Stedinger Crusade

The Stedinger Crusade (1233–1234) was a Papally-sanctioned war against the rebellious peasants of Stedingen.

The Stedinger were free farmers and subjects of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen. Grievances over taxes and property rights turned into full-scale revolt. When an attempt by the secular authorities to put down the revolt ended in defeat, the archbishop mobilized his church and the Papacy to have a crusade sanctioned against the rebels. In the first campaign, the small crusading army was defeated. In a follow-up campaign the next year, a much larger crusader army was victorious.

It is often grouped with the Drenther Crusade (1228–1232) and the Bosnian Crusade (1235–1241), other small-scale crusades against European Christians deemed heretical.[1]

Background[]

Stedinger settlement[]

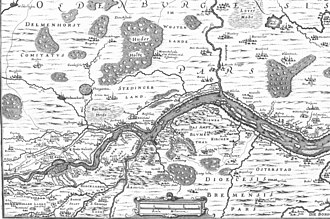

The Stedinger were the peasant inhabitants of the region between the Weser river and the lower Hunte, opposite Bremen. They eventually came to inhabit lands north of the Hunte as well. This marshy region was first cleared and settled only at the beginning of the twelfth century. The name Stedinger (or Stedinge in Latin documents) refers to the people, while the land is Stedingen (or in Latin terra Stedingorum, land of the Stedinger). The name derives from the German word Gestade, meaning coast or shore. Originally, in the early twelfth century, the Stedinger were known as Hollandi, that is, Hollanders, or simply rustici, farmers. When relations with their overlord later soured, they were dismissively referred to as bestie, beasts.[1]

Legally most of the Stedinger were subjects of the prince-archbishop of Bremen, the land being administered by his ministerials (serfs of knightly rank). Some were subjects of the count of Oldenburg north of the Hunte.[2] Already in 1106 they had received privileges from Archbishop conferring on them the right to freehold land and to found churches, as well as exempting them from some taxes. Collectively, these rights and privileges were known as the ius hollandicum, Hollandic right. By the early thirteenth century, the Stedinger formed a well-defined community called the universitas Stedingorum.[1]

Stedinger revolt[]

The grievances which led to open revolt were that the ius Hollandicum was not being respected. Specifically, the Stedinger complained that the archbishop was demanding more in tax than he was owed and that both he and the count intended to convert their freeholds into leases.[1]

In 1204, the Stedinger north of the Hunte rebelled against the count of Oldenburg, burning to the ground two of his castles. Their revolt spread south of the Hunte, where the archbishop's ministerials were driven off. The peasants stopped paying taxes and tithes to the archbishop and attacked his castles in 1212, 1213 and 1214. When Gerhard II became archbishop in 1219, he immediately set to work restoring his authority in Stedingen. Just before Christmas 1229,[a] he excommunicated the Stedingers for their continued refusal to pay taxes and tithes[2] (in the words of the Chronica regia Coloniensis, "for their excesses", pro suis excessibus).[1]

In December 1229, Gerhard joined forces with his brother, Hermann II of Lippe, and led a small force into Stedingen. They were defeated by the peasants on Christmas Day and Hermann was killed. In 1232, after 1 September,[1] Gerhard established a house of Cistercian nuns in Lilienthal for the salvation of his brother, who died, so Gerhard said in the foundation charter, "for the liberation of the church of Bremen".[2]

Investigation[]

After his defeat, Gerhard began preparing for a crusade against the rebels. He may have been inspired by the Drenther Crusade that Bishop Wilbrand of Paderborn and Utrecht had gotten in 1228 against his rebellious peasants.[3] Gerhard convened a diocesan synod on 17 March 1230,[b] whereat the Stedinger were declared heretics.[5] They were accused, among other things, of superstitious practices, murdering priests, burning churches and monasteries and desecrating the eucharist.[2] Cardinal Otto of San Nicola in Carcere and his Dominican assistant Gerhard, when passing through Bremen later that year,[c] gave strong support to Archbishop Gerhard's planned crusade.[5]

In June 1230,[d] Gerhard went to Rome to personally argue his case to the pope. Pope Gregory IX proceeded cautiously. He ordered the provost of Münster Cathedral to confirm the excommunication and the validity of the charges.[4] When the validity of the charges was confirmed, Gregory sent the letter Si ea que (26 July 1231) to Bishop and two prominent Dominicans from Bremen[e] ordering them to investigate the charges further and to call the Stedinger back to communion.[4] Si ea que already permitted the investigators to request military assistance from the neighbouring nobility if the charges proved true.[3] When the bishop of Lübeck's mission failed to bring about a resolution, Gregory ordered bishop and Bishops and to reinvestigate the charges one more time.[4]

By October 1232, Gregory was prepared to declare the crusade that Gerhard had requested.[4] On 29 October 1232, he sent the letter Lucis eterne lumine authorising the preaching of a crusade against the Stedinger to the bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg.[6] They were to preach the crusade in the dioceses of Bremen, Minden, Paderborn, Hildesheim, Verden, Münster and Osnabrück.[f][4] The bishops were authorized to recruit for the preaching all the Dominicans they needed.[3] The Emperor Frederick II also placed the Stedinger under the imperial ban.[2]

In his letter, Gregory accused the Stedinger of holding orgies and worshiping demons in Satanic rites—on top of their theological errors.[7] He instituted a graduated scale of indulgences of twenty days for attending a crusade sermon, three years for serving in another's pay and five years for serving at one's own expense. Full remission was available only to those who died in the enterprise, provided they confessed their sins. Those who contributed financially received an indulgence in proportion to their contribution, as determined by the preachers. The length of the campaign and thus of the service required to receive an indulgence was also at the discretion of the preachers based on military requirements.[3][4]

Crusade[]

Campaign of 1233[]

The initial response to the bishops' preaching was tepid; only a few local knights took the cross.[2] On 19 January 1233, Gregory IX addressed the letter Clamante ad nos to bishops Wilbrand of Paderborn and Utrecht, Conrad II of Hildesheim, , and asking them to assist the bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg in preaching the crusade.[g][4] The actual preaching was largely left to the Dominican Order, which had expanded rapidly in northern Germany in the 1220s. Conrad of Marburg, a noted heretic hunter and veteran of the Albigensian Crusade, also preached the crusade against the Stedinger.[1] As a result of the second round of preaching, an army was formed large enough for a summer campaign.[2]

In the winter of 1232–1233, the Stedinger captured the archbishop's fortress of Slutter.[4] In early 1233, they destroyed the wooden cloisters of the Cistercian , then under construction. They also reportedly captured a passing Dominican friar and beheaded him.[1] The bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg reported to the pope the Stedinger's victories and the reluctance of many to join the crusade because they considered Stedingen naturally fortified by its numerous rivers and streams. It is also apparent from the bishops' report that the Stedinger were regarded as a strong enemy.[3] When the crusaders finally arrived, they achieved some successes, but were defeated at in July.[2] Count , a relative of the count of Oldenburg, was among the dead.[1][3]

While the fighting was in progress in June, Pope Gregory issued a renewed call for a crusade. In the letter Littere vestre nobis (17 June 1233), addressed to the bishops of Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg,[4] he raised the partial indulgence previously granted into a plenary one, placing the Stedinger crusade on an equal footing with the crusades to the Holy Land.[1][2][7] Around the same time, he issued the decretals O altitudo divitiarum (10 June) and Vox in Rama (11–13 June)[h] directed at a different heretical movement, the Luciferians throughout Germany.[6] In Littere vestre nobis, the plenary indulgence (full remission) was granted not only to those who died (as before) but to all who had taken the cross (i.e., a formal crusade vow) and fought. This change in policy was probably both a response to the Stedinger's successes in the winter of 1232–1233 and a counterweight to the new crusade against the Luciferians,[i] to prevent resources and manpower from being diverted away from the unfinished Stedinger business (negotium).[4]

Campaign of 1234[]

A larger and more impressive army was raised in early 1234,[2] after the Dominicans preached the crusade throughout Brabant, Flanders, Holland, the Rhineland and Westphalia.[4] According to the Annales Stadenses, the response this time was enthusiastic, but Emo of Wittewierum records that there was widespread uncertainty over whether all those preaching the crusade had the correct authorization to do so.[4] The most serious incident Emo records took place in the Frisian region of Fivelgo. Two Dominicans preaching in Appingedam were attacked and had to flee for safety to Groningen. They subsequently preached against the Fivelgonians. Nearby, in a place called Stets, a local monk interrupted a Dominican's sermon and was imprisoned in Saint Juliana's Abbey in Rottum. Few crusaders were recruited in Fivelgo.[3]

Among those who joined the new army were Duke Henry I of Brabant, Duke Henry IV of Limburg, Count Floris IV of Holland, Count Otto II of Guelders, Count Dietrich V of Cleves, Count William IV of Jülich, Count Otto I of Oldenburg, Count , Count , the lords of Breda and Scholen and several barons from the county of Flanders.[1][2][3] All of these named men were related to the counts of Oldenburg.[3] The overall leader was the duke of Brabant. According to the Sächsische Weltchronik, it numbered 40,000 men; in reality it was probably closer to 8,000.[8]

The Stedinger army numbered 11,000, according to Emo of Wittewierum. Probably it did not exceed 2,000. They were poorly equipped next to the crusaders, lacking any armour and armed only with pikes and short swords.[8] According to the Annales Stadenses, the Stedinger leaders were Tammo von Huntdorf, Bolko von Bardenfleth and Ditmar von Dielk, all otherwise unknown.[j][1][8]

A last-ditch effort to prevent bloodshed was made by the Teutonic Order, which intervened with the pope on behalf of the Stedinger. On 18 March 1234, in the letter Grandis et gravis, Gregory ordered his legate in Germany, William of Modena, to mediate the dispute between the Stedinger and the archbishop. Since the conflict was not resolved before the spring campaign, either word of the pope's decision did not reach the crusaders in time or the archbishop ignored it.[2]

The crusader army assembled on the western bank of the Weser and march north. They used a pontoon bridge to cross the Ochtum and enter Stedingen. On 27 May 1234, they caught the peasant army in a field near and attacked its rear. It took several charges to break the wall of pikes. When the peasants broke formation to advance, the count of Cleves charged its flank. At that point the battle was won by the crusaders and a general massacre began. Women and children were not spared, but many peasants escaped into the marshes.[8] Among the dead on the crusader side was the count of Wildeshausen of the family of the counts of Oldenburg. Gerhard credited the intervention of the Virgin Mary for his victory.[1]

The dead after the battle of Altenesch were so numerous they had to be buried in mass graves. The sources vary in the number of dead they give: 2,000 (Chronica regia Coloniensis); 4,000 (); 6,000 (Annales Stadenses); or 11,000 (Baldwin of Ninove). These numbers cannot be taken literally, but they give an impression of the perceived scale of destruction. The emphasise the deaths of "their wives and children".[1]

The surviving Stedinger surrendered to the archbishop and accepted his demands.[2] Their freeholds were confiscated, those in the north to the county of Oldenburg, those in the south to the archbishopric of Bremen.[8] On 21 August 1235, in the letter Ex parte universitatis, Pope Gregory ordered the lifting of their excommunication.[k][2] According to Emo of Wittewierum, some Stedinger escaped to Frisia or found refuge in the north German towns. According to the Historia monasterii Rastedensis, those who fled to Frisia and established a community there—the terra Rustringiae—were attacked by the counts of Oldenburg later in the century.[1]

Legacy[]

Remembrance[]

After his victory at Altenesch, Archbishop Gerhard declared an annual day of remembrance to be kept in all the churches of the archdiocese of Bremen on the Saturday before the Feast of the Ascension. This was not a somber commemoration but a celebration of the liberation of the church. In Gerhard's instructions concerning the celebrations, 27 May 1234 was called the "day of victory against the Stedinger" (dies victorie habite contra Stedingos). He detailed the chants and hymns to be sung when and prescribed a solemn procession followed by an indulgence for twenty days afterwards to all who gave alms to the poor. This liturgy was practiced in Bremen down to the Reformation in the sixteenth century.[1]

The death of Hermann of Lippe in battle against the Stedinger was periodically remembered at the monastery of Lilienthal throughout the thirteenth century. Gerhard also established memorial days for his brother at Lilienthal and the monastery of Osterholz.[1]

The counts of Oldenburg also commemorated the crusade in their foundation of Hude, which the Stedinger had attacked in 1233. It was constructed on a monumental scale as a sign of Oldenburg domination of Stedingen. In endowing the church, Count specifically mentioned his father, Burchard, and uncle, Henry III, "counts of Oldenburg killed under the banner of the holy cross against the Stedinger" (comitum de Aldenborch sub sancte crucis vexillo a Stedingis occisorum).[1]

For the 700th anniversary of the Battle of Altenesch and entirely different commemoration was enacted in Nazi Germany. A replica Stedinger village was constructed at Bookholzberg and on and around 27 May 1934 a series of reenactments, speeches, musical performances and processions were held in honour of the Stedinger, who were held up as heroic defenders of their land and freedom against a predatory church.[1]

Historiography[]

Contemporary chroniclers recognised that a crusade against farmers required a clearer justification than the crusades to the Holy Land or the crusades against organised heresies. Alberic of Trois-Fontaines tried to connect the Stedinger to the devil-worshippers; others connected them to the Cathars. Neither connection is convincing.[1]

Hermann Schumacher, in his 1865 study of the Stedinger, concluded that the charges of heresy were baseless and even "meaningless". More recently, Rolf Köhn has argued that they were taken very seriously by contemporaries and reflected a real concern about the spread of heresy in Europe. The Stedinger Crusade has attracted attention from historians of peasant movements as well as historians of the Crusades. Werner Zihn argues that the defeat of the Stedinger began with their increasing marginalisation in the decades before the crusade. Their inability to attract external allies assured their defeat.[1]

Prior to the 1970s, the Stedinger Crusade was usually seen in an ideological light. Schumacher viewed the Stedinger as seeking liberation from feudalism. For the National Socialists, the Stedinger were heroic representatives of a free Germany fighting the oppressive and foreign church; while for the scholars of East Germany, they were an oppressed class of workers fighting back against the greed of the aristocracy.[1]

Notes[]

- ^ Maier places this "probably shortly before Christmas 1229" but after the death of the archbishop's brother.[3]

- ^ Most authors date this synod to 1230,[1][4] but Maier, following Rolf Köhn (1979), dates it to 21 March 1231.[3]

- ^ They had resolved a dispute over the bishopric of Riga, a suffragan of Bremen.[5]

- ^ Rist has Gerhard travelling to Rome six months after the death of his brother,[4] while Pixton has Cardinal Otto travelling through Bremen on his return from Riga after 23 July 1230 and before Gerhard's trip to Rome.[5]

- ^ The Dominicans were the head of the convent in Bremen and a papal penitentiary named John, probably John of Wildeshausen.[3]

- ^ Jensen limits the initial preaching to Minden, Lübeck and Ratzeburg,[2] while Rist does not mention Ratzeburg.[4]

- ^ Jensen says that in early 1233 Gregory expanded the area of preaching,[2] while Rist merely has him involving the other bishops in it.[4] He did not, however, charge the bishops of Paderborn, Hildesheim, Verden, Münster and Osnabrück with preaching themselves.[3]

- ^ Merlo incorrectly identifies Vox in Rama as directed at the Stedinger.[6][7]

- ^ These crusades have sometimes been confused. Duke Otto of Brunswick, Margraves John I and Otto III of Brandenburg and Landgraves Henry and Conrad of Thuringia joined the crusade against the Luciferians, which never materialized.[5]

- ^ Knödler provides different spellings: Boleke of Bardenflete, Tammo of Hunthorpe and Thedmarus of Aggere.[8]

- ^ Rist, who does not mention the battle of Altenesch, attributes the Stedinger's absolution to the diplomacy of William of Modena.[4]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Megan Cassidy-Welch (2013), "The Stedinger Crusade: War, Remembrance, and Absence in Thirteenth-Century Germany", Viator 44 (2): 159–174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Carsten Selch Jensen, "Stedinger Crusades (1233–1234)", in Alan V. Murray (ed.), The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (ABC-CLIO, 2017), vol. 4, pp. 1121–1122.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Christoph T. Maier, Preaching the Crusades: Mendicant Friars and the Cross in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Rebecca Rist (2011), "Pope Gregory IX and the Grant of Indulgence for Military Campaigns in Europe in the 1230s: A Study in Papal Rhetoric", Crusades 10: 79–102, at 83–86. A condensed version of her account is also found in Rist, The Papacy and Crusading in Europe, 1198–1245 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b c d e Paul B. Pixton, The German Episcopacy and the Implementation of the Decrees of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1216–1245: Watchmen on the Tower (Brill, 1995), pp. 375–377.

- ^ a b c Thomas W. Smith, "The Use of the Bible in the Arengae of Pope Gregory IX's Crusade Calls", in Elizabeth Lapina and Nicholas Morton (eds.), The Uses of the Bible in Crusader Sources (Brill, 2017), pp. 206–235.

- ^ a b c Grado G. Merlo, "Stedinger", in André Vauchez (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages (James Clarke & Co., 2002 [online 2005]), retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Julia Knödler (trans. Duane Henderson), "Altenesch, Battle of", in Clifford J. Rogers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, 3 vols. (Oxford University Press, 2010), vol. 1, pp. 39–40.

Further reading[]

- Donnar, Gustav. Kardinal Willhelm von Sabina, Bischof von Modena 1222–1234: Päpstlicher Legat in den Nordischen Ländern (+1251). Helsinki, 1929.

- Förg, L. Die Ketzerverfolgung in Deutschland unter Gregor IX. Berlin, 1932.

- Freed, John B. The Friars and German Society in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge, MA, 1977.

- Kennan, Elizabeth T. "Innocent III, Gregory IX and Political Crusades: A Study in the Disintegration of Papal Power". Guy Fitch Lytle (ed.), Reform and Authority in the Medieval and Reformation Church. Washington, DC, 1981: 15–35.

- Kieckhefer, R. Repression of Heresy in Medieval Germany. Liverpool, 1979.

- King, Wilson. "The Stedingers: The Story of a Forgotten Crusade". Transactions of the Birmingham Historical Society 1 (1881): 1–24.

- Köhn, Rolf. "Die Verketzung der Stedinger durch die Bremer Fastensynode". Bremisches Jahrbuch 57 (1979): 15–85.

- Köhn, Rolf. "Die Teilnehmer an den Kreuzzügen gegen die Stedinger". Niedersächisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 53 (1981): 139–206.

- Krollmann, Christian. "Der Deutsche Orden und die Stedinger". Altpreußische Forschung 14 (1937): 1–13.

- Oncken, H. "Studien zur Geschichte des Stedingerkreuzzuges". Jahrbuch für die Geschichte des Herzogtums Oldenburg 5 (1896): 27–58.

- Schmeyers, Jens. Die Stedinger Bauernkriege: Wahre Begebenheiten und geschichtliche Betrachtungen. Lemwerder, 2004.

- Schmidt, Heinrich. "Zur Geschichte der Stedinger: Studien über Bauernfreiheit, Herrschaft und Religion an der Unterweser im 13. Jahrhundert". Bremisches Jahrbuch 60–61 (1982–1983): 27–94.

- Schumacher, Hermann Albert. Die Stedinger. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Weser-Marschen. Bremen, 1865.

- Zihn, Werner. Die Stedinger. Die historische Entwicklung des Stedinger Landes bis ins 13. Jahrhundert. Oldenburg, 1983.

- Stedinger Crusade

- 13th-century crusades

- Conflicts in 1233

- Conflicts in 1234

- 13th century in the Holy Roman Empire

- 1230s in Germany