Songhai proper

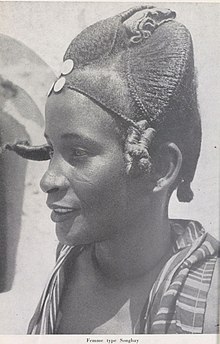

Songhay woman, Niger (1900s) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 2,000,000[1][2] | |

| Languages | |

| Songhoyboro Ciine | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Zarma, Tuareg, Peulh, Hausa | |

The Songhai proper (Songhay, Songhoy, Sonrai, Songway) are an ethnic group in the northwestern corner of Niger's Tillaberi Region, an area historically known in the country as Songhai.[3] They are a subgroup of the broader Songhai group. Even though the Songhays have so much in common with the Zarma people to the extent some Songhais may refer to themselves and their dialect as "Zarma", both see themselves as two different people.[4]

The Songhai originally are the descendants and partisans of the Sonni Dynasty that retreated to this area of present Niger after the coup d'état of 1493[5] and that of the Askia Dynasty that also moved later to this same region after the invasion of the Songhai Empire by the Saadi Dynasty of Morocco in 1591.[6][7][8][9]

Aristocracy[]

According to oral history, the Songhai nobles came to be known as "Songhai" during the reign of Sonni Ali Ber, the name was coined from his name to form a tribal name. So therefore, unlike other Songhai people that identify by different names such as Zarma and Kurtey, this group just go by the name "Songhai" because they are the descendants of the ruling caste of the Songhai Empire from which the empire got its name. They are the descendants of both Songhai noble dynasties (i.e. Sonni Dynasty and Askia Dynasty)

Thus, the Songhai are classified into two groups; the descendants of the Sonnis are known as "Si Hamey"[a] and the descendants of the Askias are known as "Mamar Hamey" ("Mamar" is the vernacular name of Askia Mohammad I). [10][11] It is also worth noting both groups use the title surname "Maiga" (meaning, a King or Prince).[12]

History[]

Sonni/Si Hamey

The Si Hamey are the descendants and partisans of the founder and first emperor of the Songhai Empire, Sonni Ali Ber.

After the ruler and founder of the Songhai Empire Sonni Ali died in 1492, his former army general and nephew Askia Mohammad rebelled against his son and successor, Sonni Baru and defeated him in a battle in 1493 . Sonni Baru fled to Ayorou and established his own small state which was again defeated in 1500 after constant attacks and was incorporated into the Songhai empire.

Mãmar Hamey

The Mamar Hamey are the descendants Askia Mohammad I who is the son of Si/Sonni Ali Ber's sister "Kassey".

After the defeat of the Songhai Empire at the battle of Tondibi in 1591, the son of Askia Dawud , Askia Muhammed Gao (aka Wayki) deposed his brother Askia Ishaq II and briefly took command of the Songhai resistance army. Supported by the remains of the disbanded army, they migrated down river from Gao to the region where the Si Hamey had already taken refuge after their overthrow precisely in the Tillabery Region in present-Niger and had almost assimilated with their Zarma cousins (The Zarma are among the descendants/partisans of the pre-imperial Songhay Za Dynasty who had rebelled against the advent of Islamization and migrated to occupy new lands).

Askia Wayki (Muhammed Gao) installed his base on the banks of the Niger river in the current locality of Sikié hoping in vain for a possible passage of the Moroccan army. Askia Muhammed Gao died in 1632 without being able to regroup his men to reclaim Gao, which had fallen under the control of Judar Pasha. His son, Fari Monzon (Fari Mondyo) who was an Inspector of tax collection during the reign of Askia Ishaq I succeeded him and in 1661 tried for the second time to regroup the Songhai including their rival cousins (the Si Hamey and the Zarma) in order to take back the city of Gao. Together, they were able to garner the support of the Tuaregs from Imanan and Azawad.

Recognizing the strength of the Moroccan army, they later decided to abandon the struggle for the re-establishment of the Songhai Empire. The son of Fari Monzon, Tabari took command of Karma, a principality established since the passage of Askia Mohammad I during his pilgrimage to Mecca. His other brothers and cousins created the kingdoms of Namaro, Gothèye, Dargol, Téra, Sikié, Kokorou and Say.

Historically, when a kingdom is defeated, no prince or noble is allowed to reside in their conquered territory. Either they are exterminated or they flee. This emptied Gao and Timbuktu of its Songhai princes/princesses and other nobles who find themselves today dispersed in the above-mentioned regions (mainly in Southwestern Niger)

This marked the end of the Empire which shone for its immensity and courage of its leaders in spite of multiple incessant internal conflicts of succession. These kingdoms, however, did not find their union circumstantial until March 1906, during the anti-colonial battle of Karma-Boubon led by Oumarou Kambessikonou (Morou Karma) , a descendant of the Askia Daoud and brother to Askia Muhammed Gao.[13][14]

Society and Culture[]

The Songhai proper have traditionally been a socially stratified society, like many West African ethnic groups with castes.[15][16] According to the medieval and colonial era descriptions, their vocation is hereditary, and each stratified group has been endogamous.[17] The social stratification has been unusual in two ways; it embedded slavery, wherein the lowest strata of the population inherited slavery, and the Zima, or priests and Islamic clerics, had to be initiated but did not automatically inherit that profession, making the cleric strata a pseudo-caste.[18]

Louis Dumont, the 20th-century author famous for his classic Homo Hierarchicus, recognized the social stratification among Zarma-Songhai people as well as other ethnic groups in West Africa, but suggested that sociologists should invent a new term for West African social stratification system.[19] Other scholars consider this a bias and isolationist because the West African system shares all elements in Dumont's system, including economic, endogamous, ritual, religious, deemed polluting, segregative and spread over a large region.[19][20][21] According to Anne Haour – a professor of African Studies, some scholars consider the historic caste-like social stratification in Zarma-Songhay people to be a pre-Islam feature while some consider it derived from the Arab influence.[19]

The different strata of the Songhai have included the kings and warriors, the scribes, the artisans, the weavers, the hunters, the fishermen, the leather workers and hairdressers (Wanzam), and the domestic slaves (Horso, Bannye). Each caste reveres its own guardian spirit.[15][19] Some scholars such as John Shoup list these strata in three categories: free (chiefs, farmers and herders), servile (artists, musicians and griots), and the slave class.[22] The servile group were socially required to be endogamous, while the slaves could be emancipated over four generations. The highest social level, states Shoup, claim to have descended from King Sonni 'Ali Ber and their modern era hereditary occupation has been Sohance (sorcery). The traditionally free strata of the Songhai proper and Zarma have owned property and herds, and these have dominated the political system and governments during and after the French colonial rule.[22] Within the stratified social system, the Islamic system of polygynous marriages is a norm, with preferred partners being cross cousins.[23][24] This endogamy within Songhai-Zarma people is similar to other ethnic groups in West Africa.[25]

Livelihood[]

The Songhay are mostly agriculturalists (mostly growing rice and millet), hunters, fishers and cattle owners which they let the Fulani tend.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Hamey (singular; "Hama') means; Descendants

References[]

- ^ "Africa: Niger - The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Niger, retrieved 2021-03-12

- ^ Zarma, a Songhai language, retrieved 2021-02-23

- ^ Stoller, Paul (1992), The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch, p. 59 "In this way the true Songhay, after the seventeenth century,is no longer the one of Timbuktu or Gao, but the one farther south near the Anzourou, the Gorouol, on the islands of the river surrounded by rapids" (Rouch 1953, 224), ISBN 9780226775487, retrieved 2021-06-04

- ^ Idrissa, Abdourahmane; Decalo, Samuel (2012), Historical Dictionary of Niger by Abdourahmane Idrissa, Samuel Decalo, p. 414, ISBN 9780810870901, retrieved 2021-03-17

- ^ Olivier de Sardan, Jean-Pierre (2000), Unité et diversité de l'ensemble songhay-zarma-dendi

- ^ Bernussou, Jérôme (8 June 2020), "Chapitre I. Les nouveaux axes de l'historiographie universitaire : « histoire totale » et « histoire politique », à partir des années 70", HISTOIRE ET MÉMOIRE AU NIGER, Méridiennes, Presses universitaires du Midi, pp. 41–112, ISBN 9782810709519, retrieved 2021-03-30

- ^ Southern Songhay Speech Varieties In Niger:A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Zarma, Songhay, Kurtey, Wogo, and Dendi Peoples of Niger (PDF), Byron & Annette Harrison and Michael J. Rueck Summer Institute of Linguistics B.P. 10151, Niamey, Niger Republic, 1997, retrieved 2021-02-23

- ^ Soumalia, Hammadou; Hamidou, Moussa; Laya, Diouldé (January 1998), Traditions des Songhay de Tera (Niger) by Hammadou Soumalia, Moussa Hamidou, Diouldé Laya, ISBN 9782865378517, retrieved 2021-04-14

- ^ Bornand, Sandra (2012), Is Otherness Represented in Songhay-Zarma society? A case study of the 'Tula' story (PDF), London, United Kingdom., retrieved 2021-04-12

- ^ Bernussou, Jérôme (8 June 2020), "Chapitre I. Les nouveaux axes de l'historiographie universitaire : « histoire totale » et « histoire politique », à partir des années 70", HISTOIRE ET MÉMOIRE AU NIGER, Méridiennes, Presses universitaires du Midi, pp. 41–112, ISBN 9782810709519, retrieved 2021-03-30

- ^ Journal de la Société des africanistes, Volume 36, France: Société des africanistes, 1966, p. 256, retrieved 2021-04-21

- ^ Michel, Jonathan (1995), The Invasion of Morocco in 1591 and the Saadian Dynasty, retrieved 2021-04-17

- ^ Askia Mohammed V Gao, Fr Wiki

- ^ a b Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan (1984). Les sociétés Songhay-Zarma (Niger-Mali): chefs, guerriers, esclaves, paysans. Paris: Karthala. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-2-86537-106-8.

- ^ Tal Tamari (1991). "The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 32 (2): 221–250. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025718. JSTOR 182616., Quote: "[Castes] are found among the Soninke, the various Manding-speaking populations, the Wolof, Tukulor, Senufo, Minianka, Dogon, Songhay, and most Fulani, Moorish and Tuareg populations".

- ^ I. Diawara (1988), Cultures nigériennes et éducation : Domaine Zarma-Songhay et Hausa, Présence Africaine, Nouvelle série, number 148 (4e TRIMESTRE 1988), pages 9-19 (in French)

- ^ Abdourahmane Idrissa; Samuel Decalo (2012). Historical Dictionary of Niger. Scarecrow Press. pp. 474–476. ISBN 978-0-8108-7090-1.

- ^ a b c d Anne Haour (2013). Outsiders and Strangers: An Archaeology of Liminality in West Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–97, 100–101, 90–114. ISBN 978-0-19-969774-8.

- ^ Declan Quigley (2005). The character of kingship. Berg. pp. 20, 49–50, 115–117, 121–134. ISBN 978-1-84520-290-3.

- ^ Bruce S. Hall (2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–18, 71–73, 245–248. ISBN 978-1-139-49908-8.

- ^ a b John A. Shoup (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0.

- ^ Songhai people Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Bonnie G. Smith (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 503–504. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- ^ Tal Tamari (1998), Les castes de l'Afrique occidentale: Artisans et musiciens endogames, Nanterre: Société d’ethnologie, ISBN 978-2901161509 (in French)

- Languages of Niger

- Songhay languages

- Zarma people

- Ethnic groups in Niger

- Muslim communities in Africa