The Hideous Sun Demon

| The Hideous Sun Demon | |

|---|---|

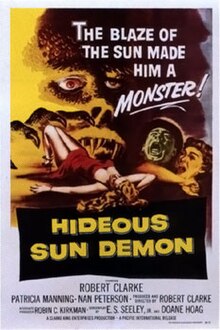

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Robert Clarke |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Tom Boutross |

| Music by | John Seely |

| Distributed by | Pacific International Enterprises |

Release date |

|

Running time | 74 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50,000 |

The Hideous Sun Demon (sometimes billed as The Sun Demon, or in the UK as Blood on His Lips) is a 1958 science fiction horror film written, directed, and produced by Robert Clarke, who also starred in the film. It also stars Patricia Manning, Nan Peterson, Patrick Whyte, and Fred La Porta. The film focuses on a scientist (portrayed by Clarke) who is exposed to a radioactive isotope and soon finds out that it comes with horrifying consequences.

The film was inspired by the financial success of The Astounding She-Monster in which Clarke had starred. The film's crew was made up of University of Southern California film students, and the film's cast were either unknowns or Clarke's family and friends. The film was shot during 12 consecutive weekends and was shot by three different cinematographers. Originally budgeted at $10,000, it ended up costing $50,000. The Hideous Sun Demon premiered on August 29, 1958 as part of a double bill with Roger Corman's Attack of the Crab Monsters. The film received mostly negative reviews upon its release, but has since become a cult film and has been referenced and parodied many times. An unauthorized sequel, the 1965 short film Wrath of the Sun Demon, was produced by Donald F. Glut. Two redubbed versions of the original film have been released: the comedic Hideous Sun Demon: Special Edition and What's Up, Hideous Sun Demon (also known as Revenge of the Sun Demon), the latter of which was produced with Clarke's permission.

Plot[]

When research scientist Dr. Gilbert "Gil" McKenna (Clarke) falls unconscious after accidentally being exposed to radiation during an experiment with a new radioactive isotope, he is rushed to a nearby hospital. Attending physician Dr. Stern (Robert Garry) is surprised to find that Gil shows no signs of burns typical for five-minute exposure to radiation and informs Gil's co-workers, lab assistant Ann Russell (Patricia Manning) and scientist Dr. Frederick Buckell (Patrick Whyte), that he will keep the patient under observation for several days.

Later, Gil is taken to a solarium to receive the sun's healing rays. While he naps, he transforms into a reptilian creature, horrifying the other patients. Fleeing from the scene, Gil discovers his new appearance. Stern notifies Ann and Dr. Buckell about the incident, theorizing that the exposure to radiation caused a reversal of evolution, transforming Gil into a prehistoric reptile after exposure to sunlight. Stern suggests that Gil can control his symptoms by staying in the dark and remaining in the hospital, but admits that the patient cannot be held against his will.

Having reverted to normal, a disconsolate Gil notifies Ann of his resignation. Confining himself to his house and only coming out at night, Gil spends his hours drinking and wandering aimlessly around the grounds of his estate. He later drives to a bar where sultry piano player Trudy Osborne (Nan Peterson) is performing.

Buckell soon receives word that noted radiation-poisoning specialist Dr. Jacob Hoffman (Fred La Porta) has agreed to help Gil and plans on arriving in the area within a few days. When radiation poisoning studies offer no leads on solving Gil's own particular symptoms, the distraught scientist contemplates suicide, but soon changes his mind. Instead, Gil returns to the bar where Trudy joins him for a drink and comments that the evening is not over because it is "never late until the sun comes up." Although Gil is disturbed by the comment, his loneliness draws him closer to her. When bar patron George insinuates that he has purchased Trudy's company for the evening, Gil defends her, causing a fight between the two men. After knocking George unconscious, Gil flees with Trudy into the night. Later that evening, after walking the shoreline, they make love, falling asleep in the sand until the morning light awakens Gil. Horrified, Gil flees in his car leaving Trudy stranded on the beach. Arriving at the house, Gil runs in, but not before the transformation occurs.

Ann soon arrives, discovering Gil cowering in the cellar in a state of shock. Believing that he is beyond help, Gil at first refuses to see Dr. Hoffman, but after Ann's tearful pleading, Gil reluctantly agrees. During the examination, Dr. Hoffman orders Gil to remain in the house at all times as a precaution until he can return with help. Feeling guilty for leaving Trudy, Gil returns to the bar but is brutally beaten by George and his gang. Gil regains consciousness the next morning and discovers that Trudy, having felt sorry for him, brought him home to her apartment. George soon arrives and, upon seeing Gil, forces him at gunpoint out into the daylight. Transforming into the creature, Gil murders George in front of the horrified Trudy before fleeing into the hills. Returning to the house, Gil finds Ann, Dr. Hoffman and Buckell waiting there and returns to his normal human state. A disturbed Gil later admits to the murder, with the others assuring him that he acted in self-defense, but when the police arrive with an arrest warrant, the hysterical Gil flees from the grounds in his car and accidentally hits a police officer.

Hiding inside an oil field shack while police comb the area and set up roadblocks, Gil is discovered by young Suzy who offers to fetch him cookies. Hurrying back to her house, Suzy is caught hoarding cookies by her mother and is forced to reveal who they are for. While her mother calls the police, Suzy slips out of the door to return to Gil. Her mother chases after her into the oil field, and police cars soon arrive. Realizing Suzy is endangered by being with him, Gil carries the girl out of the shack into the sunlight where he lets her go. He soon transforms into the creature. In the ensuing police chase, Gil slaughters one of the officers and then climbs the stairs to the top of a tall natural gas tank, where the remaining officer chases after him. As Gil begins to strangle him, the officer shoots Gil in the neck. Mortally wounded, the mutated Gil falls several stories to his death while Buckell, Hoffman and a sobbing Ann watch in dismay.

Cast[]

- Robert Clarke as Dr. Gilbert McKenna / The Sun Demon

- Patricia Manning as Ann Russell

- Nan Peterson as Trudy Osborne

- Patrick Whyte as Dr. Frederick Buckell

- Fred La Porta as Dr. Jacon Hoffman

- Peter Similuk as George Messorio

- Bill Hampton as Police Lt. Peterson

- Robert Garry as Dr. Stern

- Donna King as Suzy's Mother

- Xandra Conkling as Suzy

- Del Courtney as Radio DJ

Production[]

Development[]

Development for The Hideous Sun Demon began after the 1957 release of The Astounding She-Monster, a science fiction film starring Clarke. In his contract for the film, Clarke was promised five percent of She-Monster's profits in addition to his salary. Although Clarke later admitted that the film was awful, it was a financial success, with Clarke receiving a sizable sum from the film's box office returns.[1][2] Inspired by that film's financial success, Clarke decided to direct his own low-budget science fiction film.[2] According to Clarke, the story for the film was inspired by Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which dealt with multiple personalities.[2] Clarke and co-writer/director Tom Boutross wrote the first draft of the screenplay (although some sources, including Clarke himself, say his friend Phil Hiner co-wrote the first draft[1]), then-titled Saurus or Sauros, names taken from the Latin word meaning "reptile".[1][2][3][4] Other working titles for the film included Strange Pursuit and Terror in the Sun. Boutross, who is also credited as one of the film's co-directors, later edited films like Rat Fink (1965), A Man Called Dagger (1967) and 1974 hit The Legend of Boggy Creek.[5] The first draft of the script was significantly different from what would be shown in the finished film. The original storyline centered on an explorer and a female lawyer searching for uranium in the country of Guatemala. While there, they are tormented by a man who had been mutated by experiments conducted on him by his scientist father, who is an expert in radiation, and when the young man is exposed to the sun, he transforms into a reptilian creature.[1]

The film's crew consisted of students from the University of Southern California. Clarke pitched the story idea to Robin Kirkman, a student at USC, who liked the idea. The two men formed the production company Clarke-King Enterprises, and Kirkman worked as the film's associate producer.[1] E.S. Seely, who later directed the 1961 film Shangri-La, wrote the final draft of the film's screenplay,[5] which was then rewritten by Doane R. Hoag who "polished the dialogue", according to Clarke.[6][7] The film was initially budgeted at $10,000, but by the end of production, it had cost $50,000 in total.[1][8][9][10][11] The film was Clarke's first and only effort as writer or director.[4]

Casting[]

Clarke, the film's director, writer and producer, also starred in the lead role of Dr. Gilbert McKenna. A veteran actor, he wanted his character to seem realistic and multi-dimensional, with both bad and good qualities.[12] "I acted the part as if I wouldn't let anything get in my way", Clarke later recalled.[5] The rest of the cast consisted mostly of aspiring actors and actresses from around USC, with some characters played by Clarke's friends and family.[10][1] Actress Nan Peterson, in her acting debut, was cast in the role of Trudy Osborne because of her voluptuous figure, according to Clarke.[8] Originally, singer Marilyn King of The King Sisters, who was Clarke's sister-in-law, was cast for the role, but she dropped out due to her pregnancy at the time of production. King, however, did write and perform the song "Strange Pursuit", featured in the bar scene in the film, providing the vocals for Peterson's character.[1][13] Peterson had previously worked as a model for Catalina Bathing Suits and was touring nationwide as "Miss Vornado" for the Vornado air conditioning company.[14] Xandra Conkling, who played the little girl who befriends McKenna in the film, was actually the daughter of Clarke's wife's sister. Pearl Driggs, who portrayed an old woman on the hospital roof, was Clarke's mother-in-law.[13][15] A radio announcer heard in the film was played by Clarke's sister-in-law's fiancé, and Clarke's nephew played a newsboy in the film.[1]

Filming[]

Principal photography for The Hideous Sun Demon commenced in 1957,[16] lasting over a period 12 consecutive weekends on rented equipment.[1][17][12] At the time of production, Clarke was busy acting in other films during weekdays while the student film crew attended school. A decision to film during the weekends was made, since it was the only time that both Clarke and the crew were free.[1] The cast and crew were paid $25 per day. Due to the film's low budget, items such as clothing and make-up were provided by the film's stars themselves. "I had to do my own make-up, [and] use my own clothes ... it was a very low-budget film", Peterson later recalled.[14] The film was shot by three different cinematographers, all credited at the end of the film: John Morrill, who Clarke later stated shot at least half the film; Vilis Lapeniks, who also shot Eegah and the 1966 horror film Queen of Blood before working on bigger projects like Newman's Law (1974), Capone (1975) and Kiss Daddy Goodbye (1981); and Stan Follis, in his only film credit.[5]

The film was one of the first to use practical locations during shooting. According to Clarke, "When we needed a scene in a bar, we went to Santa Monica and asked a guy how much money he would charge to let us come in and shoot scenes in his bar".[17][12] Because Clarke also acted in the film, editor and co-writer Tom Boutross served as co-director on the film.[17][12] The main character's home in the film was located on Lafayette Boulevard in Los Angeles, which is no longer standing. The four-story rooming house was rented for 5–6 weekend days for $25 per day. The exterior shots of the character's house were shot in a different location around Glendale Hill.[17][12] A scene in the film where a transformed McKenna graphically crushes a rat with his bare hands was not in the script, and was improvised while on location. The effect was accomplished by placing ketchup on the rat; Clarke would then gently squeeze the rat, making the ketchup ooze from his fingers.[18][19][20] This scene was removed from prints that were released on television, but was later restored.[5] Coastal scenes were filmed at Bass Rock and near Trancas, while other scenes were filmed near Signal Hill. The film's climax was filmed around the area of the Union Station train depot.[12] The large gas tank, which stood over 300 feet tall, was made available to the cast and crew by the Southern California Gas Company. Filming at this location proved to be a challenge, as the cast and crew had trouble communicating with each other, with Clarke attempting to direct the film crew while on top of the large structure.[8][10]

The title monster was designed by production designer Richard Cassarino,[Note 1] who created the suit for $500, and was built over a diver's wetsuit. Conditions inside the suit were very hot; combined with the humid weather, this caused Clarke, who performed his own stunts in the film, to sweat profusely.[15][22] The original mask is currently owned by archivist and occasional actor Bob Burns.[23] Cassarino later worked as production designer for the 1958 film Hell Squad, and also was responsible for designing the sea creature costume in the science fiction film Destination Inner Space (1966).[5]

Release[]

Theatrical release[]

Clarke initially had no distribution deals set up for the film. Clarke's brother – a sales manager at an Amarillo, Texas, television station – put him into contact with the owner of several local drive-in theaters. Clarke agreed to premiere his film in Amarillo, and it played on a double bill with the Roger Corman film Attack of the Crab Monsters, under the alternate title The Sun Demon, on August 29, 1958. Peterson and Clarke appeared at the premiere, and, after the film, performed an interview together. While the audience was distracted, Clarke changed into his costume and made an appearance as the Sun Demon.[24] After this success, Clarke declined a distribution deal with American International Pictures and instead chose a competitor, Miller-Consolidated Pictures, who distributed it across the US and UK in December 1959. Clarke made additional personal appearances as the Sun Demon. However, 18 months after the company started distributing the film, it went bankrupt. Because of this, Clarke never saw any income from the deal.[1][25] Clarke later sold off the films rights to various distributors.[1] In the United Kingdom, the film was distributed by D.U.K. and released with the title Blood on His Lips.[26][27]

Home media release[]

The Hideous Sun Demon was released on VHS as a part of Elvira's Movie Macabre by Rhino Home Video on September 8, 1993.[28] It was later released by First Look Home Entertainment on September 18, 1997.[29] The film made its debut on DVD on March 21, 2000, issued by Image Entertainment.[30] It was later re-released by Image Entertainment as a two-disc double feature on December 30, 2003, paired with a comically redubbed sequel titled What's Up, Hideous Sun Demon or Revenge of the Sun Demon. This version of the film was later released on DVD by Image Entertainment on July 15, 2003.[31]

Reception[]

Critical reception for The Hideous Sun Demon has been mostly negative. In a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin gave the film a negative review, saying that "wordy dialogue, poor acting, uneven photography and sub-standard sound all add to the disadvantage of a hopelessly illogical plot".[26]

Bob Stephens of the San Francisco Chronicle, in a 2000 review, criticized the film's narrative slightness and Peter Similuk's casting, but also wrote that he "must confess that I enjoy Demon. Its naivete is a more reliable pathway to wonder than the cynicism and condescension of contemporary fantasy films could ever be".[32] TV Guide gave the film a negative review, awarding it 1.5 out of 4 stars and calling it "laughable", but also commented that the monster costume was good.[33] Leonard Maltin gave the film a negative review, criticised the film's production values, calling it "hideous".[34]

In his book The Encyclopedia of Monsters, author Jeff Rovin called it "a clever twist on the Wolfman theme" and an "effective and gritty film [that] boasts an excellent monster costume".[35] Allmovie gave the film a positive review, calling it "a staple of TV horror programming since the early 1960s" and praising the film's claustrophobic feel, editing and actor/director Clarke's performance as the lead character, while criticizing the film's stock characters and "clunky" dialogue.[11] In Cult Horror Films, Welch D. Everman wrote that the film expresses traditional 1950s themes: a warning about the dangers of nonconformity and a mixed message about nuclear energy.[36] Chris Barsanti wrote in The Sci-Fi Movie Guide that the film distinguishes itself from other 1950s radioactive monster films by being an allegory for alcoholism.[37] The film has developed a cult following over the years since its release.[4]

The full story of the making of the movie (complete with interviews with some of the participants) plus the script and pressbook are featured in the book "Scripts from the Crypt: 'The Hideous Sun Demon'" (BearManor, 2015) by Tom Weaver.

Legacy[]

"To think that we made Sun Demon with a crew that were students, and that the picture eventually became a commercial success—that really is a great achievement. To me it's quite remarkable!"

Robert Clarke on the film's lasting impact[38]

Wrath of the Sun Demon[]

In 1965, seven years after the release of the original film, a student short film serving as an unauthorized sequel was made by amateur filmmaker Don Glut, after he discovered the Sun Demon mask in Bob Burns' collection.[23] Filmed in black and white with a running time of three-and-a-half minutes, Wrath of the Sun Demon starred Burns as the Sun Demon. The short film was made with the support of the University of Southern California, where Glut was a student at the time. The plot centered on a man (presumably McKenna) transforming into the Sun Demon and terrorizing several people before falling to his death off a cliff. The film also starred John Schuyler as the film's hero and Burns' wife Kathy.[23]

Burns and his wife had been friends with Schuyler before production of the film. According to Glut, Schuyler had recently purchased a new sports jacket and did not want it to get soiled or damaged during production. During the fight scene, in order to avoid stepping on and damaging it, Schuyler would remove the jacket and carry it over his shoulder. When the time came for the film's climax, where the Sun Demon fell to his death off a cliff, neither Burns nor Glut wanted to do the stunt, and neither wanted to damage the mask by putting it on a dummy. So Burns modified a G.I. Joe action figure so that it resembled the Sun Demon, and Glut then shot the figure in slow motion tumbling down a hole that resembled a valley. The original film's soundtrack was later added to the remake during post-production, with Glut's friend Bart Andrews supplying the Sun Demon's voice.[39]

Parodies[]

Two redubbed versions of the film have been released. Years after Clarke sold off the film's rights, they were purchased from Wade Williams by Hadi John Salem and Gregory Steven Brown, who released a redubbed version of the film titled Hideous Sun Demon: The Special Edition.[23] Unlike the original film, this version was intended to be a comedy.[40]

Writing for Cinefantastique, David J. Hogan described plans for the original footage to be redubbed using a new screenplay written by Mark and Allan Estrin, with Clarke's character Gil renamed Ishmael Pivnik. This version was to center on Pivnik, whose formula for an oral suntan lotion transforms the hapless scientist into a monster.[23] Salem and Brown were inspired by Woody Allen's redubbing of the 1965 Japanese spy thriller film Kokusai himitsu keisatsu: Kagi no kagi, which Allen then transformed into his directorial debut comedy film, What's Up, Tiger Lily?.[41][42][43] The resulting redubbing was titled What's Up, Hideous Sun Demon[44] (also known as Revenge of the Sun Demon), which was released with the original director's permission. Salem and Brown were not credited as the producers in this version, which was produced by Jeffrey A. Montgomery and written by Craig Mitchell. New footage for this version was shot with Clarke's son Cam along with Googy Gress, Mark Holton and Susan Tyrell.[40] Actor and talk show host Jay Leno provided the uncredited voice for McKenna.[45]

Image Entertainment released this film on DVD twice in 2003, first by itself on July 15, and later as a double feature with The Hideous Sun Demon on December 30.[46]

In other media[]

Clips from The Hideous Sun Demon appeared in the film It Came from Hollywood,[47] while part of the film's soundtrack was used during the cemetery chase scene in Night of the Living Dead.[48] The film appeared on Elvira's Movie Macabre, a television series in which the title character comments on the films that are shown,[49] and the screenplay for the film was published as Scripts from the Crypt: The Hideous Sun Demon by BearManor on May 1, 2011.[50][51] A modeling kit of the Sun Demon character was released by Resin from the Grave in 1988, sculpted by Fred Hinck.[52]

In an interview with UK publishing company PS Publishing, author Bruce Golden credited The Hideous Sun Demon as inspiration for his book Monster Town. According to Golden, he previously wrote a short story titled, "I Was a Teenage Hideous Sun Demon", which he described as a "dark satire" of the film.[53] The band Hideous Sun Demons was named after the film.[54] It was also spoofed by RiffTrax on March 20, 2015.[55]

Notes[]

References[]

Bibliography

- "Catalog - The Hideous Sun Demon". AFI.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Barsanti, Chris (22 September 2014). The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: The Universe of Film from Alien to Zardoz. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-533-4.

- Bogue, Mike (20 July 2017). Apocalypse Then: American and Japanese Atomic Cinema, 1951-1967. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6841-3.

- Glut, Don (30 May 2007). I Was a Teenage Movie Maker: The Book. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3041-3.

- Johnson, John (1996). Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0093-5.

- Okuda, Ted; Yurkiw, Mark (9 February 2016). Chicago TV Horror Movie Shows: From Shock Theatre to Svengoolie. SIU Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-3538-1.

- Rhodes, Gary (2003). Horror at the Drive-in: Essays in Popular Americana. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1342-3.

- Warren, Bill (19 October 2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4230-0.

- Weaver, Tom (27 September 2006). Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers: Writers, Producers, Directors, Actors, Moguls and Makeup. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2858-8.

- Weaver, Tom (2000). Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes: The Mutant Melding of Two Volumes of Classic Interviews. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0755-2.

- Weaver, Tom (27 October 2004). Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Flashbacks: Conversations with 24 Actors, Writers, Producers and Directors from the Golden Age. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2070-4.

- Weaver, Tom (10 January 2014). A Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde: Interviews with 62 Filmmakers. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5831-8.

- Weiner, Robert; Barba, Shelley (10 January 2014). In the Peanut Gallery with Mystery Science Theater 3000: Essays on Film, Fandom, Technology and the Culture of Riffing. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8572-7.

Citations[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Warren 2009, p. 365.

- ^ a b c d Weaver 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Weaver 2000, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Deming, Mark. "The Hideous Sun Demon (1959) - Thomas Bontross, Gianbatista Cassarino, Robert Clarke". Allovie.com. Mark Deming. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Warren 2009, p. 366.

- ^ Weaver 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Weaver 2006, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Weaver 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Weaver 2004, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Weaver 2006, p. 85.

- ^ a b Eder, Bruce. "The Hideous Sun Demon (1959) - Thomas Bontross, Gianbatista Cassarino, Robert Clarke". Allmovie.com. Bruce Eder. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Weaver 2006, p. 84.

- ^ a b Weaver 2000, p. 86.

- ^ a b Weaver 2014, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Weaver 2006, p. 86.

- ^ AFI 2019.

- ^ a b c d Weaver 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Johnson 1996, p. 196.

- ^ Weaver 2000, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Weaver 2006, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Bogue 2017, p. 63.

- ^ Johnson 1996, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e Warren 2009, p. 367.

- ^ Weaver 2014, p. 215.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 56.

- ^ a b "Blood On His Lips". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 28 no. 324. London: British Film Institute. 1961. p. 80.

- ^ Warren 2009, p. 364.

- ^ Amazon.com: Elvira: Hideous Sun Demon [VHS]: Robert Clarke, Patricia Manning, Nan Peterson, Patrick Whyte, Fred La Porta, Peter Similuk, William White, Robert Garry, Donna King, Xandra Conkling, Del Courtney, Richard Cassarino, Tom Boutross, Robin C. Kirkman, Doane R. Hoag, E.S. Seeley Jr., Phil Hin. ASIN 6301773403.

- ^ Amazon.com: The Hideous Sun Demon [VHS]: Robert Clarke, Patricia Manning, Nan Peterson, Patrick Whyte, Fred La Porta, Peter Similuk, William White, Robert Garry, Donna King, Xandra Conkling, Del Courtney, Richard Cassarino, Tom Boutross, Robin C. Kirkman, Doane R. Hoag, E.S. Seeley Jr., Phil Hiner. ASIN 6304680465.

- ^ Amazon.com: The Hideous Sun Demon: Robert Clarke, Patricia Manning, Nan Peterson, Patrick Whyte, Fred La Porta, Peter Similuk, William White, Robert Garry, Donna King, Xandra Conkling, Del Courtney, Richard Cassarino, Tom Boutross, Robin C. Kirkman, Doane R. Hoag, E.S. Seeley Jr., Phil Hiner: Movies & TV. ASIN 6305772711.

- ^ "Amazon.com: Revenge of the Sun Demon: Bernard Behrens, Zachary Berger, Bill Capizzi, Cam Clarke, Robert Clarke, Del Courtney, Pearl Driggs, Paul Frees, Robert Garry, Barbara Goodson, Googy Gress, Mark Holton, John Lambert, Steve Dubin, Craig Mitchell, Glenn Morgan, Jeffrey A. Montgomery, Kevin Kelly Brown: Movies & TV". Amazon.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Stephens, Bob (March 25, 2000). "1950s sci-fi Demon men, devil girls". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Hideous Sun Demon Review". TV Guide.com. TV Guide. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. Penguin Press. p. 618. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- ^ Rovin, Jeff (1989). The Encyclopedia of Monsters. Facts on File. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-8160-1824-6.

- ^ Everman, Welch D. (1993). Cult Horror Films: From Attack of the 50 Foot Woman to Zombies of Mora Tau. Citadel Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8065-1425-3.

- ^ Barsanti, Chris (2014). The Sci-Fi Movie Guide. Visible Ink Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-57859-533-4.

- ^ Weaver 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Glut 2007, p. 158.

- ^ a b Warren 2009, p. 368.

- ^ Warren 2009, pp. 367–368.

- ^ Mike White (28 March 2014). "Say What? A Brief History of Mock Dubbing". Cashiers du Cinemart. Vol. 18. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Mavis, Paul. "What's Up, Tiger Lily?". DVD Talk. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ^ Weiner & Barba 2014, p. 104.

- ^ Okuda & Yurkiw 2016, p. 157.

- ^ "Revenge of the Sun Demon (1983) -". Allmovie.com. AllMovie. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (June 16, 2005). "Robert I. Clarke, 85; Familiar Face from Monster Movies and Myriad TV Shows". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ Sumiko Higashi (1991). "Night of the Living Dead: A Horror Film about the Horrors of the Vietnam Era". In Linda Dittmar; Gene Michaud (eds.). From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Rutgers University Press.

- ^ Cobb, Mark Hughes (October 22, 1990). "Bewitching Halloween Alternatives". The Tuscaloosa News.

- ^ Tom Weaver (1 May 2011). Scripts from the Crypt: The Hideous Sun Demon. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-700-3.

- ^ Weaver, Tom (May 2011). Scripts from the Crypt: The Hideous Sun Demon (Volume 1): Tom Weaver: 9781593937003: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-1593937003.

- ^ Mark C. Glassy (28 November 2012). Movie Monsters in Scale: A Modeler's Gallery of Science Fiction and Horror Figures and Dioramas. McFarland. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-7864-6884-3.

- ^ "Interview: MONSTER TOWN by Bruce Golden". PS Publishing.co.uk. PS Publishing. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "MAGNA CARTA RECORDS > Releases > THE HIDEOUS SUN DEMONS - The Hideous Sun Demons". Magna Carta.net. Magna Carta Records. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ RiffTrax

Further reading[]

- Various Authors (March 2014). Cashiers du Cinemart 18. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-304-90869-8.

- Allen A. Debus (14 July 2016). Dinosaurs Ever Evolving: The Changing Face of Prehistoric Animals in Popular Culture. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2432-7.

- Christopher M. O’Brien (31 August 2012). The Forrest J Ackerman Oeuvre: A Comprehensive Catalog of the Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Screenplays, Film Appearances, Speeches and Other Works, with a Concise Biography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9230-5.

- Jan Stacy; Ryder Syvertsen (1983). The Great Book of Movie Monsters. Contemporary Books. ISBN 978-0-8092-5525-2.

- James Robert Parish; Michael R. Pitts (1977). The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1029-7.

- Leslie Halliwell (1 December 1994). Halliwell's film guide. HarperPerennial. ISBN 9780062715890.

- Grobaty, Tim (20 November 2012). Location Filming in Long Beach. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-61423-775-4.

- Greg Kowalski (18 July 2002). Hamtramck: The Driven City. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-1395-5.

- Michael R. Pitts (January 2002). Horror Film Stars. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1052-1.

- Will Viharo (1 May 2011). I Lost My Heart in Hollywood/Diary of a Dick. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-257-62354-9. (p69)

- Stephen Jones (1 March 2012). The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 16. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-78033-713-5.

- Christopher Golden; Stephen R. Bissette; Thomas E. Sniegoski (August 2000). The Monster Book. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-04259-2.

- Phil Hardy (1 October 1995). The Overlook film encyclopedia: Science fiction. Overlook Press. ISBN 978-0-87951-626-0.

- Michael Weldon (1996). The Psychotronic Video Guide To Film. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-13149-4.

- Tim Wynne-Jones (26 October 2010). Rex Zero, The Great Pretender. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR). ISBN 978-1-4299-8928-2. (p30)

- Alan G. Frank (1 January 1982). The Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Handbook. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-389-20319-3.

- Tom Weaver (May 2011). Scripts from the Crypt: The Hideous Sun Demon. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-700-3.

- Bonnie Noonan (18 May 2005). Women Scientists in Fifties Science Fiction Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2130-5.

- Pat Kirkham; Janet Thumim (1993). You Tarzan: Masculinity, Movies and Men. Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 978-0-85315-778-6.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Hideous Sun Demon |

- The Hideous Sun Demon at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Hideous Sun Demon at AllMovie

- The Hideous Sun Demon at IMDb

- The Hideous Sun Demon at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Hideous Sun Demon at the TCM Movie Database

Wrath of the Sun Demon

What's Up, Hideous Sun Demon?/Revenge of the Sun Demon

- 1958 films

- English-language films

- 1958 horror films

- 1950s science fiction horror films

- American films

- American independent films

- American science fiction horror films

- American monster movies

- 1950s monster movies

- American black-and-white films

- Films about lizards

- Films shot in California