The Dirty Dozen

| The Dirty Dozen | |

|---|---|

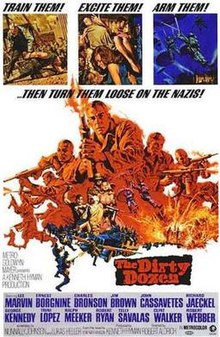

Theatrical release poster by Frank McCarthy | |

| Directed by | Robert Aldrich |

| Screenplay by | Nunnally Johnson Lukas Heller |

| Based on | The Dirty Dozen by E. M. Nathanson |

| Produced by | Kenneth Hyman |

| Starring | Lee Marvin Ernest Borgnine Charles Bronson Jim Brown John Cassavetes Richard Jaeckel George Kennedy Trini Lopez Ralph Meeker Robert Ryan Telly Savalas Clint Walker Robert Webber |

| Cinematography | Edward Scaife |

| Edited by | Michael Luciano |

| Music by | Frank De Vol |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 150 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Languages | English German French |

| Budget | $5.4 million[1] |

| Box office | $45.3 million[2] |

The Dirty Dozen is a 1967 war film starring Lee Marvin and featuring an ensemble supporting cast including Ernest Borgnine, Charles Bronson, Jim Brown, John Cassavetes, George Kennedy, Robert Ryan, Telly Savalas, Robert Webber and Donald Sutherland. The film, which was directed by Robert Aldrich,[3] was filmed in the UK at MGM-British Studios and released by MGM. It was a box office success and won the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing at the 40th Academy Awards in 1968. In 2001, the American Film Institute placed the film at number 65 on their 100 Years... 100 Thrills list.

The screenplay is based on the 1965 bestseller by E. M. Nathanson which was inspired by a real-life WWII unit of behind-the-lines demolition specialists from the 101st Airborne Division named the "Filthy Thirteen".[4][5]

Plot[]

In March 1944, OSS officer Major John Reisman is ordered by the commander of ADSEC in Britain, Major General Sam Worden, to undertake Project Amnesty, a top-secret mission to train some of the Army's worst prisoners and turn them into commandos to be sent on a virtual suicide mission just before D-Day. The target is a château near Rennes where dozens of high-ranking German officers will be eliminated in order to disrupt the chain of command of the Wehrmacht in Northern France before the Allied invasion. Reisman is told he can tell the prisoners that those who survive the mission will receive pardons for their crimes.

Reisman is assigned twelve convicts, all either serving lengthy sentences or destined for execution, including the slow-witted Vernon Pinkley; Robert Jefferson, an African American convicted of killing a man in a racial brawl; Samson Posey, a gentle giant who becomes enraged when pushed; Joseph Wladislaw, a taciturn coal miner with the ability to speak German; A. J. Maggott, a misogynist and religious fanatic; and Victor Franko, a former member of a Chicago organized-crime Syndicate with extreme problems with authority. Under the supervision of Reisman and military police Sergeant Clyde Bowren, the group begins training. After being forced to construct their own living quarters, the twelve are trained in combat by Reisman and gradually learn how to operate as a group. The men further bond after Franko leads a rebellion against orders to shave in cold water, resulting in Reisman rationing hot meals and soap, earning the men the nickname "The Dirty Dozen." Captain Stuart Kinder, a psychiatrist, evaluates the men and warns Reisman that they are all mentally unstable, with Maggott being the worst of the bunch.

For parachute training the men are sent to the base operated by Colonel Everett Breed. Under strict orders to keep their mission secret, Reisman's men run afoul of Breed and his troops, especially after Pinkley poses as a general and inspects Breed's troops. Angered at the usurpation of his authority, Breed attempts to discover Reisman's mission and attempts to get the program shut down by forcing two of his men to beat a confession out of Wladislaw, who is saved by Posey and Jefferson. The convicts blame Reisman for the attack, but realize the mistake after Breed and his men arrive at their base. Reisman infiltrates his own camp and gets the convicts to disarm Breed's paratroopers, forcing Breed to leave in humiliation.

After Reisman gets prostitutes for the men to celebrate the completion of their training, Worden and his chief of staff, Brigadier General James Denton, throw the book at him. Reisman's friend, Major Max Armbruster, suggests a test of whether Reisman's men are ready: during practice maneuvers which Breed will be taking part in, the "Dirty Dozen" will attempt to capture the Colonel's headquarters. During the maneuvers, the men use various unorthodox tactics, including theft, impersonation, and rule-breaking, to infiltrate Breed's headquarters and hold him and his men at gunpoint. Impressed, Worden approves Project Amnesty.

The men are flown to France. There is a slight snag when Pedro Jimenez, one of the Dozen, breaks his neck on the jump and dies, but the others proceed with the mission. Wladislaw and Reisman infiltrate the meeting disguised as German officers while the others set up in various locations in and around the chateau. The plan falls apart when Maggott sees a woman who had accompanied an officer, murders her and begins shooting, alerting the German officers, before Jefferson kills him. As the officers and their companions retreat to an underground bomb shelter, a firefight ensues between the Dozen and German reinforcements. Wladislaw and Reisman lock the Germans in the bomb shelter while the Dozen pry open the ventilation ducts to the shelter and drop unprimed grenades down, then pour gasoline inside. Jefferson throws primed grenades down each shaft and sprints for their vehicle, but is shot by a sniper before the grenades explode.

Reisman, Bowren and Wladislaw, the last remaining survivors of the assault team, make their escape. Back in England, a voiceover from Armbruster confirms that Worden exonerated the sole surviving member of the Dozen and communicated to the next of kin of the rest that "they lost their lives in the line of duty."

Cast[]

| Actor | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lee Marvin | Major John Reisman | |

| Ernest Borgnine | Major General Sam Worden | |

| Charles Bronson | Joseph Wladislaw | number 9: death by hanging |

| Jim Brown | Robert T. Jefferson | number 3: death by hanging |

| John Cassavetes | Victor R. Franko | number 11: death by hanging |

| Richard Jaeckel | Sergeant Clyde Bowren | |

| George Kennedy | Major Max Armbruster | |

| Trini Lopez | J. Pedro Jimenez | number 10: 20 years' hard labor |

| Ralph Meeker | Captain Stuart Kinder | |

| Robert Ryan | Colonel Everett Dasher Breed | |

| Telly Savalas | Archer J. Maggott | number 8: death by hanging |

| Donald Sutherland | Vernon L. Pinkley | number 2: 30 years' imprisonment |

| Clint Walker | Samson Posey | number 1: death by hanging |

| Robert Webber | Brigadier General James Denton | |

| Tom Busby | Milo Vladek | number 6: 30 years' hard labor |

| Ben Carruthers | S. Glenn Gilpin | number 4: 30 years' hard labor |

| Stuart Cooper | Roscoe Lever | number 5: 20 years' imprisonment |

| Robert Phillips | Corporal Carl Morgan | |

| Colin Maitland | Seth K. Sawyer | number 7: 20 years' hard labor |

| Al Mancini | Tassos R. Bravos | number 12: 20 years' hard labor |

Production[]

Writing[]

Although Robert Aldrich had failed to buy the rights to E.M. Nathanson's novel The Dirty Dozen while it was just an outline, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer succeeded in May 1963. On publication, the novel became a best-seller in 1965. It was adapted to the screen by veteran scriptwriter and producer Nunnally Johnson, and Lukas Heller. A repeated rhyme was written into the script where the twelve actors verbally recite the details of the attack in a rhyming chant to help them remember their roles while approaching the mission target:

- Down to the road block, we've just begun.

- The guards are through.

- The Major's men are on a spree.

- Major and Wladislaw go through the door.

- Pinkley stays out in the drive.

- The Major gives the rope a fix.

- Wladislaw throws the hook to heaven.

- Jimenez has got a date.

- The other guys go up the line.

- Sawyer and Gilpin are in the pen.

- Posey guards Points Five and Seven.

- Wladislaw and the Major go down to delve.

- Franko goes up without being seen.

- Zero Hour: Jimenez cuts the cable; Franko cuts the phone.

- Franko goes in where the others have been.

- We all come out like it's Halloween.

Casting[]

The cast included many World War II US veterans including Lee Marvin, Robert Webber and Robert Ryan (US Marine Corps); Telly Savalas and George Kennedy (US Army); Charles Bronson (US Army Air Forces); Ernest Borgnine (US Navy); and Clint Walker (US Merchant Marine).

John Wayne was the original choice for Reisman, but he turned down the role because he objected to the adultery present in the original script, which featured the character having a relationship with an Englishwoman whose husband was fighting on the Continent.[6] Jack Palance refused the "Archer Maggott" role when they would not rewrite the script to make his character lose his racism; Telly Savalas took the role instead.[7]

Six of the dozen were experienced American stars, while the "Back Six" were actors resident in the UK, Englishman Colin Maitland, Canadians Donald Sutherland and Tom Busby, and Americans Stuart Cooper, Al Mancini, and Ben Carruthers. According to commentary on The Dirty Dozen: 2-Disc Special Edition, when Trini Lopez left the film early, the death scene of Lopez's character where he blew himself up with the radio tower was given to Busby[8] (in the film, Ben Carruthers' character Glenn Gilpin is given the task of blowing up the radio tower while Busby's character Milo Vladek is shot in front of the château). Lopez's character dies off-camera during the parachute drop that begins the mission.[9] The impersonation of the general scene was to have been done by Clint Walker, but when he thought the scene was demeaning to his character, who was a Native American, Aldrich picked out Sutherland for the bit.[10][11]

Jim Brown, the Cleveland Browns running back, announced his retirement from American football at age 29 during the making of the film. The owner of the Browns, Art Modell, demanded Brown choose between football and acting. With Brown's considerable accomplishments in the sport (he was already the NFL's all-time leading rusher, was well ahead statistically of the second-leading rusher, and his team had won the 1964 NFL Championship), he chose acting. In Spike Lee's 2002 documentary Jim Brown: All-American Modell admitted he made a huge mistake in forcing Jim Brown to choose between football and Hollywood. He said that if he had it to do over again, he would never have made such a demand. Modell fined Jim Brown the equivalent of over $100 per day, a fine which Brown said that "today wouldn't even buy the doughnuts for a team".[12]

Filming[]

The production was filmed in UK in the summer of 1966.[13] Interiors and set pieces took place at MGM British Studios, Borehamwood where the château set was built under the direction of art director William Hutchinson. It was 720 yards (660 m) wide and 50 feet (15 m) high, surrounded with 5,400 square yards (4,500 m2) of heather, 400 ferns, 450 shrubs, 30 spruce trees and six weeping willows. Construction of the faux château proved problematic. The script required its explosion, but it was so solid that 70 tons of explosives would have been required for the effect. Instead, a cork and plastic section was destroyed.

Exteriors were shot throughout southeast England. The credit scenes at the American military prison – alluded in the movie to be Shepton Mallett – were shot in a courtyard at Ashridge House in Hertfordshire. Co-star Richard Jaeckel recalled that when the introductory lineup scene was first shot, Aldrich, who liked to play pranks on his actors, initially placed 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) Charles Bronson between 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) Clint Walker and 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) Donald Sutherland, which provoked an angry response from the diminutive Bronson, making Aldrich laugh.[14]

The jump school scene was at the former entrance to RAF Hendon in London. The wargame was filmed in and around the village of Aldbury. Bradenham Manor was the Wargames' Headquarters. Beechwood Park School in Markyate was also used as a location during the school's summer term, where the training camp and tower were built and shot in the grounds and the village itself as parts of "Devonshire". The main house was also used, appearing in the film as a military hospital.[15] After filming finished, the training camp huts were relocated and used as sports equipment storage for the school's playing fields. Residents of Chenies, Buckinghamshire complained to MGM when filming caused damage around their village.[13]

While making the film, some of the cast members gave an interview to ABC Film review, in which they contrasted their own real wartime ranks to their officer roles in the film:

George Kennedy: Took me two years to make Private First Class.

Lee Marvin: I didn't even make that in the Marines.

Ernest Borgnine: I was beneath notice in the Navy

For punks, we're doing all right, said Marvin. I wonder how the generals are doing?[16]

Heavy rains throughout the summer caused filming delays of several months, leading to $1 million in overruns and bringing the final cost to $5 million.[13] Principal photography wrapped at MGM-British Studios in September 1966 with post-production to be completed at MGM studios in Culver City, California.[13]

Release[]

Theatrical[]

The Dirty Dozen premiered at the Capitol Theatre in New York City on June 15, 1967[13] and opened at the 34th Street East theatre the following day.[17][18] Despite being shot in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the film was initially shown in 70 mm which cut off 15% of the film and resulted in a grainy look.[19]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The Dirty Dozen was a massive commercial success. In its first five days in New York, the film grossed $103,849 from 2 theatres.[18] Produced on a budget of $5.4 million, it earned theatrical rentals of $7.5 million in its first five weeks from 1,152 bookings and 625 prints, one of the fastest-grossing films at the time;[20] however, on Variety's weekly box office survey, based on a sample of key city theatres, it only reached number two at the U.S. box office behind You Only Live Twice until it finally reached number one in its sixth week.[21] It eventually earned rentals of $24.2 million in the United States and Canada from a gross of $45.3 million.[22] It was the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1967 and MGM's highest-grossing film of the year. It was also a hit in France, with admissions of 4,672,628.[23]

To coincide with its release, Dell Comics published a comic The Dirty Dozen in October 1967.[24][25]

Critical response[]

The film currently holds an 80% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 49 reviews.[26] On release, the film was criticised for its level of violence. Roger Ebert, who was in his first year as a film reviewer for the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote sarcastically:

I'm glad the Chicago Police Censor Board forgot about that part of the local censorship law where it says films shall not depict the burning of the human body. If you have to censor, stick to censoring sex, I say...but leave in the mutilation, leave in the sadism and by all means leave in the human beings burning to death. It's not obscene as long as they burn to death with their clothes on.[27]

In another contemporaneous review, Bosley Crowther called it "an astonishingly wanton war film" and a "studied indulgence of sadism that is morbid and disgusting beyond words"; he also noted:

It is not simply that this violent picture of an American military venture is based on a fictional supposition that is silly and irresponsible. ... But to have this bunch of felons a totally incorrigible lot, some of them psychopathic, and to try to make us believe that they would be committed by any American general to carry out an exceedingly important raid that a regular commando group could do with equal efficiency—and certainly with greater dependability—is downright preposterous.[17]

Crowther called some of the portrayals "bizarre and bold":

Marvin's taut, pugnacious playing of the major ... is tough and terrifying. John Cassavetes is wormy and noxious as a psychopath condemned to death, and Telly Savalas is swinish and maniacal as a religious fanatic and sex degenerate. Charles Bronson as an alienated murderer, Richard Jaeckel as a hard-boiled military policeman, and Jim Brown as a white-hating Negro stand out in the animalistic group.[17]

Art Murphy of Variety was more positive, calling it "an exciting World War II pre-D-Day drama" with an "excellent cast" and a "very good screenplay" with "a ring of authenticity to it".[19]

The Time Out Film Guide notes that over the years, "The Dirty Dozen has taken its place alongside that other commercial classic, The Magnificent Seven". The review then states:

The violence which liberal critics found so offensive has survived intact. Aldrich sets up dispensable characters with no past and no future, as Marvin reprieves a bunch of death row prisoners, forges them into a tough fighting unit, and leads them on a suicide mission into Nazi France. Apart from the values of team spirit, cudgeled by Marvin into his dropout group, Aldrich appears to be against everything: anti-military, anti-Establishment, anti-women, anti-religion, anti-culture, anti-life. Overriding such nihilism is the super-crudity of Aldrich's energy and his humour, sufficiently cynical to suggest that the whole thing is a game anyway, a spectacle that demands an audience.[28]

Accolades[]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[29] | Best Supporting Actor | John Cassavetes | Nominated |

| Best Film Editing | Michael Luciano | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio Sound Department | Nominated | |

| Best Sound Effects | John Poyner | Won | |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | Michael Luciano | Won |

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Robert Aldrich | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | John Cassavetes | Nominated |

| Laurel Awards | Top Action-Drama | Nominated | |

| Top Action Performance | Lee Marvin | Won | |

| Top Male Supporting Performance | Jim Brown | Nominated | |

| John Cassavetes | Nominated | ||

| Photoplay Awards | Gold Medal | Won | |

Year-end lists[]

Also, the film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – No. 65[30]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- The Dirty Dozen – Nominated Heroes[31]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[32]

Sequels, adaptations and remake[]

Three years after The Dirty Dozen was released, Too Late the Hero, a film also directed by Aldrich, was described as a "kind of sequel to The Dirty Dozen".[33] The 1969 Michael Caine film Play Dirty follows a similar theme of convicts recruited as soldiers. The 1977 Italian war film directed by Enzo G. Castellari, The Inglorious Bastards, is a loose remake of The Dirty Dozen.[34] Quentin Tarantino's 2009 Inglourious Basterds was derived from the English-language title of the Castellari film.[35][36]

Several TV films were produced in the mid-to-late 1980s which capitalized on the popularity of the first film. Lee Marvin, Richard Jaeckel and Ernest Borgnine reprised their roles for The Dirty Dozen: Next Mission in 1985, leading a group of military convicts in a mission to kill a German general who was plotting to assassinate Adolf Hitler.[37] In The Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission (1987), Telly Savalas, who had played the role of the psychotic Maggott in the original film, assumed the different role of Major Wright, an officer who leads a group of military convicts to extract a group of German scientists who are being forced to make a deadly nerve gas.[38] Ernest Borgnine again reprised his role of General Worden. The Dirty Dozen: The Fatal Mission (1988) depicts Savalas's Wright character and a group of renegade soldiers attempting to prevent a group of extreme German generals from starting a Fourth Reich, with Erik Estrada co-starring and Ernest Borgnine again playing the role of General Worden.[39] In 1988, Fox aired a short-lived television series starring Ben Murphy. Among the cast was John Slattery, who played Private Leeds in eight of the show's 11 episodes.[40]

The surviving cast members of the original film provided the voices of the toy soldiers in Joe Dante's Small Soldiers.

In 2014, Warner Bros. announced that director David Ayer would be the director of a live-action adaptation of the DC Comics property Suicide Squad, and Ayer has gone on to say that the film is "the Dirty Dozen with super villains", citing the original film as inspiration. In December 2019 Warner Brothers announced it was developing a remake with David Ayer set to direct.[41]

Historical authenticity[]

Nathanson states in the prologue to his novel The Dirty Dozen, that while he heard a legend that such a unit may have existed, he incorrectly heard they were convicts. He was unable to find any corroboration in the archives of the US Army in Europe. He instead turned his research of convicted felons into the subsequent novel. While he does not state from where he acquired the name, but Arch Whitehouse coined the name "Dirty Dozen" as the 12 enlisted men of the airborne section that would become the "Filthy Thirteen" after the lieutenant joined their ranks. In Arch Whitehouse's article in True Magazine, he claimed all the enlisted men were full-blood Indians, but in reality only their leader, Jake McNeice was quarter Choctaw. The parts of the Filthy Thirteen story that carried over into Nathanson's book were not bathing until the jump into Normandy, their disrespect for military authority, and the pre-invasion party. The Filthy Thirteen was in actuality a demolitions section with a mission to secure bridges over the Douve on D-Day.

A similarly named unit called the "Filthy Thirteen" was an airborne demolition unit documented in the eponymous book,[42] and this unit's exploits inspired the fictional account. Barbara Maloney, the daughter of John Agnew, a private in the Filthy Thirteen, told the American Valor Quarterly that her father felt that 30% of the film's content was historically correct, including a scene where officers are captured. Unlike the Dirty Dozen, the Filthy Thirteen were not convicts; however, they were men prone to drinking and fighting and often spent time in the stockade.[43][44]

Nathanson wrote the last chapter of the novel in the form of an epistolary novel, presenting the climactic battle at the chateau in the form of a written report.

See also[]

- List of American films of 1967

- Silmido, a 2003 Korean film about the true story to train convicts as black ops assassins in order to kill North Korean leader Kim Il Sung

References[]

- ^ Silver, Alain; Ursini, James (1995). Whatever Happened to Robert Aldrich?. Hal Leonard. p. 269. ISBN 978-0879101855. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Yardley, William (February 13, 2013). "Jake McNiece, Who Led Incorrigible D-Day Unit, Is Dead at 93". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "World War II soldier John (Jack) Agnew, whose unit inspired 'Dirty Dozen,' dies at 88". New York Daily News. Associated Press. April 12, 2010. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Randy; Olsen, James Stuart (1997). John Wayne: American. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press. p. 537.

- ^ "Actor Jack Palance Won't Play Racist for $141,000". Jet. XXIX (22): 59. March 10, 1966. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Commentary The Dirty Dozen: 2-Disc Special Edition

- ^ Film The Dirty Dozen: 2-Disc Special Edition

- ^ Patterson, John (September 3, 2005). "Total recall". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "These World War II Heroes Were Dirtier by the 'Dozen'". LA Times. May 19, 2000. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Cortes, Ryan (July 13, 2016). "Jim Brown retires while on the set of 'The Dirty Dozen'". The Undefeated. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The Dirty Dozen (1967)". www.catalog.afi.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Freese, Gene (2016). Richard Jaeckel, Hollywood's Man of Character. McFarland. p. 88. ISBN 9781476662107.

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen (1967) Filming Locations". www.themoviedistrict.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "WHAT LEE MARVIN REALLY THOUGHT OF THE DIRTY DOZEN". www.pointblankbook.com. June 16, 2017. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Crowther, Bosley (June 16, 1967). "The Dirty Dozen (1967)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "'Heat of Night' Scores With Crix; Quick B.O. Pace". Variety. August 9, 1967. p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murphy, A.D. (June 21, 1967). "Film Reviews: The Dirty Dozen". Variety. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "'Dirty Dozen' Nabs $7.5-Mil. In 5 Wks". Variety. August 9, 1967. p. 3.

- ^ "National Boxoffice Survey". Variety. August 9, 1967. p. 4.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1967". Variety. January 3, 1968. p. 25.

- ^ Soyer, Renaud (July 14, 2013) "Robert Aldrich Box Office" Archived May 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Story (in French).

- ^ Dell Movie Classic: The Dirty Dozen at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Dell Movie Classic: The Dirty Dozen at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 26, 1967). "The Dirty Dozen". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "The Dirty Dozen". Time Out. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "The 40th Academy Awards (1968) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Cinema: Jungle Rot". Time. June 8, 1970. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

War may be getting a bad name, but it still pays at the box office. Ask Director Robert Aldrich. His 1967 film The Dirty Dozen made millions by drafting a gang of incorrigible convicts into a mission behind enemy lines. Too Late the Hero is a kind of sequel to The Dirty Dozen, based once again on a World War II suicide mission.

- ^ "Inglourious Basterds Has Inglorious Beginnings". FlickDirect. August 13, 209. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Inglourious Basterds Review". CBC News. August 21, 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Wise, Damon (August 15, 2009). "Inglourious Basterds Guide". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ The Dirty Dozen: Next Mission at IMDb[unreliable source?]

- ^ The Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ The Dirty Dozen: The Fatal Mission at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ Dirty Dozen: The Series at IMDb[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Dirty Dozen Movie Remake Recruits Suicide Squad Director David Ayer". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Killblane, Richard; McNiece, Jake (May 19, 2003). The Filthy Thirteen: From the Dustbowl to Hitler's Eagle's Nest: The True Story of the 101st Airborne's Most Legendary Squad of Combat Paratroopers. Casemate. ISBN 978-1935149811. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Associated Press, April 11, 2010". Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ The Filthy Thirteen: The U.S. Army's Real "Dirty Dozen" American Valor Quarterly. Winter 2008-09. Retrieved April 10, 2010. Archived April 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Dirty Dozen |

- The Dirty Dozen at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Dirty Dozen at IMDb

- The Dirty Dozen at AllMovie

- The Dirty Dozen at the TCM Movie Database

- Operation Dirty Dozen, a behind-the-scenes featurette following Lee Marvin and the film's cast during their time in England

- 1967 films

- 1960s action adventure films

- 1960s action war films

- British action war films

- American films

- American action adventure films

- American action war films

- English-language films

- Films about capital punishment

- Films about the United States Army

- Films adapted into comics

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Robert Aldrich

- Films scored by Frank De Vol

- Films set in 1944

- Films set in France

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Nunnally Johnson

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- War adventure films

- Western Front of World War II films

- Photoplay Awards film of the year winners

- American World War II films

- British World War II films