Shafiʽi school

| hidePart of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The Shafiʽi (Arabic: شَافِعِي Shāfiʿī, alternative spelling Shafei) madhhab is one of the four major traditional schools of Islamic law in branch of Sunni Islam.[1][2] It was founded by the Arab scholar Muhammad ibn Idris Al-Shafiʽi, a pupil of Malik, in the early 9th century.[3][4] The school rejected "provincial dependence on traditional community practice" as the source of legal precedent, and "argued for the unquestioning acceptance of the Hadith" as "the major basis for legal and religious judgments".[5] The other three schools of Sunni jurisprudence are Hanafi, Maliki and Hanbali.[1][2]

Like the other schools of fiqh, Shafiʽi relies predominantly on the Quran and the hadiths for Sharia.[3][6] Where passages of Quran and hadiths are ambiguous, the school first seeks religious law guidance from ijma – the consensus of Islamic scholars (according to Syafiq Hasyim).[7] If there was no consensus, the Shafiʽi school relies on qiyās (analogical reasoning) next as a source.[5]

The Shafiʽi school was widely followed in the early history of Islam, but the Ottoman Empire favored the Hanafi school when it became the dominant Sunni Muslim power.[6] One of the many differences between the Shafiʽi and Hanafi schools is that the Shafiʽi school does not consider istihsan (judicial discretion by suitably qualified legal scholars) as an acceptable source of religious law because it amounts to "human legislation" of Islamic law.[8][not specific enough to verify]

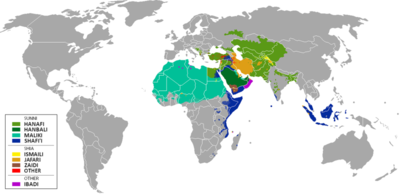

The Shafiʽi school is now predominantly found in Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Lower Egypt, the Swahili coast, Hijaz, Yemen, Kurdistan, The Levant, Dagestan, Chechen and Ingush regions of the Caucasus, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Kerala, Hyderabad Deccan and some other coastal regions in India, Singapore, Myanmar, Thailand, Brunei, and the Philippines.[9]

Principles[]

The Shafiʽi school of thought regards five sources of jurisprudence as having binding authority. In hierarchical order, these are: the Quran, the hadiths—that is, sayings, customs and practices of Muhammad—the ijmā' (consensus of Sahabah, the community of Muhammad's companions),[10] the individual opinions of Sahaba with preference to one closest to the issue as ijtihad, and finally qiyas (analogy).[3] Although al-Shafiʽi's legal methodology rejected custom or local practice as a constitutive source of law, this did not mean that he or his followers denied any elasticity in the Shariah.[11] The Shafiʽi school also rejects two sources of Sharia that are accepted in other major schools of Islam—Istihsan (juristic preference, promoting the interest of Islam) and Istislah (public interest).[12][13] The jurisprudence principle of Istihsan and Istislah admitted religious laws that had no textual basis in either the Quran or Hadiths, but were based on the opinions of Islamic scholars as promoting the interest of Islam and its universalization goals.[14] The Shafiʽi school rejected these two principles, stating that these methods rely on subjective human opinions, and have potential for corruption and adjustment to political context and time.[12][13]

The foundational text for the Shafiʽi school is Al-Risala ("The Message") by the founder of the school, Al-Shafiʽi. It outlines the principles of Shafiʽi fiqh as well as the derived jurisprudence.[15] Al-Risala became an influential book to other Sunni Islam fiqhs as well, as the oldest surviving Arabic work on Islamic legal theory.[16][page needed]

History[]

Imam ash-Shafi'i was reportedly a teacher of the Sunni Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and a student of Imam Malik ibn Anas,[17][18]: 121 who was a student of Ja'far al-Sadiq (a descendant of the Islamic Nabi (Prophet) Muhammad), like Imam Abu Hanifah.[19][20][21] Thus all of the four great Imams of Sunni Fiqh are connected to Imam Ja'far from the Bayt (Household) of Muhammad, whether directly or indirectly.[22]

The Shafiʽi madhhab was spread by Al-Shafiʽi students in Cairo, Mecca and Baghdad. It became widely accepted in early history of Islam. The chief representative of the Iraqi school was Abu Ishaq al-Shirazi, whilst in Khorasan, the Shafiʽi school was spread by al-Juwayni and al-Iraqi. These two branches merged around Ibn al-Salah and his father. The Shafiʽi jurisprudence was adopted as the official law during the Great Seljuq Empire, Zengid dynasty, Ayyubid dynasty and later the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo), where it saw its widest application. It was also adopted by the Kathiri state in Hadhramawt and most of rule of the Sharif of Mecca.[citation needed]

With the establishment and expansion of Ottoman Empire in West Asia and Turkic sultanates in Central and South Asia, Shafiʽi school was replaced with Hanafi school, in part because Hanafites allowed Istihsan (juristic preference) that allowed the rulers flexibility in interpreting the religious law to their administrative preferences.[8] The Sultanates along the littoral regions of the Horn of Africa and the Arabian peninsula adhered to the Shafiʽi school and were the primary drivers of its maritime military expansion into many Asian and East African coastal regions of the Indian Ocean, particularly from the 12th through the 18th century.[23] In the late 19th century, knowledge of Shafiʽi sciences was spread by a network of seagoing sharif merchants.[24]

Demographics[]

The Shafiʽi school is presently predominant in the following parts of the Muslim world:[9]

- Africa: Djibouti, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, lower Egypt and the Swahili Coast.[25]

- Middle East: Hejaz, Yemen, Kurdish regions of the Middle East, and the Levant.

- Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Sri Lanka, (Kerala, southern Tamil Nadu and western Karnataka in) India, Singapore, Myanmar, Thailand, Brunei, and the southern Philippines.

Shafiʽi school is the second largest school of Sunni madhhabs by number of adherents, states Saeed in his 2008 book.[2] However, a UNC publication considers the Maliki school as second largest, and the Hanafi madhhab the largest, with Shafiʽi as third largest.[9] The demographic data by each fiqh, for each nation, is unavailable and the relative demographic size are estimates.

Notable Shafiʽis[]

In Hadith:

|

In Tafsir:

In Fiqh:

In Arabic language studies:

In Aqidah:

|

In Sufism

In history

Statesmen

|

Contemporary Shafiʽi scholars[]

- Abdul Somad

- Abdullah al-Harari

- Sheikh Abubakr Ahmad

- Afifi al-Akiti

- Ahmed Kuftaro

- Ahmad Syafi'i Maarif

- Ali Gomaa

- Habib Umar bin Hafiz

- Habib Ali al-Jifri

- Hasyim Muzadi

- K. Ali Kutty Musliyar

- Kanniyath Ahmed Musliyar

- Mohammad Salim Al-Awa

- Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas

- Nuh Ha Mim Keller

- Shamsul Ulama

- Taha Karaan

- Taha Jabir Alalwani

- Wahba Zuhayli

- Zaid Shakir

- Zainuddin Makhdoom II

- Cherussery Zainuddeen Musliyar

See also[]

- Adhan

- Apostasy in Islam

- Blasphemy in Islam

- Islamic views on sin

- Islamic schools and branches

- Sharia

- Salat

- Wudu

- Madhhab

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hallaq 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Abdullah Saeed (2008), The Qur'an: An Introduction, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415421256, p. 17

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ramadan, Hisham M. (2006). Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary. Rowman Altamira. pp. 27–77. ISBN 978-0-7591-0991-9.

- ^ Kamali 2008, p. 77.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Shāfiʿī ISLAMIC LAW". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shafiʽiyyah Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- ^ Syafiq Hasyim (2005), Understanding Women in Islam: An Indonesian Perspective, Equinox, ISBN 978-9793780191, pp. 75-77

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wael B. Hallaq (2009), Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521861472, pp. 58-71

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jurisprudence and Law - Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- ^ Badr al-Din al-Zarkashi (1393), Al-Bahr Al-Muhit, Vol 6, pp. 209

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 39. ISBN 978-1780744209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Istislah The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press

- ^ Jump up to: a b Istihsan The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press

- ^ Lloyd Ridgeon (2003), Major World Religions: From Their Origins to the Present, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415297967, pp. 259–262

- ^ Majid Khadduri (1961), Islamic Jurisprudence: Shafiʽi's Risala, Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 14–22

- ^ Joseph Lowry (translator), Al-Shafiʽi: The Epistle on Legal Theory, Risalah fi usul al-fiqh, New York University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0814769980

- ^ Dutton, Yasin, The Origins of Islamic Law: The Qurʼan, the Muwaṭṭaʼ and Madinan ʻAmal, p. 16

- ^ Haddad, Gibril F. (2007). The Four Imams and Their Schools. London, the U.K.: Muslim Academic Trust. pp. 121–194.

- ^ "Nafisa at-Tahira". www.sunnah.org.

- ^ Zayn Kassam; Bridget Blomfield (2015), "Remembering Fatima and Zaynab: Gender in Perspective", in Farhad Daftory (ed.), The Shi'i World, I.B Tauris Press

- ^ Aliyah, Zainab (2 February 2015). "Great Women in Islamic History: A Forgotten Legacy". Young Muslim Digest. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Imam Ja'afar as Sadiq". History of Islam. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Allan Christelow (2000), "Islamic Law in Africa," in The History of Islam in Africa (Ed: Nehemia Levtzion, Randall Pouwels), Ohio University Press, ISBN 978-0821412978, page 377

- ^ Randall L. Pouwels (2002), Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521523097, page 139

- ^ UNION OF THE COMOROS 2013 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT U.S. State Department (2014), Quote: "The law provides sanctions for any religious practice other than the Sunni Shafiʽi doctrine of Islam and for prosecution of converts from Islam, and bans proselytizing for any religion except Islam."

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78074-420-9.

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-78074-420-9.

References[]

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521678735.

- Kamali, Mohammad Hashim (2008). Shari'ah Law: An Introduction. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1851685653.

- Yahia, Mohyddin (2009). Shafiʽi et les deux sources de la loi islamique, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, ISBN 978-2-503-53181-6

- Rippin, Andrew (2005). Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 90–93. ISBN 0-415-34888-9.

- Calder, Norman, Jawid Mojaddedi, and Andrew Rippin (2003). Classical Islam: A Sourcebook of Religious Literature. London: Routledge. Section 7.1.

- Schacht, Joseph (1950). The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence. Oxford: Oxford University. pp. 16.

- Khadduri, Majid (1987). Islamic Jurisprudence: Shafiʽi's Risala. Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society. pp. 286.

- Abd Majid, Mahmood (2007). Tajdid Fiqh Al-Imam Al-Syafi'i. Seminar pemikiran Tajdid Imam As Shafie 2007.

- al-Shafiʽi, Muhammad b. Idris, "The Book of the Amalgamation of Knowledge" translated by A.Y. Musa in Hadith as Scripture: Discussions on The Authority Of Prophetic Traditions in Islam, New York: Palgrave, 2008

Further reading[]

- Joseph Lowry (translator), Al-Shafiʽi: The Epistle on Legal Theory (Risalah fi usul al-fiqh), New York University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0814769980.

- Cilardo, Agostino, "Shafiʽi Fiqh", in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014. ISBN 1610691776.

External links[]

- Shafiʽiyyah Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- Al-Shafiʽi Risala Majid Khadduri (Translator), 1961

- Music and Its Effects Ahmed Sheriff, Tanzania, "Why it was forbidden?", pp. 50–55

- Shafi'i

- Madhhab

- Sunni Islamic branches

- Schools of Sunni jurisprudence

- Sunni Islam