Camelot (film)

| Camelot | |

|---|---|

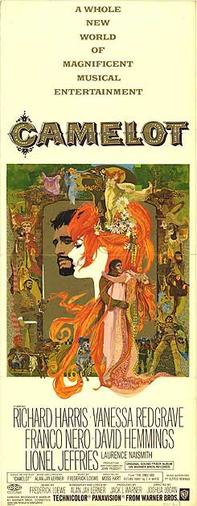

Theatrical release poster by Bob Peak | |

| Directed by | Joshua Logan |

| Screenplay by | Alan Jay Lerner |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | Jack L. Warner |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Richard H. Kline |

| Edited by | Folmar Blangsted |

| Music by | Frederick Loewe Alfred Newman[1] |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts |

Release date |

|

Running time | 180 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13 million |

| Box office | $31.5 mllion[2] |

Camelot is a 1967 American musical fantasy comedy drama film directed by Joshua Logan and written by Alan Jay Lerner, based on the 1960 stage musical of the same name by Lerner and Frederick Loewe. It stars Richard Harris as King Arthur, Vanessa Redgrave as Guenevere, and Franco Nero as Lancelot. The cast also features David Hemmings, Lionel Jeffries, and Laurence Naismith.

In April 1961, the rights to produce a film adaptation of Camelot were obtained by Warner Bros. with Lerner attached to write the screenplay. However, the film was temporarily shelved as the studio decided to adapt My Fair Lady into a feature film first. In 1966, development resumed with the hiring of Logan as director. Original cast members Richard Burton and Julie Andrews were approached to reprise their roles from the stage musical, but both declined and were replaced with Harris and Redgrave. Filming took place on location in Spain and on the Warner Bros. studio lot in Burbank, California.

The film was released on October 25, 1967 to mixed to negative reviews from film critics but was a commercial success, grossing $31.5 million on a $13 million budget, becoming the tenth highest grossing film of 1967. The film received five nominations at the 40th Academy Awards and won three; Best Score, Best Production Design, and Best Costume Design. It also won three Golden Globe Awards; Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy (Richard Harris), Best Original Song (for "If Ever I Would Leave You"), and Best Original Score.

Plot[]

King Arthur is preparing for a great battle against his friend, Sir Lancelot, a battle he does not wish to fight but has been forced into. Arthur reflects on the sad circumstances which have led him to this situation and asks his childhood mentor, Merlyn, for advice. Merlyn appears to him and tells Arthur to think back.

Arthur thinks back to the night of his marriage to his now-estranged wife, Guenevere. It is an arranged marriage, and he has never met her before. He is understandably afraid of what lies ahead ("I Wonder What the King is Doing Tonight"). His solitude is broken by Guenevere, who has fled from her entourage and enters the same woods that he has taken refuge in. Guenevere is also worried about marrying a man she has never met, and longs for the romantic life of a fought-over maiden ("The Simple Joys of Maidenhood"). Overhearing Guenevere and realizing who she is, Arthur accidentally falls out of the tree in which he is hiding. He and Guenevere converse, and as she does not know his true identity, she fantasizes about traveling with him and escaping before his "wretched king" finds her. Arthur tells her what a wonderful place his kingdom is ("Camelot"). She finds herself drawn to him, but they are interrupted by his men and her entourage. Arthur's identity is revealed, and Guenevere gladly goes with him to be married.

The plot shifts to four years later. Arthur dreams up and explores with Guenevere his idea for a "Round Table" that would seat all the noble knights of the realm, reflecting not only a crude type of democratic ideal, but also the political unification of England. Knights are shown gathering from all over England. Eventually, word of Arthur's Round Table spreads to France. Inspired by Arthur's ideas, the French Knight Lancelot makes his way to England with his squire Dap, boasting of his superior virtues ("C'est Moi"). Lancelot's prowess impresses Arthur, and they become friends; however, many of the knights instantly despise Lancelot for his self-righteousness and boasting manner. Back in Camelot, Guinevere and the women frolic and gather flowers to celebrate the coming of spring (“The Lusty Month of May”).

Guenevere, who initially dislikes Lancelot, incites three of the best knights – Sir Lionel, Sir Sagramore, and Sir Dinadan – to challenge him to a joust ("Then You May Take Me To The Fair"). Arthur ponders this discord and how distant Guenevere has become recently ("How to Handle a Woman"). However, Guenevere's plan goes awry as Lancelot easily defeats all three, critically wounding Sir Dinadan. A horrified Lancelot pleads for Sir Dinadan to live, and as he lays hands on him, Dinadan miraculously recovers. Guenevere is so overwhelmed and humbled that her feelings for Lancelot begin to change. Despite his vows of celibacy, Lancelot falls in love with Guenevere, leading to the famous love triangle involving Arthur, Guenevere, and Lancelot. The other knights are aware of the clandestine meetings between Lancelot and Guenevere. They accuse Lancelot repeatedly, and several knights are banished after losing their armed challenges.

Guinevere and Lancelot meet in secret to discuss the latest accusation, the knights' banishment, and their future. Guenevere does not believe Arthur knows yet, but Lancelot tells her that he does, which causes her much guilt and anguish. Lancelot vows that he should leave and never come back, but finds it impossible to consider leaving Guenevere ("If Ever I Would Leave You").

Arthur knows something is going on between Lancelot and Guenevere, but he cannot bring himself to accuse them because he loves them both. He decides to rise above the scandal and ignore it. However, Mordred, Arthur's illegitimate son from an affair with the Princess Morgause before he was crowned, arrives at Camelot bitter because Arthur will not recognize him as son and heir. Mordred is determined to bring down the fellowship of the Round Table by stirring up trouble. All this takes its toll on Arthur's disposition, and Guenevere tries to cheer him up ("What Do the Simple Folk Do?") despite her conflicted emotions.

Mordred cunningly convinces Arthur to stay out hunting all night as a test, knowing that Lancelot will visit Guenevere in her bedchamber. Everything happens as Mordred expected, except that Lancelot and Guenevere had intended to make this visit the last time they will see each other. They sing of their forbidden love and how wrong it has all gone ("I Loved You Once In Silence"). But Mordred and several knights are waiting behind the curtains, and they catch the lovers together. Lancelot escapes, but Guenevere is arrested and sentenced to die by burning at the stake, thanks to Arthur's new civil court and trial by jury. Arthur, who has promoted the rule of law throughout the story, is now bound by his own law and cannot spare Guenevere. "Kill the Queen or kill the law," says Mordred. Preparations are made for Guenevere's burning ("Guenevere"), but Lancelot rescues her at the last minute, much to Arthur's relief. However, many knights are killed, and the knights demand vengeance.

The plot returns to the opening. Arthur is preparing for battle against Lancelot, at the insistence of his knights who want revenge, and England appears headed back into the Dark Ages. Arthur receives a surprise visit from Lancelot and Guenevere, at the edge of the woods, where she has taken residence at a convent. Lancelot asks if there is nothing to be done, but Arthur can think of nothing but to let the events ride out. They clasp arms in farewell, and Lancelot leaves. Arthur and Guenevere share an emotional farewell, his heart breaking when he sees that she has had all her glorious hair chopped off. She is beside herself that she may never see him again or know his forgiveness.

Prior to the battle, Arthur stumbles across a young boy named Tom, who wishes to fight in the battle and become a Knight of the Round Table. Tom espouses his commitment to Arthur's original ideal of "Not might 'makes' right, but might 'for' right." Arthur realizes that, although most of his plans have fallen through, the ideals of Camelot still live on in this simple boy. Arthur knights Tom and gives him his orders—run behind the lines and survive the battle, so that he can tell future generations about the legend of Camelot. Watching Tom leave, Arthur regains his hope for the future ("Camelot (reprise)").

Comparison to source material[]

Several songs were omitted from the film version: "The Jousts", a choral episode in which the jousts, which occur offstage in the play, are described (in the film they are shown); "Before I Gaze At You Again", sung by Guenevere to an offstage Lancelot; "The Seven Deadly Virtues", sung by Mordred; "Persuasion", sung in a scene not in the film, in which Mordred persuades Morgan Le Fay, who is omitted from the film's screenplay, to conjure up an enchantment to keep Arthur in the forest so that Guenevere and Lancelot's affair can be exposed; and "Fie On Goodness!", sung by the knights, in which they bemoan the fact that they are no longer allowed to administer punishment no matter how inappropriate, but according to the law. Some songs were cut during the original Broadway run of Camelot, because they made the play too long. However, they were restored for the London production starring Laurence Harvey and Elizabeth Larner.

In both the stage and film version, Merlin has disappeared from Arthur's life as an adult. However, in the play, this occurs immediately after the meeting of Arthur and Guinevere, as a result of the water nymph Nimue putting an enchantment on Merlyn to entice him to live with her in her cave. In the film, this is assumed to have occurred long before the meeting with Guinevere, and Merlin is excised from this scene. In the stage version, when Nimue is seducing Merlin, she sings "Follow Me". In the film, this song has been completely rewritten and is sung by an offscreen children's chorus in a scene roughly three-fourths into the show in which Arthur goes to a special place in the forest to consult Merlin. (This scene was added to later versions of the stage musical but these kept "Follow Me" in its original place.) The new lyrics suggest Merlin is living in a kind of paradise, but do not imply he has been lured there. Nimue does not appear in the film.

Although popular recordings of "Follow Me" usually use the lyrics from the original stage musical, Frank Sinatra's recording uses the revised lyrics from the film.

Production[]

Development[]

In April 1961, it was reported that Warner Bros. had purchased the rights to produce a film adaptation of the stage musical with Alan Jay Lerner hired to pen the screenplay.[3][4] That same month, it was reported that Rock Hudson had signed on to portray King Arthur.[5] In May 1961, Shirley Jones was reportedly in talks to portray Guenevere.[6] However, development was placed on hold when Warner fast-tracked to produce a film adaptation of My Fair Lady in which they purchased the film rights for $5.5 million. It was also stipulated that the film would not be released before April 1964.[7] Nevertheless, in April 1963, Jack L. Warner had hired former television producer William T. Orr to serve as producer. It was also reported that he sought original cast members Richard Burton and Robert Goulet to star in their respective roles along with Elizabeth Taylor to star as Guenevere.[8][9]

Robert Wise was offered the opportunity to direct, but production chief Walter MacEwen noted that "He does not want to type himself as a director of musical subjects—and he still has The Gertrude Lawrence Story, which falls in that category, on his slate for next year."[10] Instead, in March 1966, it was reported that Joshua Logan was hired to direct with principal photography slated to commence in August.[11]

Casting[]

| Actor | Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Richard Harris | King Arthur | |

| Vanessa Redgrave | Guinevere | |

| Franco Nero | Lancelot du Lac | |

| David Hemmings | Mordred | |

| Lionel Jeffries | King Pellinore | |

| Laurence Naismith | Merlin | |

| Pierre Olaf | Dap | |

| Estelle Winwood | Lady Clarinda | |

| Gary Marshal | Sir Lionel | |

| Anthony Rogers | Sir Dinadan | |

| Peter Bromilow | Sir Sagramore | |

| Sue Casey | Lady Sibyl | |

| Gary Marsh | Tom of Warwick | |

| Nicolas Beauvy | Young Arthur | |

| Gene Merlino | Lancelot's singing voice |

Warner approached Burton to reprise his stage role as Arthur, but he demanded a higher salary than the studio was willing to pay, in which the negotiations ceased. In his place, Peter O'Toole, Gregory Peck and Marlon Brando were considered. While filming Hawaii (1966), Richard Harris learned of Camelot and actively sought for the role.[10] For four months, Harris sent complimentary letters, cables and offers for a screen test to Lerner, Logan and Jack Warner indicating his interest in the role. Logan refused his offer due to his lack of singing abilities. When Logan returned to The Dorchester after having his morning jog, Harris ambushed him again about the role in which Logan finally relented as he offered to pay for his own screen test. Harris later hired cinematographer Nicolas Roeg to direct his screen test, which impressed Logan and Warner, who both agreed to hire him.[12][13]

For the role of Guenevere, Julie Andrews, Audrey Hepburn and Julie Christie were on the studio's shortlist while Jack Warner separately considered Polly Bergen, Ann-Margret and Mitzi Gaynor.[14] Andrews had learned of the movie adaptation while filming Hawaii, but she declined.[15] However, Logan desperately wanted to cast Vanessa Redgrave after seeing her performance in Morgan – A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966). However, he had to wait several months as Redgrave was performing in the stage play The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Despite her not being a traditional singer, Logan was impressed by her renditions of folk songs that he listened to. The studio was initially reluctant due to her left-wing activism, but Logan negotiated for her casting until after she fulfilled her stage commitments. Redgrave was signed in November 1966 for $200,000 and permitted to do her own singing.[16]

Although the studio initially sought a Frenchman, Italian actor Franco Nero was cast as Lancelot based on the recommendation from Harris and John Huston who worked with Nero on The Bible: In the Beginning... (1966). Although Logan was aware of Nero's thick Italian accent, he initially permitted him to do his own singing.[17] The first scene shot was his performance of the musical number "C'est Moi", by which Logan found Nero's singing voice incompatible with the song's musical arrangement. His singing voice was dubbed by Gene Merlino while Nero was given a speech coach to help improve his English.[18]

Filming[]

Richard H. Kline came to attention of Logan after he watched the footage from Chamber of Horrors (1966), which contained medieval castle doors with a carriage drawn by a team of gray horses rolling through a bricked courtyard that had been shot with muted colors of the woods and mist. Impressed, Logan hired Kline as cinematographer. For Camelot, Kline wanted to shoot the film in a more authentically textured style rather than the polished look of Hollywood musicals.[19]

As his first film credit, 29-year-old Australian set designer John Truscott, who created the sets for the London and Melbourne stage productions of Camelot, was hired as production designer. According to Logan, Truscott envisioned the visual design that resembled "neither Gothic or Romanesque but an in between period, suggesting a legendary time".[20] The Castillo de Coca was the inspiration for the film's production design, which was re-created on the studio backlot in Burbank, California. The finished castle became the largest set ever constructed at the time, measuring 400 by 300 feet, and nearly 100 feet with the reported cost covered roughly $500,000. Logan later explained that "it was absolutely necessary since we expect to do everything right in this picture—even to matching Spanish and Hollywood cobblestones."[21][22]

In September 1966, shooting commenced on location in Spain intended for a 30-day shooting schedule. For the exterior sets, Logan selected seven castles on the country's mainland and another one on the island of Majorca,[23] of which included the Alcázar of Segovia that was used as Lancelot de Luc's castle and the Medina del Campo. However, the location shoot experienced setbacks due to the country's rainfall and high temperature in which filming finished twelve days behind schedule. In total, the shoot yielded half an hour of usable footage.[24] With production underway, Jack Warner decided that Camelot would be his last film he would produce for the studio. On November 14, 1966, he sold a substantial share of studio stock to Seven Arts Productions. The sale was finalized on November 27, which yielded to approximately $32 million in cash.[25][26]

Following the location shoot in Spain, the filming unit took a seven-week hiatus.[citation needed] By then, fifteen of the studio's twenty-three stage sets were occupied for Camelot.[27] Filming was further complicated when Harris required 12 facial stitches after he fell down in his shower. Against the doctor's orders, the stitches reopened when Harris went out to party, which further delayed his recovery. Plastic surgery was later applied to disguise the wound.[28]

Music[]

On the soundtrack album, "Take Me to the Fair" appears after "How to Handle a Woman", and "Follow Me" (with new lyrics written for the film) is listed after "The Lusty Month of May".

- "Prelude/Overture" – Orchestra

- "Guinevere" – Arthur

- "I Wonder What the King is Doing Tonight" – Arthur

- "The Simple Joys of Maidenhood" – Guenevere

- "Camelot" – Arthur

- "Camelot" (Reprise) – Guenevere, Arthur and Chorus

- "C'est Moi" – Lancelot

- "The Lusty Month of May" – Guenevere and Women

- "Take Me to the Fair" – Guenevere, Lionel, Dinadan and Sagramore

- "How to Handle a Woman" – Arthur

- "Entr'acte"

- "If Ever I Would Leave You" – Lancelot

- "What Do the Simple Folk Do?: – Guenevere and Arthur

- "I Loved You Once in Silence" – Guenevere

- "Follow Me"/"Children's Chorus" – Chorus

- "Guenevere" – Chorus

- "Finale Ultimo" – Arthur and Tom

- "Exit Music"

Historical context[]

Vietnam[]

William Johnson noted that "some of Arthur's speeches could be applied directly to Vietnam," such as Arthur's "Might for Right" ideal and repeated musings over borderlines.[29] At the same time, Alice Grellner suggested the movie served as "an escape from the disillusionment of Vietnam, the bitterness and disenchantment of the antiwar demonstrations, and the grim reality of the war on the evening television news" and reminder of John F. Kennedy's presidency.[30]

Release[]

On October 25, 1967, Camelot premiered at the Warner Theatre on Broadway and 47th Street. A benefit premiere was held on November 1 at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles. While the official running time was 180 minutes plus overture, entr'acte and exit music, only the 70mm blow up prints and 35mm magnetic stereo prints contained that running time. For general wide release, the film was truncated to 150 minutes.[31] Cuts were made in scattered pieces of dialogue and entire stanzas from a number of songs including "C'est Moi" and "What Do the Simple Folk Do?". Omitted scenes include Arthur explaining what he means when he says that Merlin lives backwards, and the entire flashback of Arthur in the forest recalling Merlin's schoolhouse.[citation needed]

Television broadcasts and home video versions contain the complete, unedited cut. The shorter general release version has not been seen since the film's 1973 re-release.[citation needed]

Home media[]

In April 2012, the film was released on Blu-ray in conjunction with the film's 45th anniversary. The release was accompanied with an audio commentary, four behind-the-scenes featurettes and five theatrical trailers.[32]

Reception[]

Box office[]

Camelot was ranked as the tenth highest-grossing film of 1967 earning $12.3 million in United States and Canadian rentals.[33] During its 1973 re-release, the film grossed $2 million in North American rentals.[34]

Critical reaction[]

Film Quarterly's William Johnson called Camelot "Hollywood at its best and worst," praising the film's ideals and Harris and Redgrave's performances but bemoaning its lavish sets and three-hour-running time.[29] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Redgrave "dazzling" but criticized the film's conflicting moods and uncomfortable close-ups. Crowther felt the main characters were not sufficiently fleshed out to evoke any sympathy from the audience, concluding that the filmed lacked "magic".[35] Variety ran a positive review, declaring that the film "qualifies as one of Hollywood's alltime great screen musicals," praising the "clever screenplay" and "often exquisite sets and costumes."[36] Clifford Terry of the Chicago Tribune was also positive, calling it "a beautiful, enjoyable splash of optical opiate" with "colorful sets, bright costumes and three fine performances."[37]

Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post wrote, "Long, leaden and lugubrious, the Warner's 'Camelot' is 15 million dollars worth of wooden nickels. Besides being hopelessly, needlessly lavish, this misses the point squarely on the nail: what was so hot about King Arthur? We never really are told." He added that Richard Harris as Arthur gave "the worst major performance in years."[38] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called the film "a very considerable disappointment," writing that its moments of charm "simply cannot cancel out the slow static pace, the lack of style, the pinched and artificial quality of the proceedings, the jumpy and inconsistent cuts, the incessant overuse of close-ups, the failure to sustain emotional momentum, the fatal wavering between reality and fantasy, the inability to exploit the resources of the film medium."[39]

Brendan Gill of The New Yorker declared, "On Broadway, 'Camelot' was a vast, costly, and hollow musical comedy, and the movie version is, as might have been predicted, vaster, more costly, and even more hollow."[40] The Monthly Film Bulletin of the UK wrote, "A dull play has become an even duller film, with practically no attempt at translation into the other medium, and an almost total neglect of the imaginative possibilities of the splendid material embodied in the Arthurian legend. Why, for instance, is Arthur not shown extracting Excalibur from the rock instead of merely talking about it? Such is the stuff of film scenes."[41] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Camelot holds an approval rating of 41%, based on 17 reviews with an average rating of 6.23/10.[42]

Awards and nominations[]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[43] | Best Art Direction | John Truscott, Edward Carrere and John W. Brown | Won |

| Best Cinematography | Richard H. Kline | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | John Truscott | Won | |

| Best Original Song Score or Adaptation Score | Alfred Newman and Ken Darby | Won | |

| Best Sound | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts Studio Sound Department | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[44] | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Richard Harris | Won | |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Vanessa Redgrave | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score – Motion Picture | Frederick Loewe | Won | |

| Best Original Song – Motion Picture | "If Ever I Should Leave You" – Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe | Won | |

| Most Promising Newcomer – Male | Franco Nero | Nominated | |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actress | Vanessa Redgrave | Won[a] |

| Writers Guild of America Awards[45] | Best Written American Musical | Alan Jay Lerner | Nominated |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Camelot" – Nominated[46]

Legacy[]

Despite its high cost, Camelot was widely criticized for its cheap appearance because it had obviously been filmed on an architecturally ambiguous set amidst the chaparral-covered hills of Burbank, and not an authentic medieval castle amidst the green hills of England.[47] As a result, Camelot was the last American film that attempted to physically construct a large-scale full-size set on a studio backlot to represent an exotic foreign location.[47] To ensure authenticity, American filmmakers have resorted to location shooting ever since for exterior shots.[47]

A life-size statue of Richard Harris, as King Arthur from this film, has been erected in Bedford Row, in the centre of his home town of Limerick. The sculptor of this statue was the Irish sculptor Jim Connolly, a graduate of the Limerick School of Art and Design.[48]

See also[]

- List of American films of 1967

- List of films based on Arthurian legend

Notes[]

- ^ Tied with Lynn Redgrave for Georgy Girl.

References[]

- ^ "CAMELOT". United States Library of Congress.

- ^ "Camelot (1967)". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ "WB's 'Camelot' Buy: $1,500,000 plus 25% of Net". Variety. April 12, 1961. p. 1.

- ^ "Warner Buys Camelot Rights". San Pedro News-Pilot. April 12, 1961. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (April 28, 1961). "Rock Hudson Will Star in 'Camelot'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Connolly, Mike (May 25, 1961). "Shirley Jones Up for 'Camelot'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 26.

- ^ "Orr Does Warners' 'Camelot'". North Hollywood Valley Times. April 23, 1963. p. 4. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lyons, Leonard (April 29, 1963). "William Orr Seeks Burton, Taylor, Goulet For 'Camelot' Movie Leads". Tampa Bay Times. p. 14-D. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kennedy 2014, p. 27.

- ^ "Logan to Direct 'Camelot'". Los Angeles Times. March 10, 1966. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sellers, Richard (2008). The Life and Inebriated Times of Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Peter O'Toole, and Oliver Reed. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-312-55399-9.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 28.

- ^ Stirling, Richard (2009). Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 165–6. ISBN 978-0312564988.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 28–9.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 34.

- ^ C. Udel, James (2013). "Richard Kline, Cinematographer". The Film Crew of Hollywood: Profiles of Grips, Cinematographers, Designers, a Gaffer, a Stuntman and a Makeup Artist. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786464845.

- ^ Stubbs, Jonathan (2019). "Boom or Bust". Hollywood and the Invention of England: Projecting the English Past in American Cinema, 1930-2017. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-1501305856.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Alpert, Don (September 26, 1966). "Long Walk for a 'Camelot'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Spanish Castles in 'Camelot'". Star-Gazette. September 3, 1966. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 33–4.

- ^ "Warner Completes Sale of Film Stock". The New York Times. November 28, 1966. p. 65. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 84–5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson, William (1968). "Short Notices: Camelot". Film Quarterly. 21 (3): 56. doi:10.2307/1211006. JSTOR 1211006.

- ^ Davidson, Roberta (2007). "The 'Reel' Arthur: Politics and Truth Claims in 'Camelot, Excalibur, and King Arthur.'". Arthuriana. 17 (2): 62–84. doi:10.1353/art.2007.0037. JSTOR 27870837. S2CID 153367690.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 89.

- ^ Katz, Josh (January 9, 2012). "Camelot: 45th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "All-Time Box Office Champs". Variety. January 6, 1971. p. 12.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1974". Variety. January 8, 1975. p. 24.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 26, 1967). "Arrives at Warner: Film Hasn't Overcome Stage Play's Defects". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Camelot". Variety. October 25, 1967. p. 6.

- ^ Terry, Clifford (October 30, 1967) "'Camelot' Is Enjoyable Knight-Time Journey". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 16.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (November 9, 1967). "'Camelot' Tommyrot". The Washington Post. p. L10.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (November 3, 1967). "'Camelot' Opens at Cinerama Dome". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Gill, Brendan (November 4, 1967). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 168.

- ^ "Camelot". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 35 (408): 3. January 1968.

- ^ "Camelot (1967)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "The 40th Academy Awards | 1968". Oscars.org. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1968". Golden Globes. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Camelot (1967): Awards". IMDb. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "America's Greatest Music in the Movies" (PDF). AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs. American Film Institute. 2005. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bingen, Steven; Marc Wanamaker (2014). Warner Bros.: Hollywood's Ultimate Backlot. London: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-1-58979-962-2. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "A city commemorates its very own 'King Arthur'". Independent.ie. 2007-09-08. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

Bibliography[]

- Kennedy, Matthew (2014). Roadshow!: The Fall of Film Musicals in the 1960s. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199925674.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Camelot (film) |

- Camelot at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Camelot at IMDb

- Camelot at the TCM Movie Database

- Camelot at AllMovie

- Camelot at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1967 films

- English-language films

- American films

- 1960s romantic musical films

- 1960s musical comedy-drama films

- 1960s romantic comedy-drama films

- American musical comedy-drama films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- American romantic musical films

- Arthurian films

- Films based on musicals

- American films based on plays

- Films directed by Joshua Logan

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films scored by Alfred Newman

- Films scored by Ken Darby

- Films scored by Frederick Loewe

- Films set in England

- Films that won the Best Costume Design Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Alan Jay Lerner

- Warner Bros. films

- Films about royalty

- Films based on adaptations

- 1967 comedy films

- 1967 drama films

- Films set in castles