Sonnet 69

| Sonnet 69 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

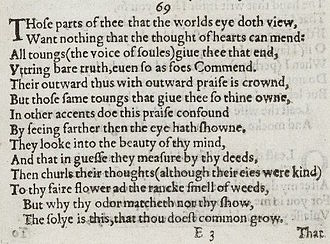

Sonnet 69 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Shakespeare's Sonnet 69, like many of those nearby in the sequence, expresses extremes of feelings about the beloved subject, who is presented as at once superlative in every way and treacherous or disloyal.

Paraphrase[]

What the world can see of you is perfect; no one denies you that name of perfection. Everyone admits this without hesitation or limitation. But the same people who so readily praise your beauty reverse that praise when they examine you in other ways. These people, judging your mind and character by your actions, decide that you are as much foul as beautiful. And the reason that your odor does not match your appearance is you have become common (i.e. keep company that befouls your reputation.)

Structure[]

Sonnet 69 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fifth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Thy outward thus with outward praise is crown'd; (69.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The twelfth line is open to several alternative scansions. It may exhibit two instances of the rightward movement of an ictus (the resulting four-position figure, × × / /, is sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / × × / / × / To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds: (69.12)

(This figure can also be found in the first line.) Alternatively, the line could be scanned with one minor ionic followed by a mid-line reversal (replacing × / with / ×):

× × / / / × × / × / To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds: (69.12)

(An initial reversal is present in line four, and a possible mid-line reversal in line three.) Finally, the first four syllables could be scanned with a regular iambic alternation — followed by either of the above-mentioned placements of the third ictus.

Source and analysis[]

As Stephen Booth notes, the sonnet is carelessly printed, and its emendation history begins with the 1640 quarto. Edmond Malone altered the quarto's "end" (3) to "due," and this change is now commonly accepted as necessary for rhyme. Quarto's "Their" (5) is just as commonly emended to "Thy" on semantic grounds; the change was first proposed by Edward Capell.

The most significant crux is "solye" (14). Malone suggested "solve" while admitting that he could not find other instances of "solve" as a noun, nor have two centuries of subsequent investigation found one. On no less tenuous grounds, George Steevens proposed "sole" as a noun. More common now is the emendation of "soil" in an archaic meaning "to solve." Instances of the word in this meaning have been found in Nicholas Udall's Erasmus and in Hamlet.

George Wyndham was unable to explain the capitalization of "Commend," one of only three such failures in his interpretation.

The poem prefigures the flower language of the more famous Sonnet 94.

See also[]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

Sources[]

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspere's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

- British poems

- Sonnets by William Shakespeare