The Business Man (short story)

| "The Business Man" | |

|---|---|

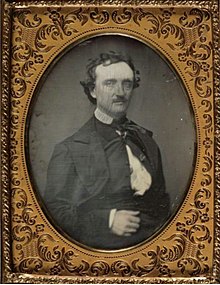

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Comedy |

| Publisher | Burton's Gentleman's Magazine |

| Media type | Print (periodical) |

| Publication date | February 1840 |

| Text | The Business Man at Wikisource |

"The Business Man" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe about a businessman boasting of his accomplishments. It was published in February 1840 in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine. The story questions the concept of a self-made man.

Plot summary[]

The narrator of the story is Peter Proffit, a "methodical" businessman by his own admission. He says a nurse swung him around when he was a young boy, and he bumped his head against a bedpost. That single event determined his fate: the resulting bump was in the area dedicated to system and regularity, according to phrenology.

Proffit goes on to say that he despises geniuses and that they are all asses—"the greater the genius the greater the ass." Geniuses can not, he says, be turned into men of business.

At the age of fourteen, his father forced him to work as a merchant, which Proffit could not stand. He says that though most boys run away from home at the age of twelve, he chose to wait until the age of sixteen. What finally convinced him was his mother's suggestion that he work as a grocer. Instead, he becomes a "Walking-Advertisement" for a tailor. Feeling swindled by his employer over a penny, however, he moves on to start his own business.

Proffit goes into the "Eye-Sore" business. When he sees a large home or palace being built, he buys a nearby or adjoining property and builds a "mud-hovel" or "pig-sty" so ugly that he is paid 500% the value of the lot to tear it down—essentially a species of spite house for extorting purposes. One owner, however, offers less than 500%. In retaliation, Proffit lamp-blacks the house overnight. For this, he is jailed, and ostracized by others in the Eye-Sore business.

Proffit then enters the Assault-and-Battery business. He makes money by starting fights with people on the streets and then sues them for attacking him. He then becomes involved with "Mud-Dabbling", making people pay him not to splash them with mud. He also has a dog rub up against people's shoes to make them dirty, then offers his services as a shoeshiner. Though he gave the dog a third of the profits, the routine split when the dog began to demand half.

Proffit then becomes an organ grinder, though he makes money by people paying him to stop rather than to play. He boasts of his own abilities in business and lists his eight "speculations" for success. He then tries forging letters and delivering them to rich people, asking them to pay postage themselves, as was the custom at the time. He says, however, that he had moral issues with this line of work after hearing people say unkind things about the fake people who had written to them.

A law is later passed to keep down the population of cats, with citizens paid for any cat tails they turn in. Proffit begins to raise cats so that he can collect the reward for their tails. It was his most profitable venture. After all his business ventures, he considers himself "a made man" and is considering running for office or, more accurately, purchasing a seat in county government.

Publication history[]

The story was originally titled "Peter Pendulum"[1] and published in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine in February 1840.[2] It was first published as "The Business Man" in the August 2, 1845, issue of the Broadway Journal.[3]

Analysis[]

The story is a satire[4] and is often interpreted as a reflection of Poe's strained relationship with his foster father John Allan, himself a successful businessman.[3] The story also satirizes businesspeople in general, suggesting that their success is not due to their method of punctuality and self-discipline but because of ruthless business practices, violence, egotism, and pure chance.[5] Poe also calls to question the concept of a "self-made man", expressing skepticism that such a concept is possible.[6] Like "The Man That Was Used Up", another of Poe's satires, this man is essentially hollow and worthless.[7]

In "The Business Man", Poe also makes fun of the dubious nature of phrenology, then a popular pseudoscience.[5]

In the story, the narrator asserts: "In biography, truth is every thing, and in autobiography it is especially so." This is ironic considering Poe's own tendency to alter his life story; he often omitted details of his military career, and invented stories about his nonexistent travels to Greece, Turkey, and Russia.[8]

Proffit's dog is named Pompey, a name Poe also uses for two African slave characters in "A Predicament" and in "The Man That Was Used Up".[9]

References[]

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 279. ISBN 081604161X.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998). Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (Paperback ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 294. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9.

- ^ a b Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 40. ISBN 081604161X.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.

- ^ a b Schnackertz, Hermann Josef. "Of Bumps and Brains: E. A. Poe and Phrenology", Lost Worlds & Mad Elephants: Literature, Science and Technology. Galda & Wilch, 1999. p. 67. ISBN 3-931397-16-5

- ^ Person, Leland S. "Poe and Nineteenth Century Gender Constructions" as collected in A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe, J. Gerald Kennedy, Ed. Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 158–159. ISBN 0-19-512150-3

- ^ Person, Leland S. "Poe and Nineteenth Century Gender Constructions" as collected in A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe, J. Gerald Kennedy, Ed. Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 159. ISBN 0-19-512150-3

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.

- ^ Goddu, Teresa A. "Poe, sensationalism, and slavery", The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Kevin J. Hayes (editor). New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. p. 101. ISBN 0-521-79727-6

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- List of editions of "The Business Man" at the Edgar Allan Poe Society online

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Raven Edition, Volume 4 public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Raven Edition, Volume 4 public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Short stories by Edgar Allan Poe

- 1840 short stories

- Works originally published in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine