The Cotton Club (film)

| The Cotton Club | |

|---|---|

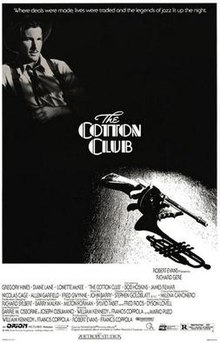

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by | William Kennedy Francis Ford Coppola |

| Story by | William Kennedy Francis Ford Coppola Mario Puzo |

| Based on | The Cotton Club by James Haskins |

| Produced by | Robert Evans |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stephen Goldblatt |

| Edited by | Barry Malkin Robert Q. Lovett |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $58 million |

| Box office | $25.9 million[1] |

The Cotton Club is a 1984 American crime drama film co-written and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. The story centers on the Cotton Club a Harlem jazz club in the 1930s. The movie stars Richard Gere, Gregory Hines, Diane Lane, and Lonette McKee. The supporting cast included Bob Hoskins, James Remar, Nicolas Cage, Allen Garfield, Gwen Verdon and Fred Gwynne.

The film was noted for its over-budget production costs, and took a total of five years to make.

Despite being a disappointment at the box-office, the film received generally positive reviews. It was nominated for several awards, including Golden Globes for Best Director and Best Picture (Drama) and Oscars for Best Art Direction (Richard Sylbert, George Gaines) and Best Film Editing.

Plot[]

A musician named Dixie Dwyer begins working with mobsters to advance his career but falls in love with Vera Cicero, the girlfriend of gangland kingpin Dutch Schultz.

A dancer from Dixie's neighborhood, Sandman Williams, is hired with his brother by The Cotton Club, a jazz club where most of the performers are black and the customers are white. Owney Madden, a mobster, owns the club and runs it with his right-hand man, Frenchy.

Dixie becomes a Hollywood film star, thanks to the help of Madden and the mob but angering Schultz. He also continues to see Schultz's gun moll, Vera Cicero, whose new nightclub has been financed by the jealous gangster.

In the meantime, Dixie's ambitious younger brother Vincent becomes a gangster in Schultz's mob and eventually a public enemy, holding Frenchy as a hostage.

Sandman alienates his brother Clay at The Cotton Club by agreeing to perform a solo number there. While the club's management interferes with Sandman's romantic interest in Lila, a singer, its cruel treatment of the performers leads to an intervention by Harlem criminal 'Bumpy' Rhodes on their behalf.

Dutch Schultz is violently dealt with by Madden's men while Dixie and Sandman perform on The Cotton Club's stage.

Cast[]

- Richard Gere as Michael "Dixie" Dwyer

- Gregory Hines as Delbert "Sandman" Williams

- Diane Lane as Vera Cicero

- Lonette McKee as Lila Rose Oliver

- Bob Hoskins as Owney Madden

- James Remar as Dutch Schultz

- Nicolas Cage as Vincent Dwyer

- Allen Garfield as Otto Berman

- Fred Gwynne as Frenchy Demange

- Gwen Verdon as Tish Dwyer

- Lisa Jane Persky as Frances Flegenheimer

- Maurice Hines as Clayton "Clay" Williams

- Julian Beck as Sol Weinstein

- Joe Dallesandro as Charles "Lucky" Luciano

- Larry Fishburne as Bumpy Rhodes

- Tom Waits as Irving Starck

- John P. Ryan as Joe Flynn

- Glenn Withrow as Ed Popke

- Jennifer Grey as Patsy Dwyer

- Woody Strode as Holmes

- Diane Venora as Gloria Swanson

- Tucker Smallwood as Kid Griffin

- Bill Cobbs as Big Joe Ison

- Rosalind Harris as Fanny Brice

- Mark Margolis as Charlie Workman

- Larry Marshall as Cab Calloway

Production[]

Inspired to make The Cotton Club by a picture-book history of the nightclub by James Haskins, Robert Evans was the film's original producer and also wanted to direct.[2] He hired William Kennedy and Francis Ford Coppola to re-write Mario Puzo's story and screenplay. Evans eventually decided that he did not want to direct the film and asked Coppola at the last minute.[3] Richard Sylbert said that he told Evans not to hire Coppola because "he resents being in the commercial, narrative, Hollywood movie business".[4] Coppola said that he had letters from Sylbert asking him to work on the film because Evans was crazy. Coppola also said that "Evans set the tone for the level of extravagance long before I got there".[4]

Coppola accepted the jobs as screenwriter and then director because he needed the money – he was deeply in debt from making One from the Heart with his own money.[5] By the time Evans decided not to direct and brought in Coppola, at least $13 million had already been committed.[4] Las Vegas casino owners Edward and Fred Doumani put $30 million into the film. Other financial backers included Arab arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, and vaudeville promoter Roy Radin, who was murdered in May 1983 by a drug dealer associate who felt she was cut out of profits from the film.[6] According to William Kennedy in an interview with Vanity Fair, the budget of the film was $47 million. However, Coppola told the head of Gaumont Film Company, Europe's largest distribution and production company, that he thought the film might cost $65 million.[2]

According to Splitsider, Richard Pryor was considered for the role of Sandman Williams.[7] Robert Evans wanted to cast his friend Alain Delon in a two-scene role as Lucky Luciano but this did not occur.[8] The role of Luciano was instead portrayed by Joe Dallesandro, starting the dramatic film career for the former Warhol Superstar.

Author Mario Puzo was the original screenwriter and was eventually replaced by William Kennedy,[5] who wrote a rehearsal script in eight days which the cast used for three weeks prior to shooting. According to actor Gregory Hines, a three-hour film was shot during rehearsals.[2]

Over 600 people built sets, created costumes and arranged music at a reported $250,000 a day.[2]

From July 15 to August 22, 1983, twelve scripts were produced, including five during one 48-hour non-stop weekend. Kennedy estimates that between 30 and 40 scripts were turned out.[2]

On June 7, 1984, Victor L. Sayyah filed a lawsuit against the Doumani brothers, their lawyer David Hurwitz, Evans and Orion Pictures for fraud and breach of contract.[3] Sayyah invested $5 million and said that he had little chance of recouping his money because the budget escalated from $25 to $58 million. He accused the Doumanis of forcing out Evans and said that an Orion loan to the film of $15 million unnecessarily increased the budget. Evans, in turn, sued Edward Doumani to keep from acting as general partner on the film.[3]

Music[]

The soundtrack for the film was written by John Barry. It released on December 14, 1984, via Geffen Records. The album won the Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Big Band in 1986.[9]

Release[]

Home media[]

Embassy Home Entertainment paid a record $4.7 million for North America home video rights.[10] The film appeared on videotape and videodisc in April 1985. It was the first to use the Macrovision copy protection system, on VHS and Betamax only.[11]

Director's cut[]

In 2015, Coppola found an old Betamax video copy of his original cut that ran 25 minutes longer. When originally editing the picture, he acquiesced to distributors who wanted a shorter film with a different structure. Between 2015 and 2017, Coppola spent over $500,000 of his own money to restore the film to the original cut. This version, titled The Cotton Club: Encore and running 139 minutes, debuted at the Telluride Film Festival on September 1, 2017.[12] Lionsgate (owner of the Zoetrope Corporation backlog, and working in association with original studio Orion Pictures) released that version theatrically, and on DVD and Blu-ray in the fall of 2019.

The Film Stage gave The Cotton Club: Encore a rating of A-, while Rolling Stone described the result of this version as 'eye-opening'.[13][14]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The Cotton Club was released on December 14, 1984, in the United States and Canada on 808 screens and grossed $2.9 million on its opening weekend, fifth place behind Beverly Hills Cop, Dune, City Heat and 2010.[15][16] Evans took the blame for hiring Coppola while Coppola responded that if he had not been hired, the film would have never been made. Evans said that Coppola made the budget escalate dramatically by rejecting the script, hiring his own crew, and falling behind schedule.[16] The film was a commercial failure, grossing just under $26 million against a $58 million budget.

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has a 77% rating based on 30 reviews. The site's consensus states: "Energetic and brimming with memorable performers, The Cotton Club entertains with its visual and musical pizazz even as its plot only garners polite applause."[17] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 68% based on reviews from 14 critics.[18]

The film appeared on both Siskel and Ebert's best of 1984.[19]

Diane Lane was nominated for the Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Supporting Actress category (also for her work in Streets of Fire), ultimately losing to Lynn-Holly Johnson for Where the Boys Are '84.

References[]

- ^ The Cotton Club at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Scott, Jay (November 12, 1984). "Making of Cotton Club: A Legend of its Own". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Harmetz, Aljean (June 10, 1984). "Cotton Club Investor Sues Partners in Film". New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kroll, Jack (December 24, 1984). "Harlem on My Mind". Newsweek.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gussow, Michael (March 22, 1984). "Parting Film Shots: Coppola and Dutch". New York Times.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (March 10, 2020). "Ten Billionaires Who Were Stung by Hollywood". Filmink.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (September 1, 2011). "The Lost Roles of Richard Pryor". Splitsider. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (September 3, 1982). "Hollywood: French actor Delon will play Lucky role". Chicago Tribune. p. c5.

- ^ "The Cotton Club – John Barry | Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Bierbaum, Tom (December 21, 1984). "IVE Pays $2 Mil For Homevideo Rights To '1984'". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ De Atley, Richard (September 7, 1985). "VCRs put entertainment industry into fast-forward frenzy". The Free Lance-Star. Associated Press. pp. 12–TV. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (September 1, 2017). "Francis Ford Coppola: Why He Spent $500K to Restore His Most Troubled Film, 'The Cotton Club'". IndieWire. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ NYFF Review: With 'The Cotton Club Encore', Francis Ford Coppola Brings Grandeur to New Reworking

- ^ ‘The Cotton Club’: Francis Ford Coppola's Mangled Epic Gets an Encore Rolling Stone

- ^ "Domestic 1984 Weekend 50". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Salmans, Sandra (December 20, 1984). "Cotton Club is Neither a Smash Nor a Disaster". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Cotton Club". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ "The Cotton Club". Metacritic. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Siskel and Ebert Top Ten Lists (1969–1998)". Innermind.com. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Further reading[]

- Parish, James Robert (2006). Fiasco – A History of Hollywood's Iconic Flops. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 359 pages. ISBN 978-0-471-69159-4.

External links[]

- The Cotton Club at IMDb

- The Cotton Club at AllMovie

- The Cotton Club at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Roger Ebert review Archived September 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- 1984 films

- English-language films

- 1980s musical films

- 1984 crime drama films

- American films

- American crime drama films

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films about the Irish Mob

- Jazz films

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films with screenplays by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- American Zoetrope films

- Orion Pictures films

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Harlem

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films produced by Robert Evans

- Films about the American Mafia

- Films about African-American organized crime

- Films about Jewish-American organized crime

- Cultural depictions of Lucky Luciano

- Cultural depictions of Dutch Schultz

- Cultural depictions of Cab Calloway