Textual criticism of the New Testament

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (April 2011) |

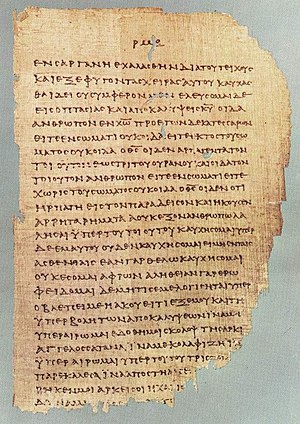

Textual criticism of the New Testament is the identification of textual variants, or different versions of the New Testament, whose goals include identification of transcription errors, analysis of versions, and attempts to reconstruct the original text. Its main focus is studying the textual variants in the New Testament.

The New Testament has been preserved in more than 5,800 Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Ethiopic and Armenian. There are approximately 300,000 textual variants among the manuscripts, most of them being the changes of word order and other comparative trivialities.[1][2]

Purpose[]

After stating that their 1881 critical edition was 'an attempt to present exactly the original words of the New Testament, so far as they can now be determined from surviving documents', Hort (1882) wrote the following on the purpose of textual criticism:

Again, textual criticism is always negative, because its final aim is virtually nothing more than the detection and rejection of error. Its progress consists not in the growing perfection of an ideal in the future, but in approximation towards complete ascertainment of definite facts of the past, that is, towards recovering an exact copy of what was actually written on parchment or papyrus by the author of the book or his amanuensis. Had all intervening transcriptions been perfectly accurate, there could be no error and no variation in existing documents. Where there is variation, there must be error in at least all variants but one; and the primary work of textual criticism is merely to discriminate the erroneous variants from the true.[3]

Text-types[]

The sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, chiefly in that it makes stemmatics in many cases impossible, because many copyists used two or more different manuscripts as sources. Consequently, New Testament textual critics have adopted eclecticism after sorting the witnesses into three major groups, called text-types (also styled unhyphenated: text types). The most common division today is as follows:[citation needed]

| Text-type | Date | Characteristics | Bible version |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Alexandrian text-type (also called the "Neutral Text" tradition; less frequently, the "Minority Text") |

2nd–4th centuries CE | This family constitutes a group of early and well-regarded texts, including Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus. Most representatives of this tradition appear to come from around Alexandria, Egypt and from the Alexandrian Church. It contains readings that are often terse, shorter, somewhat rough, less harmonised, and generally more difficult. The family was once[when?] thought[by whom?] to result from a very carefully edited 3rd-century recension, but now is believed to be merely the result of a carefully controlled and supervised process of copying and transmission. It underlies most translations of the New Testament produced since 1900. | NIV, NAB, NABRE, Douay, JB and NJB (albeit, with some reliance on the Byzantine text-type), TNIV, NASB, RSV, ESV, EBR, NWT, LB, ASV, NC, GNB, CSB |

| The Western text-type | 3rd–9th centuries CE | Also a very early tradition, which comes from a wide geographical area stretching from North Africa to Italy and from Gaul to Syria. It occurs in Greek manuscripts and in the Latin translations used by the Western church. It is much less controlled than the Alexandrian family and its witnesses are seen to be more prone to paraphrase and other corruptions. It is sometimes called the Caesarean text-type. Some New Testament scholars would argue that the Caesarean constitutes a distinct text-type of its own. | Vetus Latina |

| The Byzantine text-type; also, Koinē text-type (also called "Majority Text") |

5th–16th centuries CE | This group comprises around 95% of all the manuscripts, the majority of which are comparatively very late in the tradition. It had become dominant at Constantinople from the 5th century on and was used throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. It contains the most harmonistic readings, paraphrasing and significant additions, most of which are believed[by whom?] to be secondary readings. It underlies the Textus Receptus used for most Reformation-era translations of the New Testament. | Bible translations relying on the Textus Receptus which is close to the Byzantine text: KJV, NKJV, Tyndale, Coverdale, Geneva, Bishops' Bible, OSB |

History of research[]

Classification of text-types (1734–1831)[]

18th-century German scholars were the first to discover the existence of textual families, and to suggest some were more reliable than others, although they did not yet question the authority of the Textus Receptus.[4] In 1734, Johann Albrecht Bengel was the first scholar to propose classifying manuscripts into text-types (such as 'African' or 'Asiatic'), and to attempt to systematically analyse which ones were superior and inferior.[4] Johann Jakob Wettstein applied textual criticism to the Greek New Testament edition he published in 1751–2, and introduced a system of symbols for manuscripts.[4] From 1774 to 1807, Johann Jakob Griesbach adapted Bengel's text groups and established three text-types (later known as 'Western', 'Alexandrian', and 'Byzantine'), and defined the basic principles of textual criticism.[4] In 1777, Griesbach produced a list of nine manuscripts which represent the Alexandrian text: C, L, K, 1, 13, 33, 69, 106, and 118.[5] Codex Vaticanus was not on this list. In 1796, in the second edition of his Greek New Testament, Griesbach added Codex Vaticanus as witness to the Alexandrian text in Mark, Luke, and John. He still thought that the first half of Matthew represents the Western text-type.[6] In 1808, Johann Leonhard Hug (1765–1846) suggested that the Alexandrian recension was to be dated about the middle of the 3rd century, and it was the purification of a wild text, which was similar to the text of Codex Bezae. In result of this recension interpolations were removed and some grammar refinements were made. The result was the text of the codices B, C, L, and the text of Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria.[7][8]

Development of critical texts (1831–1881)[]

Karl Lachmann became the first scholar to publish a critical edition of the Greek New Testament (1831) that was not simply based on the Textus Receptus anymore, but sought to reconstruct the original biblical text following scientific principles.[4] Starting with Lachmann, manuscripts of the Alexandrian text-type have been the most influential in modern critical editions.[4] In the decades thereafter, important contributions were made by Constantin von Tischendorf, who discovered numerous manuscripts including the Codex Sinaiticus (1844), published several critial editions that he updated several times, culminating in the 8th: Editio Octava Critica Maior (11 volumes, 1864–1894).[4] The 1872 edition provided a critical apparatus listing all the known textual variants in uncials, minuscules, versions, and commentaries of the Church Fathers.[4]

The critical method achieved widespread acceptance up until in the Westcott and Hort text (1881), a landmark publication that sparked a new era of New Testament textual criticism and translations.[4] Hort rejected the primacy of the Byzantine text-type (which he called "Syrian") with three arguments:

- The Byzantine text-type contains readings combining elements found in earlier text-types.

- The variants unique to the Byzantine manuscripts are not found in Christian writings before the 4th century.

- When Byzantine and non-Byzantine readings are compared, the Byzantine can be demonstrated not to represent the original text.[4]

Having diligently studied the early text-types and variants, Westcott and Hort concluded that the Egyptian texts (including Sinaiticus (א) and Vaticanus (B), which they called "Neutral") were the most reliable, since they seemed to preserve the original text with the least changes.[4] Therefore, the Greek text of their critical edition was based on this "Neutral" text-type, unless internal evidence clearly rejected the reliability of particular verses of it.[4]

Until the publication of the Introduction and Appendix of Westcott and Hort in 1882, scholarly opinion remained that the Alexandrian text was represented by the codices Vaticanus (B), Ephraemi Rescriptus (C), and Regius/Angelus (L).[citation needed] The Alexandrian text is one of the three ante-Nicene texts of the New Testament (Neutral and Western).[citation needed] The text of the Codex Vaticanus stays in closest affinity to the Neutral Text.[citation needed]

Modern scholarship (after 1881)[]

The Novum Testamentum Graece, first published in 1898 by Eberhard Nestle, later continued by his son Erwin Nestle and since 1952 co-edited by Kurt Aland, became the internationally leading critical text standard amongst scholars, and for translations produced by the United Bible Societies (UBS, formed in 1946).[4] This series of critical editions, including extensive critical apparatuses, is therefore colloquially known as "Nestle-Aland", with particular editions abbreviated as "NA" with the number attached; for example, the 1993 update was the 27th edition, and is thus known as "NA27" (or "UBS4", namely, the 4th United Bible Societies edition based on the 27th Nestle-Aland edition).[4] Puskas & Robbins (2012) noted that, despite significant advancements since 1881, the text of the NA27 differs much more from the Textus Receptus than from Westcott and Hort, stating that 'the contribution of these Cambridge scholars appears to be enduring.'[4]

After discovering the manuscripts