The Godfather Part II

| The Godfather Part II | |

|---|---|

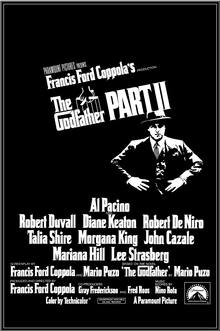

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Godfather by Mario Puzo |

| Produced by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Nino Rota |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 200 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $13 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $48–88 million[N 1] |

The Godfather Part II is a 1974 American epic crime film produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola from the screenplay co-written with Mario Puzo, starring Al Pacino, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, Robert De Niro, Talia Shire, Morgana King, John Cazale, Mariana Hill, and Lee Strasberg. It is the second installment in The Godfather trilogy. Partially based on Puzo's 1969 novel The Godfather, the film is both a sequel and a prequel to The Godfather, presenting parallel dramas: one picks up the 1958 story of Michael Corleone (Pacino), the new Don of the Corleone family, protecting the family business in the aftermath of an attempt on his life; the prequel covers the journey of his father, Vito Corleone (De Niro), from his Sicilian childhood to the founding of his family enterprise in New York City.

Following the success of the first film, Paramount Pictures began developing a follow-up to the film, with much of the same cast and crew returning. Coppola, who was given more creative control over the film, had wanted to make both a sequel and a prequel to the film that would tell the story of the rise of Vito and the fall of Michael. Principal photography began in October 1973 and wrapped up in June 1974. The Godfather Part II premiered in New York City on December 12, 1974, and was released in the United States on December 20, 1974, receiving divided reviews from critics but its reputation, however, improved rapidly and it soon became the subject of critical re-evaluation. It grossed between $48–88 million worldwide on a $13 million budget. The film was nominated for eleven Academy Awards at the 47th Academy Awards and became the first sequel to win for Best Picture. Its six Oscar wins also included Best Director for Coppola, Best Supporting Actor for De Niro and Best Adapted Screenplay for Coppola and Puzo. Pacino won the BAFTA Award for Best Actor and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Some have deemed it superior to The Godfather.[4] Like its predecessor, Part II remains a highly influential film, especially in the gangster genre, and is considered to be one of the greatest films of all time. In 1997, the American Film Institute ranked it as the 32nd-greatest film in American film history and it retained this position 10 years later.[5] It was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1993, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6] The Godfather Part III, the final installment in the trilogy, was released in 1990.

Plot[]

The film intercuts between events some time after The Godfather and the early life of Vito Corleone.

Vito[]

In 1901, the parents and brother of nine-year-old Vito Andolini are killed in Corleone, Sicily, after his father insults local Mafia chieftain Don Ciccio. Vito escapes on a ship to New York City, and is registered as "Vito Corleone" on Ellis Island. In 1917, having settled in New York, he marries and has a son, whom he names Santino ("Sonny"), with his wife. He loses his job in a grocery store due to the interference of Don Fanucci; his neighbor Clemenza invites Vito to take part in a burglary.

Vito has two more sons, Fredo and Michael. His criminal conduct attracts the attention of Fanucci, who extorts him. Vito's partners, Clemenza and Tessio, agree to pay him, but Vito insists Fanucci will accept a smaller payment if they make him "an offer he don't refuse". During a neighborhood festa, he stalks Fanucci to his apartment and shoots him dead. Vito becomes a respected and successful member of the community and is approached for help by a widow who is being evicted. After the widow's landlord learns of Vito's reputation, he agrees to let the widow stay on very favorable terms.

Vito and his family visit Sicily for the first time since his emigration. His business partner, Tommasino, accompanies him to Don Ciccio, ostensibly to ask for Ciccio's blessing on their olive oil business but Vito slices open Ciccio's chest with a knife after revealing his former identity.

In 1941, when the Corleones gather in their dining room to surprise Vito on his birthday, Michael announces that in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor, he has left college and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, leaving Sonny furious, Tom incredulous, and Fredo the only supportive brother. When Vito is heard at the door, all but Michael leave the room to greet him.

Michael[]

In 1958, during his son's First Communion party at Lake Tahoe, Michael has a series of meetings in his role as the don of the Corleone crime family. Frank Pentangeli, a Corleone capo, is dismayed that Michael refuses to help defend his territory against the Rosato brothers, who work for Hyman Roth, a Jewish Mob boss and long-standing Corleone business partner. That night, Michael leaves Nevada after surviving an assassination attempt at his home.

Michael suspects Roth planned the assassination, but feigns ignorance when they meet. In New York City, Pentangeli attempts to maintain Michael's pretense by making peace with the Rosatos, but they try to kill him. Roth, Michael, and several of their partners travel to Havana to discuss their future Cuban business prospects under the cooperative government of Fulgencio Batista. Michael becomes reluctant to continue operating in Cuba after reconsidering the viability of the ongoing Cuban Revolution. On New Year's Eve, Fredo inadvertently reveals that he knows Roth's right-hand man, Johnny Ola, having previously claimed that they had never met, and Michael realizes that it was Fredo who betrayed his location to Roth. Michael orders his bodyguard to kill Ola and Roth, but the assassin is shot dead by Cuban soldiers as he attempts to smother Roth with a pillow in his bed. Batista abdicates due to rebel advances. During the ensuing chaos, Michael, Fredo, and Roth separately escape to the United States. Back home, Michael learns that his wife Kay has miscarried.

In Washington, D.C., a Senate committee on organized crime is investigating the Corleone family. Pentangeli agrees to testify against Michael, who he believes had double-crossed him, and is placed under witness protection. On returning to Nevada, Fredo tells Michael that he felt resentful for being disregarded, first by Sonny and now by him. He claims to be ignorant of the plot on Michael's life and informs Michael that a lawyer advising the committee is on Roth's payroll. Michael disowns Fredo but gives orders that he is not to be harmed while their mother is still alive. Michael sends for Pentangeli's brother from Sicily as a hostage, resulting in Pentangeli renouncing his previous statement about Michael's role in the family; the hearing dissolves in an uproar. Kay reveals to Michael that she actually had an abortion, not a miscarriage, and that she intends to remove their children from Michael's criminal life. Outraged, Michael strikes Kay, banishes her from the family, and takes sole custody of the children.

Michael's mother Carmela dies, and Michael moves to wrap up loose ends. Roth is forced to return to the United States after being refused asylum and entry to Israel. Michael orders another capo, Rocco Lampone, to assassinate Roth; Lampone guns down Roth at Miami International Airport before being killed by return fire from federal agents. At Pentangeli's compound, consigliere Tom Hagen arrives and reminds the disgraced capo that failed plotters against the Roman emperor often committed suicide in return for clemency for their families, and assures him that his family will be cared for. Pentangeli then slits his wrists in his bathtub. Corleone enforcer Al Neri, acting on Michael's orders, shoots Fredo in the back of the head while the two men are fishing on the lake. Michael sits alone at the family compound.

Cast[]

- Al Pacino as Michael

- Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen

- Diane Keaton as Kay

- Robert De Niro as Vito Corleone

- John Cazale as Fredo Corleone

- Talia Shire as Connie Corleone

- Lee Strasberg as Hyman Roth

- Michael V. Gazzo as Frank Pentangeli

- G. D. Spradlin as Senator Pat Geary

- Richard Bright as Al Neri

- Gastone Moschin as Fanucci

- Tom Rosqui as Rocco Lampone

- B. Kirby Jr. as young Clemenza

- Frank Sivero as Genco

- Francesca De Sapio as young Mama Corleone

- Morgana King as Mama Corleone

- Mariana Hill as Deanna Corleone

- Leopoldo Trieste as Signor Roberto

- Dominic Chianese as Johnny Ola

- Amerigo Tot as Michael's bodyguard

- Troy Donahue as Merle Johnson

- John Aprea as young Tessio

- Joe Spinell as Willi Cicci

- Abe Vigoda as Tessio

- Harry Dean Stanton as F.B.I. agent

- Danny Aiello as Tony Rosato

Production[]

Development[]

Puzo started writing a script for a sequel in December 1971, before The Godfather was even released; its initial title was The Death of Michael Corleone.[7] Coppola's idea for the sequel would be to "juxtapose the ascension of the family under Vito Corleone with the decline of the family under his son Michael... I had always wanted to write a screenplay that told the story of a father and a son at the same age. They were both in their thirties and I would integrate the two stories... In order not to merely make Godfather I over again, I gave Godfather II this double structure by extending the story in both the past and in the present."[8]

Coppola, in his director's commentary on The Godfather Part II, mentioned that the scenes depicting the Senate committee interrogation of Michael Corleone and Frank Pentangeli are based on the Joseph Valachi federal hearings and that Pentangeli is like a Valachi figure.[9]

The film's original budget was $6 million but costs increased to over $11 million, with Variety's review claiming it was over $15 million.[10]

Casting[]

Coppola offered James Cagney a part in the film, but he refused.[11] James Caan agreed to reprise the role of Sonny in the birthday flashback sequence, demanding he be paid the same amount he received for the entire previous film for the single scene in Part II, which he received.[citation needed]

Several actors from the first film did not return for the sequel. Marlon Brando initially agreed to return for the birthday flashback sequence, but the actor, feeling mistreated by the board at Paramount, failed to show up for the single day's shooting.[citation needed] Coppola then rewrote the scene that same day.[citation needed] Richard S. Castellano, who portrayed Peter Clemenza in the first film, also declined to return, as he and the producers could not reach an agreement on his demands that he be allowed to write the character's dialogue in the film,[12] though this claim was disputed by Castellano's widow in a 1991 letter to People magazine.[13] The part in the plot originally intended for the latter-day Clemenza was then filled by the character of Frank Pentangeli, played by Michael V. Gazzo.[14]

Troy Donahue, in a small role as Connie's boyfriend, plays a character named Merle Johnson, which was his birth name.

Two actors who appear in the film played different character roles in other Godfather films: Carmine Caridi, who plays Carmine Rosato, also went on to play crime boss Albert Volpe in The Godfather Part III; Frank Sivero, who plays a young Genco Abbandando, appears as a bystander in The Godfather scene in which Sonny beats up Carlo for abusing Connie.[citation needed]

Among the actors depicting Senators in the hearing committee are film producer/director Roger Corman, writer/producer William Bowers, producer Phil Feldman, and actor Peter Donat.[15]

Filming[]

The Godfather Part II was shot between October 1, 1973 and June 19, 1974. The scenes that took place in Cuba were shot in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.[16] Charles Bluhdorn, whose Gulf+Western conglomerate owned Paramount, felt strongly about developing the Dominican Republic as a movie-making site. Forza d'Agrò was the Sicilian town featured in the film.[17]

Unlike with the first film, Coppola was given near-complete control over production. In his commentary, he said this resulted in a shoot that ran very smoothly despite multiple locations and two narratives running parallel within one film.[18]

Production nearly ended before it began when Pacino's lawyers told Coppola that he had grave misgivings with the script and was not coming. Coppola spent an entire night rewriting it before giving it to Pacino for his review. Pacino approved it and the production went forward.[18]

Coppola discusses his decision to make this the first major U.S. motion picture to use "Part II" in its title in the director's commentary on the DVD edition of the film released in 2002. Paramount was initially opposed because they believed the audience would not be interested in an addition to a story they had already seen. But the director prevailed, and the film's success began the common practice of numbered sequels.

Only three weeks prior to the release, film critics and journalists pronounced Part II a disaster. The cross-cutting between Vito and Michael's parallel stories were judged too frequent, not allowing enough time to leave a lasting impression on the audience. Coppola and the editors returned to the cutting room to change the film's narrative structure, but could not complete the work in time, leaving the final scenes poorly timed at the opening.[19]

It was the last major American motion picture to have release prints made with Technicolor's dye imbibition process until the late 1990s.

Music[]

Release[]

Theatrical[]

The Godfather Part II premiered in New York City on December 12, 1974, and was released in the United States on December 20, 1974.

Home media[]

Coppola created The Godfather Saga expressly for American television in a 1975 release that combined The Godfather and The Godfather Part II with unused footage from those two films in a chronological telling that toned down the violent, sexual, and profane material for its NBC debut on November 18, 1977. In 1981, Paramount released the Godfather Epic boxed set, which also told the story of the first two films in chronological order, again with additional scenes, but not redacted for broadcast sensibilities. Coppola returned to the film again in 1992 when he updated that release with footage from The Godfather Part III and more unreleased material. This home viewing release, under the title The Godfather Trilogy 1901–1980, had a total run time of 583 minutes (9 hours, 43 minutes), not including the set's bonus documentary by Jeff Werner on the making of the films, "The Godfather Family: A Look Inside".

The Godfather DVD Collection was released on October 9, 2001 in a package[20] that contained all three films—each with a commentary track by Coppola—and a bonus disc that featured a 73-minute documentary from 1991 entitled The Godfather Family: A Look Inside and other miscellany about the film: the additional scenes originally contained in The Godfather Saga; Francis Coppola's Notebook (a look inside a notebook the director kept with him at all times during the production of the film); rehearsal footage; a promotional featurette from 1971; and video segments on Gordon Willis's cinematography, Nino Rota's and Carmine Coppola's music, the director, the locations and Mario Puzo's screenplays. The DVD also held a Corleone family tree, a "Godfather" timeline, and footage of the Academy Award acceptance speeches.[21]

The restoration was confirmed by Francis Ford Coppola during a question-and-answer session for The Godfather Part III, when he said that he had just seen the new transfer and it was "terrific".

The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration[]

After a careful restoration of the first two movies, The Godfather movies were released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc on September 23, 2008, under the title The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration. The work was done by Robert A. Harris of Film Preserve. The Blu-ray Disc box set (four discs) includes high-definition extra features on the restoration and film. They are included on Disc 5 of the DVD box set (five discs).

Other extras are ported over from Paramount's 2001 DVD release. There are slight differences between the repurposed extras on the DVD and Blu-ray Disc sets, with the HD box having more content.[22]

Video game[]

A video game based on the film was released for Windows, PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in April 2009 by Electronic Arts. It received negative reviews and sold poorly, leading Electronic Arts to cancel plans for a game based on The Godfather Part III.[23]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The Godfather Part II did not surpass the original film commercially, but in the United States and Canada it grossed $47.5 million.[2] It was Paramount Pictures' highest-grossing film of 1974 and was the seventh-highest-grossing picture in the United States that year. Re-released twice more since its original release, the film grossed between $48–88 million worldwide.[N 1]

Critical response[]

Initial critical reception of The Godfather Part II was divided,[27] with some dismissing the work and others declaring it superior to the first film.[28][29] While its cinematography and acting were immediately acclaimed, many criticized it as overly slow-paced and convoluted.[30] Vincent Canby viewed the film as "stitched together from leftover parts. It talks. It moves in fits and starts but it has no mind of its own. [...] The plot defies any rational synopsis."[14] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic accused the story of featuring "gaps and distentions."[31] A mildly positive Roger Ebert awarded three stars out of four[32] and wrote that the flashbacks "give Coppola the greatest difficulty in maintaining his pace and narrative force. The story of Michael, told chronologically and without the other material, would have had really substantial impact, but Coppola prevents our complete involvement by breaking the tension." Though praising Pacino's performance and lauding Coppola as "a master of mood, atmosphere, and period", Ebert considered the chronological shifts of its narrative "a structural weakness from which the film never recovers".[30] Gene Siskel gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, writing that it was at times "as beautiful, as harrowing, and as exciting as the original. In fact, 'The Godfather, Part II' may be the second best gangster movie ever made. But it's not the same. Sequels can never be the same. It's like being forced to go to a funeral the second time—the tears just don't flow as easily."[33]

The film quickly became the subject of a critical re-evaluation.[34] Whether considered separately or with its predecessor as one work, The Godfather Part II is now widely regarded as one of the greatest films in world cinema. Many critics compare it favorably with the original – although it is rarely ranked higher on lists of "greatest" films. Roger Ebert retrospectively awarded it a full four stars in a second review and inducted the film into his Great Movies section, praising the work as "grippingly written, directed with confidence and artistry, photographed by Gordon Willis [...] in rich, warm tones."[35] Michael Sragow's conclusion in his 2002 essay, selected for the National Film Registry web site, is that "[a]lthough "The Godfather" and "The Godfather Part II" depict an American family's moral defeat, as a mammoth, pioneering work of art it remains a national creative triumph."[36] In his 2014 review of the film, Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian wrote "Francis Coppola's breathtakingly ambitious prequel-sequel to his first Godfather movie is as gripping as ever. It is even better than the first film, and has the greatest single final scene in Hollywood history, a real coup de cinéma."[37]

The Godfather Part II was featured on Sight & Sound's Director's list of the ten greatest films of all time in 1992 (ranked at No. 9)[38] and 2002 (where it was ranked at No. 2. The critics ranked it at No. 4)[39][40][41] On the 2012 list by the same magazine the film was ranked at No. 31 by critics and at No. 30 by directors.[42][43][44] In 2006, Writers Guild of America ranked the film's screenplay (Written by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppla) the 10th greatest ever.[45] It ranked No. 7 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the "100 Greatest Movies of All Time", and #1 on TV Guide's 1998 list of the "50 Greatest Movies of All Time on TV and Video".[46] The Village Voice ranked The Godfather Part II at No. 31 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[47] In January 2002, the film (along with The Godfather) was voted at No. 39 on the list of the "Top 100 Essential Films of All Time" by the National Society of Film Critics.[48][49] In 2017, it ranked No. 12 on Empire magazine's reader's poll of The 100 Greatest Movies.[50] In a earlier poll held by the same magazine in 2008, it was voted 19th on the list of 'The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time'.[51] On Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a 96% approval rating based on 113 reviews, with an average rating of 9.70/10. The consensus reads, "Drawing on strong performances by Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, Francis Ford Coppola's continuation of Mario Puzo's Mafia saga set new standards for sequels that have yet to be matched or broken."[52] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 90 out of 100 based on 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[53] In 2015, it was tenth in the BBC's list of the 100 greatest American films.[54]

Many believe Pacino's performance in The Godfather Part II is his finest acting work, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was criticized for awarding the Academy Award for Best Actor that year to Art Carney for his role in Harry and Tonto. It is now regarded as one of the greatest performances in film history. In 2006, Premiere issued its list of "The 100 Greatest Performances of all Time", putting Pacino's performance at #20.[55] Later in 2009, Total Film issued "The 150 Greatest Performances of All Time", ranking Pacino's performance fourth place.[56]

Accolades[]

This film is the first sequel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture.[57] The Godfather and The Godfather Part II remain the only original/sequel combination both to win Best Picture.[58] Along with The Lord of the Rings, The Godfather Trilogy shares the distinction that all of its installments were nominated for Best Picture; additionally, The Godfather Part II and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King are the only sequels to win Best Picture.

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 47th Academy Awards[57] | Best Picture | Francis Ford Coppola, Gray Frederickson and Fred Roos | Won |

| Best Director | Francis Ford Coppola | Won | |

| Best Actor | Al Pacino | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Robert De Niro | Won | |

| Michael V. Gazzo | Nominated | ||

| Lee Strasberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Talia Shire | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo | Won | |

| Best Art Direction | Dean Tavoularis, Angelo P. Graham and George R. Nelson | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Theadora Van Runkle | Nominated | |

| Best Original Dramatic Score | Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola | Won | |

| 29th British Academy Film Awards | Best Actor | Al Pacino (Also for Dog Day Afternoon) | Won |

| Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles | Robert De Niro | Nominated | |

| Best Film Music | Nino Rota | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Peter Zinner, Barry Malkin, and Richard Marks | Nominated | |

| 27th Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Francis Ford Coppola | Won |

| 32nd Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | Francis Ford Coppola | Nominated | |

| Best Motion Picture Actor – Drama | Al Pacino | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Newcomer – Male | Lee Strasberg | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Nino Rota | Nominated | |

| 27th Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Drama Adapted from Another Medium | Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo | Won |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Director | Francis Ford Coppla | Won |

American Film Institute recognition[]

- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #32[59]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Michael Corleone – #11 Villain[60]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #32[63]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 – #3 Gangster Film and Nominated Epic Film[64]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sources disagree on the amount grossed by the film. Releases:[24] Some sources claim an original release of $88 million.[25][26]

References[]

- ^ "The Godfather II". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Godfather Part II (1974)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ Stax (July 28, 2003). "Featured Filmmaker: Francis Ford Coppola". Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ "Citizen Kane Stands the Test of Time" Archived August 24, 2011, at WebCite. American Film Institute.

- ^ "The National Film Registry List – Library of Congress". loc.gov. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ "The Godfather". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on March 31, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Gene (2004). Godfather: The Intimate Francis Ford Coppola. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2304-2.

- ^ "Director commentary". The Godfather Part II. 1974. ASIN B00003CXAA.

- ^ The Godfather Part II at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ Cagney, James (1976). Cagney by Cagney. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-671-80889-1. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Lumenick, Lou (March 15, 2012). "Leave the gun-Take my career". The New York Post. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ Sheridan-Castellano, Ardell (2003). Divine Intervention and a Dash of Magic... Unraveling The Mystery of "The Method" + Behind the Scenes of the original Godfather film. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-55369-866-5.[self-published source]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Canby, Vincent (December 13, 1974). "'Godfather, Part II' Is Hard To Define: The Cast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum. p. 711. ISBN 9780826429773.

- ^ "Movie Set Hotel: The Godfather II Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", HotelChatter, May 12, 2006.

- ^ "In search of... The Godfather in Sicily". The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media Limited. April 26, 2003. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Godfather Part II DVD commentary featuring Francis Ford Coppola, [2005]

- ^ The Godfather Family: A look Inside

- ^ "DVD review: 'The Godfather Collection'". DVD Spin Doctor. July 2007.

- ^ The Godfather DVD Collection [2001]

- ^ "Godfather: Coppola Restoration", September 23 Archived January 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on DVD Spin Doctor

- ^ "EA buries Godfather franchise". GameSpot. June 9, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

Original release: $47,643,435; 2010 re-release: $85,768; 2019 re-release: $291,754

- ^ Thompson, Anne (December 24, 1990). "Is 'Godfather III' an offer audiences cannot refuse?". Variety. p. 57.

- ^ "'The Godfather Part II' At 45 And Why It Remains The Gold Standard For Sequels". forbes.com. November 9, 2019. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel (2009). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 712. ISBN 978-1-4411-1647-5.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (1991). The Godfather Companion. Wildside Press. ISBN 0-8095-9036-0.

- ^ "The Godfather, Part II". Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The 'Godfather Part II' Sequel Syndrome". Newsweek. December 25, 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

But when the movie arrived in theaters at the end of 1974, it was met with a critical reception that, compared with today's exuberant embrace, felt more like a slap in the face. [...] Most professional tastemakers, even those exasperated by what they felt was the movie's sometimes plodding-pace, recognized the creative crowning achievements of the film's direction, cinematography and acting.

- ^ Berliner, Todd (2010). Hollywood Incoherent: Narration in Seventies Cinema. University of Texas Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-292-72279-8. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Godfather, Part II". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 20, 1974). "'The Godfather, Part II': Father knew best". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 1.

- ^ Garner, Joe (2013). Now Showing: Unforgettable Moments from the Movies. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4494-5009-0. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 2, 2008). "The Godfather, Part II Movie Review (1974)". Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (2002). "The Godfather and The Godfather Part II" (PDF). "The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films," 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 20, 2014). "The Godfather: Part II - review". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 1992". thependragonsociety.

- ^ "Sight & Sound 2002 Directors' Greatest Films poll". listal.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – The Critics' Top Ten Films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – The Directors' Top Ten Films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Directors' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Critics' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound. BFI. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "TV Guide's 50 Greatest Movies On TV/Video". thependragon.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ Carr, Jay (2002). The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films. Da Capo Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-306-81096-1. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ "100 Essential Films by The National Society of Film Critics". filmsite.org.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies". Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Green, Willow (October 3, 2008). "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire.

- ^ "The Godfather, Part II". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest American Films". bbc. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Performances" Archived August 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine filmsite.org

- ^ "The 150 Greatest Performances Of All Time" Archived January 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine TotalFilm. com

- ^ Jump up to: a b "47th Academy Awards Winners: Best Picture". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ McNamara, Mary (December 2, 2010). "Critic's Notebook: Can 'Harry Potter' ever capture Oscar magic?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Gangster". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Godfather Part II |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Godfather Part II. |

- The Godfather Part II at IMDb

- The Godfather Part II at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Godfather Part II at Box Office Mojo

- The Godfather Part II at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Godfather Part II at Metacritic

- The Godfather Part II essay by Michael Sragow on the National Film Registry website [1]

- 1974 films

- 1974 crime films

- American crime films

- American epic films

- American films

- American sequel films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- English-language films

- Father and son films

- Films about the American Mafia

- Films about the Sicilian Mafia

- Films based on American crime novels

- Films based on organized crime novels

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films produced by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films scored by Nino Rota

- Films set in 1901

- Films set in 1917

- Films set in 1941

- Films set in 1958

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in Havana

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Sicily

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films shot in Miami

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films with screenplays by Mario Puzo

- Fratricide in fiction

- The Godfather films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Sicilian-language films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Cultural depictions of the Mafia

- Films about the Cuban Revolution