Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury

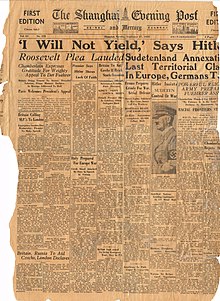

Frontpage of The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury (September 27, 1938) | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | Post-Mercury Co. |

| Founder(s) | Carl Crow |

| Founded | 1929 |

| Ceased publication | 1949 |

The Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury was an English language newspaper in Shanghai, China, published by the Post-Mercury Co. The newspaper represented the point of view of Shanghai's American business community.[1] The newspaper offices were located across from the Shanghai International Settlement. Life reported that the magazine was "old and respected".[2] Nancy Bernkopf Tucker, author of Patterns in the Dust: Chinese-American Relations and the Recognition Controversy, 1949-1950, said that the newspaper was "conservative".[1] The paper had a Chinese edition, Ta Mei Wan Pao[2] (T: 大美晩報, S: 大美晩报, P: Dàměi Wǎnbào[3]). The newspaper was American-owned,[2] and had been founded by Carl Crow. Randall Chase Gould was the editor.[4] Cornelius Vander Starr was the owner. Until his July 1940 death, Samuel H. Chang was the director of the Post and Ta Mei Wan Pao.[2]

History[]

American expatriates established the English version of the newspaper in 1929.[5] Carl Crow, a newspaper businessperson, was the founder. He edited the newspaper for a period, before selecting Randall Gould, a longtime acquaintance, as an editor; Gould began work for the paper in 1931 and remained with the paper until its end in 1949. Paul French, author of Carl Crow, a Tough Old China Hand: The Life, Times, and Adventures of an American in Shanghai, said that the paper, from the beginning was "strongly pro-Chinese though it looked thoroughly American" and had U.S. content.[4] The Chinese edition, Ta Mei Wan Pao, began publication in 1933.[5] Crow worked for the newspaper for a period and left, with Cornelius V. Starr replacing him as the manager of the paper. Starr believed that Crow was not a good choice for a longer term manager but had been a good choice as the founder of the newspaper.[6] Maochun Yu, the author of The Dragon's War: Allied Operations And the Fate of China, 1937-1947, said that the English version "grew into a respectable and influential newspaper in China" and that the Chinese version was very successful.[5] French said that the paper would "become one of the major sources of news on the fluctuations in the Chinese Republic" while it occupied a "heady and competitive atmosphere".[6]

During World War II[]

French said that the paper "continued to be a major evening paper in Shanghai through to the 1940s."[4] In 1937, after invading Shanghai, the Japanese authorities attempted to close down Ta Mei Wan Pao but were unable to do so because it was American-owned. The Japanese continued to allow the production of the English and Chinese versions.[5] Ralph Shaw, a former British soldier and an employee of the North China Daily News, a competing newspaper, said that it was "a large-circulation evening newspaper" which had an "outspokenly anti-Japanese" editor and publisher, Gould.[4] In 1938 journalist Robin Hyde wrote to stating that the offices of the Post had been bombed on two occasions; she said that the Japanese had used bombings of newspaper offices as a method of "newspaper terrorism".[7] In July 1940 the Japanese authorities in Shanghai killed Samuel H. Chang and ordered Starr and Gould to leave China. Starr remained for four additional months before leaving China, with plans to return. Gould remained in China, defying the Japanese order.[2] On December 8, 1941, the Japanese authorities moved into the foreign settlements and forced the English and Chinese papers to close. At that time the Ta Mei Wan Pao had a circulation of 40,000.[5]

In December 1942 Starr asked the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to use his newspaper as a form of conducting morale operations against the Japanese and as intelligence gathering. The OSS accepted Starr's offer on January 1, 1943 and, as a way of gathering intelligence, established a new New York City edition of the newspaper. Gould resumed publication from Chongqing on October 31, 1943, and resumed in Shanghai in August 1945 after the Japanese surrender.[8] The OSS had spent $350,000 ($5.1 million in today's currency) on the editions by July 1944, 18 months after the start of the New York edition. New York and Chongqing editions remained as intelligence projects until the end of World War II. By that month the paper had composed 1,500 papers on various intelligence reports and analysis and an edited information catalog of over 5,000 people of various backgrounds.[5] Yu said that a senior intelligence officer of the OSS explained "Newspapermen everywhere are expected to stick their noses into everybody's business" and therefore their targets do not grow suspicious of their curiosity, so a newspaper business would be "automatically almost indestructible cover for the collection of information."[5]

During the Communist takeover[]

In 1949 Gould voiced support for the Communist Party of China because he had grown tired of Kuomintang rule and believed that improvement to the situation would result from any change from the KMT status quo. Nancy Bernkopf Tucker, author of Patterns in the Dust: Chinese-American Relations and the Recognition Controversy, 1949-1950, said "If conscience prevented de jure recognition of the CCP, he argued that business affairs dictated dealing with the authorities of an ever larger part of China on a de facto basis."[1] After the CCP took power, Gould criticized certain conditions in a manner described by Tucker as "blunt".[1] In June 1949 Gould criticized CCP policies and labor strikes. In response, the printers of the newspaper halted publication and engaged in lock-ins and other disputes. Gould closed the newspaper as a response.[1] Gould said that this incident and other similar incidents "temporarily shattered the relative calm of America's commercial enclaves in China."[1]

Contents[]

The paper included columns from about six news syndicates, crossword puzzles, Dorothy Dix material, and Ripley's Believe It or Not.[4]

See also[]

- Shen Bao

- North China Daily News

- Der Ostasiatische Lloyd

- Shanghai Jewish Chronicle

- Deutsche Shanghai Zeitung

Notes[]

- ^ a b c d e f Tucker, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e "Where U. S. newsmen block the road of Japanese ambition," p. 111.

- ^ Yu, Maochun. "The Role of Media in China During World War II." (Archive) The Institute of 20th Century Media (20世紀メディア研究所), Waseda University. November 22 (year unspecified). Retrieved on November 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e French, p. 172

- ^ a b c d e f g Yu, The Dragon's War: Allied Operations And the Fate of China, 1937-1947, p. 160.

- ^ a b French, p. 174.

- ^ Hyde, p. 363

- ^ "Selected newspaper-Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury." (Archive). Retrieved on August 20, 2020.

References[]

- French, Paul. Carl Crow, a Tough Old China Hand: The Life, Times, and Adventures of an American in Shanghai. Hong Kong University Press, February 15, 2007. ISBN 9622098029, 9789622098022.

- Hyde, Robin. Introduced and selected by Gillian Boddy and Jacqueline Matthews. Disputed Ground: Robin Hyde, Journalist. Victoria University Press, 1991. ISBN 086473204X, 9780864732040.

- Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf. Patterns in the Dust: Chinese-American Relations and the Recognition Controversy, 1949-1950. Columbia University Press, 1983. ISBN 0231053622, 9780231053624.

- "Where U. S. newsmen block the road of Japanese ambition." Life. Time Inc., October 21, 1940. Volume 9, Number 17. ISSN 0024-3019.

- Yu, Maochun. The Dragon's War: Allied Operations And the Fate of China, 1937-1947. Naval Institute Press, August 21, 2006. ISBN 1591149460, 9781591149460.

External links[]

- The Starr Foundation

- Biography of Cornelius Vander Starr, hosted by The Starr Foundation. (Archive)

- "Shanghai under fire" (1938). Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury. Internet Archive

- Shanghai Bombing Incident, 1932: Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury articles. University of Southern California Digital Library.

- The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury. (New York Edition) Worldcat. 1943-1946.

- "標題:日米会談の楽観筋報道 濠洲英語放送十一月二十五日 大美晩報英語放送十一・・" - No. 84 (全 535 件) [画像数:2] - Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, National Archives of Japan. In DJVu and JPEG forms

- American diaspora in Asia

- Publications established in 1929

- 1929 establishments in China

- English-language newspapers published in China

- Newspapers published in Shanghai

- Defunct newspapers published in China

- Shanghai International Settlement

- 1949 disestablishments in China

- Publications disestablished in 1949