Templestowe, Victoria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

| Templestowe Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

Templestowe | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°45′11″S 145°08′06″E / 37.753°S 145.135°ECoordinates: 37°45′11″S 145°08′06″E / 37.753°S 145.135°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 16,618 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,130/km2 (2,928/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3106 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 14.7 km2 (5.7 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 16 km (10 mi) from Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Manningham | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Menzies | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

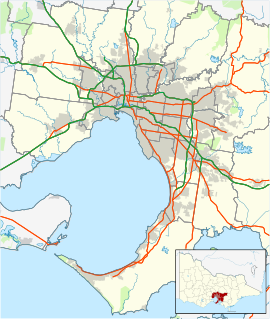

Templestowe is a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 16 km north-east of Melbourne's Central Business District.[2] Its local government area is the City of Manningham. At the 2016 census, Templestowe had a population of 16,618.[1]

The suburb has a number of natural attractions, including parklands, contrasted with large shopping malls.

Geography[]

Templestowe is located in the north-eastern area of Melbourne. Templestowe is bordered by the Yarra River, King Street, Victoria Street, Blackburn Road and some parks.

Gentle, rolling hills extend from east of the Yarra River flood plains, along Templestowe Road (towards the Eastern Freeway) for seven km (4.3 miles), to the north-east. The altitude of the plain above sea level is 50 m, and the topography is subdued and mostly flat; the hills are just below 60 m, the slopes rounded and there are several forested gullies.

Degradation of the soils in the steep slopes at the river's edge has been exacerbated over the last century by unsustainable agricultural processes (such as the harvesting of storm-felled trees), deforestation and the introduction of rabbits. Following the 2006 drought, the community newspaper had reported several times that the population was only brought under control in 2007, 12 years after baiting programs were begun[3][failed verification] and that more conservation funding is needed to halt the loss of vegetation along the river.[4] Most of the surrounding area has been cleared for agricultural and orchard use, although an "urban forest" exists in the densely populated rural-residential areas.[5] There is a wide diversity of growth within the flood plain.

Climate[]

Most of the area corresponds to the climate recorded in Melbourne, though some variation has been recorded in the hills to the north-east.[citation needed]

Geology[]

A report from The Argus in 1923 gives rare insight to interest in the area. It had been recently accepted that "when the coastal plain is overweighted the back country rises" due to inexorable forces moulding the surface of the Earth and the so-called "Templestowe anticline" was studied as representative of microscopic faulting, which accommodated this elevation of the eastern suburbs. It was observed that the new reserve grounds established along it would become a "Mecca" for geologists:[6]

at the better geological sections... [there are] folded rocks, which were originally soft mudstones, but now hardened by the forces induced through [lateral] pressure, often sheared and thrust out of position. The saddleback thus produced naturally opened out at the summit of the old, and the cracks that were formed w[h]ere [w]ater filled in with milky quartz veins... [are now, after being mined] full of cavities which were once occupied...

History[]

The land to the east of Melbourne was inhabited by the Wurundjeri people, who had lived in the Yarra River Valley and its tributaries for 40,000 years.[7] Europeans first began to settle in the mid-1830s, and George Langhorne, a missionary in Port Phillip from 1836 to 1839, noted that a substantial monetary trade with the new settlers was "well established" by 1838: "A considerable number of the Aboriginal people obtain food and clothing for themselves by shooting the Menura pheasant or Bullun-Bullun for the sake of the tails, which they sell to the whites."[8] The increasingly rapid acquisition of guns, the lure of exotic foods and a societal emphasis on maintaining kin relationships meant they weren't attracted to the mission.[9]

In the 1850s, the Aboriginals were granted "permissive occupancy" of Coranderrk Station, near Healesville and forcibly[nb 1] resettled. According to John Green, the Inspector of Aboriginal Stations in Victoria and later manager of Corranderrk,[10] the people were able to achieve a "sustainable" degree of economic independence: "In the course of one week or so they will all be living in huts instead of willams [traditional housing]; they have also during that time [four months] made as many rugs, which has enabled them to buy boots, hats, coats etc., and some of them [have] even bought horses."[11]

Around 1855 another bridge was built nearby in what is now Lower Plenty, built over the Plenty River. This bridge, made up of bluestone blocks and steel, still stands today and is part of the Plenty River Trail, close to the Heidelberg Golf Club and the Lower Plenty Hotel. It is possible that the Templestowe Bridge was similar in appearance to this.

Founding families[]

There was an early settlement of Irish and Scottish folk from the ship "Midlothian", through Bulleen and Templestowe, which had arrived in June 1839. The grassland there was interspersed with large Manna and River Red (Be-al) gum trees and broken up by chains of lagoons, the largest of which, called Lake Bulleen, was surrounded by impenetrable reeds that stove off attempts to drain it for irrigation.[12] Due to the distribution of raised ground, the flats were always flooding and for a long time only the poorest (non-English) immigrants leased "pastoral" land from Unwins Special Survey, the estate of the Port Phillip District Authority. Hence, although far from prosperous, the farmers living close to nature, most were independent, such that a private Presbyterian school[nb 3] was begun for the district in 1843.

Pontville Homestead[]

Pontville is historically and aesthetically significant amongst the early towns, as its landscape contributes to the greater understanding of 1840s agricultural and garden history, as well as for containing numerous relics of aboriginal life. The survival of its formal garden terracing and the presence Hawthorn hedgerows, used for fencing, is unusual. In his book[13] on pastoralism in Tasmania and the 1920s conflict with the island natives, Keith Windschuttle writes:

In the 1820s [and 1830s], some settlers began to plant the hawthorn hedges that remain part of the Tasmanian landscape today. However, this was also a slow and expensive process. The plants had to survive several months of sea transport from England and one mile of hedgerow required between 8,000 and 10,500 plants. The early hedges were used primarily as windbreaks for the house, and were planted close to it. Before the 1830s, Sharon Morgan writes, 'stone walls were almost unknown, and hedges were rare'.

The property itself (now subdivided) has several remnant plantings of the colonial era, including Himalayan Cypress, Black Mulberry and willow trees and the integrity of ancient scar trees, ancestral camping sites and other spirit places of the Wurundjeri aborigines, which was respected by the Newman family. They can be observed in their original form along the trail systems, at the Tikalara ("meeting place") plains tract of the Mullum-Mullum Creek.[14]

Pontville is archaeologically important for the below ground remains inherent in the location of, and the material contained within the archaeological deposits associated with Newman's turf hut and the subsequent homestead building, cottage, associated farm and rubbish deposits. The structures, deposits and associated artefacts are important for their potential to provide an understanding of the conditions in which a squatting family lived in the earliest days of the Port Phillip settlement.[15]

Namesake[]

The name Templestowe was chosen when a village was proclaimed. Its exact origins are unknown, although a "Templestowe" is mentioned in the book Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott – supposedly modelled after the Temple Newsam preceptory at Leeds.[16] As the village of Ivanhoe was settled immediately prior to Templestowe, it is believed by some that the name was chosen to preserve the literary parallel.

Templestowe Post Office opened on 1 July 1860.[17]

Development[]

The "River Peel" sculpture was installed in 2001, as part of the Manningham City Gateway Sculpture Project.[18]

Until the expansionism of the 1970s, Templestowe was scarcely populated. Additionally, it was then part of the so-called "green belt" of Melbourne and subdivision into less than 20,000 m² (2 hectares) was not possible in many parts of the suburb.[citation needed]

Transport[]

Templestowe lies between two of Melbourne's suburban rail lines, (the Hurstbridge and Belgrave/Lilydale lines), which hindered the area's development. In the 1970s, the Doncaster line was planned by the State Government to run down the middle of the Eastern Freeway, and then veer away from the freeway to run towards the suburb. However, the land acquired for the off-freeway section was sold in the 1980s.[19]

Suburban development began in earnest in the 1970s and, while there is still no rail service, there is now a bus network operating routes to Melbourne in the west, Box Hill and Blackburn in the south, and Ringwood in the east. The service frequency is comparatively poor, with average times of an hour between buses in the off-peak, and few services running after 10pm, although there was some improvement in the late 2000s under the Victorian Government's $1.4 billion "SmartBus" program.[20]

Following the 2008 Eddington Report into improving east-west travel in the Melbourne area, which included 20 recommendations for the eastern suburban area, the professor of public transport,[21] at Monash University, Graham Currie, gave his support to expanding the bus transit system (eight older vehicles were replaced in 2007)[22] and argued the need for rapid-transit bus lanes throughout the City of Manningham as an alternative to developing light and heavy rail. That involves "separate road space so [specialised buses] don't have to wait in traffic or at traffic lights" as a solution to road congestion, without need for the extension of tram route 48 to Doncaster Hill, favoured by the Manningham City Council.[23]

Education[]

There are currently five state schools (Serpell, Templestowe Heights, Templestowe Park and Templestowe Valley) and two Catholic schools (Saint Charles Borromeo and Saint Kevin's), providing primary education to the suburb. Templestowe College serves some of the demand for secondary education. However, Templestowe College, Templestowe Valley Primary School, St Kevins PS and Templestowe Heights PS are located either on the border of Templestowe and Templestowe Lower or in Templestowe Lower.

Sport[]

The suburb has an Australian Rules football team, the Templestowe Dockers, competing in the Eastern Football League.[24] Their junior team competes in the Yarra Junior Football League.

The Bulleen Templestowe Amateur Football Club competes in the Victorian Amateur Football Association (VAFA).[25] The "Bullants" are a proud family club, who have had some recent premiership success at senior level (2004, 2008, 2012). The Reserves side were also Premiers in 2012, making it a very successful year for the Club after building upon the success of their Under 19's who were Premiers in 2011.[26] The Club were promoted to Division 1 of the Victorian Amateur Football Association for the 2013 season.

The suburb also had a cricket team, the Templestowe Cricket Club, competing in the Box Hill Reporter District Cricket Association. The two football clubs and the cricket club share use of the Templestowe Reserve.

Manningham United FC also has a rich history. The Templestowe located club has been around since 1965, including winning the Dockerty Cup in 1984 when they were known as Fawkner. Manningham is currently the only soccer club located in Templestowe. Although there is a club called , it is actually located in Bulleen.

See also[]

- City of Doncaster and Templestowe – the former local government area of which Templestowe was a part

Footnotes[]

- ^ Green records that by the 1850s the situation had "got pretty bad for the local Aboriginals, and the [conflict over land] was brought to a head when the local First Nations people were visited by a few relatives from Drouin way. They then started to go on their traditional walkabout route, and much to the consternation of local settlers, began a corroborree at a traditional site in Bulleen, and then moved to Pound Bend [near Warrandyte] where it lasted two weeks. Troopers were ultimately called out when the tribe failed to return to their camp at Pound Bend. A number were arrested and sent to the police stockade at Dandenong. The remainder [there were no more than eighteen remaining in the district at last count, in 1862] were ultimately sent to the new Aboriginal reserve in Healesville, and Templestowe's 'Aboriginal problem' was quickly solved."

- ^ Seven graves of the Newman family were dug up. Poulter notes that Major Charles Newman died in 1863 aged 83 years, as recorded in his death certificate, whereas according to the tombstone he died in 1866 aged 80 years. This suggests that little attention to process was made.

- ^ Which did not qualify for Government aid.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Templestowe". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ http://www.postcodes-australia.com/postcodes/3106

- ^ "Rabbit control pays off". Manningham Leader. 20 August 2008.

- ^ Allen, Stacy (31 December 2007). "Growth harms waterways". Manningham Leader. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "City of Manningham Biodiversity Initiatives Program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2008. (709 KiB). Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Chapman, F. (22 September 1923). "Beauty Spot for Balwyn". The Argus. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ McBriar, Marilyn; Loder and Bayly (October 1985). "Historic Riverland Landscape Assessment" (PDF). Heidelberg Conservation Study Part 2. p. 63.

- ^ Langhorne, George (c. 1839). Aborigines of Port Phillip. Inward Registry, Port Phillip District Authority. p. 229.

- ^ Cahir, Fred (2005). "Dallong (Possum Skin Rugs): A Study of an Inter-Cultural Trade Item in Victoria" (PDF). Provenance. Public Record Office Victoria (4): 2–3. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "The Aborigines of Victoria: The Yarra and Western Port" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2008. (1388.4 KiB). Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Yallock, Woori; S. Wiencke (1984). When the wattles bloom again: the life and times of William Barak, last chief of the Yarra Yarra tribe. p. 52.

- ^ Green, Irvine (1987). Petticoats in the Orchard. Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society. pp. 3–7. ISBN 0-9500920-9-6.

- ^ Windschuttle, Keith (2002). The Fabrication of Aboriginal History Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847. Macleay Press. p. 80. ISBN 1-876492-05-8.

- ^ Mullum Mullum Creek Linear Park: Vision, Major Reserves, Bushlinks and Greenlinks Archived 6 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 January 2008

- ^ Heritage Council of Victoria

- ^ Wood, Edward F. L. (26 September 1922). "Hampton Court of the North: Historic Mansion For Leeds., Preserving Great Traditions". The Times (43146). p. 11.

- ^ Phoenix Auctions History. "Post Office List". Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Anonymous (March 2001). "Melbourne: Public art. (Radar: Projects)". Architecture Australia. 90 (2): 36.

- ^ Stephen Cauchi (February 1998). "Whatever Happened to the Proposed Railway to Doncaster East". Newsrail. Australian Railway Historical Society (Victorian Division). 26 (2): 40–44.

- ^ "ALP response November 7, 2006 to MTF transport survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2007. (22.1 KiB). Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "Chair of Public Transport, Department of Civil Engineering". Monash University. 2 May 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ "Council Information: More buses". Manningham Matters. Manningham City Council. August 2008.

- ^ Heagney, Melissa (15 July 2008). "Roads to nowhere?". Melbourne Weekly Eastern. Fairfax Community Network.

- ^ Full Point Footy. "Eastern Football League". Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ http://www.vafa.com.au/

- ^ http://www.btafc.com.au/

- Ellender, Isabel (1990). "The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the Archaeological Survey of Aboriginal Sites" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2008. (6853 KiB) Retrieved on 23 August 2008.

- Green, Irvine (1989). Aborigines of Bulleen: The history of the Wurundjeri Tribe who inhabited the area which became the City of Doncaster and Templestowe. Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society. pp. 25–40. ISBN 0-947353-00-3.

- Poulter, Hazel (1985). Templestowe: A Folk History. Templestowe: J. Poulter. pp. 1–55. ISBN 0-949196-00-2.

- William Thomas' map of the Western Port Phillip District. Note that the two pioneer settlements west of the city are described (illegibly) as a group of "various splitters, lum[ber]".

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Templestowe, Victoria. |

- Suburbs of Melbourne