St Mary's Church, Portsea

| St Mary's Church, Portsea | |

|---|---|

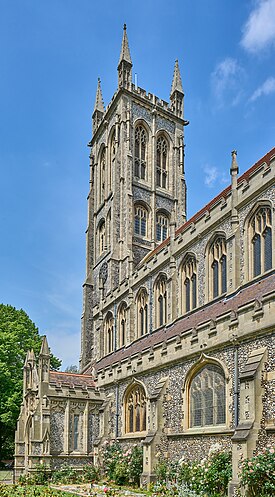

The tower, south porch and nave | |

St Mary's Church, Portsea Location within Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 50°48′13″N 1°04′35″W / 50.8035°N 1.0764°W | |

| Location | Portsea, Portsmouth, Hampshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | portseaparish.co.uk |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Founded | c. 1164 |

| Dedication | Mary, Mother of Jesus |

| Consecrated | 10th October 1889 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Parish church |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 10th January 1953 |

| Architect(s) | Sir Arthur Blomfield |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Years built | 1887-1889 |

| Construction cost | £40,000 (1889) |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 210 feet (64 metres) |

| Tower height | 167 feet (51 metres) |

| Materials | Flint |

| Bells | 8 |

| Tenor bell weight | 17 long cwt 0 qr 7 lb (1,911 lb or 867 kg) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Portsea |

| Deanery | Portsmouth |

| Archdeaconry | Portsdown |

| Diocese | Portsmouth |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Bob White |

St Mary's Church is the main Church of England parish church for the areas of Portsea and Fratton, both located in the city of Portsmouth, Hampshire. Standing on the oldest church site on Portsea Island, the present building, amongst the largest parish churches in the country,[1] has been described as the "finest Victorian building in Hampshire".[2] It is at least the third church on the site[3] and has been designated a Grade II* listed building by Historic England.[4] Former regular worshippers here have included Charles Dickens, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and Cosmo Lang.[5]

History[]

First church[]

Though Portsmouth was generally seen to be founded in 1181 by Jean of Gisors,[6] in 1164, the Norman lord of the manor, Baldwin de Portsea, informed Henry de Blois, the Bishop of Winchester, that he was giving the church of St. Mary, together with some land, cattle, sheep and hogs to the prior and canons of Southwick Priory.[3] This means there was already a church on the site at the time, and the Doomsday Book records 31 families lived in what is now modern-day Buckland, Copnor, and Fratton.[3] Not much is known about this early church, but it is recorded a tower was added to the church in Tudor times,[3] and that the roof was low, featuring dormer windows.[7]

Until the 19th century, St Mary's church would have been surrounded by farms and fields, and it was not until the 19th century, when the dockyard and population began to grow, that a new church was required. A gallery was built within the church to increase capacity, featuring box pews, but eventually, it was decided to rebuild the church.[3][8]

Second church[]

The new church was built in 1843 at a cost of £5,000[8] (equivalent to £302,000 in 2017[9]) and was designed in the Early English Gothic style by Thomas Ellis Owen.[10] It incorporated the Tudor west tower of the old church.[3] This church did not last until even the end of the century, for although it was lacking both in light and ventilation, it was smaller than the newly built Roman Catholic cathedral and so it was demolished in 1887.[3]

Present church[]

Following the demolition of the 1843 church, a temporary iron church was erected on the north side of the churchyard. The vicar at the time, Canon Edgar Jacob, had originally planned on raising £15,000, treble the cost of the 1843 church, to build the new church, but an anonymous Portsmouth resident offered to double what the parish raised. Consequently, grander plans were presented to Sir Arthur Blomfield, the architect employed by the Diocese of Winchester, who subsequently designed the present building.[3] Jacob wanted this church to be an inspiration for those in the city, and Blomfield intended it to be the "chief parish church of a great town".[8]

The foundation stone was laid by Victoria, Princess Royal, on 9 August 1887,[3] and a plaque near the entrance marks this event.[8] In 1891, the then First Lord of the Admiralty, W. H. Smith, died. It was discovered shortly after that it was Smith who was the anonymous donor in 1887. By the time of his death, he had given £28,000 towards the cost of building the church.[3] Construction of the church lasted until 1889, and it was consecrated by the Rt Revd Harold Browne, Bishop of Winchester, on 20 October 1889.[3][8] The final cost of the church was £44,000 (equivalent to more than £3,600,000 in 2017[9]).[3][8] The new church was significantly larger than either of the previous two churches, being easily able to contain the entire area of the old church within its walls.[11]

On 25 August 1894, the church was broken into and set alight by crumpling the altar cloth, pouring spirits nearby and turning on the gas. Though there was severe damage to the communion table, the fire burnt out before taking hold of the church.[12]

In 1927, the Diocese of Portsmouth was created, being carved out of the Diocese of Winchester, and numerous discussions were held as to which church would become cathedral. St Mary's was put forward as a possible pro-cathedral, but it was felt that due to its commitment to the many mission churches in the area, it was unsuitable. The Church of St Thomas became cathedral, but it required doubling in size before it was as large as St Mary's.[8][13][14]

The church remained essentially as completed until the Second World War, when during the Portsmouth Blitz, two bombs narrowly missed the church, falling on Woodland Street immediately behind the church, on 24 August 1940.[3][15] Though the church itself was not hit during the bombing, the shockwave from these two bombs shattered most of the glass of the large east window.[3]

When services resumed after the war, the east window was not repaired immediately, for wooden panels covered much of the window until 1952.[16][13]

In 1989, roof repairs were necessary, for rainwater was leaking into the organ.[17] The roof was repaired again in 2000, which also including retiling the entire nave roof.[18]

Restoration of the tower commenced in early 2008, a project costing £700,000, of which £300,000 was given by English Heritage[8] and £100,000 by the Landfill Communities Fund. The project involved erecting one of the largest suspended scaffolds in the world at the time, replacing windows and metalwork, renovating stonework, and repainting the clock face. The tower reopened in August 2009.[19]

Architecture[]

Plan[]

The church was designed in the Neo-Perpendicular Gothic style and features a west tower, an aisled nave of six bays, north and south porches, chancel, and lady chapel. There are vestries towards the east end of the church, as well as lean-to narthexes on the north and south faces of the tower.[4] The church is 210 feet (64 metres) long.[3]

Exterior[]

The chief feature of the church is the landmark west tower, built of four stages, topped by tall corner pinnacles.[4] Likely inspired by the tall church towers of East Anglia,[20] the present tower rises to 167 feet (51 metres) high.[19] There is a clock face on each side of the tower, except the eastern side where the nave roof meets the tower wall. The clock was installed by Gillett & Johnston of Croydon.[8] The completion of the tower made the church the highest building in Portsmouth, surpassing St Thomas' Church, until the building of the Guildhall in 1890.[21]

The south-facing nave aisle has a low projecting porch where it meets the tower, featuring stepped offset buttresses each terminating with stone pinnacle, facing stone gable with traceried stone panels, and an embattled parapet. To the left of the porch are three Perpendicular style 3-light windows, featuring flanking stepped buttresses.[4]

The nave has 6 paired 2-light Perpendicular style clerestory windows, flanking stepped pilasters each rising to a crocketed pinnacle. At the junction of the nave with chancel is an octagonal stairs access turret with at top a Tudor type flat arch and traceried window to each face. To the right of the aisle is the projecting 2-bay Lady Chapel with two 5-light wide Perpendicular style windows. Flanking stepped buttresses with diagonal buttress to each corner and again, an embattled parapet.[4]

The chancel is lower and narrower than the nave, with stepped offset buttresses each rising into a crocketed pinnacle. The chancel is lit by a large 7-light Perpendicular style window. To the right of the chancel is the north transept, containing the 2-storey vestry, sacristy and organ loft[4] There is an octagonal stair turret on the south side of the chancel, giving access to the roof. The stair turret, like most of the church, has an embattled parapet.

The north side has aisle, nave and chancel windows all similar to the south side. To the right of north aisle within the 5th bay is a projecting porch, with flanking panelled pilasters, and a stone parapet.[4]

Interior[]

The interior is light, open, and airy.[4] The main entrance is located under the tower, and there is a decorative lierne vault between the west window and the tower arch. The west window itself is of 4-light stained glass, dedicated to the memory of W. H. Smith.[13] The tower is notably thinner than the nave and, as such, the tower arch does not span the entirety of the nave's west wall. Above the tower arch is a three-light stone window frame, the middle panel of which provides views of the church from the ringing chamber behind it.[4]

The nave is tall and wide, featuring a large arcade spanning the height of both aisles; each pointed arch in the arcade separated from the clerestory above it by a thin triforium. The nave is separated from the tower by an iron rood screen. The north nave aisle windows depict scenes from the Old Testament, that of the south nave aisle from the New Testament. There is also a royal coat of arms in the south aisle, dating from 1822, and which was originally placed in the medieval church.[13]

The nave has a spectacular hammerbeam roof, the supports for which start midway up the clerestory buttresses. The roof is made out of oak and features gilded bosses.[13]

The chancel starts with a wooden barrel vault, but past the chancel arch becomes a stone lierne vault. Behind the altar is a large 7-light window, the glass for which was made in 1952, after the previous glass was mostly destroyed by a bomb in 1940.[13]

Building materials[]

The building is primarily built externally from flint, with Bath stone as dressing.[4] The roof of the nave and aisles is tiled, that of the tower and chancel covered in lead. The font, which stands in the centre of the nave, is built from alabaster, taken from Staffordshire. The pulpit, which is of "exceptional size", is made of Hamstone from Somerset.[13]

Organ[]

With 2,622 pipes, the present organ is amongst the largest and finest in any parish church on the South Coast. It was built by J. W. Walker & Sons, beginning in 1888, during the construction of the new church. The new organ was designed from the outset to be of "Cathedral-size" proportions, with four manuals. The cost of the new instrument was £1,784, and by early 1889, £873 of the total had been raised.[13][12]

For the first two years following installation in 1889, the organ only contained two manuals and pedals, though the organ console was prepared as a four-manual instrument. The organ was later completed in late 1892 thanks to a gift by W. H. Smith's widow. The proposed solo organ, which would have been used via the fourth manual, was never installed, and the extra manual was thus redundant until it was removed in 1965.[12]

The organ was consecrated on 31 October 1892, where the choir sang the anthem “Sing, O heaven, and be Joyful, O Earth!”, and the sermon was preached by the Bishop of Winchester, the Rt Rev'd Anthony Thorold.[12]

Though Blomfield had designed an ornate organ case, it was not installed until 1901.[8] The organ case and screen is made out of solid oak and is dedicated in memory to the victims of the Boer War. The case and screen have a complex and intricate design, depicting the church building and fabric in various carvings. A Service of Music and Dedication of the Organ Screen was held on 12 October 1901. During the service, Chopin's "Marche Funebre" was played as an act of remembrance to those whose names are inscribed on the organ screen.[12]

Though plans were made several times to further enlarge the organ, it was not until the late 1920s that proposals were seriously considered. However, these also came to nothing, due to the Great Depression and then the Second World War, the latter of which caused considerable damage to Portsmouth. It was therefore not until the late 1950s that long-overdue maintenance work could be considered again. In 1961, the new vicar, Freddy Temple, began a vigorous fundraising campaign to raise funds for the organ, which by this time was approaching its 70th anniversary. Temple enlisted the help of several famous architectural historians and musicians, including Douglas Fox, and John Betjeman.[12]

In 1962, Walkers & Sons, who manufactured the instrument back in the 1890s, were invited to tender for the project. In a report from 9 March 1962, they proposed a complete modernisation in the contemporary style, with new electro-pneumatic action, new console, tonal changes and additions, an increase of manual compass to 61 notes and pedal compass to 32 notes, and pitch change, all for the price of £10,000. The parish was unable to raise the required amount of money, even with the help Temple enlisted, so the scope of the project was reduced to include only dismantling, cleaning and reassembling the pipework, and a new blowing plant, which cost £7,300. The organ, therefore, escaped again from major tonal changes, though the quality of the workmanship in 1962 was such that the "restored" organ was inferior to its original condition. The overhauled organ was rededicated at Evensong on Sunday 13 June 1965.[12]

In 1981, George Martin and Partners, a local firm, undertook further work on the organ, which involved lowering the pitch of the entire instrument.[22]

2020-2023 restoration[]

In F2020, a three-year restoration of the organ began, the most comprehensive in its history. The project had a substantial boost by an enormous grant from the National Heritage Lottery, totalling £764,000.[23] A requirement of their award is the parish now has to raise £64,000. As of June 2021, £29,800 has been raised by the church.[24]

The project involves dismantling the entire instrument and sending it to Nicholson & Co's workshop, located in Malvern, Worcestershire. Whilst there, the pitch change in 1981 will be reversed, new electro-pneumatic mechanisms will be manufactured, the 1965 console to be replaced with a replica of the original console, all pipes to be thoroughly cleaned and returned to original Victorian condition, the reeds to be re-voiced with new tongues, the electrical system replaced, and the casework waxed. The pipes left the church on 12 November 2020.[17][24][25]

Whilst the Walker organ is being restored, a Viscount Regent 365 digital organ, featuring three manuals,[26] has been lent to the church courtesy of South Coast Organs and Viscount Classical Organs UK.[27] Due to the cavernous size of the building, thirteen amplifiers have been installed to project the sound of the Viscount organ across the church.[27]

Bells[]

In 1764, Lester & Pack of Whitechapel, London, cast a peal of six for the church, hung in the small, Tudor tower the old church possessed.[28] When the new church was nearing completion in 1889, four of these bells were transferred from the old tower to become the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 6th of a "new" ring of eight, accompanied by four newly cast by bells, also by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. All eight bells were hung in a new timber frame[29] in the uppermost stage of the tower. The tenor bell weighed approximately 16 long hundredweight (810 kilograms) and was in the key of E.[30]

The "new" ring of eight were first rung on the consecration day, 10 October 1889, by a specially selected band of ringers from across the Diocese of Winchester. The "new" ring of eight were considered to have a "remarkable depth of tone", but were highly challenging to ring, even by the experts selected, for the bells were hung some 70 feet (21 metres) above the ringing chamber. This caused issues, not just because of the sheer length of "elasticated" rope, but also significant tower movement from the bells being hung so high in it. Further complications were caused by less than sympathetic building practices in the belfry, involving the staircase crossing the paths of the ropes. The Bell News records on the October 26th issue of that year that, the band were forced to give up their peal attempt due to "sheer exhaustion".[30]

Many full peals were rung on the bells despite their difficulty, including some of the first "Surprise" methods to be rung in Hampshire.[31] By 1932, however, the bells were in a sorry state. It become clear neither the fittings nor frame were able to carry on, and so the tower was closed to all ringing until the financial situation presented itself to allow the bells to be restored. This was likely to have been for some considerable time, given the poor nature of the parish, had it not been for the intervention of Mr F. Hopkins of the Barron Bell Trust, who offered to gift the cost of recasting and rehanging all eight bells, which was accepted. Consequently, the old bells and frame were removed in late 1932, the bells and frame being sent to John Taylor & Co in Loughborough, Leicestershire, for complete recasting and restoration.[1]

The restoration involved recasting all eight bells, increasing them in weight slightly so the tenor now weighed 17 long hundredweight and 7 pounds (867 kilograms),[32] and struck the note F. The bells were rehung in a brand new cast iron bell frame, hung some 25 feet (8 metres) lower in the tower, in the stage below the louvres. The bells were provided with all new fittings, including ball bearings, and Hasting stays.[1][8][33] The old bells had their inscriptions copied onto the new bells, that of the tenor having an addition, giving thanks to the Barron Bell Trust for donating them.[1] The bells were hung behind the glass windows of the third stage, so the windows were made soundproof, and as a result, the sound has to travel up to the former belfry level before it can be heard outside. This made the bells much more acceptable in volume outside, as the sound travels up and out, rather than down onto street level.[1]

The new ring of eight were dedicated on April 8, 1933, the service led by the then Archdeacon of Portsmouth, the Rt Revd Harold Rogers. Ringers from across the South East attended, including from Brighton, Christchurch (at the time in Hampshire, now in Dorset), Crawley, Guildford, Fareham, and the Isle of Wight, amongst other places. Following the service, the bells were rung for the first time. The merits of the restoration were immediately obvious, the sound and 'go' of the new bells was described in The Ringing World as "nothing short of excellent" and "amongst the finest peals of eight in existence".[1] Moving the bell frame down a stage had enabled tower sway to be reduced, and the rope length to be considerably lessened. Since then, the bells have had no major work done to them. They remain popular with visiting ringers, and the current ring of bells have had more than 200 full peals rung on them since their installation.[31] There is no local band at the church, so the bells are rung by volunteers from the Portsmouth District ringers, affiliated with the Winchester and Portsmouth Diocesan Guild of Ringers, or by visiting bands.[1][8][33]

List of vicars[]

The following priests have been Vicar of St Mary's:[34]

- 1878–1896; Edgar Jacob, later Bishop of Newcastle, then St Albans

- 1896–1901; Cosmo Gordon Lang, later Archbishop of York, then Archbishop of Canterbury

- 1901–1909; Bernard Wilson[35]

- 1909–1919; Cyril Garbett, later Archbishop of York

- 1919–1927; John Francis Lovel Southam[36]

- 1927–1939; Geoffrey Charles Lester Lunt

- 1939–1944; Henry Robins

- 1944–1961; Walter Smith[37]

- 1961–1970; Freddy Temple, later Bishop of Malmesbury

- 1970–1981; Ken Gibbons, later Archdeacon of Lancaster

- 1981–1991; Michael Brotherton, later Archdeacon of Chichester

- 1992–1998; Robert Wright, later Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons

- 2000–present; Bob White

See also[]

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary, Portsea. |

- ^ a b c d e f g "PORTSEA'S NEW BELLS - MUNIFICENT GIFT OF BARRON BELL FUND TRUST" (PDF). The Ringing World. 1933: 233–235. 1933-04-14.

- ^ "Saint Mary's Church - Church / Chapel in Portsmouth, Portsmouth". Visit Portsmouth. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "A Brief History". Portsea Parish. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "CHURCH OF ST MARY, City of Portsmouth - 1104279". Historic England. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Portsea St Mary". Explore Churches. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ Quail, Sarah (1994). The Origins of Portsmouth and the First Charter. City of Portsmouth. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-901559-92-X.

- ^ Scott, Kenneth. "St. Marys Church". www.kenscott.com. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Flint, Peter. A look around St Mary's Church, Fratton, Portsmouth (Documentary). 2015.

- ^ a b "Currency converter: 1270–2017". The National Archives. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ King, Alan (2011). Portsmouth Encyclopaedia. Portsmouth, Hampshire, UK: Portsmouth City Council, via Portsmouth Historic Libraries. pp. 72–73.

- ^ "St Mary's Church footprint and plans". Portsea Parish History. 2020. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "History of the Organ". The Organ Project. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h "History of Portsea Parish and St Mary's Church". The Organ Project, St Mary's Portsea. 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Knowles, Graeme (2006). Portsmouth Cathedral. Shropshire: RJL Smith & Associates Much Wenlock. ISBN 1-872665-94-2.

- ^ Norman, Malcom (2020). "Portsmouth Blitz Map". Visit Portsmouth. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) (password-protected) - ^ "St Mary's interior 1948". Portsea Parish History. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ a b "Blog". The Organ Project. 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Church Roof 2000". Portsea Parish History. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Portsmouth's St Mary's Church tower to reopen". The News (Portsmouth). 2009-08-11. Archived from the original on 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ "New parish church of St Mary, Portsea". Sense of Place South East. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Guildhall History". Portsmouth Guildhall. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ "St. Mary, Fratton Road [N00940]". National Pipe Organ Register. 1998-11-27. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Morton, Tom (2020-06-30). "St Mary's Church in Portsmouth gets £764,000 from National Lottery for organ restoration project". The News (Portsmouth). Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ a b "Frequently asked questions". The Organ Project. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Portsea". Nicholson & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ "Regent 356". Viscount Organs. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ a b "The Organ Project at St Mary's Portsea". South Coast Organs. 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ Colchester, Revd Walter Edmund (1920). Hampshire Church Bells: Their Founders and Inscriptions (PDF). New Milton, Hampshire, UK: Whiting Society of Change Ringers. p. 93.

- ^ "OUR CHURCH BELLS. THEIR CONDITION AND SURROUNDINGS" (PDF). Bell News. 24: 421. 1905-11-11 – via Central Council of Church Bell Ringers.

- ^ a b "ST. MARY'S, PORTSEA, HANTS". Bell News. 8: 352. 1889-10-26 – via Central Council of Church Bell Ringers.

- ^ a b "valid peals for Portsea, Portsmouth, S Mary, Hampshire, England". Felstead Peals. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hedgcock, James; Higson, Andrew (2015-12-07). "Tower details - Portsmouth, Hampshire, S Mary, Portsea". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Portsmouth, Portsea, St Mary". Winchester and Portsmouth Diocesan Guild of Bell Ringers. 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Benefice of Portsea (St Mary) (St Faith and St Barnabas) (St Wilfrid)". Crockford's Clerical Directory. Church House Publishing. 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ 'Cyril Forster Garbett, Archbishop of York: a biography' Smyth, Charles Hugh Egerton: London; Hodder & Stoughton; 1959

- ^ National Library of Wales

- ^ "Portsea Parish Magazine" December 1956 p2 Vicar's welcome

- Church of England church buildings in Hampshire

- Grade II* listed churches in Hampshire

- 19th-century Church of England church buildings

- Religious buildings in Portsmouth

- Anglo-Catholic church buildings in Hampshire