South Seas

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

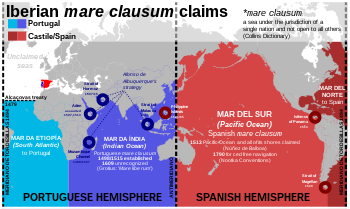

Today the term South Seas, or South Sea, is used in several contexts. Most commonly it refers to the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of the equator.[1] In 1513, when Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa coined the term Mar del Sur, or South Sea, the term was applied to the entire area of today's Pacific Ocean. In 1520 Ferdinand Magellan named the same ocean the Pacific Ocean, and over time Magellan's name became dominant. The South Sea term was retained, but was applied only to southern areas of the Pacific.

The term South Sea may also be used synonymously for Oceania, or even more narrowly for Polynesia or the Polynesian Triangle, an area bounded by the Hawaiian Islands, New Zealand and Easter Island. Pacific Islanders are commonly referred to as South Sea Islanders, particularly in Australia.

Origin[]

The Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa coined the term "South Sea" when he traveled across the Isthmus of Panama and reached the Bay of San Miguel, naming the ocean ahead Mar del Sur ("South Sea") due to its location along the southern shore of the isthmus.[2]

Núñez de Balboa and his soldiers tried to travel to the peak of the mountain to see the huge sea, but when they arrived at the foot of the mountain there were only 69 out of 190 soldiers left. He didn't want to share the experience of being the first to see the unknown ocean so he commanded his crew to stand still and wait. On 25 September 1513, he was the first European to see the Pacific Ocean. After looking at the ocean for some time, he told his crew to come up to share his happiness and his pride with them.[citation needed]

After he set foot into the ocean, at the opening of the Saban river, he declared the South Sea, and all adjoining lands, to be property of his king.[2]

South Sea Paradise[]

In a figurative sense, the South Sea is an often idealized and distant region. An entire genre of literature and film has developed around the romance of the region.

In 1773, when James Cook came to Tahiti for the second time, he was accompanied by two scientifically educated Germans Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster.

- "What a morning - impossible to be described more beautifully by any poet - when we saw the isle O-Taheiti two miles ahead of us."

The report of the discoverers determined the Europeans' picture of the South Sea for a long time. On these grounds, Joseph Banks wrote:

- "An Arcadia of which we will be king."

Louis Antoine de Bougainville's romantic travel report Voyage autour du monde as well as Georg Forster's travel description A Voyage Round the World (1777) confirmed Jean-Jacques Rousseau's image of the "noble savages". He describes the country as "jardin d’Eden" (Garden of Eden), which provided his residents with everything required to live. He saw the islanders as pure humans not yet poisoned by civilization. The report Voyage autour du monde inspired Denis Diderot to write his essay Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, a plea for sexual freedom.

Paul Gauguin, a French artist, contributed to this picture as well. His pictures do not resemble reality, but the exotic paradise he envisioned.

Even the German writer benefited from these desires, which can be seen in his fictional travel reports of a South Sea chief. The travel reports were published between 1915 and 1920 under the title The Papalagi. Fifty years after the book was published it became a cult book and more than 1.7 million copies were sold in the German language only.

Application of the term[]

The South Seas Mandate was the name of the Japanese mandate over certain islands following World War I.

The "South Seas trade" was a term used in Britain in the nineteenth century to denote sealing, whaling, island trading and other commercial ship-based activities in the Pacific.

See also[]

- South Sea (disambiguation)

References[]

- ^ "South Sea". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Polk, Dora Beale (1991). The Island of California: A History of The Myth (1995 reprint ed.). Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark Company. pp. 67–76. ISBN 0-8032-8741-0.

- Oceania

- Pacific Ocean