The Murders in the Rue Morgue

| "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" | |

|---|---|

Facsimile of Poe's original manuscript for "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Detective fiction Short story |

| Published in | Graham's Magazine |

| Media type | Print (Magazine) |

| Publication date | April 1841 |

| Text | The Murders in the Rue Morgue at Wikisource |

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe published in Graham's Magazine in 1841. It has been described as the first modern detective story;[1][2] Poe referred to it as one of his "tales of ratiocination".[1]

C. Auguste Dupin is a man in Paris who solves the mystery of the brutal murder of two women. Numerous witnesses heard a suspect, though no one agrees on what language was spoken. At the murder scene, Dupin finds a hair that does not appear to be human.

As the first fictional detective, Poe's Dupin displays many traits which became literary conventions in subsequent fictional detectives, including Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. Many later characters, for example, follow Poe's model of the brilliant detective, his personal friend who serves as narrator, and the final revelation being presented before the reasoning that leads up to it. Dupin himself reappears in "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" and "The Purloined Letter".

Plot summary[]

The unnamed narrator of the story opens with a lengthy commentary on the nature and practice of analytical reasoning, then describes the circumstances under which he first met Dupin during an extended visit to Paris. The two share rooms in a dilapidated old mansion and allow no visitors, having cut off all contact with past acquaintances and venturing outside only at night. "We existed within ourselves alone," the narrator states. One evening, Dupin demonstrates his analytical prowess by deducing the narrator's thoughts about a particular stage actor, based on clues gathered from the narrator's previous words and actions.

During the remainder of that evening and the following morning, Dupin and the narrator read with great interest the newspaper accounts of a baffling double murder. Madame L'Espanaye and her daughter have been found dead at their home in the Rue Morgue, a fictional street in Paris. The mother was found in a yard behind the house, with multiple broken bones and her throat so deeply cut that her head fell off when the body was moved. The daughter was found strangled to death and stuffed upside down into a chimney. The murders occurred in a fourth-floor room that was locked from the inside; on the floor were found a bloody straight razor, several bloody tufts of gray hair, and two bags of gold coins. Several witnesses reported hearing two voices at the time of the murder, one male and French, but disagreed on the language spoken by the other. The speech was unclear, and all witnesses claimed not to know the language they believed the second voice to be speaking.

A bank clerk named Adolphe Le Bon, who had delivered the gold coins to the ladies the day before, is arrested even though there is no other evidence linking him to the crime. Remembering a service that Le Bon once performed for him, Dupin becomes intrigued and offers his assistance to "G–", the prefect of police.

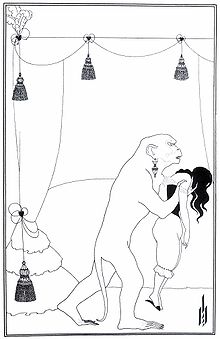

Because none of the witnesses can agree on the language spoken by the second voice, Dupin concludes they were not hearing a human voice at all. He and the narrator examine the house thoroughly; the following day, Dupin dismisses the idea of both Le Bon's guilt and a robbery motive, citing the fact that the gold was not taken from the room. He also points out that the murderer would have had to have superhuman strength to force the daughter's body up the chimney. He formulates a method by which the murderer could have entered the room and killed both women, involving an agile climb up a lightning rod and a leap to a set of open window shutters. Showing an unusual tuft of hair he recovered from the scene, and demonstrating the impossibility of the daughter being strangled by a human hand, Dupin concludes that an "Ourang-Outang" (orangutan) killed the women. He has placed an advertisement in the local newspaper asking if anyone has lost such an animal, and a sailor soon arrives looking for it.

The sailor offers to pay a reward, but Dupin is interested only in learning the circumstances behind the two murders. The sailor explains that he captured the orangutan while in Borneo and brought it back to Paris, but had trouble keeping it under control. When he saw the orangutan attempting to shave its face with his straight razor, imitating his morning grooming, it fled into the streets and reached the Rue Morgue, where it climbed up and into the house. The orangutan seized the mother by the hair and was waving the razor, imitating a barber; when she screamed in fear, it flew into a rage, ripped her hair out, slashed her throat, and strangled the daughter. The sailor climbed up the lightning rod in an attempt to catch the animal, and the two voices heard by witnesses belonged to it and to him. Fearing punishment by its master, the orangutan threw the mother's body out the window and stuffed the daughter into the chimney before fleeing.

The sailor sells the orangutan, Le Bon is released from custody, and G– mentions that people should mind their own business once Dupin tells him the story. Dupin comments to the narrator that G– is "somewhat too cunning to be profound", but admires his ability "de nier ce qui est, et d'expliquer ce qui n'est pas" (a quote from Julie, or the New Heloise by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: "to deny that which is, and explain that which is not").

Themes and analysis[]

In a letter to friend Dr. Joseph Snodgrass, Poe said of "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", "its theme was the exercise of ingenuity in detecting a murderer."[3] Dupin is not a professional detective; he decides to investigate the murders in the Rue Morgue for his personal amusement. He also has a desire for truth and to prove a falsely accused man innocent. His interests are not financial and he even declines a monetary reward from the owner of the orangutan.[4] The revelation of the actual murderer removes the crime, as neither the orangutan nor its owner can be held responsible.[5] Poe scholar speculates that later detective stories might have set up M. Le Bon, the suspect who is arrested, as appearing guilty as a red herring, though Poe chose not to.[6]

Poe wrote "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" at a time when crime was at the forefront in people's minds due to urban development. London had recently established its first professional police force and American cities were beginning to focus on scientific police work as newspapers reported murders and criminal trials.[1] "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" continues an urban theme that was used several times in Poe's fiction, in particular "The Man of the Crowd", likely inspired by Poe's time living in Philadelphia.[7]

The tale has an underlying metaphor for the battle of brains vs. brawn. Physical strength, depicted as the orangutan as well as its owner, stand for violence: the orangutan is a murderer, while its owner admits he has abused the animal with a whip. The analyst's brainpower overcomes their violence.[8] The story also contains Poe's often-used theme of the death of a beautiful woman, which he called the "most poetical topic in the world".[9][10]

Dupin's method[]

Poe defines Dupin's method, ratiocination, using the example of a card player: "the extent of information obtained; lies not so much in the validity of the inference as in the quality of the observation."[11][12] Poe then provides a narrative example where Dupin explains how he knew the narrator was thinking about the actor Chantilly.[13][14] Dupin then applies his method to the solving of this crime.

Dupin's method emphasizes the importance of reading and the written word. The newspaper accounts pique his curiosity; he learns about orangutans from a written account by "Cuvier" — likely Georges Cuvier, the French zoologist. This method also engages the reader, who follows along by reading the clues himself.[15] Poe also emphasizes the power of the spoken word. When Dupin asks the sailor for information about the murders, the sailor himself acts out a partial death: "The sailor's face flushed up as if he were struggling with suffocation... the next moment he fell back into his seat, trembling violently, and with the countenance of death itself."[16]

Literary significance and reception[]

Poe biographer Jeffrey Meyers sums up the significance of "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" by saying it "changed the history of world literature."[2] Often cited as the first detective fiction story, the character of Dupin became the prototype for many future fictional detectives, including Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes and Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot. The genre is distinctive from a general mystery story in that the focus is on analysis.[17] Poe's role in the creation of the detective story is reflected in the Edgar Awards, given annually by the Mystery Writers of America.[18]

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" also established many tropes that would become common elements in mystery fiction: the eccentric but brilliant detective, the bumbling constabulary, the first-person narration by a close personal friend. Poe also portrays the police in an unsympathetic manner as a sort of foil to the detective.[19] Poe also initiates the storytelling device where the detective announces his solution and then explains the reasoning leading up to it.[20] It is also the first locked room mystery in detective fiction.[21]

Upon its release, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" and its author were praised for the creation of a new profound novelty.[9] The Pennsylvania Inquirer printed that "it proves Mr Poe to be a man of genius... with an inventive power and skill, of which we know no parallel."[21] Poe, however, downplayed his achievement in a letter to Philip Pendleton Cooke:[22]

These tales of ratiocination owe most of their popularity to being something in a new key. I do not mean to say that they are not ingenious – but people think them more ingenious than they are – on account of their method and air of method. In the "Murders in the Rue Morgue", for instance, where is the ingenuity in unraveling a web which you yourself... have woven for the express purpose of unraveling?"[3]

Modern readers are occasionally put off by Poe's violation of an implicit narrative convention: readers should be able to guess the solution as they read. The twist ending, however, is a sign of "bad faith" on Poe's part because readers would not reasonably include an orangutan on their list of potential murderers.[23]

Inspiration[]

The word detective did not exist at the time Poe wrote "The Murders in the Rue Morgue",[9] though there were other stories that featured similar problem-solving characters. Das Fräulein von Scuderi (1819), by E. T. A. Hoffmann, in which Mlle. de Scuderi, a kind of 19th-century Miss Marple, establishes the innocence of the police's favorite suspect in the murder of a jeweler, is sometimes cited as the first detective story.[24] Other forerunners include Voltaire's Zadig (1748), with a main character who performs similar feats of analysis,[1] themselves borrowed from The Three Princes of Serendip, an Italian rendition of Amir Khusro's "Hasht-Bihisht".[25]

Poe may also have been expanding on previous analytical works of his own including the essay on "Maelzel's Chess Player" and the comedic "Three Sundays in a Week".[21] As for the twist in the plot, Poe was likely inspired by the crowd reaction to an orangutan on display at the Masonic Hall in Philadelphia in July 1839.[2] Poe might have picked up some of the relevant biological knowledge from collaborating with Thomas Wyatt,[26] with Poe furthermore linking "his narrative with the subject of evolution, especially the studies done by Cuvier",[27] possibly also influenced by the studies conducted by Lord Monboddo,[28] though it has been argued that Poe's information was "more literary than scientific".[29]

The name of the main character may have been inspired from the "Dupin" character in a series of stories first published in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine in 1828 called "Unpublished passages in the Life of Vidocq, the French Minister of Police".[30] Poe would likely have known the story, which features an analytical man who discovers a murderer, though the two plots share little resemblance. Murder victims in both stories, however, have their neck cut so badly that the head is almost entirely removed from the body.[31] Dupin actually mentions Vidocq by name, dismissing him as "a good guesser".[32]

Publication history[]

Poe originally titled the story "Murders in the Rue Trianon" but renamed it to better associate with death.[33] "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" first appeared in Graham's Magazine in April 1841 while Poe was working as an editor. He was paid an additional $56 for it — an unusually high figure; he was only paid $9 for "The Raven".[34] In 1843, Poe had the idea to print a series of pamphlets with his stories entitled The Prose Romances of Edgar A. Poe. He printed only one, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" oddly collected with the satirical "The Man That Was Used Up". It sold for 12 and a half cents.[35] This version included 52 changes from the original text from Graham's, including the new line: "The Prefect is somewhat too cunning to be profound", a change from the original "too cunning to be acute".[36] "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" was also reprinted in Wiley & Putnam's collection of Poe's stories simply called Tales. Poe did not take part in selecting which tales would be collected.[37]

Poe's sequel to "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" was "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt", first serialized in December 1842 and January 1843. Though subtitled "A Sequel to 'The Murders in the Rue Morgue'", "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" shares very few common elements with "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" beyond the inclusion of C. Auguste Dupin and the Paris setting.[38] Dupin reappeared in "The Purloined Letter", which Poe called "perhaps the best of my tales of ratiocination" in a letter to James Russell Lowell in July 1844.[39]

The original manuscript of "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" which was used for its first printing in Graham's Magazine was discarded in a wastebasket. An apprentice at the office, J. M. Johnston, retrieved it and left it with his father for safekeeping. It was left in a music book, where it survived three house fires before being bought by George William Childs. In 1891, Childs presented the manuscript, re-bound with a letter explaining its history, to Drexel University.[40] Childs had also donated $650 for the completion of Edgar Allan Poe's new grave monument in Baltimore, Maryland in 1875.[41]

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" was one of the earliest of Poe's works to be translated into French. Between June 11 and June 13, 1846, "Un meurtre sans exemple dans les Fastes de la Justice" was published in La Quotidienne, a Paris newspaper. Poe's name was not mentioned and many details, including the name of the Rue Morgue and the main characters ("Dupin" became "Bernier"), were changed.[42] On October 12, 1846, another uncredited translation, renamed "Une Sanglante Enigme", was published in Le Commerce. The editor of Le Commerce was accused of plagiarizing the story from La Quotidienne. The accusation went to trial and the public discussion brought Poe's name to the attention of the French public.[42]

Adaptations[]

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" has been adapted for radio, film and television many times.

- The 1908 American silent film Sherlock Holmes in the Great Murder Mystery was an adaptation of the story, with Dupin replaced by Sherlock Holmes. The film is lost and the director and cast are unknown.

- The story was adapted in a short silent film made in 1914.[43]

- The first full-length version was Murders in the Rue Morgue by Universal Pictures in 1932, directed by Robert Florey and starring Bela Lugosi, Leon Ames and Sidney Fox, with Arlene Francis.[17] The film bears little resemblance to the original story.

- Another adaptation, Phantom of the Rue Morgue, was released in 1954 by Warner Brothers, directed by Roy Del Ruth and starring Karl Malden and Patricia Medina.

- A TV movie made by Syndicated in 1968, The Murders in the Rue de Morgue, is an adaptation by James MacTaggart, starring , Charles Kay and .

- A film in 1971 directed by Gordon Hessler with the title Murders in the Rue Morgue had little to do with the Poe story.

- On January 7, 1975, a radio-play version was broadcast on CBS Radio Mystery Theater.

- A made-for-TV movie, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, aired in 1986. It was directed by Jeannot Szwarc and starred George C. Scott, Sebastian Roché, Rebecca De Mornay, Ian McShane, and Val Kilmer.

- It has also been adapted as a video game by Big Fish Games for their "Dark Tales" franchise under the title "Dark Tales: Edgar Allan Poe's Murders in the Rue Morgue".[44]

- Murders in the Rue Morgue, and The Gold Bug (1973), a simplified version by Robert James Dixson, was published by Regents Pub. Co.

- British heavy metal band Iron Maiden has a song on their 1981 album Killers titled Murders in Rue Morgue, the lyrics are told from the perspective of a man stumbling upon two bodies and then fleeing the scene after being falsely accused of committing the murders (Something which did not happen in the story).

- The first volume (1999) of Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's comic book series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen retcons the murders to have been perpetrated by Mr. Hyde, and establishes that Dupin (also a character of the story) was wrong. Also, the story states that the murders have restarted, with one of the victims being Anna Coupeau from Émile Zola's Nana.

- In 2004, Dark Horse Comics released a one-shot comic book Van Helsing: From Beneath the Rue Morgue using a murder scene from Poe's story.

- Morgue Street is a 2012 short film directed by starring and Désirée Giorgetti.[45][46]

See also[]

- Rue Morgue (magazine)

- Rue Morgue Radio

References[]

- ^ a b c d Silverman 1991, p. 171

- ^ a b c Meyers 1992, p. 123

- ^ a b Quinn 1998, p. 354

- ^ Whalen 2001, p. 86

- ^ Cleman 1991, p. 623

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 312

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 172

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 75

- ^ a b c Silverman 1991, p. 173

- ^ Hoffman 1972, p. 110

- ^ Poe 1927, p. 79

- ^ Harrowitz 1984, pp. 186–187

- ^ Poe 1927, pp. 82–83

- ^ Harrowitz 1984, pp. 187–192

- ^ Thoms 2002, pp. 133–134

- ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 120

- ^ a b Sova 2001, pp. 162–163

- ^ Neimeyer 2002, p. 206

- ^ Van Leer 1993, p. 65

- ^ Cornelius 2002, p. 33

- ^ a b c Silverman 1991, p. 174

- ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 119

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 68

- ^ Booker 2004, p. 507

- ^ Merton 2006, p. 16

- ^ Pérez Arranz 2018, pp. 112–114

- ^ Autrey 1977, p. 193

- ^ Autrey 1977, p. 188

- ^ Laverty 1951, p. 221

- ^ Cornelius 2002, p. 31

- ^ Ousby 1972, p. 52

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 311

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 162

- ^ Ostram 1987, pp. 39, 40

- ^ Ostram 1987, p. 40

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 399

- ^ Quinn 1998, pp. 465–466

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 165

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 430

- ^ Boll 1943, p. 302

- ^ Miller 1974, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b Quinn 1998, p. 517

- ^ "The Murders in the Rue Morgue". August 1914.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. (2012). American Literature on Stage and Screen. NC, USA: McFarland. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7864-6842-3.

- ^ "Alberto Viavattene".

- ^ "Federica Tommasi".

Sources[]

- Autrey, Max L. (May 1977). "Edgar Allan Poe's Satiric View of Evolution". Extrapolation. 18 (2): 186–199. doi:10.3828/extr.1977.18.2.186.

- Boll, Ernest (May 1943). "The Manuscript of 'The Murders in the Rue Morgue' and Poe's Revisions". Modern Philology. 40 (4): 302–315. doi:10.1086/388587. S2CID 161841024.

- The Seven Basic Plots. Booker, Christopher (2004). The Seven Basic Plots. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-8037-8.

- Cleman, John (December 1991). "Irresistible Impulses: Edgar Allan Poe and the Insanity Defense". American Literature. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 63 (4): 623–640. doi:10.2307/2926871. JSTOR 2926871.

- Cornelius, Kay (2002), "Biography of Edgar Allan Poe", in Harold Bloom (ed.), Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7910-6173-2

- Harrowitz, Nancy (1984), "The Body of the Detective Model: Charles S. Peirce and Edgar Allan Poe", in Umberto Eco; Thomas Sebeok (eds.), The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce, Bloomington, IN: History Workshop, Indiana University Press, pp. 179–197, ISBN 978-0-253-35235-4. Harrowitz discusses Dupin's method in the light of Charles Sanders Peirce's logic of making good guesses or abductive reasoning.

- Hoffman, Daniel (1972). Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2321-8.

- Kennedy, J. Gerald (1987). Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03773-9.

- Laverty, Carol Dee (1951). Science and Pseudo-Science in the Writings of Edgar Allan Poe (PhD). Duke University.

- Merton, Robert K. (2006). The travels and adventures of serendipity : a study in sociological semantics and the sociology of science (Paperback ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0691126302.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1038-6.

- Miller, John C. (December 1974). "The Exhumations and Reburials of Edgar and Virginia Poe and Mrs. Clemm". Poe Studies. vii (2): 46–47. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1974.tb00236.x.

- Neimeyer, Mark (2002). "Poe and Popular Culture". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–224. ISBN 978-0-521-79727-6.

- Pérez Arranz, Cristina (2018). Edgar Allan Poe desde la imaginación científica (PhD). Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (1927), Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, New York: Walter J. Black

- Ostram, John Ward (1987). "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards". Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. pp. 37–47.

- Ousby, Ian V. K. (December 1972). "The Murders in the Rue Morgue and 'Doctor D'Arsac': A Poe Source". Poe Studies. V (2): 52. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1972.tb00201.x.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998). Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5730-0.

- Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997). The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092331-0.

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work (Paperback ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-8160-4161-9.

- Thoms, Peter (2002). "Poe's Dupin and the Power of Detection". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–147. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- Van Leer, David (1993). "Detecting Truth: The World of the Dupin Tales". In Silverman, Kenneth (ed.). The American Novel: New Essays on Poe's Major Tales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–92. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7.

- Whalen, Terance (2001). "Poe and the American Publishing Industry". In Kennedy, J. Gerald (ed.). A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512150-6.

External links[]

- Full text on PoeStories.com with hyperlinked vocabulary words.

- First appearance in Graham's Magazine, April 1841, p. 166.

The Murders in the Rue Morgue public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Murders in the Rue Morgue public domain audiobook at LibriVox- History of publications at the Edgar Allan Poe Society online

- 1841 short stories

- Short stories by Edgar Allan Poe

- Detective fiction short stories

- Short stories set in Paris

- Locked-room mysteries

- Works originally published in Graham's Magazine

- Short stories adapted into films

- Fictional orangutans