Finian's Rainbow (1968 film)

| Finian's Rainbow | |

|---|---|

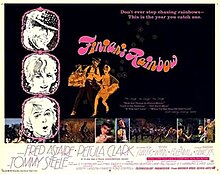

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by | E.Y. Harburg Fred Saidy |

| Based on | Finian's Rainbow by E.Y. Harburg Fred Saidy |

| Produced by | Joseph Landon |

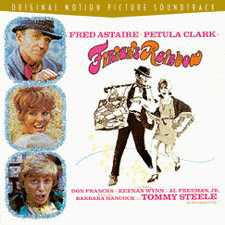

| Starring | Fred Astaire Petula Clark Don Francks Keenan Wynn Al Freeman Jr. Barbara Hancock Tommy Steele |

| Cinematography | Philip H. Lathrop |

| Edited by | Melvin Shapiro |

| Music by | Burton Lane (music) E.Y. Harburg (lyrics) Ray Heindorf (music score) |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts |

Release date |

|

Running time | 145 minutes |

| Countries | Ireland United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million |

| Box office | $11.6 million |

Finian's Rainbow is a 1968 musical fantasy film directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Fred Astaire and Petula Clark. The screenplay by E.Y. Harburg and Fred Saidy is based on their 1947 stage musical of the same name. An international co-production of Ireland and the United States, the film follows an Irishman and his daughter who steal a leprechaun's magic pot of gold and emigrate to the U.S., where they become involved in a dispute between rural landowners and a greedy, racist U.S. senator.

The film was nominated for two Academy Awards, five Golden Globe Awards, and a Writers Guild of America Award.

Plot[]

A lovable rogue named Finian McLonergan absconds from his native Ireland with a crock of gold secreted in a carpetbag, plus his daughter Sharon in tow. His destination is Rainbow Valley in the (fictional) state of Missitucky, where he plans to bury his treasure in the mistaken belief that, given its proximity to Fort Knox, it will multiply.

Hot on Finian's heels is the leprechaun Og, desperate to recover his stolen crock before he turns human. Among those involved in the ensuing shenanigans are Woody Mahoney, a ne'er-do-well dreamer who woos Sharon; Woody's mute sister Susan, who expresses herself in dance; Woody's good friend and business partner Howard, an African-American botanist determined to develop a tobacco/mint hybrid; and bombastic Senator Billboard Rawkins, who wears his bigotry as if it were a badge of honor.

Complications arise when Rawkins, believing there is gold in Rainbow Valley, attempts to seize the land from the people who live there and makes some racial slurs while doing so. Sharon furiously wishes he would turn black himself and, because she happens to unknowingly be standing on the spot where the magical crock of gold (which is capable of granting three wishes) is buried, Rawkins does exactly that. Rawkins' dog, who has been trained to attack black people, chases him off into the woods. Later, the sheriff returns with the district attorney, who threatens to charge Sharon with witchcraft unless Rawkins is produced.

Rawkins runs into Og in the woods and tells him that a witch changed him from a white man to black. Seeing that the change of skin color did nothing to alter his hateful racism, Og casts a spell to make Rawkins more open-minded.

The townspeople gather in the barn for the wedding of Sharon and Woody, but the sheriff, his deputies, and the district attorney interrupt the ceremony and arrest Sharon for witchcraft. Finian convinces them that Sharon can change Rawkins back to white overnight, and they lock Sharon and Woody in the barn until daybreak. To save his daughter, Finian tries to find the crock of gold he buried, unaware that Susan has discovered it and moved it. Og meets with Susan on the bridge under which she has hidden the gold and wishes she could talk. When she begins to speak, Og realizes he must be standing above the crock.

As the district attorney sets the barn on fire with Sharon and Woody locked inside, Og debates whether or not he should use the gold's final wish to save Sharon by turning the senator white again, even if it would mean the crock would lose its magic, the gold would disappear, and he would become fully mortal. After a passionate kiss from Susan, he decides it might not be so bad to be a human and wishes for Rawkins to be white once more. Sharon and Woody are released from the burning barn, and it is discovered that Howard's mentholated tobacco experiments have at last been successful, ensuring financial success for all the poor people of Rainbow Valley, both white and black. Sharon and Woody are wed, and everyone bids a fond farewell to Finian, who leaves Rainbow Valley in search of his own rainbow.

Cast[]

- Fred Astaire as Finian McLonergan

- Petula Clark as Sharon McLonergan

- Tommy Steele as Og

- Don Francks as Woody Mahoney

- Keenan Wynn as Senator Billboard Rawkins

- Barbara Hancock as Susan the Silent

- Al Freeman Jr. as Howard

- Ronald Colby as Buzz Collins

- Dolph Sweet as Sheriff

- Wright King as District Attorney

- Louil Silas as Henry

- Uncredited cast

- Brenda Arnau as Sharecropper 'Necessity'

- Roy Glenn as Passion Pilgrim Gospeleer quartet member

- Jester Hairston as Passion Pilgrim Gospeleer quartet member

- Vince Howard as Geologist #1

- Avon Long as Passion Pilgrim Gospeleer quartet member

- Gregory Hines as child extra

Production[]

Development[]

Since the musical was such a success on stage, there had always been interest in filming it. MGM was interested in filming it in 1948 as a vehicle for Mickey Rooney. However, Harburg set the price for the rights at $1 million and wanted creative control.[1]

For a time, a German company wanted to make the film adaptation. In 1954, the Distributors Corporation of America tried to make it as an animated film. A soundtrack of the score was recorded by several stars, but the film was not completed. In 1958, the authors of the musical teamed with Sidney Buchman to produce a film independently, but this project did not proceed.[2]

In 1960, the film rights were held by Marvin Rothenberg, who wanted Michael Gordon to direct and Debbie Reynolds to star. It was announced the film would be budgeted at $2 million and be released by United Artists,[2][3] but the film did not eventuate.[4]

Harburg stated in 1960 that he was told part of the reason it was so difficult to get a film version made was Hollywood was scared of fantasy musicals.[5] Another reason was the McCarthyism of the period.[1]

In 1965, Harold Hecht bought the film rights and hired Harburg and Saidy to write a script and some new songs. Hecht said he intended to film in nine months. "This time we really mean business," said Harburg. "We've gotten a substantial deal and participation in money and production. Up until now Finian has been making so much money on the road that we didn't want to kill the goose laying all those golden eggs. But you become more idealistic as you grow older and you tend to stop thinking about yourself."[6] Dick Van Dyke was considered to play the role of Finian, but financial problems caused the filming to be postponed, and Van Dyke dropped out of consideration.[7][full citation needed]

Warner Bros.[]

In September 1966, Warner Bros. announced it had the rights and would make a film produced by Joseph Landon and starring Fred Astaire, with the aim to get Tommy Steele as the leprechaun. The budget was expected to be $4 million.[8][9] Francis Ford Coppola was signed as director in February 1967.[10] Steele was then confirmed as the leprechaun, although Robert Morse had expressed interest.[11]

With Camelot having proven to be more costly than anticipated, and its commercial success still undetermined because it had not been released yet, Jack L. Warner was having second thoughts about undertaking another musical project, but when he saw Petula Clark perform on her opening night at the Coconut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, he knew he had found the ideal Sharon.[12] He decided to forge ahead and hoped for the best despite his misgivings about having nearly-novice "hippie" director Francis Ford Coppola at the helm. Although Clark had made many films in the 1940s and 1950s in her native Great Britain, this was her first starring role in 10 years, and her first film appearance since rising to international fame with "Downtown" four years earlier.

Fred Astaire's last movie musical before this film had been Silk Stockings 11 years earlier. He had concentrated on his TV specials in the interim, but was persuaded, at the age of 69, to return to the big screen. Given his status as a screen legend and to accommodate his talents, the role of Finian was given a musical presence it had not had on stage, and Astaire was given top billing, rather than the part's original third billing.

While a construction crew transformed more than nine acres of back lot into Rainbow Valley, complete with a narrow gauge railway, schoolhouse, general store, post office, houses, and barns, Coppola spent five weeks rehearsing the cast, and, before principal photography began, a complete performance of the film was presented to an audience on a studio sound stage.[13] In the liner notes she wrote for the 2004 Rhino Records limited, numbered edition CD release of the soundtrack, Clark recalls that old-Hollywood Astaire was befuddled by Coppola's contemporary methods of film-making and balked at dancing in "a real field with cow dung and rabbit holes." Although he acquiesced to filming a sequence in Napa Valley near Coppola's home, the bulk of the movie was shot on studio sound stages and the back lot, leaving the finished film with jarring contrasts between reality and make-believe.[12]

Clark was nervous about her first Hollywood movie, and particularly concerned about dancing with old pro Astaire. He later confessed he was just as worried about singing with her.[12] The film was partially choreographed by Astaire's long-time friend and collaborator Hermes Pan, though he was fired by Coppola during filming.[14] Finian's Rainbow proved to be Astaire's last major movie musical, although he went on to dance with Gene Kelly during the linking sections of That's Entertainment, Part 2.

Clark recalls that Coppola's approach was at odds with the subject matter. "Francis...wanted to make it more real. The problem with Finian's Rainbow is that it's sort of like a fairy tale...so trying to make sense of it was a very delicate thing."[12] Coppola opted to fall somewhere in the middle, with mixed results. Updating the story line was limited to changing Woody from a labor organizer to the manager of a sharecroppers' cooperative, making college-student Howard a research botanist, and a few minor changes to the lyrics in the Burton Lane–E.Y. Harburg score, such as changing a reference to Carmen Miranda to Zsa Zsa Gabor. Other than that, the plot remains entrenched in an era that predates the Civil Rights Movement.

Because preview audiences found the film overly long, the musical number "Necessity" was deleted before its release, although the song remains on the soundtrack album. It can be heard as background music when Senator Rawkins first shows up in Rainbow Valley in his attempt to buy Finian out.

In August 2012, Clark told the BBC Radio 4 show The Reunion that she and her fellow cast members smoked marijuana during the filming of the movie. "There was a lot of Flower Power going on," she said.[15]

Musical sequences[]

- Overture

- Look to the Rainbow

- This Time of the Year

- How Are Things in Glocca Morra?

- Look to the Rainbow (Reprise)

- Old Devil Moon

- Something Sort of Grandish

- If This Isn't Love

- (That) Great Come-and-Get-It-Day

- Entr'acte

- When the Idle Poor Become the Idle Rich

- Rain Dance Ballet

- The Begat

- When I'm Not Near the Girl I Love

- How Are Things in Glocca Morra? (Reprise)

- Exit Music

Release[]

The film premiered on October 9, 1968 at the newly opened Warner Penthouse Theatre in New York City.[16]

Critical reception[]

Released in major cities as a roadshow presentation, complete with intermission, at a time when the popularity of movie musicals was on the wane, the film was dismissed as inconsequential by many critics, who found Astaire's obviously frail and aged appearance shocking and Steele's manic performance annoying. In the New York Times, Renata Adler described it as a "cheesy, joyless thing" and added "there is something awfully depressing about seeing Finian's Rainbow...with Fred Astaire looking ancient, far beyond his years, collapsed and red-eyed...it is not just that the musical is dated...it is that it has been done listlessly and even tastelessly."[17]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, on the other hand, thought it was "the best of the recent roadshow musicals...Since The Sound of Music, musicals have been...long, expensive, weighed down with unnecessary production values and filled with pretension...Finian's Rainbow is an exception...it knows exactly where it's going, and is getting there as quickly and with as much fun as possible...it is the best-directed musical since West Side Story. It is also enchanting, and that's a word I don't get to use much...it is so good, I suspect, because Astaire was willing to play it as the screenplay demands...he...created this warm old man...and played him wrinkles and all. Astaire is pushing 70, after all, and no effort was made to make him look younger with common tricks of lighting, makeup and photography. That would have been unnecessary: He has a natural youthfulness. I particularly want to make this point because of the cruel remarks on Astaire's appearance in the New York Times review by Renata Adler. She is mistaken."[18]

Time Out London calls it an "underrated musical...the best of the latter-day musicals in the tradition of Minnelli and MGM."[19]

Highly praised by all was Petula Clark, whom Ebert described as "a surprise. I knew she could sing, but I didn't expect much more. She is a fresh addition to the movies: a handsome profile, a bright personality, and a singing voice as unique in its own way as Streisand's." John Mahoney of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Clark "invites no comparisons, bringing to her interpretation of Sharon her own distinctive freshness and form of delivery."[13] In the New York Daily News, Wanda Hale cited her "winsome charm which comes through despite a somewhat reactive role."[13] Joseph Morgenstern of Newsweek wrote that she "looks lovely" and "sings beautifully, with an occasional startling reference to the phrasing and timbre of Ella Logan's original performance."[13] Variety observed "Miss Clark gives a good performance and she sings the beautiful songs like a nightingale."[13] Clearly, in the United States at least, Clark was known only as a singer, although she had appeared as an actress in British films since she was a child.

In its first two months, the film earned $5.1 million in rentals in North America,[20] ending its worldwide run with $11.6 million.[21]

The Coen brothers have expressed that the film is among their favorite films: "I remember when we worked with Nicolas Cage on Raising Arizona, we talked about his uncle, Francis Ford Coppola, and told him that Finian's Rainbow, which hardly anyone has ever seen, was one of our favorite films. He told his uncle, who I think has considered us deranged ever since."[22]

Awards and honors[]

The film was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, but lost to Oliver!; Petula Clark was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy, but lost to Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl; Fred Astaire was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy, but lost to Ron Moody in Oliver!; and Barbara Hancock was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture, but lost to Ruth Gordon in Rosemary's Baby.

Ray Heindorf was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Score – Adaptation or Treatment, but lost to Johnny Green for Oliver!, and M.A. Merrick and Dan Wallin were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound, but lost to Jim Groom for Oliver![23]

E.Y. Harburg and Fred Saidy were nominated for Best Written American Musical by the Writers Guild of America.

The song "How Are Things in Glocca Morra?" was nominated by the American Film Institute in its 2004 list AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs.[24]

Home media[]

The film was released on DVD on March 15, 2005. Presented in anamorphic widescreen format, this release captures all of Astaire's footwork, much of which was unseen at the time of the original release because it had been cropped out during a conversion from 35mm to 70mm film.[citation needed] There are audio tracks in English and French, with both the dialogue and songs translated into the latter language (fluent in French, Clark was the sole cast member to record her own songs for the foreign version); a commentary track by Francis Ford Coppola, who focuses mostly on the film's shortcomings; a featurette on the world premiere of the film; and the original theatrical trailer.

The film was released on Blu-ray on March 7, 2017.[25]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Philip K. Scheuer Special to the (Dec 26, 1967). "Deck Is Stacked Against Broadway". Los Angeles Times. p. C7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b A.H. WEILER (Apr 17, 1960). "VIEW FROM A LOCAL VANTAGE POINT". New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (Jan 8, 1960). "Director's First Comedy a Smash: They Told Gordon He Couldn't Make One---Till 'Pillow Talk'!". Los Angeles Times. p. A7.

- ^ A.H. WEILER (Dec 25, 1960). "GREAT EXPECTATIONS: Or, the Annual Survey of a Few Fine Plans That Failed to Materialize". New York Times. p. X9.

- ^ John Crosby. (May 22, 1960). "Age of the Unthinking' Blamed on Broadcasters". The Washington Post. p. G13.

- ^ A.H. WEILER (Nov 7, 1965). "Smutty Nose to 93rd St.: More About Movies". New York Times. p. X11.

- ^ (Source: "The Films of Fred Astaire")

- ^ Martin, Betty (Sep 28, 1966). "MOVIE CALL SHEET: Warners to Film 'Rainbow'". Los Angeles Times. p. D12.

- ^ A.H. WEILER (Sep 28, 1966). "WARNERS TO CAST FOR A POT OF GOLD: 'Finian's Rainbow' Film with Fred Astaire Is Announced". New York Times. p. 41.

- ^ Martin, Betty (Feb 13, 1967). "Coppola to Direct 'Rainbow'". Los Angeles Times. p. c23.

- ^ Martin, Betty (Apr 3, 1967). "Steele in 'Finian's Rainbow'". Los Angeles Times. p. c30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Finian's Rainbow Original Soundtrack CD liner notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Finian's Rainbow at PetulaClark.net". Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ DVDJournal.com

- ^ "The Telegraph entry". Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ "'Finian's Rainbow' Set For Warner Penthouse; Landon: 'It's a La Mode'". Variety. May 15, 1968. p. 13.

- ^ York Times review

- ^ Chicago Sun-Times review

- ^ "Time Out review". Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1969", Variety, 7 January 1970 p 15

- ^ "Finian's Rainbow, Box Office Information". Worldwide Box Office. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ "'No Country for Old Men': The Coen Brothers and Cormac McCarthy's Ruthless Examination of Life • Cinephilia & Beyond". Cinephilia & Beyond. 2018-08-16. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- ^ "The 41st Academy Awards (1969) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- ^ Blu-Ray.com review

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Finian's Rainbow (1968 film) |

- 1968 films

- English-language films

- 1968 musical comedy films

- American films

- American musical comedy films

- Irish films

- Leprechaun films

- 1960s musical fantasy films

- Films based on musicals

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films scored by Ray Heindorf

- Warner Bros. films

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films about racism

- American musical fantasy films

- Napa Valley