Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

View from Fifth Avenue | |

| |

| Established | 1937 |

|---|---|

| Location | 1071 Fifth Avenue at 89th Street Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°46′59″N 73°57′32″W / 40.78306°N 73.95889°WCoordinates: 40°46′59″N 73°57′32″W / 40.78306°N 73.95889°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 953,925 (2016)[1] |

| Director | Richard Armstrong |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: M1, M2, M3, M4, M86 SBS |

| Website | www |

| Built | 1959 |

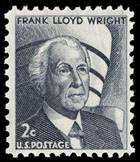

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style(s) | Modern |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-008 |

| State Party | United States |

| Region | Europe and North America |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Designated | May 19, 2005[2] |

| Reference no. | 05000443[2] |

| Designated | October 6, 2008[3] |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | August 14, 1990[4][5] |

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum located at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street in the Upper East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously expanding collection of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, early Modern, and contemporary art and also features special exhibitions throughout the year. The museum was established by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in 1939 as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, under the guidance of its first director, Hilla von Rebay. It adopted its current name in 1952, three years after the death of its founder Solomon R. Guggenheim.

In 1959, the museum moved from rented space to its current building, a landmark work of 20th-century architecture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The cylindrical building, wider at the top than at the bottom, was conceived as a "temple of the spirit". Its unique ramp gallery extends up from ground level in a long, continuous spiral along the outer edges of the building to end just under the ceiling skylight. The building underwent extensive expansion and renovations in 1992 when an adjoining tower was built, and from 2005 to 2008.

The museum's collection has grown over eight decades and is founded upon several important private collections, beginning with that of Solomon R. Guggenheim. The collection is shared with sister museums in Bilbao, Spain and elsewhere. In 2013, nearly 1.2 million people visited the museum, and it hosted the most popular exhibition in New York City.[6]

History[]

Early years and Hilla Rebay[]

Solomon R. Guggenheim, a member of a wealthy mining family, had been collecting works of the old masters since the 1890s. In 1926, he met artist Hilla von Rebay,[7] who introduced him to European avant-garde art, in particular abstract art that she felt had a spiritual and utopian aspect (non-objective art).[7] Guggenheim completely changed his collecting strategy, turning to the work of Wassily Kandinsky, among others. He began to display his collection to the public at his apartment in the Plaza Hotel in New York City.[7][8] As the collection grew, he established the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, in 1937, to foster the appreciation of modern art.[8]

The Museum of Non-Objective Painting[]

The foundation's first venue for the display of art, the "Museum of Non-Objective Painting", opened in 1939 under the direction of Rebay, in midtown Manhattan.[9] Under Rebay's guidance, Guggenheim sought to include in the collection the most important examples of non-objective art available at the time by early modernists such as Rudolf Bauer, Rebay, Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso.[7][8][10]

By the early 1940s, the foundation had accumulated such a large collection of avant-garde paintings that the need for a permanent museum building had become apparent.[11] In 1943, Rebay and Guggenheim wrote a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright asking him to design a structure to house and display the collection.[12] Wright accepted the opportunity to experiment with his organic style in an urban setting. It took him 15 years, 700 sketches, and six sets of working drawings to create the museum.[13]

In 1948, the collection was greatly expanded through the purchase of art dealer Karl Nierendorf's estate of some 730 objects, notably German expressionist paintings.[10] By that time, the foundation's collection included a broad spectrum of expressionist and surrealist works, including paintings by Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Joan Miró.[10][14] After Guggenheim's death in 1949, members of the Guggenheim family who sat on the foundation's board of directors had personal and philosophical differences with Rebay, and in 1952 she resigned as director of the museum.[15] Nevertheless, she left a portion of her personal collection to the foundation in her will, including works by Kandinsky, Klee, Alexander Calder, Albert Gleizes, Mondrian and Kurt Schwitters.[14] The museum was renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1952.[15]

Design[]

Rebay conceived of the space as a "temple of the spirit" that would facilitate a new way of looking at the modern pieces in the collection. She wrote to Wright that "each of these great masterpieces should be organized into space, and only you ... would test the possibilities to do so. ... I want a temple of spirit, a monument!"[16][17] The critic Paul Goldberger later wrote that, before Wright's modernist building, "there were only two common models for museum design: Beaux-arts Palace ... and the International Style Pavilion."[18] Goldberger thought the building a catalyst for change, making it "socially and culturally acceptable for an architect to design a highly expressive, intensely personal museum. In this sense almost every museum of our time is a child of the Guggenheim."[18]

From 1943 to early 1944, Wright produced four different sketches for the initial design. While one of the plans (scheme C) had a hexagonal shape and level floors for the galleries, all the others had circular schemes and used a ramp continuing around the building. He had experimented with the ramp design in 1948 at the V. C. Morris Gift Shop in San Francisco and on the house he completed for his son in 1952, the David and Gladys Wright House in Arizona.[19] Wright's original concept was called an inverted "ziggurat", because it resembled the steep steps on the ziggurats built in ancient Mesopotamia.[20] His design dispensed with the conventional approach to museum layout, in which visitors are led through a series of interconnected rooms and forced to retrace their steps when exiting.[21] Wright's plan was for the museum guests to ride to the top of the building by elevator, to descend at a leisurely pace along the gentle slope of the continuous ramp, and to view the atrium of the building as the last work of art. The open rotunda afforded viewers the unique possibility of seeing several bays of work on different levels simultaneously and even to interact with guests on other levels.[22]

At the same time, before settling on the site for the museum at the corner of 89th Street and the Museum Mile section of Fifth Avenue, overlooking Central Park, Wright, Rebay and Guggenheim considered numerous locations in Manhattan, as well as in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, overlooking the Hudson River.[23] Guggenheim felt that the site's proximity to Central Park was important; the park afforded relief from the noise, congestion and concrete of the city.[20] Nature also provided the museum with inspiration.[23] The building embodies Wright's attempts "to render the inherent plasticity of organic forms in architecture".[21] The Guggenheim was to be the only museum designed by Wright. The city location required Wright to design the building in a vertical rather than a horizontal form, far different from his earlier, rural works.[20][24]

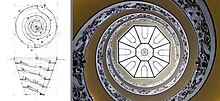

The spiral design recalled a nautilus shell, with continuous spaces flowing freely one into another.[25] Even as it embraced nature, Wright's design also expresses his take on modernist architecture's rigid geometry.[25] Wright ascribed a symbolic meaning to the building's shapes. He explained, "these geometric forms suggest certain human ideas, moods, sentiments – as for instance: the circle, infinity; the triangle, structural unity; the spiral, organic progress; the square, integrity."[26] Forms echo one another throughout: oval-shaped columns, for example, reiterate the geometry of the fountain. Circularity is the leitmotif, from the rotunda to the inlaid design of the terrazzo floors.[23] Several architecture professors have speculated that the double spiral staircase designed by Giuseppe Momo in 1932 at the Vatican Museums was an inspiration for Wright's ramp and atrium.[27][28][29] Jaroslav Josef Polívka assisted Wright with the structural design and managed to design the gallery ramp without perimeter columns.[30]

The Guggenheim's surface was made out of concrete to reduce the cost, inferior to the stone finish that Wright had wanted.[31] Wright proposed a red-colored exterior, which was never realized.[32] The small rotunda (or "Monitor building", as Wright called it) next to the large rotunda was intended to house apartments for Rebay and Guggenheim but instead became offices and storage space.[33] In 1965, the second floor of the Monitor building was renovated to display the museum's growing permanent collection, and with the restoration of the museum in 1990–92, it was turned over entirely to exhibition space and christened the Thannhauser Building, in honor of one of the most important bequests to the museum.[34] Wright's original plan for an adjoining tower, artists' studios and apartments went unrealized, largely for financial reasons, until the renovation and expansion.[22][35] Also in the original construction, the main gallery skylight had been covered, which compromised Wright's carefully articulated lighting effects. This changed in 1992 when the skylight was restored to its original design.[31]

Sweeney years and completion of construction[]

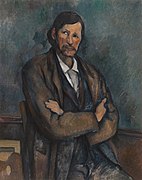

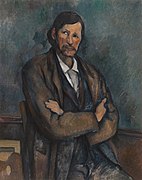

In 1953, the foundation's collecting criteria expanded under its new director, James Johnson Sweeney. Sweeney rejected Rebay's dismissal of "objective" painting and sculpture, and he soon acquired Constantin Brâncuși's Adam and Eve (1921), followed by works of other modernist sculptors, including Joseph Csaky, Jean Arp, Calder, Alberto Giacometti and David Smith.[10] Sweeney reached beyond the 20th century to acquire Paul Cézanne's Man with Crossed Arms (c. 1899).[10] The same year, the foundation also received a gift of 28 important works from the Estate of Katherine S. Dreier, a founder of America's first collection to be called a modern art museum, the Société Anonyme. Dreier had been a colleague of Rebay's. The works included Little French Girl (1914–18) by Brâncuși, an untitled still life (1916) by Juan Gris, a bronze sculpture (1919) by Alexander Archipenko and three collages (1919–21) by German Hanoverian Dadaist Schwitters. It also included works by Calder, Marcel Duchamp, El Lissitzky and Mondrian.[14] Among others, Sweeney also acquired the works of Alberto Giacometti, David Hayes, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.[36]

Sweeney oversaw the last half dozen years of the construction of the museum building, during which time he had an antagonistic relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright, especially regarding the building's lighting issues.[37][38] The distinctive cylindrical building turned out to be Wright's last major work, as the architect died six months before its opening.[39] From the street, the building looks like a white ribbon curled into a cylindrical stack, wider at the top than the bottom, displaying nearly all curved surfaces. Its appearance is in sharp contrast to the typically rectangular Manhattan buildings that surround it, a fact relished by Wright, who claimed that his museum would make the nearby Metropolitan Museum of Art "look like a Protestant barn".[39] Internally, the viewing gallery forms a helical spiral ramp climbing gently from ground level to the skylight at the top.[39]

Critique and opening of the building[]

Even before it opened, the design polarized architecture critics.[39][40] Some believed that the building would overshadow the museum's artworks.[41][42] "On the contrary", wrote the architect, the design makes "the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the World of Art before."[41] Other critics, and many artists, felt that it is awkward to properly hang paintings in the shallow, windowless, concave exhibition niches that surround the central spiral.[39] Prior to the opening of the museum twenty-one artists signed a letter protesting the display of their work in such a space.[39] Historian Lewis Mumford summed up the opprobrium:

Wright has allotted the paintings and sculptures on view only as much space as would not infringe upon his abstract composition. ... [He] created a shell whose form has no relation to its function and offered no possibility of future departure from his rigid preconceptions. [The promenade] has, for a museum, a low ceiling – nine feet eight inches [295 cm] [limiting painting size. The wall] slanted outward, following the outward slant of the exterior wall, and paintings were not supposed to be hung vertically or shown in their true plane but were to be tilted back against it. ... Nor [can a visitor] escape the light shining in his eyes from the narrow slots in the wall.[43]

On October 21, 1959, ten years after the death of Solomon Guggenheim and six months after the death of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Museum first opened its doors to large crowds.[44][11] The building became widely praised[45][46][47] and inspired many other architects.[20]

Messer years[]

Thomas M. Messer succeeded Sweeney as director of the museum (but not the foundation) in 1961 and stayed for 27 years, the longest tenure of any of the city's major arts institutions' directors.[48] When Messer took over, the museum's ability to present art at all was still in doubt due to the challenges presented by continuous spiral ramp gallery that is both tilted and has non-vertical curved walls.[49] It is difficult to properly hang paintings in the shallow, windowless exhibition niches that surround the central spiral: canvasses must be mounted raised from the wall's surface. Paintings hung slanted back would appear "as on the artist's easel". There is limited space within the niches for sculpture.[39]

Almost immediately, in 1962, Messer took a risk putting on a large exhibition that combined the Guggenheim's paintings with sculptures on loan from the Hirshhorn collection.[49] Three-dimensional sculpture, in particular, raised "the problem of installing such a show in a museum bearing so close a resemblance to the circular geography of hell", where any vertical object appears tilted in a "drunken lurch" because the slope of the floor and the curvature of the walls could combine to produce vexing optical illusions.[50] It turned out that the combination could work well in the Guggenheim's space, but, Messer recalled that at the time, "I was scared. I half felt that this would be my last exhibition."[49] Messer had the foresight to prepare by staging a smaller sculpture exhibition the previous year, in which he discovered how to compensate for the space's weird geometry by constructing special plinths at a particular angle, so the pieces were not at a true vertical yet appeared to be so.[50] In the earlier sculpture show, this trick proved impossible for one piece, an Alexander Calder mobile whose wire inevitably hung at a true plumb vertical, "suggesting hallucination" in the disorienting context of the tilted floor.[50]

The next year, Messer acquired a private collection from art dealer Justin K. Thannhauser for the museum's permanent collection.[51] These 73 works include Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and French modern masterpieces, including important works by Paul Gauguin, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Vincent van Gogh and 32 works by Pablo Picasso.[14][52] "Works and Process" is a series of performances at the Guggenheim begun in 1984.[53] The first season consisted of Philip Glass with Christopher Keene on Akhnaten and Steve Reich and Michael Tilson Thomas on The Desert Music.

Krens and expansion[]

Thomas Krens, director of the foundation from 1988 to 2008, led a rapid expansion of the museum's collections.[54] In 1991, he broadened its holdings by acquiring the Panza Collection. Assembled by Count Giuseppe di Biumo and his wife, Giovanna, the Panza Collection includes examples of minimalist sculptures by Carl Andre, Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, and minimalist paintings by Robert Mangold, Brice Marden and Robert Ryman, as well as an array of postminimal, conceptual, and perceptual art by Robert Morris, Richard Serra, James Turrell, Lawrence Weiner and others, notably American examples of the 1960s and 1970s.[14][55] In 1992, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation gifted 200 of his best photographs to the foundation. The works spanned his entire output, from his early collages, Polaroids, portraits of celebrities, self-portraits, male and female nudes, flowers and statues. It also featured mixed-media constructions and included his well-known 1998 Self-Portrait. The acquisition initiated the foundation's photography exhibition program.[14]

Also in 1992, the New York museum building's exhibition and other space was expanded by the addition of an adjoining rectangular tower that stands behind, and taller than, the original spiral, and a renovation of the original building.[35] The new tower was designed by the architectural firm of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects,[56] who analyzed Wright's original sketches when they designed the 10-story limestone tower, which replaced a much smaller structure. It has four additional exhibition galleries with flat walls that are "more appropriate for the display of art".[22][35] In the original construction of the building, the main gallery skylight had been covered, which compromised Wright's carefully articulated lighting effects. This changed in 1992 when the skylight was restored to its original design.[31]

To finance these moves, controversially, the foundation sold works by Kandinsky, Chagall and Modigliani to raise $47 million, drawing considerable criticism for trading masters for "trendy" latecomers. In The New York Times, critic Michael Kimmelman wrote that the sales "stretched the accepted rules of deaccessioning further than many American institutions have been willing to do."[31][57] Krens defended the action as consistent with the museum's principles, including expanding its international collection and building its "postwar collection to the strength of our pre-war holdings"[55] and pointed out that such sales are a regular practice by museums.[57] At the same time, he moved to expand the foundation's international presence by opening museums abroad.[58] Krens was also criticized for his businesslike style and perceived populism and commercialization.[59][60] One writer commented, "Krens has been both praised and vilified for turning what was once a small New York institution into a worldwide brand, creating the first truly multinational arts institution. ... Krens transformed the Guggenheim into one of the best-known brand name in the arts."[61]

Under Krens, the museum mounted some of its most popular exhibitions: "Africa: The Art of a Continent" in 1996; "China: 5,000 Years" in 1998, "Brazil: Body & Soul" in 2001; and "The Aztec Empire" in 2004.[62] It has shown unusual exhibitions on occasion, for example commercial art installations of motorcycles. The New Criterion's Hilton Kramer condemned "The Art of the Motorcycle"[59][63] A 2009 retrospective of Frank Lloyd Wright showcased the architect on the 50th anniversary of the opening of the building and was the museum's most popular exhibit since it began keeping such attendance records in 1992.[64]

In 2001, the museum opened the Sackler Center for Arts Education. The 8,200 square feet (760 m2) facility provides classes and lectures about the visual and performing arts and opportunities to interact with the museum's collections and special exhibitions through its labs, exhibition spaces, conference rooms and 266-seat Peter B. Lewis Theater.[65][66] It is located on the lower level of the museum, below the large rotunda and was a gift of the Mortimer D. Sackler family.[67] Also in 2001, the foundation received a gift of the large collection of the Bohen Foundation, which, for two decades, commissioned new works of art with an emphasis on film, video, photography and new media. Artists included in the collection are Pierre Huyghe and Sophie Calle.[7]

Exterior restoration[]

Between September 2005 and July 2008, the Guggenheim Museum underwent a significant exterior restoration to repair cracks and[68] modernize systems and exterior details.[69] In the first phase of this project, a team of restoration architects, structural engineers, and architectural conservators worked together to create a comprehensive assessment of the building's condition that determined the structure to be fundamentally sound. This initial condition assessment included:

- the removal of paint from the original surface, revealing hundreds of cracks caused over the years, primarily by seasonal temperature fluctuations;[68]

- detailed monitoring of the movement of selected cracks over 17 months;

- impact-echo technology, in which sound waves are sent into the concrete and the rebound is measured to locate voids within the walls;

- laser surveys of the exterior and interior surfaces, believed to be the largest laser model ever compiled;

- core drilling to gather samples of the original concrete and other construction materials; and

- testing of potential repair materials.[70]

Much of the interior of the building was restored during the 1992 renovation and addition by Gwathmey Siegel and Associates Architects. The 2005–2008 restoration primarily addressed the exterior of the original building and the infrastructure. This included the skylights, windows, doors, concrete and gunite facades and exterior sidewalk, as well as the climate-control. The goal was to preserve as much significant historical fabric of the museum as possible, while accomplishing necessary repairs and attaining a suitable environment for the building's continuing use as a museum.[71]

On September 22, 2008, the Guggenheim celebrated the completion of a three-year restoration project. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg officiated at the celebration that culminated with the premiere of artist Jenny Holzer's tribute For the Guggenheim,[72] a work commissioned in honor of Peter B. Lewis, who was a major benefactor in the Museum restoration project. Other supporters of the $29 million restoration included the Board of Trustees of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, and the city's Department of Cultural Affairs. Additional support was provided by the State of New York and MAPEI Corporation.[73]

Recent years[]

In 2005, Krens won a dispute with billionaire philanthropist Peter B. Lewis, chairman of the foundation's Board of Directors and the largest contributor to the foundation in its history. Lewis resigned from the Board, expressing opposition to Krens' plans for further global expansion of the Guggenheim museums.[74] Also in 2005, Lisa Dennison, a longtime Guggenheim curator, was appointed director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Dennison resigned in July 2007, to work at the auction house Sotheby's.[75] Tensions between Krens and the Board continued, and in February 2008 Krens stepped down as the Director of the foundation, although he remains an advisor for international affairs.[76]

Richard Armstrong became the fifth director of the museum on November 4, 2008. He had been director of the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for 12 years, where he had also served as chief curator and curator of contemporary art.[77] The chief curator and deputy director of the museum is Nancy Spector.[78]

In addition to its permanent collections, which continue to grow,[7] the foundation administers loan exhibitions and co-organizes exhibitions with other museums to foster public outreach.[79] In 2013, nearly 1.2 million people visited the museum, and its James Turrell exhibition was the most popular in New York City in terms of daily attendance.[6]

In 2019, Chaédria LaBouvier became the first black woman curator to create a solo exhibition and first black person to write a text published by the museum.[80][81] She accused the museum of racism after it refused to let her contribute to the audio guide for her exhibition and allegedly withheld resources from her and excluded her from a panel hosted about the show. Within a month after LaBouvier made these criticisms, the museum hired its first full-time black curator, Ashley James.[82]

Landmark designations[]

On August 14, 1990, the museum and its interior were separately designated as New York City Landmarks.[4][5] The museum was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 19, 2005,[2] and was registered as a National Historic Landmark on October 6, 2008.[3] In July 2019, the Guggenheim was among eight properties by Wright placed on the World Heritage List under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright".[83][84][85]

Selected works in the collection[]

Paul Cézanne, c.1899, Homme aux bras croisés (Man With Crossed Arms), oil on canvas, 92 x 72.7 cm

Georges Braque, 1909, Violin and Palette (Violon et palette, Dans l'atelier), oil on canvas, 91.7 x 42.8 cm

Wassily Kandinsky, 1910, Landscape with Factory Chimney, oil on canvas, 66.2 x 82 cm

Franz Marc, 1911, The Yellow Cow, oil on canvas, 140.5 x 189.2 cm

Juan Gris, 1911, Maisons à Paris (Houses in Paris), 1911, oil on canvas, 52.4 x 34.2 cm

Fernand Léger, 1911–12, Les Fumeurs (The Smokers), oil on canvas, 129.2 x 96.5 cm

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), oil on canvas, 90.7 x 64.2 cm

Fernand Léger, 1912–13, Nude Model in the Studio (Le modèle nu dans l'atelier), oil on burlap, 128.6 x 95.9 cm

Alexander Archipenko, 1913, Pierrot-carrousel, painted plaster, 61 × 48.6 × 34 cm

Marc Chagall, 1913, Paris par la fenêtre (Paris Through the Window), oil on canvas, 136 x 141.9 cm

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1914 (cast c.1930), Le cheval (The Horse), bronze, 43.6 × 41 cm

Albert Gleizes, 1914–15, Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portrait d'un médecin militaire), oil on canvas, 119.8 x 95.1 cm

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1915, The soldier bath or Artillerymen, oil on canvas, 140.3 × 151.8 cm

Albert Gleizes, 1915, Brooklyn Bridge (Pont de Brooklyn), oil and gouache on canvas, 102 x 102 cm cm

Juan Gris, 1917, Compotier et nappe à carreaux (Fruit Dish on a Checkered Tablecloth), oil on wood panel, 80.6 x 53.9 cm

Amedeo Modigliani, 1917, Nude (Nu), oil on canvas, 73 × 116.7 cm

Theo van Doesburg, 1918, Composition XI, oil on canvas, 57 x 101 cm

Paul Klee, 1922, Red Balloon (Roter Ballon) oil on chalk-primed gauze, mounted on board, 31.7 × 31.1 cm

See also[]

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of Guggenheim Museums

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ "Visitor figures 2016" (PDF). The Art Newspaper. April 2017. p. 14. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "National Register of Historic Places; New Listings October 6 – October 10, 2008", NPS.gov, October 17, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 14, 1990. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum: Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 14, 1990. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Top 100 Art Museum Attendance", The Art Newspaper, 2014, pp. 11 and 15, accessed July 8, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Exhibition of Works Reflecting the Evolution of the Guggenheim's Collection Opens in Bilbao", artdaily.org, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Biography: Solomon R. Guggenheim", Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Vail 2009, pp. 25, 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Calnek, Anthony, et al. The Guggenheim Collection, pp. 39–40, New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2006

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Guggenheim Foundation History". Guggenheim. February 29, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Vail 2009, p. 333.

- ^ "Guggenheim Architecture". Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Guggenheim Museum New York", Encyclopedia of Art, visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Biography: Hilla Rebay", Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Levine 1996, p. 299.

- ^ The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of the Modern Museum, pp. 217–18, New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Secret Life of Buildings: New York Public Library and Guggenheim Museum"[permanent dead link], Colebrook Bosson Saunders Products Ltd.. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1981). Arquitectura de los siglos XIX y XX (6th ed.). Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra. p. 477. ISBN 9788437624464.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Storrer 2002, pp. 400–01

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1996, p. 340.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Perez, Adelyn. "AD Classics: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum", May 18, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ballon 2009, pp. 22–27

- ^ Since Wright was not licensed as an architect in New York, he relied on Arthur Cort Holden, of the architectural firm Holden, McLaughlin & Associates, to deal with New York City's Board of Standards and Appeals. Dal Co, Francesco (2017). The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright's Iconoclastic Masterpiece. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0300226058. OCLC 969981835.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1996, p. 301.

- ^ Rudenstine, Angelica Zander. The Guggenheim Museum Collection: Paintings, 1880–1945, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1976, p. 204

- ^ Tanzj, Daniela; Bentivegna, Andrea (July 23, 2015). "The Vatican Museums and the Guggenheim: Two Ingenious Spirals of Art". La Voce di New York.

- ^ Hersey, George L. (1993). High Renaissance art in St. Peter's and the Vatican: an interpretative guide. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780226327822.

- ^ Mindel, Lee F. (February 28, 2013). "Compares the Oculi at the Vatican and the Guggenheim Museum". Architectural Digest.

- ^ Jaroslav J. Polívka, "What it's Like to Work with Wright" in Tejada, Susana, ed. (2000). Engineering the Organic: The Partnership of Jaroslav J. Polivka and Frank Lloyd Wright. Buffalo: State University of New York. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sennott 2004, pp. 572–73

- ^ Bianchini, Riccardo. "The Guggenheim, an American revolution", inexhibit.com, 2014, accessed July 5, 2014.

- ^ Levine 1996, p. 317.

- ^ Ballon 2009, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Overview of firm's history, projects, etc. Gwathmey Siegel website

- ^ The Global Guggenheim, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Publications. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ "James Johnson Sweeney records", Solomon R. Guggenheim Archives Collections. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Glueck, Grace. "James Johnson Sweeney Dies; Art Critic and Museum Head". The New York Times. April 15, 1986.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Art: Last Monument". Time. November 2, 1959.

- ^ "Controversial Museum Opens in New York", The News and Courier, October 22, 1959, p. 9-A.

- ^ Jump up to: a b “Oct 21, 1959: Guggenheim Museum opens in New York City”, This Day in History, History.com. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul. "Spiralling Upward", Celebrating fifty years of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim, The New Yorker, May 25, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis "The Sky Line: What Wright Hath Wrought" (1959) in The Highway and the City, New York: New American Library, 1964. pp. 141–142 (first published in The New Yorker, December 5, 1959)

- ^ Spector 2001, p. 16.

- ^ "The Wright Stuff". USA Today (Weekend). November 6, 1998[dead link]

- ^ Levine 1996, p. 362.

- ^ "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum", The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Kumar 2011, chapter: "Thomas Messer".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Russell, John. "Director of Guggenheim Retiring After 27 Years", The New York Times, November 5, 1987. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Canaday, John. "Museum Director Solves Problem; Guggenheim Official Faces Troubles of Architecture", The New York Times, August 17, 1962

- ^ Decker, Andrew. "Oral History Interview with Thomas M. Messer, 1994 Oct. – 1995 Jan.", Archives of American Art, January 25, 1995. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ "Thannhauser, Justin K.: The Frick Collection", Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ "Works & Process". Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Vogel, Carol. "Guggenheim's Provocative Director Steps Down", The New York Times, February 28, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Glueck, Grace. "Guggenheim May Sell Artworks to Pay for a Major New Collection", The New York Times, March 5, 1990. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ Gwathmey Siegel web site: Overview of firm's history, projects, etc.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kimmelman, Michael (April 1, 1990), "Art View; The High Cost of Selling Art", The New York Times, retrieved April 9, 2012

- ^ Russell, James S. "Guggenheim's Krens Eyes Hudson Yards Museum, Seeks New Bilbaos", Bloomberg, March 11, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sudjic, Deyan (January 23, 2005), "Is this the end of the Guggenheim dream?", The Observer, London, UK: Guardian News and Media Limited

- ^ Gibson, Eric (November 27, 1998), "For Museums, Bigger Is Better", The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Mahoney, Sarah (October 2, 2006), "Thomas Krens", Advertising Age, 77 (40), p. I-8

- ^ Vogel, Carol. "A Museum Visionary Envisions More", The New York Times, April 27, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Plagens, Peter (September 7, 1998), "Rumble on the Ramps. ('The Art of the Motorcycle', Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)", Newsweek, 132 (10), p. 80

- ^ "Kandinsky Retrospective Helps Set New Attendance Record for 2009". Guggenheim. January 25, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Sackler Center for Arts Education" Archived February 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Tu, Jeni (February 1, 2002). "Higher education meets high art". Dance Teacher. Archived from the original on September 21, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (March 31, 2010). "Mortimer D. Sackler, Arts Patron, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2014.; "Museum gets gift for arts education". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. New York Times News Service. December 12, 1995. p. 2E. Retrieved August 22, 2014.; and "Kim Kanatani Will Occupy Newly Created Gail Engelberg Chair in Education". The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Archived from the original (Press release) on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Park, Haeyoun. "Face-lift for an Aging Museum", The New York Times, April 16, 2007

- ^ Guggenheim Museum web site: click link to podcast about restoration (10 MB, audio only, 8 min 45 sec)

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin. "The Restorers' Art of the Invisible", The New York Times, September 10, 2007, pp. E1–5.

- ^ Guggenheim Museum web site: click link to podcast about restoration (10 MB, audio only, 8 min 45 sec) Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Villarreal, Ignacio. "Guggenheim Marks Completion of Restoration With First Public Viewing of Work by Artist Jenny Holzer", Artdaily.com. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ Guggenheim Museum web site: press release about restoration Archived June 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vogel, Carol. "Guggenheim Loses Top Donor in Rift on Spending and Vision", January 20, 2005, The New York Times'. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Carol. "Director of Guggenheim Resigns to Join Sotheby's". The New York Times. July 31, 2007.

- ^ Lewis, Carol. "Provocative Guggenheim director resigns", The New York Times, February 28, 2008, accessed October 21, 2011.

- ^ Vogel, Carol. "Guggenheim Chooses a Curator, Not a Showman", The New York Times, September 23, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "25 Art World Women at the Top, From Sheikha Al-Mayassa to Yoko Ono", Artnet, April 17, 2014

- ^ Foundation website's collaborations page Archived April 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mitter, Siddhartha (July 30, 2019). "Behind Basquiat's 'Defacement': Reframing a Tragedy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Chaédria LaBouvier". The Root. 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Greig, Jonathan (November 19, 2019). "Blavity News & Politics". Blavity News & Politics. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Guggenheim museum among eight buildings by Frank Lloyed wright inscribed on UNESCO world heritage list". TeRra Magazine.

- ^ "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Tareen, Sophia (July 8, 2019). "Guggenheim Museum Added to UNESCO World Heritage List". NBC New York. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

Sources[]

- Ballon, Hillary; et al. (2009). The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of the Modern Museum. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Kumar, Lisa (2011). The Writers Directory. Detroit: St. James Press. ISBN 9781558628137.

- Levine, Neil (1996). The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Sennott, R. Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Architecture. 2. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Spector, Nancy, ed. (2001). Guggenheim Museum Collection: A to Z. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

- Storrer, William Allin (2002). The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalogue. Chicago: University of Chicago Press., S.400

- Vail, Karole, ed. (2009). The Museum of Non-Objective Painting. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

External links[]

- Official website

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum at Google Cultural Institute

- Landmarks Preservation Commission Report

- Gwathmey Siegel Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Renovation and Addition project page

- Architectural Review

- New York Academy of Sciences Podcast about Imageless Exhibit

- "Frank Lloyd Wright: The Natural" – slideshow by Life magazine of Wright's work, including several photographs of the Guggenheim

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Art museums in New York City

- Buildings and structures completed in 1959

- Buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Fifth Avenue

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- Guggenheim family

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

- Modern art museums in the United States

- Modernist architecture in New York City

- Museums established in 1937

- Museums in Manhattan

- Museums of American art

- National Historic Landmarks in Manhattan

- Rotundas in the United States

- Upper East Side

- New York City interior landmarks