Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik

| Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik سليمان بن عبد الملك | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

Gold dinar minted under Sulayman, possibly in Damascus, in 715 or 716 | |||||

| 7th Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 24 February 715 – 24 September 717 | ||||

| Predecessor | Al-Walid I | ||||

| Successor | Umar II | ||||

| Born | c. 675 Medina, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 24 September 717 Dabiq, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | Dabiq, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Marwanid | ||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | Abd al-Malik | ||||

| Mother | Wallada bint al-Abbas ibn al-Jaz al-Absiyya | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

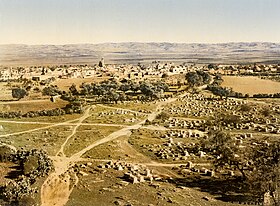

Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik (Arabic: سليمان بن عبد الملك, romanized: Sulaymān ibn ʿAbd al-Malik, c. 675 – 24 September 717) was the seventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 24 February 715 until his death. He began his career as governor of Palestine, while his father Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) and brother al-Walid I (r. 705–715) reigned as caliphs. There, the theologian Raja ibn Haywa al-Kindi mentored him, and he forged close ties with Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, a major opponent of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, al-Walid's powerful viceroy of Iraq and the eastern Caliphate. Sulayman resented al-Hajjaj's influence over his brother. As governor, Sulayman founded the city of Ramla and built the White Mosque in it. The new city superseded Lydda as the administrative capital of Palestine. Lydda was at least partly destroyed and its inhabitants may have been forcibly relocated to Ramla. Ramla developed into an economic hub, became home to many Muslim scholars, and remained the administrative capital of Palestine until the 11th century.

After succeeding al-Walid, Sulayman dismissed his predecessor's governors and generals. Many had been handpicked by al-Hajjaj and had led the war efforts which brought the Caliphate to its greatest territorial extent. Among al-Hajjaj's loyalists were the conqueror of Transoxiana (Central Asia), Qutayba ibn Muslim, who was killed by his own troops in an abortive revolt in anticipation of his dismissal, and the conqueror of Sind (the western Indian subcontinent), Muhammad ibn Qasim, who was executed. In the west, Sulayman deposed Musa ibn Nusayr, the conqueror of the Iberian Peninsula (al-Andalus) and governor of Ifriqiya (central North Africa), and had his son Abd al-Aziz, governor of al-Andalus, assassinated. Although he continued his predecessors' militarist policies, expansion largely stopped under Sulayman, partly due to effective resistance along the Central Asian frontiers and the collapse of Arab military leadership and organization there after Qutayba's death. Sulayman's appointee over the eastern Caliphate, his confidant Yazid, invaded the southern Caspian coast in 716, but withdrew and settled for a tributary arrangement after being defeated by the local Iranian rulers. Sulayman intensified the war with the Byzantine Empire, culminating in the 717–718 siege of Constantinople, which ended in an Arab defeat.

Sulayman died in Dabiq during the siege. His eldest son and chosen successor, Ayyub, had predeceased him. Sulayman made the unconventional choice of nominating his cousin, Umar II, as caliph, rather than a son or a brother. The siege of Constantinople and the coinciding of his reign with the approaching centennial of the Hegira (start of the Islamic calendar), led contemporary Arab poets to view Sulayman in messianic terms.

Early life[]

The details about Sulayman's first thirty years of life in the medieval sources are scant.[1] He was likely born in Medina around 675.[1][a] His father, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, belonged to the Umayyad clan of the Quraysh tribe, while his mother, Wallada bint al-Abbas ibn al-Jaz, was a great-granddaughter of Zuhayr ibn Jadhima,[3] a prominent 6th-century chieftain of the Arab tribe of Banu Abs.[4] Sulayman was partly raised in the desert by his Banu Abs kinsmen.[5]

At the time of his birth, the Caliphate was ruled by Sulayman's distant cousin, Mu'awiya I,[6] who had founded the ruling Umayyad dynasty in 661.[7] Following the deaths of Mu'awiya I's successors, Yazid I and Mu'awiya II, in 683 and 684, Umayyad authority collapsed across the Caliphate and most provinces recognized the non-Umayyad, Mecca-based, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, as caliph.[8][9] The Umayyads of Medina, including Sulayman, were therefore expelled from the city and became refugees in Syria,[1] where they were supported by loyalist Arab tribes.[10] These tribes elected Sulayman's grandfather, Marwan I, as caliph and formed the Yaman confederation in opposition to the Qaysi tribes, who dominated northern Syria and the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) and supported Ibn al-Zubayr.[11] By 685, Marwan had reestablished Umayyad control over Syria and Egypt.[12] Abd al-Malik, who succeeded him, had by 692 reconquered the rest of the Caliphate.[13]

Governorship of Palestine[]

At an unknown date, Abd al-Malik appointed Sulayman governor of Jund Filastin (the military district of Palestine), a post Abd al-Malik formerly held under Marwan.[1][14] Sulayman's appointment followed stints by the Caliph's uncle, Yahya ibn al-Hakam, and half-brother, Aban ibn Marwan.[15] In 701, Sulayman led the Hajj rituals in Mecca.[1] Before Abd al-Malik died in 705, he nominated his eldest son, al-Walid I, as his successor, to be followed by Sulayman.[1] Sulayman remained governor of Palestine throughout al-Walid's reign, which lasted until 715.[1][16] His governorship likely brought him in close contact with the Yamani chieftains who dominated the district.[17] He established a strong relationship with Raja ibn Haywa al-Kindi, a local, Yamani-affiliated religious scholar who had previously supervised the construction of Abd al-Malik's Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.[17] Raja became Sulayman's tutor and senior aide.[17]

Sulayman resented the influence of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the viceroy of Iraq and the eastern parts of the Caliphate, over al-Walid,[18] and cultivated ties with his opponents.[17] In 708 or 709, he gave refuge to the fugitive and former governor of Khurasan, Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, and his family, the Muhallabids. Al-Hajjaj had dismissed and imprisoned Yazid but he had escaped to Palestine.[1][17] There, Yazid used his tribal connections with the district's large Yamani Azdi population to gain Sulayman's protection.[19][20] Al-Walid was angered with Yazid's defiance of al-Hajjaj, so Sulayman offered to pay the fine al-Hajjaj had imposed on Yazid. He also sent the latter and his own son, Ayyub, in shackles to the Caliph, with a letter pleading for the Muhallabids' pardon, which the Caliph granted.[18][21] Yazid became a close confidant of Sulayman, who held him in "the highest regard", according to a report by the historian Hisham ibn al-Kalbi (737–819).[22] Hisham further noted "Yazid ... stayed with him [Sulayman], teaching him how to dress well, making delicious dishes for him, and giving him large presents".[22] Yazid remained with Sulayman for nine months, or until al-Hajjaj died in 714, and highly influenced and prejudiced him against al-Hajjaj.[23][24]

Foundation of Ramla[]

As governor, Sulayman founded the city of Ramla as the seat of his administration,[1][25][26] replacing Lydda, the Muslims' original provincial capital[1][25] and Sulayman's first residence in Palestine.[27] Ramla remained the capital of Palestine through the Fatimid period (10th–11th centuries).[28] His motives for founding Ramla were personal ambition and practical considerations.[29] The location of Lydda, a long-established and prosperous city, was logistically and economically advantageous. Sulayman established his capital outside of the city proper.[26] According to the historian Nimrod Luz, this was likely due to a lack of available space for wide-scale development and agreements dating to the Muslim conquest in the 630s that, at least formally, precluded him from confiscating desirable property within the city.[29] In a tradition recorded by the historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari (d. 1347), a determined local Christian cleric refused Sulayman's requests for plots in the middle of Lydda. Infuriated, he attempted to have the cleric executed, but Raja dissuaded him and instead proposed building a new city at a superior, adjacent site.[30] The historian Moshe Sharon holds that Lydda was "too Christian in ethos for the taste of the Umayyad rulers", particularly following the Arabization and Islamization reforms instituted by Abd al-Malik.[27] According to al-Jahshiyari (d. 942), Sulayman sought a lasting reputation as a great builder following the example of his father and al-Walid, founder of the Great Mosque of Damascus.[31] The construction of Ramla was his "way to immortality" and "his personal stamp on the landscape of Palestine", according to Luz.[32] In choosing the site, Sulayman utilized the strategic advantages of Lydda's vicinity while avoiding the physical constraints of an already-established urban center.[33]

The first structure Sulayman erected in Ramla was his palatial residence,[33] which dually served as the seat of Palestine's administration (diwan).[34] At the center of the new city was a congregational mosque, later known as the White Mosque.[35] It was not completed until the reign of Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720).[36] From early on, Ramla developed economically as a market town for the surrounding area's agricultural products, and as a center for dyeing, weaving and pottery. It was also home to many Muslim religious scholars.[37] Sulayman built an aqueduct in the city called al-Barada, which transported water to Ramla from Tel Gezer, about 10 kilometers (6 mi) to the southeast.[38] Ramla superseded Lydda as the commercial center of Palestine.[34] Many of Lydda's Christian, Samaritan and Jewish inhabitants were moved to the new city.[39] Although the traditional accounts are in agreement that Lydda almost immediately fell into obscurity following the founding of Ramla, narratives vary about the extent of Sulayman's efforts to transfer Lydda's inhabitants to Ramla, some holding that he only demolished a church in Lydda and others that he demolished the city altogether.[25] Al-Ya'qubi (d. 839) noted Sulayman razed the houses of Lydda's inhabitants to force their relocation to Ramla and punished those who resisted.[40][41] In the words of al-Jahshiyari, Sulayman "founded the town of al-Ramla and its mosque and thus caused the ruin of Lod [Lydda]".[31]

Jerusalem, located 40 kilometers (25 mi) southeast of Ramla,[42] remained the region's religious focal point.[43] According to an 8th-century Arabic source,[44] Sulayman ordered the construction of several public buildings there, including a bathhouse, at the same time that al-Walid was developing the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif).[30] The bathhouse was used for ablution by Muslims worshipping at the Dome of the Rock.[44] Sulayman is further credited by an anonymous 13th-century Syriac chronicler for building arches, mills and gardens in Jericho, but these were later destroyed by floods.[45] He also maintained an agricultural tract near Qutayfa, in the environs of Damascus, that was called "al-Sulaymaniyya" after him.[5]

Caliphate[]

Accession[]

In 714, al-Walid, encouraged or supported by al-Hajjaj, attempted to install his son Abd al-Aziz as his successor, voiding the arrangements set by Abd al-Malik, which made Sulayman heir apparent.[46][47] According to the historian (d. 878), al-Walid offered Sulayman generous financial incentives to agree to the change, but he refused.[46] Al-Walid, nonetheless, issued requests to his provincial governors to recognize Abd al-Aziz, but only received favorable responses from al-Hajjaj and Qutayba ibn Muslim, the governor of Khurasan and conqueror of Transoxiana.[46] An adviser of al-Walid, Abbad ibn Ziyad, counseled the Caliph to pressure Sulayman by summoning him to the Caliph's court in Damascus, and then, after Sulayman stalled in his response, to mobilize his shurta (elite guard) and move against Sulayman in Ramla.[46] Al-Walid died shortly after, on 24 February 715.[1] Sulayman received the news at his estate in al-Sab' (Bayt Jibrin),[48] and acceded to the caliphate unopposed.[46]

Sulayman received oaths of allegiance in Ramla,[49] and in Damascus during his only recorded visit to that city.[5] He continued to govern from Palestine, where he "was much beloved", according to the historian Julius Wellhausen, instead of Damascus,[50] the Umayyads' traditional administrative capital.[5] The historian Reinhard Eisener asserted that the medieval "Syrian sources prove he obviously chose Jerusalem as his principal seat of government",[1] while Wellhausen and the historian Hugh N. Kennedy held that he remained in Ramla.[51]

Provincial politics[]

In his first year in office, Sulayman replaced most of al-Walid's and al-Hajjaj's provincial appointees with governors loyal to him.[1][52] It is unclear whether these changes were the result of resentment and suspicion toward previous opponents of his accession, a means to ensure control over the provinces by appointing loyal officials, or a policy to end the rule of strong, old-established governors.[1] While Eisener argued Sulayman's "choice of governors does not give the impression of bias" toward the Yaman faction,[1] Kennedy asserted that the Caliph's reign marked the political comeback of the Yaman and "reflected his Yamani leanings".[17] One of his immediate decisions was to install his confidant, Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, as governor of Iraq.[51] According to the historian Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban, Sulayman considered Yazid to be his "own al-Hajjaj".[53] Yazid acted with a staunch preference for the Yaman, but according to Wellhausen, there is no indication that Sulayman favored one faction over the other.[54] Wellhausen held that Sulayman, from the time he was governor of Palestine, "may have been persuaded" that the rule of al-Hajjaj engendered hatred among the Iraqis toward the Umayyads rather than fostering their loyalty.[55] Sulayman thus opposed him and his influence and deposed his appointees and allies, not because of their Qaysi affiliation, but because of their personal connection with al-Hajjaj.[55] Sulayman kept close ties with the Qaysi troops of the Jazira.[56]

A protege of al-Hajjaj, Qutayba ibn Muslim, whose relations with Sulayman had been antagonistic, was confirmed in his post by the Caliph, but remained wary that his dismissal was pending.[57] At the time of Sulayman's accession, he had been leading his troops on an expedition toward the Jaxartes valley in Transoxiana. While stopping in Ferghana, he declared a rebellion against Sulayman, but most of his troops, exhausted by the constant campaigns into distant lands, turned against him.[57] Qutayba was killed by an army faction led by in August 715.[1] Waki declared himself governor of Khurasan, and was confirmed by Sulayman, but the latter restricted his authority to military affairs.[57] Sulayman was concerned that Waki's nomination by the tribal factions of the Khurasani army (rather than by his own initiative) would lead to instability in the province.[58] Meanwhile, al-Hajjaj's kinsman and leader of the conquest of Sind, Muhammad ibn Qasim, did not revolt against Sulayman, but was nonetheless dismissed, summoned to Wasit, and tortured to death.[59]

Waki's provisional governorship lasted nine months,[20] ending in mid-716.[57] Yazid had persuaded Sulayman that Waki was a troublesome Bedouin (Arab nomad) lacking administrative qualities.[20] Khurasan, along with the other eastern parts of the Caliphate, were attached to Yazid's Iraqi governorship.[1] The Caliph directed Yazid to relocate to Khurasan and leave lieutenant governors in the Iraqi garrison towns of Kufa, Basra and Wasit, while entrusting Iraq's fiscal affairs to his own appointee, a mawla (pl. mawali; non-Arab freedman or client) with lengthy experience in the province, Salih ibn Abd al-Rahman.[60]

Between 715 and 716, Sulayman dismissed Khalid ibn Abdallah al-Qasri and Uthman ibn Hayyan al-Murri, the respective governors of Mecca and Medina, both of whom owed their appointments to al-Hajjaj.[59] Al-Qasri, later considered a champion of the Yaman,[55] was replaced by an Umayyad family member, Abd al-Aziz ibn Abdallah.[1]

In the west, Sulayman dismissed Musa ibn Nusayr, the Yamani-affiliated governor of Ifriqiya and conqueror of Hispania (al-Andalus), and his son Abd al-Aziz, the governor of al-Andalus.[1][55][61] Musa was imprisoned by Sulayman upon his accession and Abd al-Aziz was assassinated on Sulayman's orders in March 716. The assassination order was carried out by some of the leading Arab commanders in al-Andalus, including Abd al-Aziz's top lieutenant Habib ibn Abi Ubayd al-Fihri.[62] Al-Tabari held that Habib delivered Abd al-Aziz's head to the Caliph.[63] Sulayman installed a mawlā of the Quraysh in place of Musa, and under his order, the new governor confiscated the wealth of Musa's family in Ifriqiya and had them tortured and killed.[64] Musa had a history of embezzling funds during his career and Sulayman extorted considerable sums from him during his imprisonment.[65]

War efforts[]

Although he largely replaced their governors, Sulayman maintained his predecessors' militarist policies.[1] Nonetheless, during his relatively short reign, the territorial expansion of the Caliphate that occurred under al-Walid virtually came to a halt.[1]

Transoxiana[]

On the eastern front, in Transoxiana, further conquests were not achieved for a quarter century after Qutayba's death, during which time the Arabs began to lose territory in the region.[66] Sulayman ordered the withdrawal of the Khurasani army from Ferghana to Merv, and its subsequent disbandment.[57] No military activity was carried out under Waki. Under Yazid's deputy in Transoxiana, his son , expeditions were limited to summertime raids against Sogdian villages.[66] The historian H. A. R. Gibb attributed the Arab military regression in Transoxiana to the void in leadership and organization left by Qutayba's death.[66] Eisener partly attributed it to more effective resistance along the frontiers.[1] The halt in the conquests was not an indication that "the impulse of expansion and conquest slackened" under Sulayman, according to Eisener.[1]

Jurjan and Tabaristan[]

In 716, Yazid attempted to conquer the principalities of Jurjan and Tabaristan, located along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. Ruled by local Iranian dynasties and shielded by the Alborz Mountains, these regions had remained largely independent of Muslim rule, despite repeated attempts to subdue them.[67] The campaign lasted for four months and involved a 100,000-strong army derived from the garrisons of Kufa, Basra, Rayy, Merv and Syria.[1][68] It marked the first deployment of Syrian troops, the elite military faction of the Caliphate, to Khurasan.[69][70] Yazid defeated the Chöl Turks north of the river Atrek, and secured control of Jurjan by founding a city there (modern Gonbad-e Kavus).[71] In a letter, Yazid congratulated Sulayman on the conquests of the two territories, which had eluded previous caliphs until "God made this conquest on behalf" of Sulayman.[72] Yazid's initial success was reversed by Tabaristan's ruler, Farrukhan the Great, and his coalition from neighboring Daylam, Gilan, and Jurjan in later confrontations that year. Afterward, Yazid withdrew Muslim troops from the region in return for a tributary arrangement with Farrukhan.[73] Tabaristan remained independent of Arab rule until 760, when it was conquered by the Abbasids, the successors of the Umayyads,[74][75] but remained a restive province dominated by local dynasts.[76]

Siege of Constantinople[]

The Caliph's principal military focus was the perennial war with Byzantium,[51] which was not only the largest, richest, and strongest of the Caliphate's enemies, but also directly adjacent to Syria, the center of Umayyad power.[77] The Umayyads' first attack on the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, under Mu'awiya I had failed.[78][b] Nevertheless, from 692 onwards, the Umayyads had been on the offensive, secured control of Armenia and the Caucasian principalities, and gradually encroached upon the borderlands of the empire. Umayyad generals, often members of the ruling family, raided Byzantine territory every year, capturing towns and fortresses.[80][81] Aided by a prolonged period of instability in Byzantium,[80][82] by 712, the Byzantine defensive system began to show signs of collapse, as Arab raids penetrated ever deeper into Asia Minor.[83][84]

Following the death of al-Walid I, Sulayman took up the project to capture Constantinople with increased vigor.[85] In late 716, upon returning from the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Sulayman encamped and mobilized his army in Dabiq in northern Syria.[1] From there, he oversaw the massive war effort against the Byzantines.[1] Being too ill to lead the campaign in person,[86] he dispatched his half-brother Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik to besiege the Byzantine capital from the land, with orders to remain until the city was conquered or he was recalled by the Caliph.[87] Already from early 716, the Arab commander Umar ibn Hubayra al-Fazari had launched a parallel naval campaign against Constantinople.[1] While many troops were dispatched toward the Byzantine capital, Sulayman appointed his son Dawud to lead a summer campaign against the Byzantine frontier in 717,[88] during which he captured Hisn al-Mar'a ("the Woman's Fortress") near Malatya.[89]

Sulayman's efforts ultimately failed.[1] The Byzantines repulsed the Umayyad fleet from Constantinople in the summer of 717, while Maslama's army maintained its siege of the city.[90] Umayyad fleets sent in the summer of 718 to aid the besiegers were destroyed by the Byzantines, while an Umayyad relief army was routed and repulsed in Anatolia.[91] Having failed in the siege, Maslama's army withdrew from Constantinople in August 718.[92] The massive losses incurred during the campaign led to a partial retrenchment of the Umayyad forces from the captured Byzantine frontier districts,[93][94] but already in 720, Umayyad raids against Byzantium recommenced. Nevertheless, the goal of conquering Constantinople was effectively abandoned, and the frontier between the two empires stabilized along the line of the Taurus and Anti-Taurus Mountains, over which both sides continued to launch regular raids and counter-raids during the next centuries.[95][96]

Death and succession[]

Sulayman died in Dabiq in September 717,[1] and was buried there.[97] The 11th-century Nestorian Christian chronicler Elias of Nisibis dated his death to 20 September or 21 September, while the 8th-century Muslim historian Abu Mikhnaf placed it on 23 September or 24 September.[50] He fell ill after returning from the Friday prayers and died a few days later.[98]

Sulayman designated his eldest son Ayyub as his successor in 715 or 716, after the death of his brother and potential successor, Marwan al-Akbar.[99] The order is partly corroborated by an ode from the contemporary poet Jarir:

The Imam, whose gifts will be hoped for, after the Imam [Sulayman], is the chosen successor, Ayyub ... You [Ayyub] are the successor to the merciful one [Sulayman], the one whom the people who recite the Psalms recognize, the one whose name is inscribed in the Torah.[99][c]

But Ayyub died in early 717,[100] succumbing to the so-called ta'un al-Ashraf ("plague of the Notables"), that afflicted Syria and Iraq.[101] The same plague may have caused Sulayman's death.[102] On his deathbed, Sulayman considered nominating his other son Dawud, but Raja advised against it, arguing that Dawud was away fighting in Constantinople and that it was unclear if he was still alive.[98] Raja counseled Sulayman to choose his paternal cousin and adviser, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, describing him as a "worthy, excellent man and a sincere Muslim".[98] To avoid potential intra-dynastic strife between Umar and Sulayman's brothers, Yazid ibn Abd al-Malik was appointed Umar's successor.[98] Sulayman's nomination of Umar over his own brothers defied the general assumptions among the Umayyad family that the office of the caliph would be restricted to the household of Abd al-Malik.[103] Raja was chosen to execute Sulayman's will and secured allegiance to Umar from the Caliph's brothers by threatening them with the use of force, following their protestations at being bypassed.[104] According to Eisener, Raja's personal connections to the traditional Muslim reports about Sulayman's nomination of Umar render Raja's role in the succession arrangements as "likely ... exaggerated".[100] According to Shaban, Sulayman nominated Umar because he was the contender "most sympathetic to his policies".[103]

Assessment[]

According to Eisener, it is challenging "to form an appropriate picture of Sulayman's reign", due to its short duration.[1] Shaban held that Sulayman's short rule would "permit more than one interpretation", which is the reason "he is such an ambiguous figure for the historian."[103] Shaban has noted that the "importance of Sulayman's reign does not seem to have been realized" due to the medieval sources' "overwhelming emphasis" on the reign of his successor, Umar II.[105] While Shaban and Kennedy have emphasized Sulayman's championing of the Yaman faction and opposition to the Qays,[103] Eisener has viewed his provincial and military appointments as motivated by a desire to consolidate his control over the Caliphate by installing loyalists in positions of power, factional affiliations notwithstanding.[1] Eisener and Shaban have noted that Sulayman generally maintained the expansionist policies of al-Walid and Abd al-Malik.[1][103]

Shaban has highlighted Sulayman's attempts to further integrate the mawali into the military hierarchy.[103] The historian Patricia Crone has rejected that Sulayman oversaw any policy change regarding their integration.[106] Several Islamic traditional sources credited Sulayman for reversing al-Hajjaj's measures against non-Arab, Muslim converts by allowing the return to Basra of either the urban mawali who had supported the anti-Umayyad revolt of Ibn al-Ash'ath in 700–701, or the Iraqi peasants who converted to Islam and moved to Basra to avoid the jizya (poll tax designated for non-Muslims). Crone has viewed the traditional accounts of Sulayman's policies regarding the runaway peasant converts as "badly attested".[107]

In the panegyrics of Sulayman's contemporary poets, al-Farazdaq and Jarir, Sulayman is viewed in messianic terms as the Mahdi ("rightly guided one") sent to restore justice after a period of oppression.[100][108] Al-Farazdaq praised Sulayman for addressing all grievances and heralded him as the one "predicted by priests and rabbis".[108] The messianic views of Sulayman may have been connected to the approaching centennial of the Hegira and the associated Muslim hopes for the conquest of Constantinople during his reign.[100] Several hadiths (sayings or traditions attributed to Muhammad) associated the conquest of the city with the Mahdi and Sulayman entered the role in his attempt to conquer it.[109] "Sensibly", according to Crone, Sulayman did not publicly reference the widespread belief among Muslims that their community or the world would be destroyed on the centennial.[109]

Sulayman was known to lead a licentious life and the traditional sources hold that he was gluttonous and promiscuous.[110] Al-Ya'qubi described him as "a voracious eater ... attractive and eloquent ... a tall man, white, and with a body that could not bear hunger".[111] He was highly skilled in Arabic oratory.[100] Despite his lifestyle, his political sympathies laid with the pious, chiefly evidenced by his deference to Raja's counsel.[112] He also cultivated ties to the religious opponents of al-Hajjaj in Iraq. He was financially generous toward the Alids (the closest surviving kinsmen of the Islamic prophet Muhammad). He installed as governor of Medina , a member of the city's pious circles, despite his family's role in the fatal rebellion against the early clansman and patron of the Umayyads, Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656), revenge for whom had served as an ideological rallying point and foundational event for the Umayyad dynasty.[113] In contrast to contemporary poetry, the Islamic tradition considers Sulayman to have been cruel and unjust, his overtures to the pious stemming from the guilt of his immoral conduct.[100]

Family[]

Among Sulayman's wives was Umm Aban bint Aban,[114] a granddaughter of al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As, the father of Marwan I; she bore him Ayyub.[99] Another of his Umayyad wives was Umm Yazid, a granddaughter of Caliph Yazid I and sister of the future pretender to the caliphate, Abu Muhammad al-Sufyani.[115] Sulayman was also married to Su'da bint Yahya, a granddaughter of Talha ibn Ubayd Allah, who was a senior companion of Muhammad and an early Muslim leader.[116] His wife A'isha bint Asma bint Abd al-Rahman ibn al-Harith, a member of the prominent Qurayshi clan of Banu Makhzum, bore him two sons.[117] From his umm walad (slave concubine who bore children), Sulayman had his son Dawud.[99]

Sulayman had fourteen sons.[99][d] His eldest surviving son was Muhammad, who was twelve years old at the time of his father's death.[119] Sulayman's sons remained in Palestine and maintained strong ties with the district's Yamani tribal nobility.[120][121] The Arab tribes formed Palestine's garrison and were committed to the family. In 744, they unsuccessfully attempted to install its head, Sulayman's son Yazid, as caliph.[120] Sulayman's son Abd al-Wahid served as governor of Medina and Mecca in 747 for Caliph Marwan II (r. 744–750).[122] Sulayman's property in Palestine remained in his family's possession until the Abbasid Revolution toppled the Umayyad dynasty in 750.[120] Some of his descendants, from the lines of Dawud and Abd al-Wahid, were recorded by the sources living in the Umayyad emirate (756–929) and caliphate of al-Andalus (929–1031).[123]

Notes[]

- ^ There is inconsistency in the sources regarding Sulayman's year of birth, as his age of death is cited in Islamic years as 39, 43, or 45.[2]

- ^ The conventional view of the attacks against Constantinople under Mu'awiya I as a siege is considered to be a "great exaggeration" by the historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship, who held that the Siege of Constantinople under Sulayman and Umar II in 717–718 was "the only such campaign ever undertaken" by the Arabs.[79]

- ^ Ayyub is the Arabic name of the Biblical prophet Job.

- ^ The 9th-century historian al-Ya'qubi mentioned Sulayman's sons Ayyub and Dawud and that he was survived by ten sons: Yazid, al-Qasim, Sa'id, Uthman, Abd Allah or Ubayd Allah, Abd al-Wahid, al-Harith, Amr, Umar and Abd al-Rahman.[118]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Eisener 1997, p. 821.

- ^ Bosworth 1982, p. 45.

- ^ Hinds 1990, p. 118.

- ^ Fück 1965, p. 1023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bosworth 1982, p. 90.

- ^ Kennedy 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Hinds 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 92, 98.

- ^ Crone 1980, p. 125.

- ^ Crone 1980, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Crone 1980, p. 126.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Kennedy 2004, p. 105.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 257.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bosworth 1968, p. 66.

- ^ Hinds 1990, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hinds 1990, p. 162.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Hinds 1990, p. 163, note 540.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bacharach 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharon 1986, p. 799.

- ^ Taxel 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luz 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 37–38, 41.

- ^ Bacharach 1996, pp. 27, 35–36.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Luz 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1005.

- ^ Sharon 1986, p. 800.

- ^ Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1004, note 2278.

- ^ Luz 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Elad 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Bacharach 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hinds 1990, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Shaban 1970, p. 74.

- ^ Lecker 1989, pp. 33, 35.

- ^ Powers 1989, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kennedy 2004, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Shaban 1970, p. 78.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wellhausen 1927, p. 260.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 261.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Shaban 1970, p. 75.

- ^ Shaban 1970, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 258.

- ^ Shaban 1971, p. 128.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 28–30.

- ^ James 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Powers 1989, p. 30.

- ^ Crone 1994, pp. 18, 21, note 97.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 21, note 97.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gibb 1923, p. 54.

- ^ Madelung 1975, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 446.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 198.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd (10 November 2011) [1993]. "Dabuyids". Encyclopaedia Iranica (Online).

- ^ Malek 2017, p. 105.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 200.

- ^ Madelung 1975, pp. 200–206.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 104, 117.

- ^ Hinds 1993, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 25–26, 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blankinship 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Haldon 1990, pp. 72, 80.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Haldon 1990, p. 80.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 120–122, 139–140.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Guilland 1959, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Lilie 1976, p. 132.

- ^ Powers 1989, p. 38.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 117–121.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 143–144, 158–162.

- ^ Powers 1989, p. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Powers 1989, p. 70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bosworth 1982, p. 93.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Eisener 1997, p. 822.

- ^ Dols 1974, p. 379.

- ^ Dols 1974, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Shaban 1971, p. 130.

- ^ Shaban 1971, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Shaban 1970, p. 76.

- ^ Crone 1994, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Crone 1994, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crone 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crone 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 262.

- ^ Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1012.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 264.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Robinson 2020, p. 145.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 93.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1013.

- ^ Powers 1989, p. 71, note 250.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bosworth 1982, p. 92.

- ^ Hillenbrand 1989, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 92.

- ^ Uzquiza Bartolomé 1994, p. 459.

Bibliography[]

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage". Muqarnas Online. 13: 27–44. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000355. ISSN 2211-8993. JSTOR 1523250. (registration required)

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968). Sīstān under the Arabs: From the Islamic Conquest to the Rise of the Ṣaffārids (30–250, 651–864). Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. ISBN 9788863231243. OCLC 956878036.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1982). Medieval Arabic Culture and Administration. London: Variorum. ISBN 978-0-86078-113-4.

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Crone, Patricia (1994). "Were the Qays and Yemen of the Umayyad Period Political Parties?". Der Islam. 71: 1–57. doi:10.1515/islm.1994.71.1.1. S2CID 154370527.

- Crone, Patricia (2004). Gods Rule: Government and Islam. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13290-9.

- Dols, M. W. (July–September 1974). "Plague in Early Islamic History". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 94 (3): 371–383. doi:10.2307/600071. JSTOR 600071.

- Eisener, R. (1997). "Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 821–822. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Elad, Amikam (1999). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10010-7.

- Fück, J. W. (1965). "Ghaṭafān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1023–1024. OCLC 495469475.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1923). The Arab Conquests in Central Asia. London: The Royal Asiatic Society. OCLC 499987512.

- Gordon, Matthew S.; Robinson, Chase F.; Rowson, Everett K.; Fishbein, Michael (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Guilland, Rodolphe (1959). "L'Expedition de Maslama contre Constantinople (717–718)". Études byzantines (in French). Paris: Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Paris: 109–133. OCLC 603552986.

- Haldon, John F. (1990). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31917-1.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hillenbrand, Carole, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVI: The Waning of the Umayyad Caliphate: Prelude to Revolution, A.D. 738–744/A.H. 121–126. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.

- Hinds, Martin, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIII: The Zenith of the Marwānid House: The Last Years of ʿAbd al-Malik and the Caliphate of al-Walīd, A.D. 700–715/A.H. 81–95. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-721-1.

- Hinds, M. (1993). "Muʿāwiya I b. Abī Sufyān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 263–268. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- James, David (2009). Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47552-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2002). "Al-Walīd (I)". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Lecker, Michael (1989). "The Estates of 'Amr b. al-'Āṣ in Palestine: Notes on a New Negev Arabic Inscription". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 52 (1): 24–37. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00023041. JSTOR 617911. (registration required)

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München.

- Luz, Nimrod (April 1997). "The Construction of an Islamic City in Palestine. The Case of Umayyad al-Ramla". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 7 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008300. JSTOR 25183294.

- Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Malek, Hodge (2017). "Tabaristan during the 'Abbasid Period: The Overlapping Coinage of the Governors and other Officials (144–178H)". In Faghfoury, Mostafa (ed.). Iranian Numismatic Studies: A Volume in Honor of Stephen Album. Lancaster and London: Classical Numismatic Group. pp. 71–78. ISBN 978-0-9837-6522-6.

- Powers, Stephan, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIV: The Empire in Transition: The Caliphates of Sulaymān, ʿUmar, and Yazīd, A.D. 715–724/A.H. 96–105. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0072-2.

- Robinson, Majied (2020). Marriage in the Tribe of Muhammad: A Statistical Study of Early Arabic Genealogical Literature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-062416-8.

- Shaban, M. A. (1970). The Abbasid Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29534-5.

- Shaban, M. A. (1971). Islamic History: Volume 1, AD 600–750 (AH 132): A New Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08137-5.

- Sharon, M. (1986). "Ludd". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 798–803. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Taxel, Itamar (May 2013). "Rural Settlement Processes in Central Palestine, ca. 640–800 C.E.: The Ramla-Yavneh Region as a Case Study". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 369 (369): 157–199. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.369.0157. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.369.0157. S2CID 163507411.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Uzquiza Bartolomé, Aránzazu (1994). "Otros Linajes Omeyas en al-Andalus". In Marín, Manuela (ed.). Estudios onomástico-biográficos de Al-Andalus: V (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 445–462. ISBN 84-00-07415-7.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

- Williams, John Alden, ed. (1985). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVII: The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, A.D. 743–750/A.H. 126–132. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-884-4.

- 670s births

- 717 deaths

- 8th-century deaths from plague (disease)

- 8th-century Umayyad caliphs

- City founders

- History of Ramla

- People from Medina