St Bartholomew's Day Massacre in the Provinces

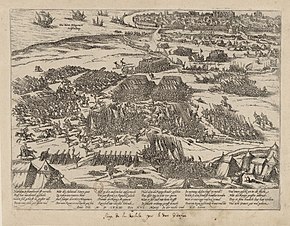

The St Bartholomew's Day Massacre in the Provinces refers to a series of killings that took place in towns across France between August and October 1572. A reaction to news of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in Paris, total deaths are estimated as between 3,000 to 5,000, roughly equivalent to those incurred in Paris. These events severely impacted Huguenot communities outside their strongholds in Southern France; the deaths combined with fear and distrust of Catholic intentions resulted in a large wave of conversions, while many others went into exile.

Responsibility was traditionally placed on Charles IX himself, who was alleged to have provided secret orders for the extermination of the Huguenots to municipal governors. However lack of direct evidence for this means historians now view the massacres as driven by zealous Catholics within provincial administrations or the court, who either knowingly or unknowingly deceived themselves as to the Kings wishes regarding the fate of the Huguenots.[1]

Culpability[]

For the Protestant polemicists of the sixteenth-century onwards, there was no question that the massacres had been personally directed by Charles IX and his secret council, and this was largely the position adopted by historians into the nineteenth-century.[2] However, these assumptions began to unravel as historians investigated the archives in the early twentieth-century.[3] They discovered Charles despatched two sets of letters to the provinces, on 24th and 28 August respectively, in which he ordered recipients to comply with the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and protect local Protestants from violence.[4]

Although Calvinist historians were aware of these instructions, they suggested they were simply a cunning charade to disguise his true orders to his governors, which would be delivered orally.[3] There is little evidence for this assertion, since the councillors of Rouen were rebuked by the king for failing to keep the peace, and after the massacre in Lyon in September local officials critiqued it in their correspondence with the king, fearing his disapproval.[5][6] Indeed, by the end of September they had removed their prior endorsement of the massacre, to bring themselves into line with royal policy.[5]

However, this does not absolve Charles from all responsibility and it appears he initially sent verbal orders to Lyon and Bordeaux among others. Their nature can be deduced from the letter of 2 September from François de Mandelot, Governor of Lyon, announcing he had arrested the Huguenots and seized their property.[7] Once he had cooled, he countermanded all verbal orders he had sent out.[7] It is thus clear then that the orders did not contain instructions to commit a massacre.[7] His vacillations did not end there however; when Vaucluse approached him at a public banquet and attempted to clarify whether his orders included killing, Charles asked him to return the following morning to his chambers, where he told him in private that Huguenots in Provence should be spared.[8] This suggests those who wanted to extend the killings into the provinces included the hardline Catholic extremist nobles who were present at the banquet and whom Charles was uncomfortable at speaking against in public.[8]

In the days following the massacre, many of these nobles would write back to their respective provinces, insinuating that it was the kings wish that the Huguenots be eliminated throughout France. This includes the Duke of Anjou who instructed his subordinate as related to Saumar and Angers, the Duke of Montpensier who wrote a letter to Nantes, instructing them to kill their Huguenot population and the Duke of Nevers who personally led troops in the massacre of La Charité.[9][10][11] Many other hardline local representatives of towns, who had been to Paris on official business, likewise reported back that the king desired a massacre, as happened with Belin in Troyes and with Rubys in Lyon.[12][13]

Popular fury also plays a key part in explaining responsibility, as in towns such as Rouen and Lyon, where the governors did not wish to lead a massacre, and instead, the prisons where they were keeping the Huguenots in protective custody were broken into by angry mobs, who then set about killing all the Huguenots inside.[14][15]

Distribution of the massacres[]

In traditional scholarship, the provincial massacres were assumed to be part of a centrally planned scheme to eliminate all Huguenots. This meant explaining why they occurred in some towns but not others was taken to be a factor of which governors had followed orders and which had not.[16] Since the lack of orders from Charles means this theory has now been rejected, explaining what made a town likely to have a massacre has become more difficult.[16]

One observation is that all were towns where at one time Protestants had been a significant minority.[17] Further, many of them had experienced a violent history in the first three religious wars, with Orléans, Lyon, Bourges, Meaux and Rouen all having been seized by the Protestants in the first religious war, and some again in the second and third.[18] Toulouse and Troyes had both seen failed attempts at takeovers, the former a very bloody one, and La Charité had been granted to the Huguenots as a security town at the end of the third civil war.[19][20][21] By 1572, Bordeaux and Toulouse were both Catholic strongholds in largely Protestant areas, worrying the Catholic majority of the towns.[18] Gaillac had borne witness to two massacres previously, one in 1562 by Catholics, and another in 1568 by Protestant troops.[18] Saumar and Angers are exceptions to this pattern of violent civil war history, yet their massacres are also different in character to many of the others, largely the work of zealous officials with little popular involvement.[22]

Another explanation lies in the distribution of power and population. In towns such as La Rochelle, Montauban and Nîmes the Protestant ascendency was such that they could be little threatened by their Catholic population, and with their political power, could close the gates to any external threat.[23] Other cities such as Rennes and Nantes had fostered a tolerant and peaceful atmosphere over the last 10 years, largely untouched by the civil war.[23] Finally cities such as Reims and Dijon had reached such a dominant level of Catholicism, that their small Protestant populations were too weak and cowed to pose enough of a threat to be worth massacring.[23]

Montpellier and Dieppe largely fall outside this pattern, and as such can be explained by the way in which the news of the Paris massacre was received by the local government.[23]

Massacres[]

The massacres were generally organised in time, with a few notable exceptions, by their proximity to Paris, as many of them bloomed during the initial chaos when the king's intentions weren't clear.[24] Rouen is a notable exception to this, occurring 4 weeks after the violence in the capital, and at a time when the King's displeasure was well known and published.[15]

Meaux[]

Meaux would be the location of the first massacre outside of Paris, due to its extreme proximity to the city. News of the massacre arrived in the city in the middle of the 25th August.[25] The carrier of the news made his way to the procureur du roi of the town, Casset, and his followers, upon hearing the news, seized the gates, and began arresting all the Protestants he could find.[25] They were not however entirely successful, many Protestants were gathered in the suburb of grand marche and hearing of what was going on were able to scatter into the surrounding villages.[26] When Casset and his men arrived in the suburb they were left to take out their frustration on the women who had stayed behind to protect their property.[26] On the 26th Casset turned to liquidate the arrested Protestants who were filling the prisons, a list was drawn up of 200 names for execution, largely composed of merchants artisans and judicial officials.[26] The executions continued into the evening, but, unable to finish the exhausting work, the remainder of the killing was set aside for the following day.[27]

La Charité[]

La Charité differed from the other massacres in that it was imposed from outside the town, by troops under the command of Louis Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers.[11] The duke had been a key player in orchestrating the original plot to assassinate the Huguenot leadership in Paris that had accidentally set off the Paris massacre.[28] Elements of the population were however agitated to enthusiasm for involvement by letters arriving from Paris after the massacre there started.[29] The troops arrived on the 26th to perpetrate the massacre.[24]

Bourges[]

Bourges received news of the massacre on the 27th, by which time many of the town's Huguenots, including François Hotman had already fled the town due to the earlier news of the assassination attempt on Gaspard II de Coligny.[30] The town's mayor Jean Joupitre was keen to act on the massacre to eliminate the Huguenots of Bourges, but the municipal officers of the town were more sceptical, and keen to wait for confirmation or denial of the orders to kill Huguenots from the king.[30] As such for the moment the Huguenots were confined to the prisons of the town.[31] On the 30th the impasse broke and the Huguenots in the prison were killed.[31]

Orléans[]

Orléans received news of the massacre the same day as Bourges on the 27th.[24] The preacher Sorbin whipped up the population, urging them to follow the example of Paris in a letter he wrote from the city.[32] Popular bands formed to orchestrate the killings.[33] The first victim was to be a royal conseiller Champeaux who was cut down in his home by a band under Tessier La Court on Monday.[34] It was not until the following day that the massacre became general, as the ramparts neighbourhood was systematically assaulted.[35] The violence would continue for 4 days with a myriad of small bands breaking down doors, sometimes demanding money in return for sparing the occupants, but always going back on their word if money was delivered to kill them anyway.[36] Occasionally on their rounds they stopped off at taverns, narrating the slaughters they committed during the day to the patrons as they ate.[36] The massacre would be the bloodiest in France, with 1000 killed from a population of only 50,000.[35]

Saumar and Angers[]

Saumar and Angers were largely instigated into massacre by the work of one man.[22] Monsereau, a deputy of governor Puyguillard who travelled from the capital to execute the orders of Puyguillard and his superior Henri, Duke of Anjou.[22] He entered Angers on 29 August and made his way to the house of seigneur du Barbei, Condés lieutenant in the area.[22] Du Barbei was however, not present in the town, so Monsoreau contented himself with executing his brother.[22] Then he went to the house of the town's Huguenot minister, invited into the garden by the minister's wife he announced his orders 'from the king' to the minister, and, after allowing him a final prayer, shot him.[11] He continued in this fashion house to house, after a few hours, a crowd, getting wind of what he was doing decided to join in, and for a few hours there was a general massacre, before the authorities were able to clamp down on it.[11] Monsereau then moved on to Saumar to repeat this pattern. Puyguillard followed to Angers, unsatisfied with his partial work in the towns, however he was more easily bribed into looking the other way by the town's remaining Huguenots.[37]

Lyon[]

Lyons received news of events in Paris first on 27 August when information about the attempt on Coligny's life arrived from the kings letter.[38] This was followed by a similar letter from Lyons representatives in the capital Masso and de Rubys.[38] Rumours of the massacre began to filter into the town from merchants on the 28th, this was confirmed in the letter of Masso and de Rubys that arrived the same day, which urged the town to follow Paris' example, saying it was the kings will.[38] As tensions began to rise in the town the Huguenot minister Langlois was assassinated.[39] On the 29th a letter from the king arrived, delivered by du Peyrat urging governor Mandelot to keep the peace in the town but also containing secret instructions, to arrest and seize the property of the Huguenots.[39] Mandelot called the councillors to meet and discuss how they were to proceed, they agreed to arrest the Huguenots, and Mandelot sent out an order, before shortly thereafter rescinding it, fearful he didn't have enough troops, and ill inclined to rely on the towns militia.[40] As the situation began to deteriorate further Mandelot felt he could no longer wait for troop reinforcements.[40] The city gates were closed and after calling all the Huguenots to the town hall to hear an address, they were arrested.[39] The arresting was meant to be a protective custody, but it would be fatal for all those who came forward to the address.[39] The prisoners were too many for solely the towns main jail, La Roanne, so many were kept in the Franciscan and Celestines convent and the jail of the archbishops palace.[39] At this point on 30 August governor Mandelot was called away to the suburb La Guillotière, to deal with a potential disturbance there.[39] Whilst absent, a mob formed and broke into the two convents, killing all the prisoners they found inside.[39] He returned by the evening, but did little to stop the mob as it proceeded to then break into the archbishops palace and the Roanne.[39] A commission formed to lead the mob, under André Mornieu.[40] He summoned the prisoners in the Roanne and archbishops palace to abjure, about 50 of them did, and they were sent to the Celestines monastery, spared.[40] Of the remaining 263 in the archbishops palace, none would be spared.[40] Later in the evening the mob advanced on the Roanne and the 70 Protestants inside were killed, Calm would not be restored until 2 September, by which time between 500 and 1000 Huguenots were dead.[40] Mandelot professed anger at the massacre, offering a reward for the handing over of the perpetrators to him, though he did little to bring this about practically.[41]

Some Protestants escaped the massacre by fleeing to nearby Montluel a town under the Duke of Savoy's dominion.[42] Others hid in the city, having not attended the meeting Mandelot organised.[42] Two consuls opposed the decision of their colleagues in endorsing the massacre on 18 September, the sieur de Combellande and the sieur d’Aveyne, who lodged a written protest.[43] The consulate would itself renounce the massacre by the end of September as the kings position became more clear.[43]

Troyes[]

Troyes received word of the massacre on 26 August, spreading panic among both the Protestants and Catholics.[44] The council reintroduced the civil militia and placed guards on the gates.[44] A curfew was instituted and weapons banned.[44] De Ruffe the governor of Angoulême passed by the town on his way elsewhere and told those he saw that it was the king's will that the Huguenots be executed.[44] This was contradicted by an abbot who passed through on the 30th and told the town the king had written that the Huguenots are to be protected.[44] Nevertheless, the town's bishop hatched a plot for a celebration of the Catholic victory on the 31st.[44] Some of those who were called to participate warned their Huguenot neighbours of his intentions, allowing some Huguenots to be hidden by their neighbours.[45] After receiving a letter endorsing massacre from the hardline Belin who was in Paris to petition the King against a Huguenot church, the bailli de Vaudrey orders the arrest of the Huguenots on the 30th, either to protect them or to stop their sedition.[45] On 3 September the mayor Nevellin presents a letter received from the king to the council, detailing his intentions regarding the maintenance of the peace edicts.[45] By this point Belin was back in Troyes, and he advocated again for massacre, citing the occurrence of a massacre in Paris as proof of his position. Most of the other councillors leave the chamber in shock and disapproval at his line, yet do little to stop his subsequent plans.[46]

Belin finds a willing collaborator in his plan in de Vaudrey who had long been an enemy of the Huguenots.[46] They set about organising the murder of those in the prisons.[46] The massacre would be smaller than in many other towns, with only 43 Huguenots killed in total.[47] To do the work they employ prison guards, the executioner having refused to be involved, several other Huguenots being killed in the streets by angry Catholics.[48] The massacre would begin on 4 September with each called up from their cell to be dispatched one at a time.[48] After killing 36 in the prison they would spend the next few days searching for those that might be hiding around the town.[49]

Rouen[]

Rouen receives news of what had happened in Paris around the same time, in a letter to the governor Carrouges from the King, which bemoaned the lamentable sedition that had befallen the capital.[50] Yet for a while Carrouges and the council of 24 were able to keep control. The conseiller echevins kept watch around the hotel de ville for several nights to ensure order was maintained and keep watch over the town.[15] Several days later the Protestants were locked up for their own protection as they had been in many other cities and the guard around Rouen was reinforced.[15] Some Huguenots would go willingly, feeling prison was likely more safe than their homes at a time like this, others refused to go, or instead fled abroad, to England and Geneva.[15] During this time the Catholic population attacked several nearby chateaus of absent or dead Protestant nobles.[15] Carrogues was dispatched to tour the province of Normandy and ensure peace was kept.[51]

This uneasy peace was broken on 17 September when, a mob, under the leadership of Laurent de Maromme who had prior been involved in the massacre of Bondeville and the curate of the St Pierre church Montereul seized the city.[52][53] They locked the gates and then first stormed the various prisons where the Huguenots were being kept, killing them all, and after having completed that devolved into breaking into houses searching for stragglers and looting for the next 4 days before order was restored.[53] The bodies were buried in rudimentary mass graves in the ditches of Porte Cauchoise.[54] The 300-400 victims of the massacre were of generally humbler origins than in other cities, the rich Huguenots having been able to leave, or able to buy off their attackers.[53]

Bordeaux[]

Bordeaux is one of the two cities we know that the king sent, and then countermanded secret instructions to, along with Lyon.[7] A public order to protect the Huguenots was published by the Parlement.[55] Yet this was accompanied by governor Montferrands order, forbidding Huguenot worship which had been permitted some distance away from the city by the Peace of Saint Germain in 1570.[56] Things remained relatively calm in the city until on 3 October Montferrand after having received a private visit from the son in law of Admiral Villars, appeared before the city jurats, claiming he had a list of Huguenots that the king wanted killed.[56] He would not however produce this list when requested by the jurats, and no record of it has ever been found.[55] He would proceed to carry out the massacre, largely free of popular involvement, as had been the massacres of Troyes and La Charité utilising 6 companies of his soldiers to execute it.[57] As in most other cities, the massacre would represent an opportunity for plunder as well.[56] In total 264 persons are recorded as having been killed in Bordeaux, as compiled in a report by the Parlement itself.[58]

Toulouse[]

Toulouse like much of the south received the news fairly late. Upon doing so the provincial Parlement and city magistrates tried to keep order, fearful of the consequences of any unrest.[59] The Huguenots were arrested for their own protection as they had been in many towns.[59] On 3 October having heard from some recently arrived envoys that the massacre of the Huguenots was the king's will, an angry mob broke into the prisons and massacred those inside, including 3 Protestant judges of the Parlement.[59][58] In total around 200-300 were killed in these attacks.[58] The Parlement meanwhile, following the lead of these envoys, sent orders to massacre out into the surrounding regions under the Parlement's authority, including the town of Gaillac.[60]

Gaillac[]

Gaillac represents largely a subsidiary massacre of that perpetrated in Toulouse, having been instigated by the Parlement of Toulouse itself.[60]

Minor massacres[]

There would also be violent disturbances in several other smaller urban centres, including Albi, Garches, Rabastens, Romans, Valence, Drôme and Orange.[61]

Avoided massacres[]

Nantes[]

Nantes would receive a letter for its mayor from the hardline governor Louis, Duke of Montpensier heavily implying that it was the king's wish that a massacre occur in Nantes without explicitly saying so.[62] The mayor decided however to just pocket the letter, keeping it secret until such time as he had the king's letter to hand, which urged the maintenance of peace in the provinces.[62] When he had both he called an assemblee generale and read both letters to the assembled delegates, they voted to safeguard the town's Protestants, and there was no further incident in the town.[62]

Aix[]

In Vaucluse's memoirs, he records that de la Molle was dispatched by the hardline governor of Provence to Paris, to find out what the king's wishes were regarding the Huguenots, as reports had filtered through that the king desired them massacred.[60] When after several weeks de la Molle did not return, Vaucluse was sent in his stead to go to Paris and report back.[60] As Vaucluse was approaching Paris he crossed paths with de la Molle going the other way, with alleged confirmed orders to massacre the Huguenots of Provence.[60] Sceptical of this Vaucluse came to the king while he was having a banquet, to ask him directly what his will was on the matter.[60] The king was unwilling to speak on the issue in front of his zealous guests, but urged Vaucluse to come back the next morning, during which time he confided in Vaucluse that it was not his wish for any massacre in Provence.[60] Vaucluse hurried back to Provence, overtaking de la Molle on route, and thus aided the averting of the massacre in Aix.[60]

Aftermath[]

While around 3000-5000 Protestants would directly die as a result of these massacres, the far larger result was that obtained in the subsequent wave of defections back to Catholicism. Though only 300 had been killed in Rouen, the community shrank from 16500 pre massacre to around 3000 post massacre.[63] The majority either abjuring, or going as refugees to Geneva and England. At least 3000 made some form of formal reconciliation with the Catholic church in the city, be it through rebaptisms, venerating the mass or abjuration documents.[64] 174 Rouennais were recorded in the Rye census in Sussex in November, with a record of 16 more families to come.[64] In Troyes we see a similar wave, with so many seeking to reconcile with the Catholic church that the town had to hire a special priest to hear the confessions.[65] Pithou records 20 families who emigrated from Troyes in the wake of the massacre, mostly to Geneva.[65] This trend of abjurations and exile occurred even in towns in the north that had experienced no massacre, Protestants ill inclined to trust any royal guarantee of safety going forward.[63]

A general feeling of defeatist despair overcame the northern Protestants, accompanied with soul searching as to how their god could have allowed this to happen, with some concluding it was punishment for their sins.[66] It further spurred the formation of Protestant resistance theory, to allow disobedience to an unjust king.[67]

The king despite his opposition to the massacres, decided not to let a good opportunity go to waste, and in early 1573 he banned Protestants from serving in royal office.[68] At the same time, the heartland Protestant cities of the south, entered open rebellion against the king, beginning the fourth of the French Wars of Religion as the king tried and failed to siege La Rochelle back into obedience with the crown.[69]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 215.

- ^ Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 207.

- ^ a b Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 208.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 209.

- ^ a b Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging memory: the aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 444. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 210.

- ^ a b c d Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 211.

- ^ a b Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 212.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots: in Two Volumes Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 512.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 214.

- ^ a b c d Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 223.

- ^ Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. pp. 145–6. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: the Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 438. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: the Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 439. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b c d e f Benedict, Phillip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0521547970.

- ^ a b Benedict, Philip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomews Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21, 2: 207–8.

- ^ Holt, Mack (2005). The French Wars of Religion 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780521547505.

- ^ a b c Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21, 2: 221.

- ^ Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the French Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Greengrass, Mark (1983). "The Anatomy of a Religious Riot in Toulouse in May 1562". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 34, 3 (3): 367–391. doi:10.1017/S0022046900037908.

- ^ Thompson, James (1909). The Wars of Religion in France: 1559-1576. Chicago University Press. p. 416.

- ^ a b c d e Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomews Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 222.

- ^ a b c d Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomews Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 224.

- ^ a b c Thompson, James (1909). The Wars of Religion in France 1559-1576: the Huguenots, Catherine de Medici and Phillip II. Chicago University Press. p. 450.

- ^ a b Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 505.

- ^ a b c Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 506.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 507.

- ^ Holt, Mack (2002). The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521892783.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 216.

- ^ a b Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 511.

- ^ a b Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 512.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 508.

- ^ Holt, Mack (1995). The French Wars of Religion 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780521358736.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 509.

- ^ a b Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion 1559-1598. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781408228197.

- ^ a b Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2 (2): 205–225. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00000510.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). The Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 512.

- ^ a b c Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: The Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 438. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: The Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 439. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b c d e f Baird, Henry (1880). The Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 514–5.

- ^ Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: The Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 445–6. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memory: The Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomews Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 446. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b Mingous, Gautier (2020). "Forging Memories: The Aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Lyon". French History. 34 (4): 443. doi:10.1093/fh/craa055.

- ^ a b c d e f Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ a b Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. pp. 152–3. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0521547970.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 519.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 520.

- ^ a b c Benedict, Phillip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 0521547970.

- ^ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 521.

- ^ a b Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 213.

- ^ a b c Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 522.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacre in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 221.

- ^ a b c Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots in Two Volumes: Vol 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 523.

- ^ a b c Holt, Mack (1995). The French Wars of Religion 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780521358736.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 212.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 206.

- ^ a b c Benedict, Phillip (1978). "The Saint Bartholomew's Massacres in the Provinces". The Historical Journal. 21 2: 217.

- ^ a b Holt, Mack (1995). The French Wars of Religion 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780521358736.

- ^ a b Benedict, Phillip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 0521547970.

- ^ a b Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0719046947.

- ^ Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion 1559-1598. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 9781408228197.

- ^ Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion 1559-1598. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 9781408228197.

- ^ Benedict, Phillip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0521547970.

- ^ Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion 1559-1598. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781408228197.

- 1572 in France

- Conflicts in 1572

- 16th-century massacres

- Massacres in France

- Massacres of Christians

- Political repression in France

- Protestant–Catholic sectarian violence