex organs are indistinguishable from each other but in other cases male and female sex organs are clearly different.[18]

Similar gametangia that are similar are called isogametangia. While male and female gametangia are called heterogametangia, which occurs in the majority of fungi.[19]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Robert K. (2005). Anatomy and Physiology: Understanding the Human Body. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763748166.

- ^ "Mosses and Ferns". Biology.clc.uc.edu. 16 March 2001. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Flowering Plant Reproduction". Emc.maricopa.edu. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Eberhard, W.G., 1985. Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia. Harvard University Press

- ^ Schmidt-Rhaesa, Andreas (30 August 2007). The Evolution of Organ Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-19-856668-7.

- ^ switze, International Conference on Comparative Physiology 1992 Crans; Bassau, Short & (4 August 1994). The Differences Between the Sexes. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-44878-9.

- ^ Langerhans, R. Brian; Anderson, Christopher M.; Heinen-Kay, Justa L. (6 September 2016). "Causes and Consequences of Genital Evolution". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (4): 741–751. doi:10.1093/icb/icw101. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 27600556.

- ^ Simmons, Leigh W. (2014). "Sexual selection and genital evolution". Austral Entomology. 53 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/aen.12053. ISSN 2052-1758. S2CID 53690631.

- ^ Marvalee H. Wake (1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7.

- ^ Brigitta Olsen (15 November 2009). Daphne's Dance: True Tales in the Evolution of Woman's Sexual Awareness. Brigitta Olsen. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-9842117-0-8.

- ^ Anita Allen (November 2011). Unpopular Privacy: What Must We Hide?. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-19-514137-5.

- ^ Hosken, David J., and Paula Stockley. "Sexual selection and genital evolution." Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19.2 (2004): 87-93.

- ^ Arnqvist, Göran. "Comparative evidence for the evolution of genitalia by sexual selection." Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Nature 393.6687 (1998): 784.

- ^ Schilthuizen, M. 2014. Nature's Nether Regions: What the Sex Lives of Bugs, Birds, and Beasts Tell Us About Evolution, Biodiversity, and Ourselves. Penguin USA

- ^ "Male reproductive behaviour of Naja oxiana (Eichwald, 1831) in captivity, with a case of unilateral hemipenile prolapse". 2018 – via https://www.biotaxa.org/hn/article/view/34541. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Purves, William K.; Sadava, David E.; Orians, Gordon H.; Heller, H. Craig (2001). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2.

- ^ Purves, William K.; Sadava, David E.; Orians, Gordon H.; Heller, H. Craig (2001). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2.

- ^ Heritage, J.; Evans, E. G. V.; Killington, R. A. (26 January 1996). Introductory Microbiology. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-44977-9.

- ^ Manoharachary, C.; Tilak, K. V. B. R.; Mallaiah, K. V.; Kunwar, I. K. (1 May 2016). Mycology and Microbiology (A Textbook for UG and PG Courses). Scientific Publishers. p. 328. ISBN 978-93-86102-13-3.

Further reading[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sexual anatomy. |

| Look up Wikisaurus:genitalia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Leonard, Janet L. and Alex Córdoba-Aguilar (2010). The Evolution of Primary Sexual Characters in Animals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199717033.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Sex organs