Talaat Pasha

Mehmed Talaat Pasha | |

|---|---|

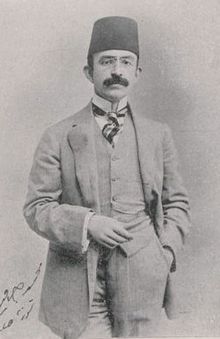

Talaat in exile in Berlin | |

| Grand Vizier | |

| In office 4 February 1917 – 8 October 1918 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed VI Mehmed V |

| Preceded by | Said Halim Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Izzet Pasha |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 12 June 1913 – 8 October 1918 | |

| Grand Vizier | Himself Said Halim Pasha |

| Preceded by | Mehmed Adil |

| Succeeded by | Mustafa Arif |

| In office August 1909 – March 1911 | |

| Grand Vizier | İbrahim Hakkı Pasha Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha |

| Preceded by | Mehmed Ferid Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Halil Menteşe |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office November 1914 – 4 February 1917 | |

| Grand Vizier | Said Halim Pasha |

| Preceded by | Abdurrahman Vefik Sayın |

| Succeeded by | Mehmed Cavid |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 17 December 1908 – 8 October 1918 | |

| Constituency | Adrianople (1908, 1912, 1914) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 September 1874 Kırcaali, Ottoman Empire (now Kardzhali, Bulgaria) |

| Died | 15 March 1921 (aged 46) Berlin, Germany |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Monument of Liberty, Istanbul |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Political party | Union and Progress Party |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Young Turk Revolution 31 March Incident World War I Armenian-Azerbaijani War Russian Civil War |

| Criminal charge | First degree mass murder[1] |

| Trial | Ottoman Special Military Tribunal |

| Penalty | Death (in absentia) |

| Details | |

| Target(s) | Ottoman Armenians |

| Killed | Around 1 million |

Mehmed Talaat[a] (1 September 1874 – 15 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha,[b] was an Ottoman Turkish politician and convicted war criminal of the late Ottoman Empire who served as its de facto leader from 1913 to 1918.[2] Talaat Pasha was the leader of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which operated a one party dictatorship and followed an ideology known as İttihadism. The Armenian genocide and other ethnic cleansing operations were undertaken during his time as Minister of Interior Affairs during World War I. Following the Mudros Armistice, Talaat fled to Germany in exile, where he was assassinated.

Born in Kırcaali (Kardzhali), Adrianople (Edirne) Vilayet, Mehmed Talaat grew up to despise Abdul Hamid II's autocracy. He became an early member of the CUP, a secret revolutionary Young Turk organization, and over time became its leader. After the CUP succeeded in restoring the constitution and parliament in the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, Talaat was elected as a deputy from Adrianople (Edirne) to the Chamber of Deputies and later became Minister of the Interior. Talaat played an important role in the downfall of Abdul Hamid the next year during the 31 March Incident by organizing a counter government.

After the 1913 coup and Mahmud Şevket Pasha's assassination, the Empire was ruled by the CUP in a dictatorship, whose leaders were the triumvirate of Talaat, İsmail Enver, and Ahmed Cemal (known as the Three Pashas), of whom Talaat was politically most powerful. Talaat and Enver Pasha were influential bringing the Ottoman Empire into the First World War. During World War I, Talaat ordered as Interior Minister on 24 April 1915 the arrest and deportation of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople (now Istanbul), most of them being ultimately murdered, and on 30 May 1915 requested the Tehcir Law (Temporary Deportation Law); these events initiated the Armenian genocide. He is widely considered the main perpetrator of the genocide,[3][4][5][6][7] and is thus held responsible for the death of around 1 million Armenians. Talaat Pasha became Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) in 1917 and oversaw the introduction of many modernizing social reforms, which Mustafa Kemal Atatürk would later build upon.[8]

With the fall of the CUP after the Empire's surrender in World War I, on the night of 2–3 November 1918, Talaat Pasha and other members of the fled the Ottoman Empire (Talaat ended up in Berlin, Germany). The Ottoman Special Military Tribunal convicted Talaat and sentenced him to death in absentia for subverting the constitution, profiteering from the war, and organizing massecres against Greeks and Armenians. In exile, Talaat lobbied for supporting the Turkish Nationalists in Turkey's War of Independence. Talaat was assassinated in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, as part of Operation Nemesis.[8]

In Turkey, Talaat Pasha is viewed as a "great statesman, a skillful revolutionary, and a farsighted founding father", and many schools, streets, and mosques are also named after him.[9] Biographer Hans-Lukas Kieser asserts that Talaat Pasha "...in the historical area of larger Europe, opens the age of extremes and the Europe of the dictators."[10]

Early life: 1874–1908[]

Childhood[]

Mehmed Talaat was born in 1874 in Kırcaali town of Adrianople (Edirne) Vilayet into a middle-class family[11] of Romani[12][13][14] and Pomak descent.[15][16][17] His father, Ahmet Vasıf, was a kadı from a village in the mountainous southeastern corner of present-day Bulgaria.[7] His mother's name was Hürmüz. Talaat also had two sisters.[18] Talaat's family fled from the Russian army in 1877 from Adrianople for Constantinople, but returned to a year later after the war. His father passed away when Talaat was eleven years old.[18]

Talaat had a powerful build and a dark complexion.[19] His manners were gruff, which caused him to be expelled from the military secondary school at the age of sixteen without a certificate after a conflict with his teacher.[11] Without earning a degree, he joined the staff of the telegraph company as a postal clerk in Adrianople to provide for his family. His salary was not high, so he worked after hours as a Turkish language teacher in the Alliance Israelite School which served the Jewish community of Adrianople.[19] At the age of 21 Talaat was involved in a love affair with the daughter of the Jewish headmaster for whom he worked.[20]

Early activism[]

The Ottoman Empire was ruled by Abdul Hamid II, who ran a modern autocracy, complete with a secret police, mass surveillance, and censorship. This autocracy, contemperarily known as İstibdâd (the despotism), in turn produced a culture of suspicion as well as a spirit of clandestine rebellion in most Ottoman citizens, young Talaat included. Talaat was caught sending a telegram saying "Things are going well. I'll soon reach my goal." He claimed that the message in question was to his dalliance, who defended him. With two of his friends from the post office, he was charged with tampering with the official telegraph and was arrested in 1893.[20]

Talaat was an early member of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a secret revolutionary Young Turk organization which was agitating against Abdul Hamid's autocracy. In 1896 he was imprisoned for having been part of a cell belonging to the CUP together with his brother-in-law .[21] Sentenced to two years in jail, he was pardoned[19] but exiled to Selanik (Thessaloniki), where he became a postal clerk in July 1898.[21] Between 1898 and 1908 he served as a postman on the staff of the Selanik Post Office, during which he continued his revolutionary activities in secret. He was promoted to the head of the postal clerks in April 1903, following which he could afford to bring his mother and sisters to Selanik.[22] Talaat met then economics professor, later friend and CUP Minister of Finance Mehmed Cavid Bey in , where he took classes to supplement his lackluster education.[21] He joined the Salonica Freemason lodge Macedonia Risorta in 1903.[21]

In September 1906, the (OFS) was formed as another secret Young Turk organization based in Selanik. The founders of the OFS included Talaat, the CUP's future general secretary Dr. Midhat Şükrü, Mustafa Rahmi, and .[23] Many officers of the Third Army were recruited into the OFS, including the future heros of the revolution Ahmed Niyazi and İsmail Enver. Under Talaat's initiative, the Selanik-based OFS merged with Rıza's Paris-based CUP in September 1907, and the group became the internal center of the CUP in the Ottoman Empire.[23] After the revolution, Talaat's more radical and militant internal CUP cadre would see themselves supplant Rıza's leadership of his network of exiles. For now this merger transformed the committee from an intellectual opposition group into a sort of clandestine paramilitary.[24]

Rise to power: 1908–1913[]

Young Turk Revolution and aftermath[]

The Unionists found themselves at the behest of a spontaneous revolution in 1908, which started with Niyazi and Enver's flight into the Albanian hinterlands. Talaat's role during the Young Turk Revolution was to organize a plot to assassinate the garrison commander of Selanik, Ömer Nazım, who was a Hamidian loyalist and spy master of the area. Nazım survived the hired Fedai with injury, but the incident, as well as other assassinations carried out by the CUP during the revolution, intimidated the Hamidian establishment enough to reopen the parliament and reinstate the constitution.[25] In the following election, Talaat was elected as a deputy for Adrianople in the Ottoman Parliament, and then the parliament's vice-president.[26]

A year later in the 31 March Incident, what started out as an anti-Unionist demonstration in the capital quickly turned into an anticonstitutionalist-monarchist counter revolution where Abdul Hamid attempted to reestablish his autocracy. Khachatur Malumian, leader of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), hid Talaat and Dr. Mehmet Nazım in his house during mob violence targeting deputies of the parliament.[27] Three days later, Talaat and 100 MPs escaped Constantinople for Ayastefanos (Yeşilköy) to organize a separate national assembly () from the volatile situation in Constantinople.[28] Relief came in the form of pro-constitutionalist forces known as the Action Army, lead by Mahmud Şevket Pasha which stopped in Ayastefanos before marching on the capital; it was secretly agreed there that Abdul Hamid would be replaced by his brother, Mehmed Reşad.[28] After the reactionary revolt was crushed, Talaat was able to bully the sheykhulislam Sahip Molla to get a fatwa for Abdul Hamid's deposition.[29] With the fatwa, the parliament voted to depose Abdul Hamid II, and Mehmed V took his place.

Talaat was also able to convince Ahmed Tevfik Pasha, who replaced prime minister (Grand Vizier) Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha at Abdul Hamid's request during the 31 March Crisis, to step down and return Hilmi Pasha to the premisership.[29] He later replaced Ferid Pasha as Minister of the Interior in Hilmi Pasha's cabinet in August 1909, becoming the second Unionist with a cabinet position (first being Cavid as Finance Minister). Talaat continued Hamidian era anti-Zionist restrictions in Ottoman Palestine,[30] as well as enforce imperial rule in revolting provinces like Albania and Yemen.[31] He stepped down in March 1911 for his friend Halil Bey.[32] For a short time Talaat was in January 1912.[33]

Crisis for the CUP[]

In the 1912 election known as the "election of clubs", the CUP won a lopsided victory known due to widespread employment of electoral fraud and violence. The opposition Freedom and Accord Party organized a group in the military known as the Savior Officers to bring down the CUP controlled legislature and call for new elections. Talaat urged for Şevket Pasha, who was appointed Minister of War after the 31 March Incident, to resign as in the lead-up to the 1912 coup d'état, something he wrote that he regretted once Şevket Pasha did so in support of the Savior Officers.[34] The pro-Unionist Grand Vizier Mehmed Said Pasha had to acquiesce to the Savior Officers demands. Without allies, and the parliament shuttered, new elections were called for the autumn. It was no longer safe for Unionists to be in the open, and it was plausible that the CUP would be shut down by the government. Talaat had to once again lay low, hiding with Midhat Şükrü, Hasan Tahsin, and Cemal Azmi in Tahsin's brother-in-law's house.[35] By 1912 Talaat definitely abandoned the belief that constitutionalism and rule of law could unite the multi-ethnic and fragmented "Ottoman nation", which was the original raison d'être of the Young Turks, and turned to more radical politics.[36] Talaat and other high ranking CUP leaders organized and gave speeches in a pro-war rally against the Balkan nations in Sultanahmet Square before the Balkan Wars broke out.[37]

The Savior Officer-backed government of Ahmed Muhtar Pasha fell soon after when the Balkan League achieved decisive victory over the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War. The CUP's headquarters in Selanik had to be relocated to Constantinople when the city fell to Greece, while Talaat's hometown of Adrianople was besieged by the Bulgarians. The scheduled elections had to be canceled, and Kâmil Pasha's government started peace negotiations with the Balkan League in December. Following rumors that the government was willing to surrender Adrianople which was still under siege, Talaat and Enver started plotting a coup. The coup launched in January 1913, known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte, succeeded in overthrowing the government, with Kâmil Pasha and his cabinet resigning for Mahmud Şevket Pasha's government which this time included the CUP. Mutual distrust between Şevket Pasha and Talaat meant he couldn't yet enter the cabinet, so he employed politics to stay influential.[38] He urged for the Empire to continue fighting in the First Balkan War to relieve Adrianople, as well as order many arrests against Freedom and Accord members and journalists in the subsequent state of emergency.[39] However, with demands from the great powers to surrender Adrianople and a deteriorating military situation, Şevket Pasha and the CUP finally acknowledged defeat.

Union and Progress regime: 1913–1918[]

Consolidating power[]

With Şevket Pasha out of the picture due to his assassination in July 1913, the CUP established a one-party state in the Ottoman Empire. Talaat returned as interior minister in Said Halim Pasha's cabinet, who was a puppet of the committee. Talaat kept this post until the CUP's fall from power following the Ottoman Empire's surrender in World War I in 1918. Talaat, with Enver and commandant Ahmet Cemal, formed a group later known as the Three Pashas. These men formed the triumvirate that ran the Ottoman government until the end of World War I in October 1918. However Hans-Lukas Kieser writes that this state of rule by triumvirate was only accurate for the years 1913–1914. Thereafter he asserts Talaat was the sole dictator of the Ottoman Empire, especially once he became Grand Vizier in 1917.[40] Kieser also asserts Talaat's Ottoman Empire was not a totalitarian state, but a balance of many factions through kickbacks and corruption. Strong governors had much maneuverability to themselves, provided they execute Talaat and the central committee's new Turkification programmes.[41]

That summer came Bulgaria's attack on Greece and Serbia, starting the Second Balkan War. Talaat was able to procure an important loan from the Régie des Tabacs to ensure success in retaking Adrianople.[42] The Ottomans soon joined the war, retaking the city even though the great powers had forced the Ottomans to surrender Adrianople only months earlier. This was a failure of diplomacy by the great powers; for Talaat and the CUP, this moment made them learn to not take international diplomacy seriously if the situation on the ground reflected otherwise.[43] Talaat lead the negotiations with Bulgaria in the Istanbul conference, which resulted in a population exchange and formalizing Ottoman reassertion of sovereignty over Adrianople.[44] Talaat would negotiate another peace with Greece too.[44] This peace was very tenuous however, as Talaat, Enver, and Mahmud Celal (Bayar), secretary of the local CUP branch, organized the deportations of Rûm in the Smyrna Vilayet, which almost started a war with Greece.[45] Upon Mehmed V learning of the deportations via the Rûm Patriarchate, Talaat was confronted by the sultan, but insisted that the stories of persecution of Rûm were fabricated by the Empire's enemies.[46]

Between 1911 and 1914, the Ottoman Empire negotiated with the European powers and the ARF on reform in the East. Talaat attended multiple meetings with leading Armenian politicians Krikor Zohrab, Armen Garo, , and Vartkes Serengülian, however lack of trust between the old allies of the committee and the ARF and growing radicalism within the CUP slowed negotiations.[47] Under overwhelming diplomatic pressure, a reform package was finally produced in December 1914, but it would be soon terminated under wartime conditions and an about-face by the committee on the Armenian Question. On the September 6, Talaat Pasha sent a telegram to the governors of Hüdâvendigâr (modern Bursa), Izmit, Canik, Edirne, Adana, Aleppo, Erzurum, Bitlis, Van, Sivas, Mamuretülaziz (modern Elazığ), and Diyarbakır to prepare for the arrests of Ottoman Armenian citizens.[48] Armenians and Assyrians within the Empire also started organising themselves into militias to protect themselves as the Special Organisation, a CUP paramilitary, started harassing them.[49]

Entering World War I[]

Throughout the Second Constitutional Era, the Ottoman Empire was diplomatically isolated, which it payed dearly for through territorial losses in the Balkans. Therefore, on May 9, Talaat along with Ahmet Izzet Pasha traveled to Livadiya, Crimia, to meet with Czar Nicholas II and foreign minister Sergei Sazanov, and proposed an alliance with Russia, which ended up falling through.[50] Talaat, Enver, and Halil were successful in securing a secret alliance with Germany during the July Crisis. Following the sale of the Goeben and Breslau to the Ottoman Empire, the three convinced Cemal Pasha to agree to a naval strike against Russia.[36] The resulting declarations of war prompted Cavid's resignation as finance minister, which temporarily factionalized the committee and saddened Talaat.[51] He also became finance minister in Cavid's place.

With the expectation that the new war would free the Empire of its constraints on its sovereignty by the great powers, Talaat went ahead with accomplishing major goals of the CUP; unilaterally abolishing the centuries-old Capitulations, prohibiting foreign postal services, terminating Lebanon's autonomy, and suspending the reform package for the Eastern Anatolian provinces that had been in effect for just seven months. This unilateral action prompted a joyous rally in Sultanahmet Square.[52]

Talaat and his CUP hoped to save the Ottoman Empire by quickly and decisively establishing Turan by defeating Russia and Britain in Egypt. Enver Pasha's decisive defeat in Sarıkamış and Cemal Pasha's failure to take Suez meant Talaat had to come to terms with the reality on the ground, which made him fall into a depression.[53] He worked to keep moral afloat on the crumbling Caucasian front by relaying false information of successes in wars in the Balkans which weren't even happening.[54]

Eastern Holocaust[]

A report presented to Talaat and Cevdet Bey (governor of Van Vilayet) by ARF members Arshak Vramian and Vahan Papazian on atrocities committed by the Special Organisation against Armenians in Van created more friction between the two organisations. However, the Unionists were still not yet confident enough to purge Armenians from politics or pursue policies of ethnic engineering.[55] Victory of the defence of the Bosphorus on 18 March though galvanized Talaat, and he decided to take action by starting the machinations of the destruction of Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire.[56]

On 24 April 1915, Talaat issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople, including politicians, clergymen, physicians, authors, journalists, lawyers, and teachers, the majority of whom were eventually murdered, including his colleagues Zohrab and Serengülian.[57] Although the mass killings of Armenian civilians had begun in the vilayet of Van several weeks earlier, these mass arrests in Constantinople are considered by many commentators to be the start of the Armenian genocide.[57][58][59]

Talaat then issued the order for the Tehcir Law of 1 June 1915 to 8 February 1916 that allowed for the mass deportation of Armenians, a principal means of carrying out what is now recognized as a genocide against Armenians.[60] The deportees did not receive any humanitarian assistance and there is no evidence that the Ottoman government provided the extensive facilities and supplies that would have been necessary to sustain the life of hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees during their forced march to the Syrian Desert or after.[59][61] Meanwhile, the deportees were subject to periodic rape and massacre, often the result of direct orders by the CUP. Talaat, who was a telegraph operator from a young age, had installed a telegraph machine in his own home and sent "sensitive" telegrams during the course of the deportations.[62][63] This was confirmed by Talaat's wife , who stated that she often saw him using it to give direct orders to what she believed were provincial governors.[64]

Talaat believed Armenian deportation avenged the Muslim expulsions of the Balkan Wars.[65] In May 1915, he gave an interview to the , Talaat stated:

We have been blamed for not making a distinction between guilty and innocent Armenians. [To do so] was impossible. Because of the nature of things, one who was still innocent today could be guilty tomorrow. The concern for the safety of Turkey simply had to silence all other concerns. Our actions were determined by national and historical necessity.[66]

Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. On 2 August 1915, he told the United States ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, Sr. "that our Armenian policy is absolutely fixed and that nothing can change it. We will not have the Armenians anywhere in Anatolia. They can live in the desert but nowhere else." He told him in a later conversation that:

It is no use for you to argue . . . we have already disposed of three quarters of the Armenians; there are none at all left in Bitlis, Van, and Erzeroum. The hatred between the Turks and the Armenians is now so intense that we have got to finish with them. If we don’t, they will plan their revenge.[67]

In another exchange, Talaat demanded from Morgenthau the list of the holders of American insurance policies belonging to Armenians—"they are practically all dead now"—in an effort to appropriate the funds to the state. Morgenthau refused.[68] By the end of the war, the subsequent German ambassador Johann von Bernstorff described his discussion with Talaat: "When I kept on pestering him about the Armenian question, he once said with a smile: 'What on earth do you want? The question is settled, there are no more Armenians'".[69]

The Assyrian Christian community was also targeted by the Unionist government in what is now known as the Seyfo. Talaat ordered the governor of Van to also remove the Assyrian population in Hakkâri, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, however this anti-Assyrian policy couldn't be implemented nationally.[70]

Meanwhile, deportations of the Rûm were put on hold as Germany wished for a Greek ally or neutrality, however for the sake of their alliance, German reaction to the deportations of Armenians was muted. The participation of the Ottoman Empire as an ally against the Entente powers was crucial to German grand strategy in the war, and good relations were needed. Following Russian breakthrough in the Caucasus and signs that Greece would side with the Allied powers after all, the CUP was finally able to resume operations against the Greeks of the empire, and Talaat ordered the deportation of the Pontus Greeks of the Black Sea coast.[71]

Talaat was also a leading force in the Turkification and deportation of Kurds. In May 1916 Talaat demanded Kurds being deported to the western region of Anatolia, and prohibited the resettlement of Kurds to the south in order to prevent Kurds from becoming Arabized.[72] He was a major force behind the policies regarding the resettlement of Kurds and wanted to be informed of whether the Kurds would really be turkified or not and how they got along with the Turkish inhabitants in the areas where they had been resettled too.[73] Talaat outlined that nowhere in the Empire's vilayets should the Kurdish population be more than 5%.[74] To that end, Balkan Muslim and Turkish refugees were also prioritised to be resettled in Urfa, Maraş, and Antep, while some Kurds were deported to Central Anatolia.[72] Kurds were supposed to be resettled in abandoned Armenian property, however negligence by resettlement authorities still resulted in the deaths of many Kurds by famine.[75]

Premiership[]

On 4 February 1917, Talaat finally replaced Said Halim Pasha (a puppet of the committee anyway) by becoming a Pasha and the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire,[76] while also retaining the Ministry of the Interior.[76] On 15 February, Mehmed Talaat Pasha gave a speech to parliament of his program, expressing his and the government's will to pass reforms to bring Ottoman society on par with European civilization. Like first president of the succeeding republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, would later say similarly, Talaat Pasha believed that there was "only one civilization in the world [Europe], [and that Turkey] to be saved, must be joined to civilization." Another point brought up was cracking down on corruption, much of which he created and never followed through with.[77]

Many social reforms were introduced, including modernization of the calendar, employment of women as nurses, charitable organizations, in army shops, and in labor battalions behind the front and new faculties in Istanbul University in architecture, arts, and music. One particular piece of controversial social reform was the 1917 "Temporal Family Law" which was a significant advance in women's rights and secularism in Ottoman matrimonial law. When it came to religious reform, the Koran was translated into (Ottoman) Turkish, and even the conduction of prayers in Turkish in a few select mosques in the capital.[78] These pre-Kemalist secularisation and modernisation reforms paved the way for further and more far reaching reforms by Atatürk's regime. In a play of zugzwang after the Balfour Declaration, Talaat reproached with the Zionist movement, promising to open up Jewish immigration to Jerusalem.[79]

This promise did not reflect ground conditions. Talaat Pasha's first year as Grand Vizier saw the loss of Jerusalem and Baghdad. However territorial loss in the south also coincided with a crushing diplomatic success with the signing of the Brest Litovsk treaty on 10 March 1918, negotiated by only Talaat himself, resulting in the return of Kars, Batumi, and Ardahan to Ottoman rule after their loss forty years ago. Another treaty with the Caucasian states signed in Batum strengthened the Ottoman's position in a future drive on Baku, which was accomplished by September. At the beginning of January 1918 with the Tsarist Army of the Caucasus departing, Talaat had been influential in pursuing an offensive policy, convinced that despite all the pacifist rhetoric coming from Moscow 'the Russian leopard had not changed its spots'. Spring 1918 was the zenith of Talaat Pasha's political career, followed by a slow realization of defeat in WWI over the summer.[80] In a conversation with Cavid, Talaat felt trapped between three "fires": Enver Pasha, who was becoming increasingly erratic and overly optimistic after the breakthrough in the Caucasus; the new sultan Mehmed VI, an anti-Unionist and a stronger personality than his deceased half brother, and Allied armies advancing from the West and the South.[81] In October 1918, the British defeated both Ottoman armies they faced in the Palestinian Front. Simultaneously on the Macedonian front, Bulgaria capitulated to the allies, leaving no sufficient forces to check an advance on the Ottoman capital. With defeat certain (and growing unrest from years of unfettered corruption) Talaat Pasha and his cabinet announced their resignations on 13 October 1918.[82] The new Grand Vizier Ahmed Izzet Pasha and his government capitulated to the Allies and signed Armistice of Mudros on 30 October, but didn't order Talaat's arrest nor order his extradition from Germany until an Istanbul court demanded it.[83]

Exile: 1918–1921[]

Escape to Germany[]

Talaat delivered a farewell speech in the last CUP congress on November 1, and fled the Ottoman capital on a German torpedo boat that night. With Enver, Cemal, Nâzım, and Bahattin Şakir, they landed in Sevastopol, Crimea and scattered from there. Public opinion was shocked by the departure of Talaat Pasha, even though he had been known to turn a blind eye on corrupt ministers appointed because of their associations with the CUP.[84] Talaat Pasha had a reputation for being courageous and patriotic, the type of individual who willingly faced the consequences of his actions.[84]

Talaat along with Nâzım, and Şakir, witnessed key events of the early Weimar Republic, winding up in Berlin on 10 November, a day after Kaiser Wilhelm II fled the city due to the November Revolution. The new chancellor, Friedrich Ebert of the SPD, signed the documents secretly allowing Talaat asylum in Germany, where he settled in a flat at Hardenbergerstrasse 4 (Ernst-Reuter Square), Charlottenburg, under the pseudonym "Ali Sâî". Next to his apartment he founded the "Orient Club" (Şark Kulübesi), where anti-Entente Muslims and European activists met. His wife, Hayriye, joined him in spring 1920.[85] In exile, Talaat cobbled together a coalition of Turkish nationalists, German nationalists, and Bolsheviks to support the Turkish nationalist movement from abroad on behalf of Mustafa Kemal Pasha.[86] Though he was a wanted man in the Ottoman Empire and Britain, Talaat managed to visit Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, Holland, and Denmark, where he lobbied against the new Allied world-order, specifically against their designs on the Ottoman Empire.[87] Questioned whether Talaat would return and join the Turkish National Movement, he declined, arguing that Mustafa Kemal is now the new leader.[88]

After the failure of the Kapp Putsch Talaat spoke in subsequent press conference, where he exclaimed that "A putsch without a cabinet ready at hand was just childish."[89]

Trial and conviction[]

The British government exerted diplomatic pressure on the Ottoman Porte and brought to trial the Ottoman leaders who had held positions of responsibility between 1914 and 1918 for having committed, among other charges, the Armenian Genocide. With the allied occupation of Constantinople, Izzet Pasha resigned. Ahmet Tevfik Pasha took the position of grand vizier the same day that Royal Navy ships entered the Golden Horn. Tevfik Pasha's premiership lasted until 4 March 1919, replaced by Ferid Pasha whose first order was the arrest of leading members of the CUP.[citation needed] Those who were caught were put under arrest at the Bekirağa division and were subsequently exiled to Malta. Courts-martials were organized by Sultan Mehmed VI to punish the CUP for the empire's ill-conceived involvement in World War I.[citation needed]

By January 1919, a report to Sultan Mehmed VI accused over 130 suspects, most of whom were high officials. The indictment accused the main defendants, including Talaat, of being "mired in an unending chain of bloodthirstiness, plunder and abuses". They were accused of deliberately engineering Turkey's entry into the war "by a recourse to a number of vile tricks and deceitful means". They were also accused of "the massacre and destruction of the Armenians" and of trying to "pile up fortunes for themselves" through "the pillage and plunder" of their possessions. The indictment alleged that "The massacre and destruction of the Armenians were the result of decisions by the Central Committee of Ittihadd".[90] The Court released its verdict on 5 July 1919: Talaat, Enver, Cemal, and Dr. Nazım were condemned to death in absentia.[citation needed]

Monitoring by British intelligence[]

The British government continued to monitor Talaat's activities after the war. The British government had intelligence reports indicating that he had gone to Germany, and the British High Commissioner pressured Damat Ferid Pasha and the Sublime Porte to request that Germany extradite him to the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed] Germany was well aware of Talaat's presence but refused to surrender him.[91]

The last official interview Talaat granted was to Aubrey Herbert, a British intelligence agent.[92] During this interview, Talaat maintained at several points that the CUP had always sought British friendship and advice, but claimed that Britain had never replied to such overtures in any meaningful way.[93]

Assassination[]

With most CUP leaders in exile, the ARF organized a plot to assassinate the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide, known as Operation Nemesis. On 15 March 1921 Talaat was assassinated with a single bullet as he came out of his Hardenbergstrasse house to purchase a pair of gloves. His assassin was a Dashnak member from Erzurum named Soghomon Tehlirian, whos entire family was killed during the genocide.[94] Tehlirian admitted to the shooting, but, after a cursory two-day trial, he was found innocent by a German court on grounds of temporary insanity due to the traumatic experience he had gone through during the genocide.[95] Immediately after the assassination, Talaat's friends Nazım and Şakir, who were also staying in the area, received police protection.[96] Şakir would also be assassinated a year later by a Dashnak.

Funeral[]

Initially, Talat's friends hoped he could be buried in Anatolia, but neither the Ottoman government in Constantinople nor the Turkish nationalist movement in Ankara wanted the body; it would be a political liability to associate themselves with the man considered the worst criminal of World War I.[97] Invitations from Hayriye and the Orient Club were sent to Talaat's funeral, and on 19 March, he was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in a well-attended ceremony.[98][96] At 11:00 a.m., prayers led by the imam of the Turkish embassy, Shükri Bey, were held at Talaat's apartment. Afterwards, a large procession accompanied the coffin to Matthäus, where he was interred.[96] Many prominent Germans paid their respects, including former foreign ministers Richard von Kühlmann and Arthur Zimmermann, along with the former head of Deutsche Bank, the ex-director of the Baghdad railway, several military personnel who had served in the Ottoman Empire during the war and August von Platen-Hallermünde, attending on behalf of the exiled Kaiser Wilhelm II.[97] The German foreign office sent a wreath with a ribbon saying, "To a great statesman and a faithful friend."[99][97] Şakir, barely able to maintain his composure, read a funeral oration while the coffin was lowered into the grave, covered in an Ottoman flag.[97] He asserted the assassination was "the consequence of imperialist politics against the Islamic nations".[98]

During World War II, at the request of the Prime Minister of Turkey, Şükrü Saracoğlu,[100] Talaat's remains were disinterred and transported to Turkey, where he received a state funeral on 25 February 1943, attended by German ambassador Franz von Papen, Ahmet Emin Yalman, and Saracoğlu.[101][102][103] With this gesture, Adolf Hitler hoped to secure Turkish support for the Axis.[102] Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın gave the funeral oration as Talaat was buried at the Monument of Liberty, Istanbul, originally dedicated to those who lost their lives during the 31 March Incident.[104] His return to Turkey was welcomed by Turkish society.[105]

Personality and relationships[]

Impressions[]

Many of Talaats contemporaries wrote of his charm but also of a melancholy spirit.[106] Some occasionally noticed his naivety and others commented on his intimidation skills.[107]

His life-long friend Mehmed Cavid wrote of the fall of Talaat and the CUP into a delusional "all or nothing" approach for salvation by war via the July Crisis. Krikor Zohrab wrote "[Talaat was] the foremost partisan of war" for "whom [he] and his disciples, this war was tout ou rien [all or nothing]".[108] Talat's intentional falsehoods were noted by his contemporaries, and even some of his close friends considered him a liar.[109] Hans-Lukas Kieser writes that Talaat was under the influence of the doctors Bahattin Şakir and Mehmed Nazım before 1908, but after late 1909 Talaat had an increased interest in the new Central Committee member Ziya Gökalp and his more revolutionary and Pan-Turkist ideas.[110]

By 1909, Louis Rambert, director of the Régie, wrote that Talaat was "the acknowledged head of the Committee of Union and Progress and the Young Turks."[111] The ARF viewed Talaat a part of the CUP's left-wing faction.[112] Zionist leader Alfred Nossig described Mehmed Talaat as "The strongest man of Young Turkey," a "man of will," a "unique and outstanding talent of statesmanship" who dominates "the whole state machine." Whereas "the sultan is a constitutional ruler, Talaat is an autocratic sultan." He called Talaat "the Turkish Bismarck" upon his becoming Grand Vizier, a title which German jounralist and companion Ernst Jäckh affirmed.[113][114] Others drew similarities between Talaat and some of his contemporaries, such as de facto leader of Greece Eliftherios Venizelos and de facto co-dictator of Germany General Erich Ludendorff.[40]

Personal life[]

He married (later known as Hayriye Talaat Bafralı), an Albanian girl from Yanya (Ioannina) on 19 March 1910.[115] Talaat learned to speak French in the Israelite School, and picked up Greek from his wife. They learned in 1911 that they weren't able to father children.[116]

Legacy[]

Talaat Pasha is widely considered one of the main architects of the Armenian Genocide by historians.[117]

Shortly after the assassination of Talaat in March 1921, the "Posthumous Memoirs of Talaat" were published in the October volume of The New York Times Current History.[118] In his memoir, Talaat admitted to purposefully deporting the Armenians to the Ottoman Empire's eastern provinces in a prepared scheme. He however blamed Armenian civilians themselves for the deportations, implying the civilian population could have caused a revolution.[119][120]

Hans-Lukas Kieser states that many Jews engaged in "open propaganda for him and CUP causes" despite Talaat's involvement in genocide, and that this continued even after Talaat's death into the late twentieth century.[121]

Within modern Turkey, criticism only focuses on Talaat and the rest of the Three Pashas for causing the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I and its subsequent partitioning by the Allies. Turkey's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk widely criticized Talaat Pasha and his colleagues for their policies during and immediately prior to the First World War.[122] Talaat Pasha is viewed as a "great statesman, skillful revolutionary, and farsighted founding father" in Turkey, where many schools, streets, and mosques are named after him.[9]

Hans Lukas Kieser writes in his brography of Talaat in Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide

The Ottoman signature political animal [Talaat Pasha] held up a distorting mirror to Europe. It showed the worst yet nevertheless real sides of Europe, scaled up. Unconcerned by rules and ethics, arguing that he saw both broken numerous times by the European powers, he began to use the ruthless arms of a comparatively weak actor also wanting empire: extortion and aggression toward weaker ones who could not fight back.

In film[]

Talaat is depicted in two films:

- The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (by Michael Constantine)

- The Promise

See also[]

- The Remaining Documents of Talaat Pasha

- The Memoirs of Naim Bey

Notes[]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Balint Jennifer (2013). "The Ottoman State Special Military Tribunal for the Genocide of the Armenians: 'Doing Government Business'". In Kevin Heller; Gerry Simpson (eds.). The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199671144.003.0004. ISBN 9780199671144.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. xiii.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act. New York City: Holt & Co. pp. 165, 186–187.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: Genocide and Extermination in World History from Carthage to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 414.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Alan S. (2001). Is the Holocaust Unique?. Westview Press. pp. 122–123.

- ^ Naimark, Norman (2001). Fires of hatred. Harvard University Press. p. 57.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. xi.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kedourie, Sylvia; Wasti, S. Tanvir (1996). Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. p. 96. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. xii.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 41.

- ^ They believed that he lacked race and breeding; they scornfully reported that he was of gypsy origin. For more see: David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, Henry Holt and Company, 2010, ISBN 1429988525, p. 39.

- ^ He was born in the province of Edirne (the westernmost part of Turkey) in 1874, the child of a farmer and a gypsy woman. For more see: Michael Newton, Age of Assassins: A History of Conspiracy and Political Violence, 1865-1981, Faber & Faber, 2012, ISBN 0571290469, p. 49.

- ^ Among the top party functionaries were Interior Minister Talaat Pasha (Bulgarian Gypsy); For more see: Stephen R. Graubard, The Armenian Genocide in Perspective, Routledge, 2017, ISBN 1351485830, p. 93.

- ^ Young Turk leaders, Talat was not ethnically Turkish; rather he was of Pomak descent. For more see: Eric Bogosian, Operation Nemesis: The Assassination Plot that Avenged the Armenian Genocide, Hachette UK, 2015, ISBN 031629201X,p. 75.

- ^ Oddly enough, had Zia Bey lived to see the success of the Young Turk movement, after the revolution of 1908, he might have salaamed to Talaat, the Grand Vizier of the Young Turks, a Pomak gipsy. Such are the ironies of politics. For more see: George Young, Constantinople, Barnes & Noble, 1992, ISBN 1566190843, p. 210.

- ^ Galip, Özlem Belçim (2020). "Revisiting Armenians in the Ottoman Empire: Deportations and Atrocities". New Social Movements and the Armenian Question in Turkey: Civil Society vs. the State. Springer International Publishing. pp. 21–36. ISBN 978-3-030-59400-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). p.41

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mango, Andrew (2004). Atatürk. London: John Murray. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7195-6592-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mango 2002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018), pp,42–43

- ^ Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018), p.43

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 46-49.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 53.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 68.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 72.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 74.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 85-86.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 82-83.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 117.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 130.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 211.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 125.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 219.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 143.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 146.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 176.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 177.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 160.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 200.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 208.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 170-171.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 215.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 191-192.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 222.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 224.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 225-226.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 228, 229.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steven L. Jacobs (2009). Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lexington Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7391-3589-1.

On 24 April 1915 the Ministry of the Interior ordered the arrest of Armenian parliamentary deputies, former ministers, and some intellectuals. Thousands were arrested, including 2,345 in the capital, most of whom were subsequently executed ...

- ^ Demourian, Avet (25 April 2009). "Armenians mark massacre anniversary". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). "Tehcir Law". In Whitehorn, Alan (ed.). The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610696883.

- ^ Josh Belzman (23 April 2006). "PBS effort to bridge controversy creates more". Today.com. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ^ "Exiled Armenians starve in the desert; Turks drive them like slaves, American committee hears ;- Treatment raises death rate". New York Times. 8 August 1916. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199350711.

- ^ Hewitt, William L. (2004). Defining the horrific readings on genocide and Holocaust in the twentieth century. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 100. ISBN 013110084X.

- ^ Bardakçı, Murat (2008). Talât Paşa'nın evrak-ı metrûkesi (in Turkish) (4. ed.). Cağaloğlu, İstanbul: Everest Yayınları. p. 211. ISBN 978-9752895607.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 292.

- ^ Ihrig, Stefan (2016). Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler. Harvard University Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-674-50479-0.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 269.

- ^ Morgenthau, Sr., Henry (1919). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page. p. 339.

'I wish,' Talaat now said, 'that you would get the American life insurance companies to send us a complete list of their Armenian policy holders. They are practically all dead now and have left no heirs to collect the money. It of course all escheats to the State. The Government is the beneficiary now. Will you do so?'

This was almost too much, and I lost my temper.

'You will get no such list from me,' I said, and I got up and left him. - ^ A., Bernstorff (2011). Memoirs of Count Bernstorff. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-169-93525-9.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 239.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 257-258.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 259.

- ^ Üngör, Umut. "Young Turk social engineering : mass violence and the nation state in eastern Turkey, 1913- 1950" (PDF). University of Amsterdam. pp. 217–226. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 260.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 260-261.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser, Hans-Lukas; Anderson, Margaret Lavinia; Bayraktar, Seyhan; Schmutz, Thomas, eds. (2019). The End of the Ottomans: The Genocide of 1915 and the Politics of Turkish Nationalism. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-78831-241-7.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 322-323.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 323.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 362-363.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 369.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 372.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 379.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 381.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kedourie, Sylvia (1996). Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 381-385.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 385.

- ^ Olson 1986.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 388.

- ^ V. Dadrian, The History of the Armenian Genocide, pp. 323-324.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 382.

- ^ Herbert, Aubrey (1925). Ben Kendim: A Record of Eastern Travel. G. P. Putnam's sons ltd. p. 41. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- ^ Kedourie, Sylvia (1996). Turkey: Identity, Democracy, Politics. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 0-7146-4718-7.

- ^ Operationnemesis.com

- ^ "Robert Fisk: My conversation with the son of Soghomon Tehlirian". The Independent. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hosfeld 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hosfeld 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kieser 2018, p. 405.

- ^ Ihrig 2016, p. 232.

- ^ Olson 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Olson 1986, p. 46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hofmann 2020, p. 76.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 420.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 419.

- ^ Olson 1986, p. 52.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 329.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 62.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 214.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 380–382. ISBN 978-0-691-15956-0.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 64.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 63.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 96.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 286.

- ^ Hosfeld 2005, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Ergun Hiçyılmaz (1993). Başverenler, başkaldıranlar. Altın Kitaplar Kitabevi. p. 92. ISBN 9789754053807 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 90.

- ^ Alayaria, Aida; Consequences of Denial: The Armenian Genocide, Page 182, 2008, Karnac Books Ltd

- ^ Talaat Pasha, "Posthumous Memoirs of Talaat Pasha", The New York Times Current History, Vol. 15, no. 1 (October 1921): 295

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard (1987). The Armenian Genocide in Perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 142.

I admit that we deported Armenians from our eastern provinces, and we acted in this matter upon a previously prepared scheme. The responsibility of these acts falls upon the deported people themselves. Russians ... had armed and equipped the Armenian inhabitants of this district [Van] ... and had organized strong Armenian bandit forces. ... When we entered the Great War, these bandits began their destructive activities in the rear of the Turkish army on the Caucasus front, blowing up the bridges and killing the innocent Mohammedan inhabitants regardless of age and sex... All these Armenian bandits were helped by the native Armenians.

- ^ Henry Morgenthau. Ambassador Morgenthau's Story (PDF). Blackmask Online. p. 112. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

Naturally the Christians became alarmed when placards were posted in the villages and cities ordering everybody to bring their arms to headquarters. Although this order applied to all citizens, the Armenians well understood what the result would be, should they be left defenseless while their Moslem neighbours were permitted to retain their arms. In many cases, however, the persecuted people patiently obeyed the command; and then the Turkish officials almost joyfully seized their rifles as evidence that a "revolution" was being planned and threw their victims into prison on a charge of treason. Thousands failed to deliver arms simply because they had none to deliver, while an even greater number tenaciously refused to give them up, not because they were plotting an uprising, but because they proposed to defend their own lives and their women's honour against the outrages which they knew were being planned. The punishment inflicted upon these recalcitrants forms one of the most hideous chapters of modern history. Most of us believe that torture has long ceased to be an administrative and judicial measure, yet I do not believe that the darkest ages ever presented scenes more horrible than those which now took place all over Turkey.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 313.

- ^ Muammer Kaylan (8 April 2005). The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books, Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

Sources[]

- Hofmann, Tessa (2020). "A Hundred Years Ago: The Assassination of Mehmet Talaat (15 March 1921) and the Berlin Criminal Proceedings against Soghomon Tehlirian (2/3 June 1921): Background, Context, Effect" (PDF). International Journal of Armenian Genocide Studies. 5 (1): 67–90. doi:10.51442/ijags.0009. ISSN 1829-4405.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7. (Google Books)

- Olson, Robert W. (1986). "The Remains of Talat: A Dialectic between Republic and Empire". Die Welt des Islams. 26 (1/4): 46–56. doi:10.2307/1570757. ISSN 0043-2539. JSTOR 1570757.

- Mango, Andrew (2002). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-1585673346.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Talaat Pasha. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Talaat Pasha |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mehmed Talat |

- First World War.com: Talat Pasha's Alleged Orders Regarding the Armenian Massacres

- Interview with Talaat Pasha by Henry Morgenthau – American Ambassador to Constantinople 1915

- Talaat Pasha's report on the Armenian Genocide

- Mehmet Talaat (1874–1921) and his role in the Greek Genocide

- Newspaper clippings about Talaat Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/talat-pasa

- 1874 births

- 1921 deaths

- People from Kardzhali

- People convicted by the Ottoman Special Military Tribunal

- Greek genocide

- Pashas

- People sentenced to death in absentia

- Assassinated people of the Ottoman Empire

- Deaths by firearm in Germany

- 20th-century Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire

- Recipients of Ottoman royal pardons

- Committee of Union and Progress politicians

- Pan-Turkists

- Ottoman people of World War I

- Young Turks

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiators

- People of the Ottoman Empire of Pomak descent

- People assassinated by Operation Nemesis

- Armenian genocide perpetrators

- Sayfo perpetrators

- Government ministers of the Ottoman Empire

- Political office-holders in the Ottoman Empire

- Totalitarian rulers

- People from Edirne

- Politicians of the Ottoman Empire

- Turkish nationalists

- Turkish revolutionaries