The Broadway Melody

| The Broadway Melody (1929 film) | |

|---|---|

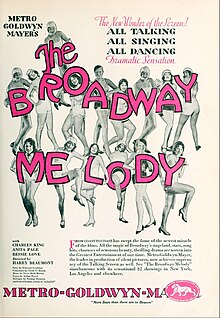

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Harry Beaumont |

| Written by | Sarah Y. Mason (continuity) Norman Houston (dialogue) James Gleason (dialogue) Uncredited: Earl Baldwin (titles) |

| Story by | Edmund Goulding |

| Produced by | Irving Thalberg Lawrence Weingarten |

| Starring | Charles King Anita Page Bessie Love Jed Prouty |

| Cinematography | John Arnold |

| Edited by | Sam S. Zimbalist Uncredited: William LeVanway (silent version) |

| Music by | (see article) |

| Color process | Black and White (with a Technicolor sequence) |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date | |

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $379,000[3] |

| Box office | $4.4 million[3] |

The Broadway Melody, also known as The Broadway Melody of 1929, is a 1929 American pre-Code musical film and the first sound film to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. It was one of the first musicals to feature a Technicolor sequence, which sparked the trend of color being used in a flurry of musicals that would hit the screens in 1929–1930.[4] Today, the Technicolor sequence survives only in black and white. The film was the first musical released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was Hollywood's first all-talking musical.

The Broadway Melody was written by Norman Houston and James Gleason from a story by Edmund Goulding, and directed by Harry Beaumont. Original music was written by Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown, including the popular hit "You Were Meant for Me". The George M. Cohan classic "Give My Regards to Broadway" is used under the opening establishing shots of New York City, its film debut. Bessie Love was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance.

Plot[]

Eddie Kearns (Charles King) sings "The Broadway Melody", and tells some chorus girls that he brought the Mahoney Sisters vaudeville act to New York to perform it with him in the latest revue being produced by Francis Zanfield (Eddie Kane). Harriet "Hank" Mahoney (Bessie Love) and her sister Queenie Mahoney (Anita Page) are awaiting Eddie's arrival at their apartment. Hank, the older sister, prides herself on her business sense and talent, while Queenie is lauded for her beauty. Hank is confident they will make it big while Queenie is less eager to put everything on the line to become a star. Hank declines the offer of their Uncle Jed (Jed Prouty) to join a 30-week traveling show but consents to think it over.

Eddie, who is engaged to Hank, arrives and sees Queenie for the first time since she was a girl and is instantly taken with her. He tells them to come to a rehearsal for Zanfield's revue to present their act. A blond woman sabotages their performance by placing a bag in the piano, which causes a fight with Hank. Zanfield isn't interested in it, but says he might have a use for Queenie, who begs him to give Hank a part as well, saying both will work for one wage. She also convinces him to pretend that Hank's business skills won him over. Eddie witnesses this exchange and becomes even more enamored of Queenie for her devotion to her sister. During a dress rehearsal for the revue, Zanfield says the pacing is too slow for "The Broadway Melody" and cuts Hank and Queenie from the number. Meanwhile, another woman is injured after falling off a set prop and Queenie is selected to replace her. Nearly everyone is captivated by Queenie, particularly notorious playboy Jacques "Jock" Warriner (Kenneth Thomson). While Jock begins to woo Queenie, Hank is upset that Queenie is building her success on her looks rather than her talent.

Over the following weeks, Queenie spends a lot of time with Jock, of which Hank and Eddie fervently disapprove. They forbid her to see him, which results in Queenie pushing them away and the deterioration of the relationship between the sisters. Queenie is only with Jock to fight her growing feelings for Eddie, but Hank thinks she's setting herself up to be hurt. Eventually, Eddie and Queenie confess their love for each other, but Queenie, unwilling to break her sister's heart, runs off to Jock once again.

Hank, after witnessing Queenie's fierce outburst toward Eddie and his devastated reaction to it, finally realizes that they are in love. She berates Eddie for letting Queenie run away and tells him to go after her. She claims to never have loved him and that she'd only been using him to advance her career. After he leaves, she breaks down and alternates between sobs and hysterical laughter. She composes herself enough to call Uncle Jed to accept the job with the 30-week show.

There's a raucous party at the apartment Jock had recently purchased for Queenie, but he insists that they spend time alone. When she resists his advances, he says that it's the least that she could do after all he's done for her. He begins to get physical, but Eddie bursts in and attempts to fight Jock, who knocks him through the door with one punch. Queenie runs to Eddie and leaves Jock and the party behind.

Some time later, Hank and Uncle Jed await the return of Queenie and Eddie from their honeymoon. The relationship between the sisters is on the mend, but there is obvious discomfort between Hank and Eddie. Queenie announces she's through with show business and will settle down in their new house on Long Island. She insists that Hank live with them when her job is over. After Hank leaves with her new partner and Uncle Jed, Queenie laments the fact that she wasn't able to help her sister find the happiness she deserves. Ironically, Hank's new partner is the blond who tried to sabotage the act when the sisters first arrived in New York. The final scene shows Hank on her way to the train station. She promises her new partner that they'll be back on Broadway within six months.[5]

Cast[]

- Anita Page as Queenie Mahoney

- Bessie Love as Harriet "Hank" Mahoney

- Charles King as Eddie Kearns

- Jed Prouty as Uncle Jed

- Kenneth Thomson as Jacques Warriner

- Edward Dillon as Stage Manager

- Mary Doran as Flo, the blonde

- Eddie Kane as Zanfield

- J. Emmett Beck as Babe Hatrick

- Marshall Ruth as Stew

- Drew Demarest as Turpe[2]

- James Gleason as Music Publisher (uncredited)

Musical numbers[]

Music by Nacio Herb Brown, lyrics by Arthur Freed, except as noted.[6][7]

- "Broadway Melody"

- "Love Boat"

- "You Were Meant for Me"

- "Wedding of the Painted Doll"

- "Boy Friend"

- "Truthful Deacon Brown" – music and lyrics by Willard Robison

- "Lovely Lady"

Production[]

As this was not just one of the first sound features made, but also one of the first sound musicals, the production used trial-and-error to learn how to record sound properly. After the rushes were seen, the sets would often be changed to improve the recording qualities, and scenes would be re-shot, resulting in long days for the actors and an overall long shooting schedule.[8] It took over three hours to film Bessie Love's brief ukulele-playing scene.[9] For earlier takes, a full orchestra was just off-camera, but, for later takes, the actors sang and danced to prerecorded music.[8]

A silent version of the film was also produced,[citation needed] as there were still many motion picture theaters without sound equipment at the time. The film featured a musical sequence for "The Wedding of the Painted Doll" that was presented in early two-color Technicolor (red and green filters). Color would quickly come to be associated with the musical genre, and numerous features were released in 1929 and 1930 that either featured color sequences or were filmed entirely in color, movies like On with the Show (1929), Gold Diggers of Broadway (1929), Sally (1929), The Life of the Party (1930), and others. No known color prints of the sequence survive, only black-and-white.

Reception and legacy[]

The Broadway Melody was a substantial success and made a profit of $1.6 million for MGM.[3] It was the top grossing picture of 1929, and won the Academy Award for Best Picture.[10]

Contemporary reviews from critics were generally positive. Variety wrote that it "has everything a silent picture should have outside of its dialog. A basic story with some sense to it, action, excellent direction, laughs, a tear, a couple of great performances and plenty of sex."[11] "Has everything", agreed Film Daily. "Sure-fire moneymaker that will drag 'em in everywhere."[12]

"This picture is great. It will revolutionize the talkies", wrote Edwin Schallert for Motion Picture News. "The direction is an amazing indication of what can be done in the new medium."[13]

Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times wrote a mixed review, calling it "rather cleverly directed" though "somewhat obvious", with sentiment "served out too generously in most of the sequences." Hall called King's performance "vigorous", but of Page he wrote, "Her acting, especially her voice, does not enhance her personality. Notwithstanding, it must be admitted that there are girls who talk as she is made to for the screen. Miss Page, however, fails to give one an impression of spontaneity, for she recites rather than speaks her lines."[14]

John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote, "The stage background allows opportunity for one or two musical interpolations, and no one is more glad than we that the talkies charmingly succeed in a very pleasant ballet. Because of that we shall try to forget the dialogue of the play, and that James Gleason ever wanted to take any credit for it."[15]

Historically, The Broadway Melody is often considered the first complete example of the Hollywood musical. While the film was seen as innovation for its time and helped to usher in the concept and structure of musical films, the film has become regarded by contemporary critics as cliché-ridden and overly melodramatic.[16] It currently holds a rating of 35% at Rotten Tomatoes based on 20 reviews, with a weighted average of 5.23/10. The site's consensus is that the film "is interesting as an example of an early Hollywood musical, but otherwise, it's essentially bereft of appeal for modern audiences".[17] Assessing the film in 2009, James Berardinelli wrote, "The Broadway Melody has not stood the test of time in ways that many of its more artistic contemporaries have. Some of its deficiencies can be attributed to ways in which the genre has been re-shaped and improved over the years, but some are the result of the studio's validated belief that viewers would be willing to ignore bad acting and pedestrian directing in order to experience singing, dancing, and talking on the silver screen."[18]

Sequels[]

Three more movies were later made by MGM with similar titles, Broadway Melody of 1936, Broadway Melody of 1938, and Broadway Melody of 1940. Although not direct sequels in the traditional sense, they all had the same basic premise of a group of people putting on a show (the films also had recurring cast members playing different roles, most notably dancer Eleanor Powell who appeared in all three).

The original movie was also remade in 1940 as Two Girls on Broadway. Another Broadway Melody film was planned for 1943 (starring Gene Kelly and Eleanor Powell), but production was cancelled when Kelly was loaned to Columbia for Cover Girl (1944).[1] Broadway Rhythm, a 1944 musical by MGM, was originally to have been titled Broadway Melody of 1944.

Awards and honors[]

This section does not cite any sources. (February 2019) |

At the 2nd Academy Awards, The Broadway Melody won for Best Picture. Harry Beaumont received a nomination for Best Director (lost to Frank Lloyd for The Divine Lady), and Bessie Love was nominated for Best Actress (lost to Mary Pickford for Coquette). No nominations were announced prior to the 1930 ceremonies. Love and Beaumont are presumed to have been under consideration, and are listed as such by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Home media[]

In 2005, The Broadway Melody was released on Region 1 special edition DVD by Warner Bros. It is also included in the 18-disc release Best Picture Oscar Collection, also released by Warner Bros.[19]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hess, Earl J.; Dabholkar, Pratibha A. (2009). Singin' in the Rain: The Making of an American Masterpiece. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-7006-1656-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Broadway Melody at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles, California: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ Richard W. Haines, list of first two-strip Technicolor (starting in 1928), in Technicolor Movies: The History of Dye Transfer Printing" (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2010), 15. ISBN 0786480750, 9780786480753

- ^ Green, Stanley (1999) Hollywood Musicals Year by Year (2nd ed.), pub. Hal Leonard Corporation ISBN 0-634-00765-3

- ^ Bloom, Ken. Hollywood Song: The Complete Film Musical Companion, Vol. 1, 1995. Published by Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-2668-8

- ^ "Music, The Broadway Melody (1929)" tcm.com, accessed March 4, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Love, Bessie (June 27, 1969). "A Broadway Melody Remembered". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 8.

- ^ Crafton, Donald (1990). "Three Seasons: The Films of 1928–1931". The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926–1931. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-684-19585-8.

- ^ Wierzbicki, James (2008). Film Music: A History. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-203-88447-8.

- ^ Silverman, Sid (February 13, 1929). "Broadway Melody". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. p. 13. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ "Broadway Melody". Film Daily. New York. February 17, 1929. p. 10.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (February 9, 1929). "First Report on 'Broadway Melody'". Motion Picture News. p. 433.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (February 9, 1929). "Review: "The Broadway Melody"". The New York Times.

- ^ Mosher, John (February 16, 1929). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 83.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (2003). All about Oscar: The History and Politics of the Academy Awards. Continuum. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8264-1452-6.

- ^ "The Broadway Melody". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (November 1, 2009). "The Broadway Melody". Reelviews. James Berardinelli. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Fischer, Lucy, ed. (2009). American Cinema of the 1920s: Themes and Variations. Rutgers University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8135-4485-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Broadway Melody. |

- The Broadway Melody at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Broadway Melody at IMDb

- The Broadway Melody at AllMovie

- The Broadway Melody at the TCM Movie Database

- The Broadway Melody at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Broadway Melody details at Virtual History

- 1929 films

- English-language films

- 1920s romantic musical films

- 1920s color films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- American romantic musical films

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Films about musical theatre

- Films directed by Harry Beaumont

- Films produced by Irving Thalberg

- Films set in New York City

- Films partially in color

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Early color films