Sonnet 43

| Sonnet 43 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

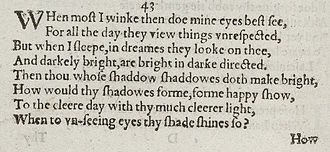

The first two stanzas of Sonnet 43 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 43 employs antithesis and paradox to highlight the speaker's yearning for his beloved and sadness in (most likely) their absence, and confusion about the situation described in the previous three sonnets. Sonnet 27 similarly deals with night, sleep, and dreams.

Structure[]

Sonnet 43 is an English or Shakespeare sonnet. English sonnets contain three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions per line. The first line of the couplet exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / All days are nights to see till I see thee, (43.13)

The second and fourth lines have a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

× / × / × / × / × / (×) And darkly bright, are bright in dark directed. (43.4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Source and analysis[]

This is one of the poems omitted from the pirated edition of 1640. Gerald Massey notes an analogous poem in Philip Sidney's Astrophil and Stella, 38.

Stephen Booth notes the concentration of antithesis used to convey the impression of a speaker whose emotions have inverted his perception of the world.

Edmond Malone glosses "unrespected" as "unregarded." Line 4 has received a number of broadly similar interpretations. Edward Dowden has "darkly bright" as "illumined, though closed"; he glosses the rest of the line "clearly directed in the darkness." Sidney Lee has the line "guided in the dark by the brightness of your shadow," while George Wyndham prefers "In the dark they heed that on which they are fixed."

In line 11, Edward Capell's emendation of the quarto's "their" to "thy" is now almost universally accepted.

Musical settings[]

The sonnet was set to music by Benjamin Britten as the last song of his eight-song cycle Nocturne Op. 60 (1958) for tenor, 7 obbligato instruments (flute, clarinet, cor anglais, bassoon, French horn, timpani, harp) and strings.

In 1990 Dutch composer Jurriaan Andriessen set the poem to a mixed chamber choir setting.

Rufus Wainwright's "Sonnet 43", the sixth track on his album All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu (2010), is a musical setting of the sonnet.

In 2004 the Flemish composer Ludo CLAESEN set this poem to a setting for chambermusic (flute, piano and soprano-solo). An amazing recording as an attachment of the Book-CD "Là-bas" you may find by the Belgian 'l'ensemble de musique Nahandove' edited by Esperluète editions.

A 2007 production by The Public Theater of King Lear in Central Park featured incidental music by Stephen Sondheim and Michael Starobin. It included a setting of Sonnet 43 by Sondheim.

Laura Hawley composed a lively setting of Sonnet 43 for choir in 2013.[2]

The Korean-pop group Enhypen used lines from Sonnet 43 in the song Outro : The Wormhole from their second mini-album "Border: Carnival".

The Korean-pop group Gfriend used lines from Sonnet 43 in the opening sequence of their music video Sunny Summer in 2018.

Notes[]

- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ Laura Hawley's setting of Sonnet 43.

References[]

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Levy, David (4 November 2013). "http://fuckyeahstephensondheim.tumblr.com/post/66015392196/when-the-public-theater-did-king-lear-in-central". Fuck Yeah Stephen Sondheim. Retrieved 8 November 2013

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links[]

- British poems

- Sonnets by William Shakespeare